Escholarship California Italian Studies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Casting Call: Spatial Impressions in the Work of Rachel Whiteread

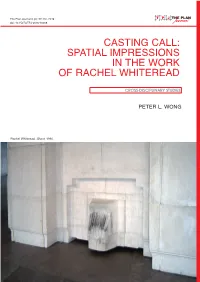

The Plan Journal 0 (0): 97-110, 2016 doi: 10.15274/TPJ-2016-10008 CASTING CALL: SPATIAL IMPRESSIONS IN THE WORK OF RACHEL WHITEREAD CROSS-DISCIPLINARY STUDIES PETER L. WONG Rachel Whiteread, Ghost, 1990. Casting Call: Spatial Impressions in the Work of Rachel Whiteread Peter L. Wong ABSTRACT - For more than 20 years, Rachel Whiteread has situated her sculpture inside the realm of architecture. Her constructions elicit a connection between: things and space, matter and memory, assemblage and wholeness by drawing us toward a reciprocal relationship between objects and their settings. Her chosen means of casting solids from “ready- made” objects reflect a process of visual estrangement that is dependent on the original artifact. The space beneath a table, the volume of a water tank, or the hollow undersides of a porcelain sink serve as examples of a technique that aligns objet-trouvé with a reverence for the everyday. The products of this method, now rendered as space, acquire their own autonomous presence as the formwork of things is replaced by space as it solidifies and congeals. The effect is both reliant and independent, familiar yet strange. Much of the writing about Whiteread’s work occurs in the form of art criticism and exhibition reviews. Her work is frequently under scrutiny, fueled by the popular press and those holding strict values and expectations of public art. Little is mentioned of the architectural relevance of her process, though her more controversial pieces are derived from buildings themselves – e,g, the casting of surfaces (Floor, 1995), rooms (Ghost, 1990 and The Nameless Library, 2000), or entire buildings (House, 1993). -

The Influence of International Town Planning Ideas Upon Marcello Piacentini’S Work

Bauhaus-Institut für Geschichte und Theorie der Architektur und Planung Symposium ‟Urban Design and Dictatorship in the 20th century: Italy, Portugal, the Soviet Union, Spain and Germany. History and Historiography” Weimar, November 21-22, 2013 ___________________________________________________________________________ About the Internationality of Urbanism: The Influence of International Town Planning Ideas upon Marcello Piacentini’s Work Christine Beese Kunsthistorisches Institut – Freie Universität Berlin – Germany [email protected] Last version: May 13, 2015 Keywords: town planning, civic design, civic center, city extension, regional planning, Italy, Rome, Fascism, Marcello Piacentini, Gustavo Giovannoni, school of architecture, Joseph Stübben Abstract Architecture and urbanism generated under dictatorship are often understood as a materialization of political thoughts. We are therefore tempted to believe the nationalist rhetoric that accompanied many urban projects of the early 20th century. Taking the example of Marcello Piacentini, the most successful architect in Italy during the dictatorship of Mussolini, the article traces how international trends in civic design and urban planning affected the architect’s work. The article aims to show that architectural and urban form cannot be taken as genuinely national – whether or not it may be called “Italian” or “fascist”. Concepts and forms underwent a versatile transformation in history, were adapted to specific needs and changed their meaning according to the new context. The challenge is to understand why certain forms are chosen in a specific case and how they were used to create displays that offer new modes of interpretation. The birth of town planning as an architectural discipline When Marcello Piacentini (1881-1960) began his career at the turn of the 20th century, urban design as a profession for architects was a very young discipline. -

Watergate Landscaping Watergate Innovation

Innovation Watergate Watergate Landscaping Landscape architect Boris Timchenko faced a major challenge Located at the intersections of Rock Creek Parkway and in creating the interior gardens of Watergate as most of the Virginia and New Hampshire Avenues, with sweeping views open grass area sits over underground parking garages, shops of the Potomac River, the Watergate complex is a group of six and the hotel meeting rooms. To provide views from both interconnected buildings built between 1964 and 1971 on land ground level and the cantilivered balconies above, Timchenko purchased from Washington Gas Light Company. The 10-acre looked to the hanging roof gardens of ancient Babylon. An site contains three residential cooperative apartment buildings, essential part of vernacular architecture since the 1940s, green two office buildings, and a hotel. In 1964, Watergate was the roofs gained in popularity with landscapers and developers largest privately funded planned urban renewal development during the 1960s green awareness movement. At Watergate, the (PUD) in the history of Washington, DC -- the first project to green roof served as camouflage for the underground elements implement the mixed-use rezoning adopted by the District of of the complex and the base of a park-like design of pools, Columbia in 1958, as well as the first commercial project in the fountains, flowers, open courtyards, and trees. USA to use computers in design configurations. With both curvilinear and angular footprints, the configuration As envisioned by famed Italian architect Dr. Luigi Moretti, and of the buildings defines four distinct areas ranging from public, developed by the Italian firm Società Generale Immobiliare semi-public, and private zones. -

A British Reflection: the Relationship Between Dante's Comedy and The

A British Reflection: the Relationship between Dante’s Comedy and the Italian Fascist Movement and Regime during the 1920s and 1930s with references to the Risorgimento. Keon Esky A thesis submitted in fulfilment of requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences. University of Sydney 2016 KEON ESKY Fig. 1 Raffaello Sanzio, ‘La Disputa’ (detail) 1510-11, Fresco - Stanza della Segnatura, Palazzi Pontifici, Vatican. KEON ESKY ii I dedicate this thesis to my late father who would have wanted me to embark on such a journey, and to my partner who with patience and love has never stopped believing that I could do it. KEON ESKY iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This thesis owes a debt of gratitude to many people in many different countries, and indeed continents. They have all contributed in various measures to the completion of this endeavour. However, this study is deeply indebted first and foremost to my supervisor Dr. Francesco Borghesi. Without his assistance throughout these many years, this thesis would not have been possible. For his support, patience, motivation, and vast knowledge I shall be forever thankful. He truly was my Virgil. Besides my supervisor, I would like to thank the whole Department of Italian Studies at the University of Sydney, who have patiently worked with me and assisted me when I needed it. My sincere thanks go to Dr. Rubino and the rest of the committees that in the years have formed the panel for the Annual Reviews for their insightful comments and encouragement, but equally for their firm questioning, which helped me widening the scope of my research and accept other perspectives. -

A Case Study; People's Palace

A case Study; People’s Palace A case study of 20th century designs of buildings for ASSEMBLY, PRACTICING POLITICS, EXCHANGING KNOWLEDGE and RECREATION. This work is not intended to fully reconstruct the history and architectural typology of the people’s palace. By first constructing a framework of the changing society in the 20th century, and it’s relation to the shifts in economic and political structures, it presents case-studies of 8 buildings that in their own way illustrate the conflict between ideology, form, representation and function. Specifics of the building’s political itscontext physical and appearance,its architecture related are usedto the to intended construct client. an argument that helps the formation of an idea of what the architect’s intentions means for a structure and All texts are questioning the possibility of architecture to help the formation or representation of a community, in search of a contemporary way to apply this. IndEX 05-06 IntroductIon The necessity of a truly public space The cooperative’s houses as a place of resistance Architecture’s relation to politics and economy Buildings intended to form community 05 - 39 cASE StudIES of the history of the quarry in Heerlen / Heksenberg 09-12 BE Brussels - Victor Horta 13-16 RU Moscow - Konstantin Melnikov 17-20 21-24 FR Clichy - Jean Prouvé 25-28 IT Como - Terragni 29-32 NL Dronten - Frank van Klingeren 33-36 GBSE LondonEslöv - Hans - Cedric Asplund Price 37-40 BR Sao Paolo - Lina Bo Bardi IntroductIon thE EmErgencE of cApItAlism During the industrial revolution society went - through a gradual transformation, in which our accordingnew urban to fabric the new came processes into existence. -

ARCHITETTURA in ITALIA 1910 - 1980 Una Collezione Di Centodieci Libri E Documenti Originali

ARCHITETTURA IN ITALIA 1910 - 1980 Una collezione di centodieci libri e documenti originali L’ARENGARIO STUDIO BIBLIOGRAFICO Edizioni dell’Arengario Gussago Franciacorta 2017 ARCHITETTURA IN ITALIA 1910 - 1980 Una collezione di settandue libri e documenti originali a cura di Bruno Tonini, con un testo di Giovanni Michelucci L’ARENGARIO STUDIO BIBLIOGRAFICO “Io penso e credo in un tempo, vicino o lontano, in cui, come nelle antiche civiltà, tutto ciò che servirà alla vita sarà «vero», nato cioè spontaneamente con com- piuta conoscenza delle possibilità pratiche, economiche, tecniche e con piena convinzione che la struttura non si deve nascondere o mascherare ma svelare nella forma e che il «gusto» si modella sulla forma che nasce con l’urgenza e l’e- videnza di un fatto vitale. Allora le case, gli edifici pubblici, la forchetta, il ferro da stiro testimonieranno della unità d’intendimenti di un popolo, di affermare senza equivoco la propria realtà e la fiducia nella validità del proprio tempo: ogni oggetto troverà la sua forma nella collaborazione di una collettività, dove le qualità native diversissime di ciascuno potranno essere pienamente valorizzate e potenziate. Io non sono dunque libero dalle malìe della forma. Se ho insistito sul fattore eco- nomico è perché sono convinto che l’architettura non è nella varietà dei temi ma nella organizzazione di un’opera architettonica... Non credo tanto nella «im- maginazione» quanto invece nella «fantasia», che non sconfina mai nell’arbitrio, ma si vale appunto dei mezzi usuali e li dosa così, da ottenere variazioni infinite su pochi temi che esigenze economiche, sociali, tecniche hanno generalizzato.” Giovanni Michelucci [Giovanni Michelucci, Felicità dell’architetto, Firenze, Editrice Il Libro, 1949, pp. -

CENTRAL PAVILION, GIARDINI DELLA BIENNALE 29.08 — 8.12.2020 La Biennale Di Venezia La Biennale Di Venezia President Presents Roberto Cicutto

LE MUSE INQUIETE WHEN LA BIENNALE DI VENEZIA MEETS HISTORY CENTRAL PAVILION, GIARDINI DELLA BIENNALE 29.08 — 8.12.2020 La Biennale di Venezia La Biennale di Venezia President presents Roberto Cicutto Board The Disquieted Muses. Luigi Brugnaro Vicepresidente When La Biennale di Venezia Meets History Claudia Ferrazzi Luca Zaia Auditors’ Committee Jair Lorenco Presidente Stefania Bortoletti Anna Maria Como in collaboration with Director General Istituto Luce-Cinecittà e Rai Teche Andrea Del Mercato and with AAMOD-Fondazione Archivio Audiovisivo del Movimento Operaio e Democratico Archivio Centrale dello Stato Archivio Ugo Mulas Bianconero Archivio Cameraphoto Epoche Fondazione Modena Arti Visive Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea IVESER Istituto Veneziano per la Storia della Resistenza e della Società Contemporanea LIMA Amsterdam Peggy Guggenheim Collection Tate Modern THE DISQUIETED MUSES… The title of the exhibition The Disquieted Muses. When La Biennale di Venezia Meets History does not just convey the content that visitors to the Central Pavilion in the Giardini della Biennale will encounter, but also a vision. Disquiet serves as a driving force behind research, which requires dialogue to verify its theories and needs history to absorb knowledge. This is what La Biennale does and will continue to do as it seeks to reinforce a methodology that creates even stronger bonds between its own disciplines. There are six Muses at the Biennale: Art, Architecture, Cinema, Theatre, Music and Dance, given a voice through the great events that fill Venice and the world every year. There are the places that serve as venues for all of La Biennale’s activities: the Giardini, the Arsenale, the Palazzo del Cinema and other cinemas on the Lido, the theatres, the city of Venice itself. -

Italy Creates. Gio Ponti, America and the Shaping of the Italian Design Image

Politecnico di Torino Porto Institutional Repository [Article] ITALY CREATES. GIO PONTI, AMERICA AND THE SHAPING OF THE ITALIAN DESIGN IMAGE Original Citation: Elena, Dellapiana (2018). ITALY CREATES. GIO PONTI, AMERICA AND THE SHAPING OF THE ITALIAN DESIGN IMAGE. In: RES MOBILIS, vol. 7 n. 8, pp. 20-48. - ISSN 2255-2057 Availability: This version is available at : http://porto.polito.it/2698442/ since: January 2018 Publisher: REUNIDO Terms of use: This article is made available under terms and conditions applicable to Open Access Policy Article ("["licenses_typename_cc_by_nc_nd_30_it" not defined]") , as described at http://porto.polito. it/terms_and_conditions.html Porto, the institutional repository of the Politecnico di Torino, is provided by the University Library and the IT-Services. The aim is to enable open access to all the world. Please share with us how this access benefits you. Your story matters. (Article begins on next page) Res Mobilis Revista internacional de investigación en mobiliario y objetos decorativos Vol. 7, nº. 8, 2018 ITALY CREATES. GIO PONTI, AMERICA AND THE SHAPING OF THE ITALIAN DESIGN IMAGE ITALIA CREA. GIO PONTI, AMÉRICA Y LA CONFIGURACIÓN DE LA IMAGEN DEL DISEÑO ITALIANO Elena Dellapiana* Politecnico di Torino Abstract The paper explores transatlantic dialogues in design during the post-war period and how America looked to Italy as alternative to a mainstream modernity defined by industrial consumer capitalism. The focus begins in 1950, when the American and the Italian curated and financed exhibition Italy at Work. Her Renaissance in Design Today embarked on its three-year tour of US museums, showing objects and environments designed in Italy’s post-war reconstruction by leading architects including Carlo Mollino and Gio Ponti. -

The Watergate Project: a Contrapuntal Multi-Use Urban Complex in Washington, Dc

THE WATERGATE PROJECT: A CONTRAPUNTAL MULTI-USE URBAN COMPLEX IN WASHINGTON, DC Adrian Sheppard, FRAIC Professor of Architecture McGill University Montreal Canada INTRODUCTION Watergate is one of North America’s most imaginative and powerful architectural ensembles. Few modern projects of this scale and inventiveness have been so fittingly integrated within an existing and well-defined urban fabric without overpowering its neighbors, or creating a situation of conflict. Large contemporary urban interventions are usually conceived as objects unto themselves or as predictable replicas of their environs. There are, of course, some highly successful exceptions, such as New York’s Rockefeller Centre, which are exemplars of meaningful integration of imposing projects on an existing city, but these are rare. By today’s standards where significance in architecture is measured in terms of spectacle and flamboyance, Watergate is a dignified and rigorous urban project. Neither conventional as an urban design project, nor radical in its housing premise, it is nevertheless as provocative as anything in Europe. Because Moretti grasped the essence of Washington so accurately, he was able to bring to the city a new vision of urbanity. Watergate would prove to be an unequivocally European import grafted unto a typical North-American city, its most remarkable and successful characteristic being its relationship to its immediate context and the city in general. As an urban intervention, Watergate is an inspiring example of how a Roman architect, Luigi Moretti, succeeded in introducing a project of considerable proportions in the fabric of Washington, a city he had never visited before he received the commission. 1 Visually and symbolically, the richness of the traditional city is derived from the fact that there exists a legible distinction and balance between urban fabric and urban monument. -

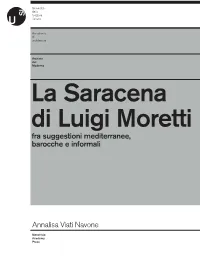

La Saracena Di Luigi Moretti Fra Suggestioni Mediterranee, Barocche E Informali

Università della Svizzera italiana Accademia di architettura Archivio del Moderno La Saracena di Luigi Moretti fra suggestioni mediterranee, barocche e informali Annalisa Viati Navone Mendrisio Academy Press 001 Orchestra_Saracena_pp1-18.qxp:Prime_Atti_F.qxp 2/6/12 4:51 PM Page 1 Archivio del Moderno / Saggi 20 Collana diretta da Letizia Tedeschi 001 Orchestra_Saracena_pp1-18.qxp:Prime_Atti_F.qxp 2/6/12 4:51 PM Page 2 001 Orchestra_Saracena_pp1-18.qxp:Prime_Atti_F.qxp 2/6/12 4:51 PM Page 3 La Saracena di Luigi Moretti fra suggestioni mediterranee, barocche e informali Annalisa Viati Navone Mendrisio Academy Press / 001 Orchestra_Saracena_pp1-18.qxp:Prime_Atti_F.qxp 2/6/12 4:51 PM Page 4 Coordinamento editoriale Tiziano Casartelli Redazione Marta Valdata Impaginazione e gestione immagini Sabine Cortat Le immagini provenienti dall’Archivio Centrale dello Stato di Roma (ACSRo) sono pubblicate con autorizzazione n. 946/2011. Le immagini provenienti dall’Archivio privato Moretti-Magnifico di Roma (AMMRo) sono pubbicate per gentile concessione dell’Architetto Tommaso Magnifico. La pubblicazione ha avuto il sostegno del Fondo Nazionale Svizzero per la Ricerca Scientifica In copertina: Villa La Saracena, scorcio del prospetto nord dal giardino d’ingresso (ACSRo) © 2012 Fondazione Archivio del Moderno, Mendrisio 001 Orchestra_Saracena_pp1-18.qxp:Prime_Atti_F.qxp 2/6/12 4:51 PM Page 5 Sommario 7 Prefazione Bruno Reichlin 13 Premessa 21 Storia e fortuna critica 47 L’analisi genetica dell’opera 71 “Mediterraneità”: un suggestivo intertesto 177 Barocco -

Cassani Simonetti Matteo Tesi.Pdf

Alma Mater Studiorum - Università di Bologna Dottorato di Ricerca in Architettonica Scuola di Dottorato in Ingegneria Civile ed Architettura XXVI Ciclo di Dottorato L’architettura di Piero Bottoni a Ferrara Occasioni di moderna composizione architettonica negli ambienti storici (1932-1971) Presentata da: Matteo Cassani Simonetti Coordinatore Dottorato: prof. Annalisa Trentin Relatore: prof. Giovanni Leoni Settore concorsuale: 08/E2 – Restauro e Storia dell’Architettura Settore scientifico disciplinare di afferenza: ICAR/18 Esame finale anno 2014 Intendo dire che la speculazione può spiccare il suo volo necessariamente spericolato con qualche prospettiva di successo, solo se, invece di indossare le ali di cera dell’esoterico, cerca la sua sorgente di forza unicamente nella costruzione. La costruzione richiedeva che la seconda parte del libro fosse formata essenzialmente di materiali filologici. Si tratta perciò meno di una «disciplina ascetica» che di una precau- zione metodologica…. Quando lei parla di una «esposizione allibita della fatticità», lei caratterizza in questo modo l’atteggiamento filologico genuino. Questo dovrebbe essere calato nella costruzione non solo per amore dei suoi risultati, ma come tale… l’apparenza della chiusa fatticità, che aderisce alla ricerca filologica e getta il ricercatore nell’incanto, svanisce nella misura in cui l’oggetto viene costruito nella prospettiva storica. Le linee di fuga di questa costruzione convergono nella nostra propria esperienza storica. Con ciò l’oggetto si costruisce come monade. Nella -

The Power of Images in the Age of Mussolini

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2013 The Power of Images in the Age of Mussolini Valentina Follo University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the History Commons, and the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation Follo, Valentina, "The Power of Images in the Age of Mussolini" (2013). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 858. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/858 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/858 For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Power of Images in the Age of Mussolini Abstract The year 1937 marked the bimillenary of the birth of Augustus. With characteristic pomp and vigor, Benito Mussolini undertook numerous initiatives keyed to the occasion, including the opening of the Mostra Augustea della Romanità , the restoration of the Ara Pacis , and the reconstruction of Piazza Augusto Imperatore. New excavation campaigns were inaugurated at Augustan sites throughout the peninsula, while the state issued a series of commemorative stamps and medallions focused on ancient Rome. In the same year, Mussolini inaugurated an impressive square named Forum Imperii, situated within the Foro Mussolini - known today as the Foro Italico, in celebration of the first anniversary of his Ethiopian conquest. The Forum Imperii's decorative program included large-scale black and white figural mosaics flanked by rows of marble blocks; each of these featured inscriptions boasting about key events in the regime's history. This work examines the iconography of the Forum Imperii's mosaic decorative program and situates these visual statements into a broader discourse that encompasses the panorama of images that circulated in abundance throughout Italy and its colonies.