Divergent Refugee and Tribal Cosmopolitanism in Dharamshala

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Temporal Change in Tree Species Composition in Palampur Forest

2019 Status Report Palampur Palampur Forest Division Temporal Change in Tree Species Composition in Palampur Forest Division of Dharamshala Forest Circle, Himachal Pradesh Harish Bharti, Aditi Panatu, Kiran and Dr. S. S. Randhawa H. P. State Centre on Climate Change (HIMCOSTE), Vigyan Bhawan near Udyog Bhawan, Bemloe Shimla-01 0177-2656489 Table of Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 4 Forests of Himachal Pradesh........................................................................................................................ 5 Study area and method ....................................................................................................................... 7 District Kangra A Background .................................................................................................................. 7 Location & Geographical– Area ................................................................................................................. 8 Palampur Forest Division- Forest Profile................................................................................................ 9 Name and Situation:- .................................................................................................................................. 9 Geology: ......................................................................................................................................................... 11 -

Dharamshala – Dalhousie -Amritsar

REPORT ON SHANTINIKETAN- AN EXCURSION CUM LEARNING TOUR Chandigarh- Manali - Dharamshala – Dalhousie -Amritsar 07-17 FEBRUARY, 2020 The Institute organized Shantiniketan- an Excursion Cum Learning Tour to Chandigarh- Manali - Dharamshala – Dalhousie -Amritsar from 07-17 February, 2020. 57 students of various PG programs accompanied by four faculty members and one staff member. Dr. Vipin Choudhary, Dr. Sopnamayee Acharaya, Dr. Shailshri Sharma, Prof. Pranay Karnik and Mr. Devendra Sen visited the beautiful places of Manali, Amritsar and Dalhousie, India. February 7-8, 2020- Chandigarh The students gathered at Indore railway station and boarded train from Indore to Ambala at 12:30 pm. The group reached Ambala at around 8.30 am on February 8, 2020 and Proceed towards Chandigarh. After taking breakfast and rest till lunch group visited Rock Garden and Sukhna Lake. The group started for Manali from Chandigarh by Bus and traveler after dinner and reached Manali at 9 am on February 9, 2020. February 9-11, 2020 – Manali After lunch at 2:30pm the group proceeds to visit the local places of Manali by local vehicles. Everybody enjoyed the shopping at Mall road of Manali on Feb 9, 2020 evening. On Feb 10, 2020 after breakfast the group proceeds to visit Sholang Valley. Students enjoyed ice and various adventures activities in Sholang and returned back to hotel by evening. A bonfire with light music has been arranged in the resort along with dinner. After dinner, the students rested overnight in the hotel. February 11-12, 2020 – Dharamshala Reached Dharmshala through Kulu on 11 Feb, 2020. Students Visited Kulu and enjoyed river rafting and travelled by road to Dharmshala. -

Kangra, Himachal Pradesh

` SURVEY DOCUMENT STUDY ON THE DRAINAGE SYSTEM, MINERAL POTENTIAL AND FEASIBILITY OF MINING IN RIVER/ STREAM BEDS OF DISTRICT KANGRA, HIMACHAL PRADESH. Prepared By: Atul Kumar Sharma. Asstt. Geologist. Geological Wing” Directorate of Industries Udyog Bhawan, Bemloe, Shimla. “ STUDY ON THE DRAINAGE SYSTEM, MINERAL POTENTIAL AND FEASIBILITY OF MINING IN RIVER/ STREAM BEDS OF DISTRICT KANGRA, HIMACHAL PRADESH. 1) INTRODUCTION: In pursuance of point 9.2 (Strategy 2) of “River/Stream Bed Mining Policy Guidelines for the State of Himachal Pradesh, 2004” was framed and notiofied vide notification No.- Ind-II (E)2-1/2001 dated 28.2.2004 and subsequently new mineral policy 2013 has been framed. Now the Minstry of Environemnt, Forest and Climate Change, Govt. of India vide notifications dated 15.1.2016, caluse 7(iii) pertains to preparation of Distt Survey report for sand mining or riverbed mining and mining of other minor minerals for regulation and control of mining operation, a survey document of existing River/Stream bed mining in each district is to be undertaken. In the said policy guidelines, it was provided that District level river/stream bed mining action plan shall be based on a survey document of the existing river/stream bed mining in each district and also to assess its direct and indirect benefits and identification of the potential threats to the individual rivers/streams in the State. This survey shall contain:- a) District wise detail of Rivers/Streams/Khallas; and b) District wise details of existing mining leases/ contracts in river/stream/khalla beds Based on this survey, the action plan shall divide the rivers/stream of the State into the following two categories;- a) Rivers/ Streams or the River/Stream sections selected for extraction of minor minerals b) Rivers/ Streams or the River/Stream sections prohibited for extraction of minor minerals. -

Program Annual Report Dharamshala

D O N E Waste Warriors Dharamshala Himachal Pradesh Project Report April 2019 - March 2020 Supported By: D O Table of Contents N E About Waste Warriors 1 Working Towards The UN SDGs 1 Project Overview 2 Our Objectives & Strategies 3 Our Team Green Workers 4 Office Staff 5 Our Achievements 6 Impact Data 7 Conferences, Exhibitions, and Workshops 8 School & Community Engagement 9 Art for Awareness 10 Event Waste Management 11 Awards and Accolades 12 Local News and Media 13 Our Dharamshala Partners 13 Testimonials 14 New Developments 16 Our Challenges 17 Measures Against COVID-19 17 Our Way Forward 18 Thank You To HT Parekh Foundation 19 About Waste Warriors About Waste Warriors Waste Warriors is a solid waste management NGO that was founded in 2012. We are a registered D society that works through a combination of direct action initiatives, awareness-raising and O community engagement programs, local advocacy, and long-term collaborative partnership with various government bodies. N Our Mission E Our mission is to develop sustainable solid waste management systems by being a catalyst for community-based decentralized initiatives in rural, urban, and protected areas, and to pioneer replicable models of waste management, innovative practices in awareness and education, and to formalize and improve the informal livelihoods and stigmatized conditions of waste workers. Working Towards The UN SDGs Good Health and Well-being: We promote waste segregation at source and divert organic waste through animal feeding and composting. Also, to curb and manage the burning of waste, we have strategically installed 10 dry leaf composting units, of which, 4 have been installed in schools. -

Judicial Officers at District Headquarters Dharamshala Sh

JUDICIAL OFFICERS AT DISTRICT HEADQUARTERS DHARAMSHALA SH. JITENDER KUMAR SHARMA, DISTRICT AND SESSIONS JUDGE KANGRA AT DHARAMSHALA Sh. J.K.Sharma, was born on 16-9-1964 at Mandi (H.P.). Passed matriculation examination from Govt. Vijay High School Mandi in 1979. Graduated from Vallabh Government Degree College Mandi in 1983. Obtained LL.B. Degree from H.P. University, Shimla, in 1986. Appointed as Sub Judge-cum-Judicial Magistrate and joined on 6-5-1991 at Bilaspur. Thereafter, remained posted at Rampur Bushehar, Jogindernagar, Sunder Nagar as Sub Judge-cum-Judicial Magistrate from 1991 till 1997. Thereafter, posted as Civil Judge-cum-ACJM, at Shimla, Nurpur and Ghumarwin from 1997 to 2006. Remained posted as Civil Judge (Sr. Division)-cum-CJM at Solan and Kangra at Dharamshala from may 2006 till September 2010. Qualified the Limited Competitive Exam for promotion in the Cadre of District Judges conducted by the Hon’ble High Court in June, 2010 and posted as Additional District and Sessions Judge(I) Kangra at Dharamshala (H.P.) in October, 2010. On placement as District & Sessions Judge in May 2012, posted as Director H.P. Judicial Academy, President Consumer Forum Shimla, Presiding Officer Labour Court Kangra at Dharamshala and District & Sessions Judge Sirmaur at Nahan till April 2016. Thereafter, worked as Registrar (Judicial) in the Hon’ble High Court, Shimla w.e.f 02.05.2016 to 22.12.2018. Currently, posted as District and Sessions Judge, Kangra Civil and Sessions Division at Dharamshala and assumed the charge as such on 24.12.2018. SH. PUNE RAM, PRINCIPAL JUDGE, FAMILY COURT KANGRA AT DHARAMSHALA Initially studied up to the Primary and High School standard in village Karjan and Haripur, Tehsil Manali, District Kullu (H.P.). -

18Th May Town Relaxation

GOVERNMENT OF HIMACHAL PRADESH OFFICE OF THE DEPUTY COMMISSIONER, CHAMBA DISTRICT CHAMBA (H.P.) No.CBA-DA-2(31)/2020-14085-14160 Dated: Chamba the 18th May, 2020 ORDER Whereas, the Government of Himachal Pradesh has decided to increase the lockdown measures to contain the spread of COVID-19 across the state. However, to mitigate the hardships to the general public due to restrictions already in place, I, Vivek Bhatia, District Magistrate, Chamba in exercise of the powers conferred upon me under Section 144 of the Criminal Procedure Code, 1973 and in partial modification of the order No. CBA-DA-2(31)/ 2020-5368-77 dated 22.04.2020 and its subsequent amendments, do hereby order the following with immediate effect: 1. Only one way entry shall be allowed between Main Chowk opposite Dogra Bazar to Post Office for people to avail the services of facilities thereby. 2. Both the ends of the roads between Chowgan No. 2 and 3, as well as between Chowgan No. 3 and 4 will be opened one/two way as per enforcement demand for facilitating transition between Kashmiri Mohalla and Main Bazar. 3. The vehicular traffic shall be managed as per the existing mechanism till further orders. These orders are strictly conditional and shall be subject to maintenance of social distancing in the core market areas. The Police department shall ensure the same and report if anything adverse is witnessed on the ground. This order shall come into force with immediate effect and shall remain in force till further orders. Issued under my hand and seal on 18th May, 2020. -

Forest Department, Himachal Pradesh

FOREST DEPARTMENT, HIMACHAL PRADESH Official E-mail Addresses & Telephone Numbers S.No. Designation Station Email Address Telephone No. 1 Principal CCF HP Shimla [email protected] 0177-2623155 2 Principal CCF (Wild Life) HP Shimla [email protected] 0177-2625205 3 Principal-cum-CPD MHWDP Solan [email protected] 01792-223043 4 APCCF (PFM & FDA) Shimla [email protected] 0177-2620281 5 APCCF (CAT Plan) Shimla [email protected] 0177-2626921 6 APCCF (PAN & BD) Shimla [email protected] 0177-2625036 7 APCCF (Projects) Shimla [email protected] 0177-2625036 8 OSD O/o PCCF WL HP Shimla [email protected] 0177-2625036 9 APCCF (Administration, P & D) Shimla [email protected] 0177-2623153 10 APCCF (FP & FC) Bilaspur [email protected] 01978-221616 11 APCCF (Research & NTFP) Sundernagar [email protected] 01907-264113 12 APCCF (FCA) Shimla [email protected] 0177-2623037 13 APCCF (Working Plan & Settlement) Mandi [email protected] 01905-237070 14 APCCF (Soil Conservation) Shimla [email protected] 0177-2622523 15 APCCF (HRD & TE) Shimla [email protected] 0177-2623153 16 APCCF (Finance & Planning) Shimla [email protected] 0177-2625036 17 APCCF (M & E) Shimla [email protected] 0177-2624376 18 CCF (PF/IT) Shimla [email protected] 0177-2625036 19 CCF (Eco-Tourism) Shimla [email protected] 0177-2623036 20 CCF (HPSEB) Shimla [email protected] 0177-2658710 21 CF (MIS & PG) Shimla [email protected] 0177-2620239 22 CF (Finance) Shimla [email protected] 0177-2627452 23 RPD MHWDP D/Shala Dharamshala [email protected] 01892-223345 24 RPD MHWDP Bilaspur Bilaspur -

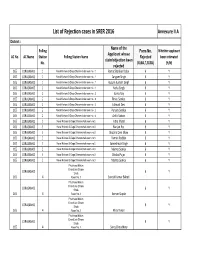

List of Rejection Cases in SRER 2016 Annexure II a District : Name of the Polling Form No

List of Rejection cases in SRER 2016 Annexure II A District : Name of the Polling Form No. Whether applicant Applicant whose AC No. AC Name Station Polling Station Name Rejected been intimated claim/objection been No. (6,6A,7,8,8A) (Y/N) rejected 165 JORASANKO 1 Naval Kishore B-Daga Dharamshala room no : 1 Rama Shankar Yadav 6 Y 165 JORASANKO 1 Naval Kishore B-Daga Dharamshala room no : 1 Sangam Singh 6 Y 165 JORASANKO 1 Naval Kishore B-Daga Dharamshala room no : 1 Kusum Kumari Singh 6 Y 165 JORASANKO 1 Naval Kishore B-Daga Dharamshala room no : 1 Neha Singh 6 Y 165 JORASANKO 2 Naval Kishore B-Daga Dharamshala room no : 2 Soma Ray 6 Y 165 JORASANKO 2 Naval Kishore B-Daga Dharamshala room no : 2 Rinku Sonkar 6 Y 165 JORASANKO 2 Naval Kishore B-Daga Dharamshala room no : 2 Lilawati Devi 6 Y 165 JORASANKO 2 Naval Kishore B-Daga Dharamshala room no : 2 Punam Sonkar 6 Y 165 JORASANKO 2 Naval Kishore B-Daga Dharamshala room no : 2 Ankit Sadani 6 Y 165 JORASANKO 3 Naval Kishore B-Daga Dharamshala room no;3 Indra Khatri 6 Y 165 JORASANKO 3 Naval Kishore B-Daga Dharamshala room no;3 Ranjan Roy 6 Y 165 JORASANKO 3 Naval Kishore B-Daga Dharamshala room no;3 Shobha Devi Shaw 6 Y 165 JORASANKO 3 Naval Kishore B-Daga Dharamshala room no;3 Yamini Poddar 6 Y 165 JORASANKO 3 Naval Kishore B-Daga Dharamshala room no;3 Kameshwar Singh 6 Y 165 JORASANKO 3 Naval Kishore B-Daga Dharamshala room no;3 Mamta Sonkar 6 Y 165 JORASANKO 3 Naval Kishore B-Daga Dharamshala room no;3 Diksha Pujari 6 Y 165 JORASANKO 3 Naval Kishore B-Daga Dharamshala room no;3 Mamta Sonkar 6 Y Phulchand Mukim Chand Jain Dharm JORASANKO Shala 6 Y 165 4 Room No. -

SR.N O. ITI Code ITI Name ITI Category Address State District Phone Number Email Name of FLC Name of Bank Name of FLC Manager Mo

STATE LEVEL BANKERS COMMITTEE HIMACHAL PRADESH CONVENOR : UCO BANK MAPPING OF VOACTIONAL TRAING CENTRES ( PRIVATE ITI s) in HIMACHAL PRADESH SR.N ITI Code ITI Name ITI Address State District Phone Number Email Name of FLC Name of Bank Name of FLC Mobile No. Of FLC Landline of FLC Address O. Category Manager Manager 1 PR02000016 Christian ITC Near B.D.O Office, Sarkaghat NULL SBOP-Ghumarwin Mr Hiralal 98055-12888 01978-255776 Main Market Road, Ghumar Win, Ghumarwin P HP Bilaspur SBOP-Ghumarwin 2 PR02000069 Satyam Private Industrial Vill. Awari, Po. Bhager 9736055202 [email protected] SBI-Kandrour Mr S.K.Setia 9805004303 01978-243034 Main Market Kandrour Training Institute P HP Bilaspur SBI-Kandrour 3 PR02000070 Maa Santoshi Private Luharwin, Tehsil Ghumarwin 01978-254245 [email protected] CBI-Ghumarwin Mr Yadvindar 97360-01239 01978-254333 Main Market Industrial Training Ghumarwin Institute P HP Bilaspur CBI-Ghumarwin 4 PR02000091 Sankhyan Pvt. ITI P.O & Tehsil, Ghumarwin 98165-98478 [email protected] OBC-Ghumarwin Mr Ranveer Singh 88947-21364 01978-254681 Main Market P HP Bilaspur OBC-Ghumarwin Ghumarwin 5 PR02000095 Adarsh Private Industrial VPO Swarghat, Tehsil Shri Naina 01978-284375 [email protected] UCO Bank-Swarghat Mr Vijay Bodh 94180-71045 01978-284022 Swarghat Training Institute Devi Ji m P HP Bilaspur UCO Bank-Swarghat 6 PR02000123 HIMS Private ITI Vill. Badhoo, Tehsil Ghumarwin 01978-221010 [email protected] HPSCB-Ghumarwin Miss Meera Bhogal 98160-26207 01978-255243 Main Market P Distt Bilaspur HP Bilaspur HPSCB-Ghumarwin Ghumarwin 7 PR02000145 Dogra Industrial Training Dogra 01978-223071 [email protected] UCO Bank Main Market Mr V.K.Dhiman 94180-82865 01978-222303 UCO Bank Main Market Center P HP Bilaspur UCO Bank Main Market Bilaspur 8 PR02000151 Santoshi Pvt. -

Additional Chief Secretary (Training&

Government of Himachal Pradesh Department of Personnel Appointment-1) No.Per(AI)B(15)-9/2020 Dated Shimla-2, the 28th April, 2021 NOTIFICATION The Governor, Himachal Pradesh, is pleased to order that during the election counting duty period of Dr. Sandeep Bhatnagar, IAS(HP:2001), Secretary(RD & PR, AR, RPG and Training & FA) to the Government of Himachal Pradesh, Shimla, who is holding the additional charge of the posts of Secretary, Lokayukta, Himachal Pradesh, Shimla and Secretary, Human Rights Commission, Himachall Pradesh, Shimla, Shri Akshay Sood, IAS(HP:2002), Secretary(Finance, Planning, Economics & Statistics, Cooperation and Housing) to the Government of Himachal Pradesh, Shimla, who is holding the additional charge of the post of Chief Executive Officer-cum-Secretary, HIMUDA, Shimla, Dr. Ajay Kumar Sharma IAS(HP:2003), Secretary(Ayurveda, Technical Education, Printing& Stationery) to the Government of Himachal Pradesh, Shimla, Shri Rajeev Sharma, IAS (HP:2004), Secretary(Education) to the Government of Himachal Pradesh, Shimla, Dr. S.S. Guleria, IAS(HP:2006), Secretary(Youth Services & Sports)to the Government of Himachal Pradesh, Shimla, who is also holding the additional charge of the posts of Divisional Commissioner, Kangra Division at Dharamshala, Himachal Pradesh and Chairman, Appellate Tax Tribunal at Dharamshala, District Kangra, Himachal Pradesh, Shri J.M. Pathania, IAS(HP:2008), Director(Personnel & Finance), H.P. State Electricity Board Ltd., Shimla, Shri Hans Raj Chauhan, IAS (HP:2008), Director, Land Records, Himachal Pradesh, Shimla, who is also holding he additional charge of the post of Managing Director, H.P. State Industrial Development Corporation, Shimla, Shri Rajesh Sharma, IAS(HP:2008), Special Secretary(Finance) to the Government of Himachal Pradesh, Shimla, Director, H.P. -

Tourism Update Mcleod Ganj Colour Coordinated: One of the Newer Buddhist Monasteries to Add to the Tibetan Cultural Ambience at Mcleod Ganj

TOURISM UPDATE MCLEOD GANJ Colour Coordinated: One of the newer Buddhist monasteries to add to the Tibetan cultural ambience at McLeod Ganj. Prayer Notes: Prayer wheels at McLeod Ganj monasteries are as a ritual turned daily by the monks. LI A Picture Perfect: A view of one of the streets in McLeod Ganj that is among the many vantage points providing a picturesque PHOTOS: ABHISHEK B view of the village. Discovering Tibet! A visit to Little Lhasa or McLeod Ganj is enriching. BY BINITA SINGH s a little girl growing up in Gaya, home to the famous centre of Buddhism, Bodh Gaya, I was intrigued by the Anglo Indian population in missionary schools. They were from the suburbs of Dharamshala, is situated in the some place called McCluskieganj, a place I believed to be in hilly terrains of Kangra district in Himachal Britain that was home to ‘foreigners’. Pradesh and is a popular Tibetan colony. ARecently, when I met a gentleman from the US who has been living in India Choosing not to miss out on the scenic drive to with his entire family for the past 14 years, it brought back a flash of childish Himachal Pradesh, we boarded the bus at Majnu memories when he mentioned his home was in McLeod Ganj, Dharamshala. ka Tila in North Campus, Delhi, which inciden- The similarity in their names also set me on a journey of discovery—of McLeod tally is a Tibetan hub. If inclined you may even Ganj. The bonus was the summer weekend getaway’s proximity to Delhi. -

Rohtang Pass- Dalhousie – Dharamshala- Chandigarh - Delhi

Destinations Covered : Delhi- Shimla – Manali- Rohtang Pass- Dalhousie – Dharamshala- Chandigarh - Delhi DAY 01 : DELHI – SHIMLA (343 kms ) On arrival pick up from Delhi Airport / Railway station. Proceed from Delhi to Shimla, Check invto Hotel & fresh n up. Evening is free at leisure. Overnight stay at hotel in SHIMLA. DAY 02 : SHIMLA LOCAL SIGHT SEEINGs After morning breakfast proceed to lacal city tour. Visit Indian Institite of Advanced Studies, Sanket Mochan Temple, And Jhaku Temple . After Lunch evening is free to explore famouse shopping places in Shimla Town, The Mall & The ridge. Overnight stay at Hotel in SHIMLA. DAY 03 : SHIMLA –MANALI ( 250 Kms) After morning breakfast drive to Manali. Enroute visit Kullu. Major attraction in Kullu are - Handloom Kullu Shawl , Raghunath Temple, Maha Devi Tirth Temple- popularly known as Vaishno Devi Mandir (by localities), Raison ( camping site), Shoja ( snow point) , Basheshwar Mahadev Temple. On arrival check in to Hotel & fresh n up. Evening is free at leisure. Overnight at hotel in MANALI. DAY 04 : MANALI LOCAL SIGHT SEEING After morning breakfast proceed for Local sightseeing in Manali. You can visit Hadimba or Dhungiri temple , Devi Temple, Manu Temple, Vashishta Village .After lunch evening is free to take a walk at Mall road & visit some Tibetan Monasteries. Overnight stay at hotel in MANALI. DAY 05: MANALI - ROHTANG PASS – MANALI ( 55 Kms/ One way )/ LEISURE After morning breakfast Full day tour of Rohtang Pass – The majesty of the mountains and the glaciers can be seen at their best, you have next two hours to enjoy this snowy haven. Take a sledge ride down the slopes, try your luck climbing the little snow hills.