Essays Controversies the War of 1812 Essays

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SR V15 Cutler.Pdf (1.135Mb)

WHISKEY, SOLDIERS, AND VOTING: WESTERN VIRGINIA ELECTIONS IN THE 1790s Appendix A 1789 Montgomery County Congressional Poll List The following poll list for the 1789 congressional election in Montgomery County appears in Book 8 of Montgomery County Deeds and Wills, page 139. Original spellings, which are often erroneous, are preserved. The list has been reordered alphabetically. Alternative spellings from the tax records appear in parentheses. Other alternative spellings appear in brackets. Asterisks indicate individuals for whom no tax record was found. 113 Votes from February 2, 1789: Andrew Moore Voters Daniel Colins* Thomas Copenefer (Copenheefer) Duncan Gullion (Gullian) Henry Helvie (Helvey) James McGavock John McNilt* Francis Preston* 114 John Preston George Hancock Voters George Adams John Adams Thomas Alfred (Alford) Philip Arambester (Armbrister) Chales (Charles) Baker Daniel Bangrer* William Bartlet (Berlet) William Brabston Andrew Brown John Brown Robert Buckhanan William Calfee (Calfey) William Calfee Jr. (Calfey) James Campbell George Carter Robert Carter* Stophel Catring (Stophell Kettering) Thadeus (Thaddeas) Cooley Ruebin Cooley* Robert Cowden John Craig Andrew Crocket (Crockett) James Crockett Joseph Crocket (Crockett) Richard Christia! (Crystal) William Christal (Crystal) Michel Cutney* [Courtney; Cotney] James Davies Robert Davies (Davis) George Davis Jr. George Davis Sr. John Davis* Joseph Davison (Davidson) Francis Day John Draper Jr. Charles Dyer (Dier) Joseph Eaton George Ewing Jr. John Ewing Samuel Ewing Joseph -

Indianapolis Germans and the Beginning Ofthe Civil War/ Based

CHAPTER XIII THE CIVIL WAR We shall really see what Germans patriots can do! August Willich, German immigrant, commander of the Indiana 32nd (German) Regiment, and Union general, 1861. In the Civil War it would be difficult to paint in too strong colors what I may well-nigh call the all importance of the American citizens of German birth and extraction toward the cause of Union and Liberty. President Theodore Roosevelt, 1903. Chapter XIII THE CIVIL WAR Contents INTRODUCTION 1. HOOSIER GERMANS IN THE WAR FOR THE UNION William A. Fritsch (1896) 2. THE GERMANS OF DUBOIS COUNTY Elfrieda Lang 2.1 REMEMBERING TWO CIVIL WAR SOLDIERS: NICHOLAS AND JOHN KREMER OF CELESTINE, DUBOIS COUNTY George R. Wilson 3. FIGHTING FOR THE NEW FATHERLAND: INDIANAPOLIS GERMANS AND THE BEGINNING OF THE WAR Theodore Stempfel 4. DIE TURNVEREINE (THE TURNERS) Mark Jaeger 5. WAR CLOUDS OVER EVANSVILLE James E. Morlock 6. CAPTAIN HERMAN STURM AND THE AMMUNITION PROBLEM Jacob Piatt Dunn (1910) 6.1 COLONEL STURM Michael A. Peake, (ed) 7. THE FIRST INDIANA BATTERY, LIGHT ARTILLERY Frederick H. Dyer 7.1 FIRST INDIANA BATTERY VETERAN CHRISTIAN WUNDERLICH History of Vanderburgh County 8. THE SIXTH INDIANA BATTERY, LIGHT ARTILLERY 8.1 JACOB LOUIS BIELER, VETERAN OF SHILOH Jacob Bieler Correspondence 8.2 JACOB L. BIELER Jacob Piatt Dunn (1919) 9. 32ND REGIMENT INDIANA INFANTRY ("1st GERMAN REGIMENT") Frederick H. Dyer 1 10. AUGUST WILLICH-THE ECCENTRIC GERMAN GENERAL Karen Kloss 11. PRESS COVERAGE—1st GERMAN, 32nd REGIMENT INDIANA VOLUNTEERS Michael A. Peake, (ed) 12. THE NATION’S OLDEST CIVIL WAR MONUMENT Michael A. -

High Army Leadership in the Era of the War of 1812: the Making and Remaking of the Officer Corps William B. Skelton the William

High Army Leadership in the Era of the War of 1812: The Making and Remaking of the Officer Corps William B. Skelton The William and Mary Quarterly, 3rd Ser., Vol. 51, No. 2. (Apr., 1994), pp. 253-274. Stable URL: http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0043-5597%28199404%293%3A51%3A2%3C253%3AHALITE%3E2.0.CO%3B2-W The William and Mary Quarterly is currently published by Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/about/terms.html. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/journals/omohundro.html. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is an independent not-for-profit organization dedicated to and preserving a digital archive of scholarly journals. For more information regarding JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. http://www.jstor.org Sat Jun 9 13:30:49 2007 High Army Leadership in the Era of the War of 1812: The Making and Remaking of the Officer Corps William B. -

Source Index

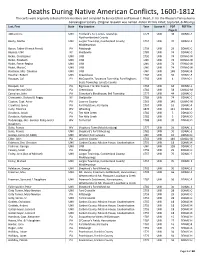

Deaths During Native American Conflicts, 1600-1812 The cards were originally collected from members and compiled by Eunice Elliott and Samuel C. Reed, Jr. for the Western Pennsylvania Genealogical Society. (Original research was named Indian Victims Killed, Captured, & Missing) Last, First State Key Location Year Source # PDF PDF File Page # 108 settlers UNK Freeland’s Fort, Lewis Township, 1779 UNK 48 DDNAC-F Northumberland County Barcly, Matha UNK Lurgan Township, Cumberland County; 1757 UNK 70 DDNAC-F Middlesprings Baron, Father (French Priest) PA Pittsburgh 1759 UNK 29 DDNAC-G Bayless, UNK KY Shelbyville 1789 UNK 74 DDNAC-C Bickel, Christopher UNK UNK 1792 UNK 74 DDNAC-W Bickel, Elizabeth UNK UNK UNK UNK 74 DDNAC-W Bickel, Esther Regina UNK UNK UNK UNK 74 DDNAC-W Bickel, Maria C UNK UNK UNK UNK 74 DDNAC-W Boatman, Mrs. Claudina UNK UNK UNK UNK 148 DDNAC-B Boucher, Robert UNK Greensburg 1782 UNK 56 DDNAC-F Bouquet, Col. PA McCoysville, Tuscarora Township; Fort Bingham; 1756 UNK 4 DDNAC-I Beale Township, Juniata County Bouquet, Col. PA Big Cove, Franklin County 1763 UNK 64 DDNAC-L Brownlee and Child PA Greensburg 1782 UNK 58 DDNAC-M Carnahan, John PA Carnahan’s Blockhouse, Bell Township 1777 UNK 44 DDNAC-C Chenoweth, Richard & Peggy KY Shelbyville 1789 UNK 74 DDNAC-C Clayton, Capt. Asher PA Luzerne County 1763 UNK 140 DDNAC-W Crawford, James PA Fort Redstone; Kentucky 1767 UNK 16 DDNAC-R Curly, Florence WV Wheeling 1876 UNK 141 DDNAC-S Davidson, Josiah PA Ten Mile Creek 1782 UNK 5 DDNAC-D Davidson, Nathaniel PA Ten Mile Creek 1782 UNK 5 DDNAC-D Dodderidge, Mrs. -

William Preston and the Revolutionary Settlement

Journal of Backcountry Studies EDITOR’S NOTE: This is the third and last installment of the author’s 1990 University of Maryland dissertation, directed by Professor Emory Evans, to be republished in JBS. Dr. Osborn is President of Pacific Union College. William Preston and the Revolutionary Settlement BY RICHARD OSBORN Patriot (1775-1778) Revolutions ultimately conclude with a large scale resolution in the major political, social, and economic issues raised by the upheaval. During the final two years of the American Revolution, William Preston struggled to anticipate and participate in the emerging American regime. For Preston, the American Revolution involved two challenges--Indians and Loyalists. The outcome of his struggles with both groups would help determine the results of the Revolution in Virginia. If Preston could keep the various Indian tribes subdued with minimal help from the rest of Virginia, then more Virginians would be free to join the American armies fighting the English. But if he was unsuccessful, Virginia would have to divert resources and manpower away from the broader colonial effort to its own protection. The other challenge represented an internal one. A large number of Loyalist neighbors continually tested Preston's abilities to forge a unified government on the frontier which could, in turn, challenge the Indians effectivel y and the British, if they brought the war to Virginia. In these struggles, he even had to prove he was a Patriot. Preston clearly placed his allegiance with the revolutionary movement when he joined with other freeholders from Fincastle County on January 20, 1775 to organize their local county committee in response to requests by the Continental Congress that such committees be established. -

Free Land Attracted Many Colonists to Texas in 1840S 3-29-92 “No Quitting Sense” We Claim Is Typically Texas

“Between the Creeks” Gwen Pettit This is a compilation of weekly newspaper columns on local history written by Gwen Pettit during 1986-1992 for the Allen Leader and the Allen American in Allen, Texas. Most of these articles were initially written and published, then run again later with changes and additions made. I compiled these articles from the Allen American on microfilm at the Allen Public Library and from the Allen Leader newspapers provided by Mike Williams. Then, I typed them into the computer and indexed them in 2006-07. Lois Curtis and then Rick Mann, Managing Editor of the Allen American gave permission for them to be reprinted on April 30, 2007, [email protected]. Please, contact me to obtain a free copy on a CD. I have given a copy of this to the Allen Public Library, the Harrington Library in Plano, the McKinney Library, the Allen Independent School District and the Lovejoy School District. Tom Keener of the Allen Heritage Guild has better copies of all these photographs and is currently working on an Allen history book. Keener offices at the Allen Public Library. Gwen was a longtime Allen resident with an avid interest in this area’s history. Some of her sources were: Pioneering in North Texas by Capt. Roy and Helen Hall, The History of Collin County by Stambaugh & Stambaugh, The Brown Papers by George Pearis Brown, The Peters Colony of Texas by Seymour V. Conner, Collin County census & tax records and verbal history from local long-time residents of the county. She does not document all of her sources. -

Available to Download

A Desert Between Us & Them INTRODUCTION The activities and projects in this guide have been developed to compliment the themes of the A Desert Between Us & Them documentary series. These ideas are meant to be an inspiration for teachers and students to become engaged with the material, exercise their creative instincts, and empower their critical thinking. You will be able to adapt the activities and projects based on the grade level and readiness of your students. The International Society for Technology in Education (http://www.iste.org) sets out standards for students to “learn effectively and live productively in an increasingly global and digital world.” These standards, as described in the following pages, were used to develop the activities and projects in this guide. The Ontario Visual Heritage Project offers robust resources on the A Desert Between Us & Them website http://1812.visualheritage.ca. There is a link to additional A Desert Between Us & Them stories posted on our YouTube Channel, plus the new APP for the iPad, iPhone and iPod. A Desert Between Us & Them is one in a series of documentaries produced by the Ontario Visual Heritage Project about Ontario’s history. Find out more at www.visualheritage.ca. HOW TO NAVIGATE THIS GUIDE In this guide, you will find a complete transcript of each episode of A Desert Between Us & Them. The transcripts are broken down into chapters, which correspond with the chapters menus on the DVD. Notable details are highlighted in orange, which may dovetail with some of the projects and activities that you have already planned for your course unit. -

Washington and Saratoga Counties in the War of 1812 on Its Northern

D. Reid Ross 5-8-15 WASHINGTON AND SARATOGA COUNTIES IN THE WAR OF 1812 ON ITS NORTHERN FRONTIER AND THE EIGHT REIDS AND ROSSES WHO FOUGHT IT 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Illustrations Maj. Gen. Jacob Brown 3 Map upstate New York locations 4 Map of Champlain Valley locations 4 Chapters 1. Initial Support 5 2. The Niagara Campaign 6 3. Action on Lake Champlain at Whitehall and Training Camps for the Green Troops 10 4. The Battle of Plattsburg 12 5. Significance of the Battle 15 6. The Fort Erie Sortie and a Summary of the Records of the Four Rosses and Four Reids 15 7. Bibliography 15 2 Maj. Gen. Jacob Brown as depicted3 in an engraving published in 1862 4 1 INITIAL SUPPORT Daniel T. Tompkins, New York’s governor since 1807, and Peter B. Porter, the U.S. Congressman, first elected in 1808 to represent western New York, were leading advocates of a war of conquest against the British over Canada. Tompkins was particularly interested in recruiting and training a state militia and opening and equipping state arsenals in preparation for such a war. Normally, militiamen were obligated only for three months of duty during the War of 1812, although if the President requested, the period could be extended to a maximum of six months. When the militia was called into service by the governor or his officers, it was paid by the state. When called by the President or an officer of the U.S. Army, it was paid by the U.S. Treasury. In 1808, the United States Congress took the first steps toward federalizing state militias by appropriating $200,000 – a hopelessly inadequate sum – to arm and train citizen soldiers needed to supplement the nation’s tiny standing army. -

River Raisin National Battlefield Park Lesson Plan Template

River Raisin National Battlefield Park 3rd to 5th Grade Lesson Plans Unit Title: “It’s Not My Fault”: Engaging Point of View and Historical Perspective through Social Media – The War of 1812 Battles of the River Raisin Overview: This collection of four lessons engage students in learning about the War of 1812. Students will use point of view and historical perspective to make connections to American history and geography in the Old Northwest Territory. Students will learn about the War of 1812 and study personal stories of the Battles of the River Raisin. Students will read and analyze informational texts and explore maps as they organize information. A culminating project will include students making a fake social networking page where personalities from the Battles will interact with one another as the students apply their learning in fun and engaging ways. Topic or Era: War of 1812 and Battles of River Raisin, United States History Standard Era 3, 1754-1820 Curriculum Fit: Social Studies and English Language Arts Grade Level: 3rd to 5th Grade (can be used for lower graded gifted and talented students) Time Required: Four to Eight Class Periods (3 to 6 hours) Lessons: 1. “It’s Not My Fault”: Point of View and Historical Perspective 2. “It’s Not My Fault”: Battle Perspectives 3. “It’s Not My Fault”: Character Analysis and Jigsaw 4. “It’s Not My Fault”: Historical Conversations Using Social Media Lesson One “It’s Not My Fault!”: Point of View and Historical Perspective Overview: This lesson provides students with background information on point of view and perspective. -

The Wyoming Massacre in the American Imagination

Virginia Commonwealth University VCU Scholars Compass Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2021 "Savage and Bloody Footsteps Through the Valley" : The Wyoming Massacre in the American Imagination William R. Tharp Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd Part of the Cultural History Commons, and the United States History Commons © The Author Downloaded from https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd/6707 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at VCU Scholars Compass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of VCU Scholars Compass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “Savage and Bloody Footsteps Through the Valley” The Wyoming Massacre in the American Imagination A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts at Virginia Commonwealth University By. William R. Tharp Dr. Carolyn Eastman, Advisor Associate Professor, Department of History Virginia Commonwealth University Richmond, Virginia 14 May 2021 Tharp 1 © William R. Tharp 2021 All Rights Reserved Tharp 2 Abstract Along the banks of the Susquehanna River in early July 1778, a force of about 600 Loyalist and Native American raiders won a lopsided victory against 400 overwhelmed Patriot militiamen and regulars in the Wyoming Valley of Pennsylvania. While not well-known today, this battle—the Battle of Wyoming—had profound effects on the Revolutionary War and American culture and politics. Quite familiar to early Americans, this battle’s remembrance influenced the formation of national identity and informed Americans’ perceptions of their past and present over the course of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. -

War of 1812 Travel Map & Guide

S u sq u eh a n n a 1 Westminster R 40 r e iv v e i r 272 R 15 anal & Delaware C 70 ke Chesapea cy a Northeast River c o Elk River n 140 Havre de Chesapeake o 97 Grace City 49 M 26 40 Susquehanna 213 32 Flats 301 13 795 95 1 r e Liberty Reservoir v i R Frederick h 26 s 9 u B 695 Elk River G 70 u 340 n Sa p ssaf 695 rass 83 o Riv w er r e d 40 e v i r R R Baltimore i 13 95 v e r y M c i 213 a dd c le o B R n 70 ac iv o k e R r M 270 iv e 301 r P o to m ac 15 ster Che River 95 P 32 a R t i v a 9 e r p Chestertown 695 s 13 co R 20 1 i 213 300 1 ve r 100 97 Rock Hall 8 Leesburg 97 177 213 Dover 2 301 r ive r R e 32 iv M R 7 a r k got n hy te Ri s a v t 95 er e 295 h r p 189 S e o e C v 313 h ve i r C n R R e iv o er h 13 ka 267 495 uc 113 T Whitehall Bay Bay Bridge 50 495 Greensboro 193 495 Queen Milford Anne 7 14 50 Selby 404 Harrington Bay 1 14 Denton 66 4 113 y P 258 a a B t u rn 404 x te 66 Washington D.C. -

Military Occurrences

A. FULL AND CORRECT ACCOUNT OF THE MILITARY OCCURRENCES OF LHC THE LATE WAR 973.3 BETWEEN J29 GREAT BRITAIN AND THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA; WITH AN APPENDIX, AND PLATES. BY WILLIAM JAMES, AUTHOR OF " A FULL AND CORRECT ACCOUNT OF THE CHIEF NAVAL OCCURRENCES, &C." .ellterum alterius auxilio eget. SALLUST. IN TWO VOLUMES. VOL. II. Unbolt : PRINTED FOR THE AUTHOR: SOLD BY BLACK, KINGSBURY, PARBURY, AND ALLEN, LEADENHALL-STREET; - JAMES M. RICHARDSON, CORNHILL ; JOHN BOOTH, DUKE STREET / PoRTLAN D -PLACE ;. AND ALL OTHER BOOKSELLERS. 1818. .44 '1) 1" 1'.:41. 3 1111 MILITARY OCCURRENCES, .c. 4. CHAPTER XI. British force on the Niagara in October, 1813 — A ttack upon the piquets—Effects of the surrender of the right division—Major-general Vincent's retreat to Burlington— His orders from the commander-in-clarf to retire upon Kingston— Fortunate contravention of those orders—General Harrison's arrival at, and departure from Fort- George Association of some Upper Canada militia after being disembodied—Their gallant attack upon, and capture of, a band of plunder-. ing traitors—General M'Clure's shameful con , duct towards the Canadian inhabitants—Colonel Murray's gallant behaviour Its effect upon general M'Clure—A Canadian winter—Night- conflagration of Newark by the Americians- M'Clure's abandonment of Fort-George, and flight across the river=–Arrival of lieutenant- general DruMmond—Assault upon, and capture of Fort-Niagara — Canadian prisoners found there Retaliatory destruction of LeWistown, VOL. Jr. MILITARY OCCURRENCES BETWEEN GREAT BRITAIN AND AMERICA. 3 Youngstown,Illanchester ,and Tuscarora—Attack consisting of 1100 men, with the great general upon Bufaloe and Black Rock, and destruction Vincent, at their head, fled into the woods." Of those ifillagei—Americaii resentment against The British are declared to have sustained a general 31' Clure—Rernarks upon the campaign ; loss of 32 in killed only, and the Americans of also upon the burning of Newark, and the four killed and wounded.