A Vision for Women's Health Research

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Global Shapers Community Annual Meeting 2017 Participant List

Global Shapers Community Annual Meeting 2017 Participant List January 2017 Photo Profile Hub Country Abdullahi Alim Perth Hub Australia Head, Practice, The Lighthouse Strategy Abdullahi came to Australia as a Somali refugee at the age of five. At 23, he is pursuing studies at Stanford University. Now, through the Lighthouse Strategy, Abdullahi runs ‘hackathons’ that bring young innovators together to develop solutions to global challenges. Abdullahi’s approach has attracted partners from the Australian Government to Google and the US Department of State. For example, MYHACK, an anti-extremism hackathon he coordinates, has seen young Australians create digital solutions to undermine the influence and pervasive appeal of violent extremist propaganda. Abdullahi’s goal is to create ‘lighthouses’ around the world to promote social impact and youth entrepreneurship. He’s set his sights on innovation challenges to empower more young Australians to solve issues including the refugee crisis and Indigenous disadvantage in the West. Ana Cristina Vargas Caracas Hub Venezuela Founder and Director, Ana Vargas Arquitectura Ana is an architect based in Caracas, Venezuela, has worked in Italy, India and USA. She holds an Architecture Degree from Universidad Central de Venezuela and an MSC in Architecture (2010) and Urbanism from Massachusetts Institute of Technology, MIT (2014). Her work focuses on projects related to participatory urban design. Ana established her own architecture practice in 2015 and based on her MIT thesis founded Tracing Public Space (Trazando Espacios) an NGO focused on teaching children urban design skills to transform public spaces within their communities. Trazando Espacios has done projects in India, Chile, USA and Venezuela. -

Interfaith Scroll 7 9-25-18 Print

Bill Ford, Executive Chairman Jim Hackett, CEO Ford Motor Company, Dear Mr. Ford, and Mr. Hackett, In 2011, Ford Motor Company was part of a historic breakthrough in cooperation on climate solutions when the company supported the Clean Car Standards, which would raise fuel eciency standards to an average of 54.5 miles per gallon by 2025. As people of faith who care for Earth and all of its inhabitants, we cheered this progress. Then, under the current Administration, Ford began lobbying for a review of the standards, asking for “additional exibility” in meeting them. Despite the debt Ford owes to the American taxpayers for billions of dollars to invest in advanced vehicle manufacturing, you now seem ready to go back on your commitment to cleaner cars for American drivers. This is unconscionable. We call on you to stand by the Clean Car Standards. The Ford name carries a legacy of innovative technological advancements for the good of society. The Clean Car Standards gave Ford an opportunity to continue this legacy of innovation and bolster its stated commitment to sustainability. We hoped that Ford would look to the future and compete with China and Europe on the clean cars of tomorrow, while cleaning up our air at home and saving families money at the pump. Today, the transportation sector is the single largest and fastest growing source of carbon pollution in the U.S. Cars and pickup trucks account for 47 percent of oil used in the United States and nearly one third of our greenhouse gas emissions. This trend makes the Clean Car Standards we adopted seven years ago even more prescient and important. -

Ally Hand Weapons Designed for Use Against Armor

University of Massachusetts Boston The University Mace Symbols of authority and power, maces were originally hand weapons designed for use against armor. Topped by the flame of knowledge, the University mace has the University seal as a focal point and unifying element. Tassels of maroon and white hang from the shaft of fourteen rods of black walnut, symbolizing the fourteen counties of the Commonwealth. The head of the mace is gold plate over highly polished brass. Complex curves radiating from the hub in which the seal is centered reflect light in constantly changing patterns, symbolic of the many-faceted environment of the university life. Academic Costume and Regalia The academic regalia worn by faculty and students at this ceremony repre sent traditions which come down from the Middle Ages, when European universities were institutions of the church. At that time, robes were a common form of dress, particularly for officials of church and state. The cut of the robe, its adornment, and the colors used comprised a specialized heraldry that conveyed the rank and station of the wearer. At the universities, both faculty and students were considered to be part of the church hierarchy and were expected to wear the prescribed gowns. As society moved toward more modern forms of dress, only royalty, clergy, judges, and academics retained the traditional regalia, reserving it only for ceremonial use. Modern academic regalia retain some of the symbols of the earlier forms of ceremonial dress. The gown tends to be fullest, longest, and heaviest for the doctoral degree. The sleeves for the bachelor's and master's gowns are typi cally open at the wrist. -

From Science to Business: Preparing Female Scientists and Engineers for Successful Transition Into Entrepreneurship ______

FROM SCIENCE TO BUSINESS: PREPARING FEMALE SCIENTISTS AND ENGINEERS FOR SUCCESSFUL TRANSITION INTO ENTREPRENEURSHIP ________________________________________________________________________________________________________ FROM SCIENCE TO BUSINESS: PREPARING FEMALE SCIENTISTS AND ENGINEERS FOR SUCCESSFUL TRANSITION INTO ENTREPRENEURSHIP A WORKSHOP August 31 – September 1, 2009 The National Academies The Beckman Center 100 Academy Irvine, CA 92617 ______________________________________________________________________________ THE NATIONAL ACADEMIES 1 August 31 – September 1, 2009 FROM SCIENCE TO BUSINESS: HOW TO PREPARE FEMALE SCIENTISTS AND ENGINEERS TO SUCCESSFULLY TRANSITION INTO ENTREPRENEURSHIP ________________________________________________________________________________________________________ CONTENTS Agenda 3 Committee Mandate and Membership 6 Biographies 7 List of Registrants 17 ______________________________________________________________________________ THE NATIONAL ACADEMIES 2 August 31 – September 1, 2009 FROM SCIENCE TO BUSINESS: HOW TO PREPARE FEMALE SCIENTISTS AND ENGINEERS TO SUCCESSFULLY TRANSITION INTO ENTREPRENEURSHIP ________________________________________________________________________________________________________ AGENDA August 31: Framing Issues and Strategies -- Where We Stand 9:00 am Welcome and Introductions Lilian Wu, Chair, Committee on Women in Science, Engineering, and Medicine and Program Executive, Global University Programs, IBM 9:05 am Study: Entrepreneurial Careers of Women Chair: Susan Wessler, -

Study Guide DRAFT

STEM Women Study Guide 2 STEM Women Study Guide A Project of Women Ground Breakers Thanking our 2015 Sponsors Platinum Sponsors: Chattanooga Area Chamber of Commerce, Humanities Tennessee Gold Sponsors: American Diversity Report, Chattanooga Writers Guild, EPB Fiber Optics excellerate!, Million Women Mentors, Nashville Area Hispanic Chamber of Commerce Foundation, Southern Adventist University, The HR Shop, ThreeTwelve Creative, UTC College of Engineering and Computer Science, Volkswagen Chattanooga. Special Thanks to Southern Adventist University Intern Abigail White Published March 2015 American Diversity Report Chattanooga, TN 3 TABLE of CONTENTS Bios & Discussion Questions Ada Lovelace…………………………………………………………………5 Alice Augusta Ball...........................................................................................6 Anita Borg……………………………………………………………………7 Annie J. Easley……………………………………………………………….8 Asima Chatterjee……………………………………………………………..9 Bessie Virginia Blount……………………………………………………….10 Carolyn Denning……………………………………………………………..11 Charlotte Scott………………………………………………………………..12 Emily Roebling………………………………………………………………13 EXERCISE #1: Thinking STEM……………………………………………14 Emmy Noether……………………………………………………………….15 Grace Hopper………………………………………………………………..16 EXERCISE #2: Writing Your Story……………………………..…………..17 Giuliana Tesoro……………………………………………………………...18 Hattie Alexander…………………………………………………………….20 Helen Newton Turner…………………………………………………….....21 Hypatia……………………………………………………………………....22 Jane Cooke Wright…………………………………………………………..23 Jewel Plummer………………………………………………………………24 -

Will Touch Many Lives the Ripple of My

The Report on Philanthropy 2009–2010 The ripple of my will touch many lives Philanthropy Report | 1 World A Spelman education goes beyond the student to everyone that she touches. 2 | Philanthropy Report Parent donors and student donors also did their part to make this a banner fundraising year at Spelman. Parents gave in record numbers, as did current undergraduates. Some 60 percent of seniors participated in the The Senior World Legacy Gift program in honor of their graduation year, Letter from the President receiving a Spelman blue commemorative tassel that they proudly displayed during the Founders Day convocation. Faculty and staff added to the year’s fundraising successes by increasing their number of donors almost 7 percent and Greetings, increasing the number of dollars by almost 21 percent. I am happy to share that including alumnae employees, this group Spelman women are making an impact can boast an overall participation of 50 percent in 2009–2010. in many ways every day. Our alumnae are running national corporations, making All of these gifts allow Spelman College to offer more global scientific research contributions, and engagement opportunities, enhanced research experiences, founding nonprofit organizations. Our and additional career-related internships to our students. faculty are bringing real-world experiences from government, They expand service learning and community engagement philanthropy, and corporate America to teach and inspire the for the women on our campus with the world nearby and next generation of national and local leaders. Our students across oceans. are engaged in mitigating large-scale disasters, from raising money for housing in Haiti to detoxifying oil spills. -

Wellesley College Digital Scholarship and Archive

Wellesley College Wellesley College Digital Scholarship and Archive Wellesley Magazine (Alumnae Association) Fall 2016 Wellesley Magazine Fall 2016 Wellesley College Alumnae Association Follow this and additional works at: http://repository.wellesley.edu/wellesleymagazine Recommended Citation Wellesley College Alumnae Association, "Wellesley Magazine Fall 2016" (2016). Wellesley Magazine (Alumnae Association). 20. http://repository.wellesley.edu/wellesleymagazine/20 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by Wellesley College Digital Scholarship and Archive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Wellesley Magazine (Alumnae Association) by an authorized administrator of Wellesley College Digital Scholarship and Archive. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FALL 2016 | A JOYFUL BEGINNING | FOR OUR OLD LADIES | TELL ME A STORY A CALL TO TEACH cover_final.indd 1 10/27/16 12:11 PM LATE-BREAKING NEWS To Our Readers This magazine was on press as U.S. voters went to the polls for the 2016 presidential election. In order to bring you coverage of election night at the College—when several thousand alumnae and the on-campus community gathered to watch the returns and to mark the historic bid for the presidency by Hillary Rodham Clinton ’69—we literally held the presses. It was a night of hope, solidarity, and, later, sadness for many who attended (see page 5). Additional coverage will appear in future issues. PORTRAIT BY JUSTIN SULLIVAN/GETTY IMAGES NEWS/GETTY IMAGES COVER ILLUSTRATION NEWS/GETTY AAD BY GOUDAPPEL, IMAGES PHOTO RICHARD BY HOWARD SULLIVAN/GETTY JUSTIN BY PORTRAIT ifc-pg1_toc_election_final.indd c2 11/14/16 3:44 PM Looking to the Future Dear Wellesley community, For many of us hoping to see our fi rst woman president, this election has surprised and disap- pointed us. -

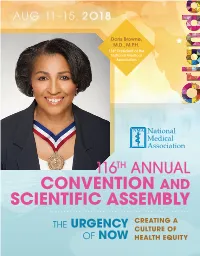

Nma 2018 Con Program Online.Pdf

AU G 11–15 , 2O18 Doris Browne, M.D., M.P.H. 118th President of the National Medical Association 116 TH ANNUAL CONVENTION AND SCIENTIFIC ASSEMBLY THE CREATING A URGENCY CULTURE OF OF NOW HEALTH EQUITY Tiahna Kyle Marjorie here to make a difference. Sickle cell disease (SCD) is the most common rare inherited blood disorder in the United States affecting nearly 100,000 Americans. Greater education and improved treatment options are desperately needed. For 30 years, Pfizer has been a part of the journey with the rare disease community to make a lasting impact through potentially life-changing innovations, trusted partnerships, and unwavering passion. There is only one way we succeed—together. Visit Pfizer.com/RareDisease to learn more. THE URGENCY OF NOW: CREATING A CULTURE OF HEALTH EQUITY 1 A MESSAGE FROM THE PRESIDENT Dear Colleagues, As the 118th President, I am honored and privileged to extend greetings to all attendees of the 116th Annual Convention and Scientific Assembly of the National Medical Association (NMA).This year’s convention theme is The Urgency of Now: Creating a Culture of Health Equity, it brings together the culmination of a year of collaboration with other professional organizations, disease associations, industry, civic organizations, advocacy groups and faith-based organizations to develop a framework for health equity in the African American community. During the convention experts will address many of the health inequity issues facing patients, healthcare providers, communities, and the Nation. There will be ample opportunities to collaborate, network, and dialogue with stakeholders. We will examine research findings that focus on social determinants of health and the needed health policies. -

2018-4-Winter-Webedition.Pdf

For more information or to make a gift, please contact us at: JEFFERSONTRUST.ORG Since 2006, The Je erson Trust has provided more than $7 million to support 179 innovative projects at the University of Virginia. CIVIL WARERA CHARLOTTESVILLE The John L. Nau III Center for Civil War History is working on a pair of new digital projects examining the lives of University of Virginia students and African American men from Albemarle County who served in the Union army or navy. Funding from the Je erson Trust helps complete both projects by hiring undergraduate and graduate research assistants, providing necessary research funds, and creating a project website dedicated to telling the stories of UVA Unionists. Jeerson portrait by Thomas Sully, courtesy of Monticello / The Thomas Jeerson Foundation JeffTrustAd_Winter2018.indd 6 11/8/2018 2:10:27 PM SUPPORTING ’HOOS AT EVERY STAGE OF THEIR LIVES Your gift to the Alumni Association Annual Fund supports nearly $2 million in scholarships that we award to promising students each year. Promoting academic excellence is just one way that we serve our alumni and our University. SUPPORT THE UVA ALUMNI ASSOCIATION ANNUAL FUND GiveToHoos.com 180Years_AnnualFundAd_Winter18-FINAL.indd 1 11/7/2018 2:27:01 PM TIMELESS APPEAL OFF GARTH ROAD AND UNDER 8 MINUTES FROM TOWN STRONG VIEWS ON 13 FARMINGTON ACRES IMMACULATE 157 ACRE WESTERN ALBEMARLE ESTATE - EXCELLENT VIEWS 2210 CAMARGO DRIVE $1,250,000 With exceptional curb appeal and premium construction quality in the Meriwether Lewis district, this 5 bedroom, 4.5 bathroom stone and hardiplank residence built in 2007 by Jacques Homes offers an excellent modern floor plan 2155 DOGWOOD LANE • $5,995,000 including 1st floor master, Sited on one of Farmington’s largest, most beautiful open casual living spaces and parcels, ‘Treetops’ is a center hall Georgian constructed in 2001 to uncompromising standards. -

Vivian Pinn, MD Was the First Full-Time Director of the Office of Research on Women's Health

Bio: Vivian Pinn, MD was the first full-time Director of the Office of Research on Women’s Health (ORWH) from 1991-2011 at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and NIH Associate Director for Research on Women’s Health. Prior to that, she was Professor and Chair of the Department of Pathology at Howard University College of Medicine, Associate Professor of Pathology and Assistant Dean of Student Affairs at Tufts University School of Medicine, and Teaching Fellow at Harvard Medical School. Through the ORWH, she led NIH efforts to implement and monitor the inclusion of women and minorities in clinical research funded by the NIH. More recently, she focused on the importance of sex differences research across the spectrum from cellular to translational research and implementation into health care. Dr. Pinn also co-chaired The NIH Working Group on Women in Biomedical Careers. An Interview with Dr. Vivian Pinn November 14th, 2018 Conducted by IWL Leadership Scholars Leshya Bokka and Anisha Patel, Class of 2020 Leshya Bokka (LB) & Anisha Patel (AP): What were your impressions of women growing up? Vivian Pinn (VP): I came from a family of very strong women, and my mother was the oldest in her family. She was always the responsible one, and I learned very early on that the oldest woman usually has responsibility for their sisters and brothers. Even though I was an only child, I saw that. My father was not the oldest in his family, but he pretty much was the responsible brother in his family. Both of my grandmothers, fortunately, were educated, which was unusual in those days, and I had a number of aunts around me. -

Double Executive Masters in Health Policy from the University of Chicago and the London School of Economics

JOHN C. HEATON Faculty Codirector of Private Wealth Management, Joseph L. Gidwitz Professor of Finance OI CENTENNIAL … ROSANNA WARREN … HOME DECOR EDITOR … HAGEL LECTURE … THINKING HUTS … RETIRING REP GAIN THE FRAMEWORKS TO PRIVATE WEALTH PROTECT AND GROW YOUR WEALTH MANAGEMENT Exclusively for High-Net-Worth There are many roads to growing and protecting Individuals and Families business and financial capital while reinforcing Gleacher Center, Chicago personal values that support a flourishing family. In the October 14–18, 2019 Chicago Booth Private Wealth Management program For more information, visit for high-net-worth individuals and families, you can ChicagoBooth.edu/PWM explore the options and then decide which ones are or call 312.464.8732 to submit an application. right for you and your family. SUMMER 2019 SUMMER SUMMER 2019, VOLUME 111, NUMBER 4 UCH_Summer2019 cover and spine_v7.indd 1 8/1/19 5:08 PM DOUBLE EXECUTIVE MASTERS IN HEALTH POLICY FROM THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO AND THE LONDON SCHOOL OF ECONOMICS 2 CITIES 2 DEGREES 1 PROGRAM YEAR 1 NOVEMBER–DECEMBER 2 weeks in London APRIL–MAY 2 weeks in Chicago SUMMER: Harris Policy Project YEAR 2 NOVEMBER–DECEMBER 2 weeks in London APRIL–MAY 2 weeks in Chicago SPRING: MSc Dissertation SUMMER: LSE Capstone Project Solutions to global health challenges require global thinking. APPLY NOW lse.uchicago.edu/UCmag UCH_ADS_v1.indd 2 8/2/19 10:01 AM EDITORˆS NOTES VOLUME 111, NUMBER 4, SUMMER 2019 EDITOR Laura Demanski, AM’94 SENIOR EDITOR Mary Ruth Yoe ASSOCIATE EDITOR Susie Allen, AB’09 MANAGING EDITOR Rhonda L. Smith ART DIRECTOR Guido Mendez ALUMNI NEWS EDITOR Andrew Peart, AM’16, PHD’18 FERTILE SOIL COPY EDITOR Sam Edsill GRAPHIC DESIGNER Laura Lorenz CONTRIBUTING EDITORS John Easton, AM’77; Carrie Golus, AB’91, AM’93; Brooke E. -

Fifth Annual Vivian W. Pinn Symposium Event Program

5TH ANNUAL VIVIAN W. PINN SYMPOSIUM Integrating Sex and Gender into Biomedical Research as a Path for Better Science and Innovation MAY 11 – 12, 2021 5TH ANNUAL VIVIAN W. PINN SYMPOSIUM: Agenda at a Glance INTEGRATING SEX AND GENDER INTO BIOMEDICAL RESEARCH AS A PATH Overview FOR BETTER SCIENCE AND INNOVATION DAY 1 TUESDAY MAY, 11 DAY 2 WEDNESDAY MAY, 12 9:00 – 10:00 AM Explore Virtual Environment 9:00 – 10:00 AM Explore Virtual Environment Exhibit Hall and Media Room and Booths (Self-Guided) Exhibit Hall and Media Room and Booths (Self-Guided) 10:00 – 10:30 AM Welcome and Opening Remarks 10:00 – 10:15 AM Welcome and Recap of Day 1 The Office of Research on Women’s Health (ORWH) is thrilled to host the 5th Annual Vivian W. Pinn Symposium in Auditorium Auditorium partnership with the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health (FNIH). Convened by ORWH each year, this event honors the first full-time director of the office, Dr. Vivian W. Pinn, in recognition of National Women’s Health Week. In 10:30 – 11:00 AM Keynote Address 10:15 – 11:15 AM Panel: Government Agencies line with ORWH’s mission of putting science to work for the health of women, this event serves as a critical forum for Auditorium Auditorium Call to Action experts across sectors to communicate and collaborate for the advancement of women’s health. This year’s event will focus on illustrating the scientific, societal, and economic opportunities of integrating sex and 11:00 AM – 12:00 PM Panel: Teach 1 Reach 1: 11:15 AM – 12:15 PM Panel: “Putting Skin in the Game”: Auditorium Academia’s Roll Call Auditorium The Economic Opportunity gender into biomedical research and the power of working together.