Jananne Al-Ani Baptist Coelho Shaun Gladwell

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Narelle Autio Deidre Brollo Maria Fernanda Cardoso Julia Ciccarone Shaun Gladwell Helga Groves Jess Macneil Todd Mcmillan Harry

Narelle Autio Deidre Brollo Maria Fernanda Cardoso Julia Ciccarone Shaun Gladwell Helga Groves Jess MacNeil Todd McMillan Harry Nankin Bill Viola Wukun Wanambi curated by Meryl Ryan Where there is water… This exhibition not only there is Lake Macquarie embraces notions of our location City Art Gallery. but, through Meryl Ryan’s thoughtful text and selection As we are nestled on the foreshore of a works by contemporary of this country’s largest coastal artists, takes the theme further saltwater lake, overlooking as a metaphor or narrative to an active marina, it is impossible describe aspects of survival, not to consider water an ongoing human emotion, and the state theme in our programming. of the environment. The changing weather reflected in the lake’s surface each day, Congratulations to all those visitors’ delight in the splendour of involved, in particular Ryan the site, the yachts sailing by, and and the artists for such the deep sense of its Aboriginal mesmerising work. Our sincere significance, always remind thanks also to the gallerists for us of where we are. their invaluable support, and the private collectors for generously making their artworks available to the exhibition. I am sure you will all enjoy the exhibition, as much as, if not more than, you enjoy the site. Debbie Abraham Gallery Director Lake Macquarie City Art Gallery 3.30am Friday 17 January 1986 We have been at sea almost a week But mean-spirited dark The pre-dawn watch on ocean As they coast alongside, invisible Large bodies of water, as we’ve The fickle ocean surface, with its Once below the surface everything Indian Ocean near Chagos now – with only the vast waterscape clouds rolled in with the voyages always delivered in one against the night, their scale and all come to learn, are storehouses restless nature, can distract us changes. -

List of Stakeholders Consulted

APPENDIX C.1 LIST OF STAKEHOLDERS CONSULTED ORGANISATION REPRESENTATIVES PRESENT NOTES PERFORMING ARTS COMMERCIAL THEATRE 1 The Really Useful Company Asia Pacific Tim McFarlane 2 The Gordon Frost Organisation John Frost 3 Disney Theatrical James Thane 4 Andrew Kay & Associates Andrew Kay 5 Ensemble Theatre Sandra Bates Phone consulation CONTEMPORARY MUSIC 6 Chugg Entertainment Michael Chugg 7 Michael Coppel Presents Michael Coppel SUBSIDISED COMPANIES 8 Bangarra Dance Theatre Catherine Baldwin / Aaron Beach 9 Sydney Theatre Company Patrick McIntyre / Jo Dyer 10 Australian Ballet Valerie Wilder 11 Opera Australia Adrian Collette / Chris Yates 12 Sydney Symphony Rory Jeffes 13 Belvoir Street Theatre Ralph Myers / Brenna Hobson 14 Australian Chamber Orchestra Tim Calnin 15 Bell Shakespeare Chris Tooher Mary Jo Capps / Timothy Matthies / Marcus 16 Musica Viva Hodgson 17 Australian Theatre for Young People Fraser Corfield / Moira Hay 18 Darlinghurst Theatre Glenn Terry 19 Darlinghurst Venues / Indie Producers Forum Old Fitzroy / Tamarama Rock Surfers Leland Keen Group consult SWS Stables / Griffin Sam Strong Group consult Arts Radar Kate Armstrong Group consult 20 Music Companies forum Song Company Karen Baker Group consult Sydney Philharmonia Choirs Lisa Nolan Group consult Sydney Youth Orchestra Antony Ernst Group consult Taikoz/Synergy David Sidebottom Group consult Gondwana Choirs Alexandra Cameron-Fraser Group consult 21 Australian Brandenburg Orchestra Bridget O'Brien 22 Ausdance NSW Cathy Murdoch 23 Legs on the Wall Grant O’Neill OUTDOOR -

8082 AUS VB07 ENG Edu Kit FA.Indd

Venice Biennale 2007 Australia 10 June – 21 November 2007 Education Resource Kit Susan Norrie HAVOC 2007 Daniel von Sturmer The Object of Things 2007 Callum Morton Valhalla 2007 Contents Education resource kit outline Australians at the Venice Biennale Acknowledgements Why is the Venice Biennale important for Australian arts? Australia’s past participation in the Venice Biennale PART A The Venice Biennale and the Australian presentation Introduction Timeline: The Venice Biennale, a not so short history The Venice Biennale:La Biennale di Venezia Selected Resources Who what where when and why The Venice Biennale 2007 PART B Au3: 3 artists, 3 projects, 3 sites The exhibition Artists in profile National presentations Susan Norrie Collateral events Daniel von Sturmer Robert Storr, Director, Venice Biennale Callum Morton 2007 Map: Au3 Australian artists locations Curators statement: Thoughts on the at the Venice Biennale 2007 52nd International Art Exhibition Colour images Introducing the artist Au3: the Australian presentation 2007 Biography Foreword Representation Au3: 3 artists, 3 projects, 3 sites Collections Susan Norrie Quotes Daniel von Sturmer Commentary Callum Morton Years 9-12 Activities Other Participating Australian Artists Key words Rosemary Laing Shaun Gladwell Christian Capurro Curatorial Commentary: Au3 participating artists AU3 Venice Biennale 2007 Education Kit Australia Council for the Arts 3 Education Resource Kit outline This education resource kit highlights key artworks, ideas and themes of Au3: the 3 artists, their 3 projects which are presented for the first time at 3 different sites that make up the exhibition of Australian artists at the Venice Biennale 10 June to 21 November 2007. It aims to provide a entry point and context for using the Venice Biennale and the Au3 exhibition and artworks as a resource for Years 9-12 education audiences, studying Visual Arts within Australian High Schools. -

SHAUN GLADWELL B. 1972, Sydney Australia

WWW.TRISHCLARK.CO.NZ 1 BOWEN AVENUE T +64 9 379 9556 AUCKLAND 1010 C +64 21 378 940 NEW ZEALAND [email protected] SHAUN GLADWELL b. 1972, Sydney Australia. EDUCATION 2002 Associate Research, Goldsmiths College, University of London, UK 2001 Master of Fine Art (research), College of Fine Arts, University of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia 1996 Bachelor of Fine Arts (First Class Honours), Sydney College of the Arts, Australia SELECTED PUBLIC AND PRIVATE COLLECTIONS National Gallery of Australia Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney, Australia Art Bank, Australia Campbelltown Arts Centre, Sydney, Australia The City of Sydney, Australia Macquarie Bank University of Technology, Sydney, Australia The University of Sydney, Australia University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, Australia Art Gallery of South Australia Govett-Brewster Art Gallery, New Plymouth, New Zealand Museum of Contemporary Art, Tokyo, Japan SCHUNCK, Heerlen, The Netherlands The Progressive Art Collection, USA VideoBrasil, Brazil JUT Foundation For Arts and Architecture, Taiwan Wadsworth Atheneun, USA Orange County Museum of Art, USA AWARDS, HONOURS, SCHOLARSHIPS, COMMISSIONS & APPOINTMENTS 2012 New Work Grant, Australia Council for the Arts 2010 AIR Antwerpen, Residency New Work Grant, Australia Council for the Arts WWW.TRISHCLARK.CO.NZ 1 BOWEN AVENUE T +64 9 379 9556 AUCKLAND 1010 C +64 21 378 940 NEW ZEALAND [email protected] 2007 Australian Film Commission, Travel Grant -

GLADWELL, Shaun 2013

SHAUN GLADWELL 1972 Born Sydney, Australia EDUCATION 2002 Associate Research, Goldsmiths College, University of London, UK 2001 Master of Fine Art (Research), College of Fine Arts, University of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia 1996 Bachelor of Fine Arts (Honours First Class), Sydney College of the Arts, Australia SELECTED SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2013 Morning of the Earth, Anna Schwartz Gallery, Melbourne, Australia Cosmos unfolding in the foot locker/hurt locker, Season Projects, London, UK Fliegende Holländer (!e Flying Dutchman), performed by the Ro"erdam Philharmonic, conducted by Yannick Nézet-Séguin, with video art by Shaun Gladwell Cycles of Radical Will, De La Warr Pavilion, UK Shaun Gladwell: Afghanistan, Australian Embassy, Washington, USA C.O.R.W., screening, Museum of Contemporary Art, Zagreb, Croatia 2012–13 Shaun Gladwell: Afghanistan, Australian War Memorial touring exhibition: Cairns Regional Gallery; Artspace Mackay; Lismore Regional Gallery; Queensland University of Technology Art Museum; Casula Powerhouse, Australia; Launceston Academy Gallery, University of Tasmania, Australia 2012 Broken Dance (Beatboxed), Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia 2011 Riding with Death: Redux, Anna Schwartz Gallery, Sydney, Australia Perpetual 360° Sessions, SCHUNCK*, Heerlen, !e Netherlands Shaun Gladwell: Matrix 162, Matrix Exhibition series, Wadsworth Atheneum, Connecticut, USA Stereo Sequences, Australian Centre for the Moving Image, Melbourne, Australia 2010 Portrait of a man: alive and spinning/Dead as a skeleton dressed -

Australia 53Rd International Art Exhibition LA BIENNALE DI VENEZIA LA BIENNALE DI VENEZIA 1

Australia 53rd International Art Exhibition LA BIENNALE DI VENEZIA LA BIENNALE DI VENEZIA 1 Commissioner’s Foreword When Shaun Gladwell returned from dealing with reflections that are personal, from a range of sources – government, western New South Wales in early 2009 cultural and environmental. corporate, individual and philanthropic – he had accumulated images that were to where none sits as mutually exclusive from Claire Healy and Sean Cordeiro’s massive signal an extension to his work that was the other, conspicuous in its commitment. installation consumes the chapel of the included in the exhibition Think with the Ludoteca – its monumentalism and its I gratefully acknowledge the generous Senses – Feel with the Mind at the Venice stillness are like a memento mori as it assistance of our many public and private Biennale 2007. For Venice 2009 Shaun alludes to transience and impermanence. funding partners. I also warmly thank the is our artist for the Australian Pavilion. Vernon Ah Kee’s work represents themes artists, Tania Doropoulos (project manager Shaun’s involvement with the landscape of contemporary social and cultural politics, for Shaun Gladwell) and Felicity Fenner – and urban spaces – holds recognition of of Indigenous exclusion. But here the modern (curator for Once Removed) for their dedication the sense of place we Australians have in the representation of this exclusion is explored and commitment to presenting Australia’s history of our nation’s art. But his inquiring through long-standing emblematic symbols exhibitions at the Venice Biennale 2009. temperament and his keen interest in the that are representative of white Australian Doug Hall AM role of the culture of his own generation culture. -

MCA Unveils 2018 Exhibition Program Download

MCA PROGRAMMCA ���8 John Mawurndjul, Nawarra- mulmul (Shooting star spirit), 1988, ochres and synthetic polymer on bark, Museum of Contemporary Art Australia, purchased with funds donat- ed by Mr and Mrs Jim Bain, 1989, © John Mawurndjul, licensed by Viscopy 2017 MCA PROGRAM ���8 MEDIA CONTACT: Myriam Conrie 02 9245 2434 / 0429 572 869 [email protected] Click here for media images The Museum of Contemporary Art Australia (MCA) unveils its 2018 program. 2018 Exhibitions MCA Director Elizabeth Ann Macgregor OBE said: ‘2018 is shaping up to be one of TODAY TOMORROW the MCA’s most exciting and diverse years in terms of programming, with works by YESTERDAY:MCA COLLECTION: exceptional Australian and international contemporary artists at all stages of their Ongoing careers, and in varied media.’ PIPILOTTI RIST: SIP MY OCEAN ‘We look forward to engaging a wide range of audiences with art that transcends 1 Nov 2017 – 18 Feb 2018 everyday reality, fires up our imagination and draws us in, but that also gives us the opportunity to be challenged, look at things differently and address difficult issues,’ WORD: MCA COLLECTION Macgregor continued. 4 Dec 2017 – 18 Feb 2018 JON CAMPBELL: MCA COLLECTION A highlight of the program is the first major survey of works by John Mawurndjul, 4 Dec 2017 – 25 Feb 2018 one of Australia’s most important artists. Developed and co-presented by the MCA and 21ST BIENNALE OF SYDNEY the Art Gallery of South Australia, in association with Maningrida Arts & Culture, the 16 Mar – 11 Jun 2018 exhibition will span the thirty years the artist has been making work (from 6 July). -

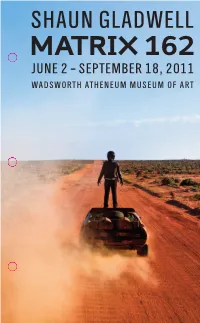

MATRIX 162 —SAUL BELLOW1 Destruction and Deforestation of the Land in the Name of Progress

SHAUN GLADWELL, INTERCEPTOR SURF SEQUENCE, 2009. SHAUN GLADWELL, INTERCEPTOR SURF SEQUENCE, 2009. SHAUN GLADWELL, APOLOGIES 1 – 6, 2007–09. PRODUCTION STILL. PHOTO: JOSH RAYMOND. PRODUCTION STILL. PHOTO: JOSH RAYMOND. PRODUCTION STILL. PHOTO: JOSH RAYMOND. © SHAUN GLADWELL. COURTESY THE ARTIST & © SHAUN GLADWELL. COURTESY THE ARTIST & © SHAUN GLADWELL. COURTESY THE ARTIST & SHAUN GLADWELL ON GRAVITYAND LEVITY ANNA SCHWARTZ GALLERY, AUSTRALIA ANNA SCHWARTZ GALLERY, AUSTRALIA ANNA SCHWARTZ GALLERY, AUSTRALIA The body is subject to the forces of gravity. But the soul is ruled by levity, pure. Gladwell’s Apologies refers most strongly to contemporary Australian issues—the MATRIX 162 —SAUL BELLOW1 destruction and deforestation of the land in the name of progress. Even more, through interaction with the kangaroo, Gladwell symbolically apologizes to the indigenous Ominous and dreamlike, a black car silently crawls along a red dirt road that bisects peoples of Australia who were mistreated under colonization. From the late nineteenth JUNE 2 – SEPTEMBER 18, 2011 the wide open plain of a scrubby desert landscape. A vast blue sky completes the century to the early 1970s, the “Stolen Generation” or “Stolen Children” were forcibly symmetrical composition. The vehicle, viewed from behind at a constant distance, removed from their Aboriginal and Torres Strait Island families to be raised by people WADSWORTH ATHENEUM MUSEUM OF ART raises dust from its tires in slow motion as the car drives endlessly, but goes nowhere. from government agencies and church missions. An official apology was given by the From a car window, an anonymous dark-helmeted figure emerges. The form, clad in government in 2008.8 Such injustices find an American counterpart in long-term black leather, methodically climbs atop the roof of the moving car and stands, back to mistreatment of its own Native American populations. -

Shaun Gladwell the Lacrima Chair La Chaise Lacrima

Shaun Gladwell The Lacrima Chair La Chaise Lacrima Collection+ Shaun Gladwell Sherman Contemporary Art Foundation Shaun Gladwell The Lacrima Chair A multifaceted work comprising: – 6 March sculpture 25 April video 2015 mist screen literary work. Commissioned by Sherman Contemporary Art Foundation Sydney SCAF Project 24 Collection+ Shaun Gladwell An exhibition drawn from the Gene & Brian Sherman Collection and private and public art collections worldwide. Curated by Dr Barbara Polla and Prof. Paul Ardenne Presented at UNSW Galleries SCAF Project 25 La Chaise Lacrima Une nouvelle œuvre aux multiples facettes: 6 Mars sculpture – 25 Avril vidéo 2015 écran de brume œuvre littéraire Commandée par Sherman Contemporary Art Foundation Sydney SCAF Project 24 Collection+ Shaun Gladwell Une exposition issue de la Collection Gene & Brian Sherman et de collections d’art privées et publiques à travers le monde. Organisée par les commissaires de l’exposition Barbara Polla et Paul Ardenne Présentée à UNSW Galleries SCAF Project 25 Contents 3 Shaun Gladwell Table des matières The Lacrima Chair Sherman Contemporary Art Foundation Sydney Preface 5 Shaun Gladwell Gene Sherman Préface Introduction 11 Felicity Fenner Introduction The Lacrima Chair The Lacrima Chair 16 Working Images La Chaise Lacrima La Chaise LacrimaDoppelgänger 49 Barbara Polla Doppelgänger Corpopoetic Gestures 95 Paul Ardenne Gestes corpopoétiques Collection+ Collection+ List of Works 161 Shaun Gladwell Collection+ liste des œuvres Artist Selected Biography 162 Biographie sélective de l’artiste Artist Selected Bibliography 167 Bibliographie sélective de l’artiste Contributors 170 Contributeurs Acknowledgements 173 Remerciements Sherman Contemporary Art Foundation Preface 5 Gene Sherman Chairman and Executive Director Sherman Contemporary Art Foundation Préface My connection with Shaun Gladwell goes back to his undergraduate days: 1997 to be exact. -

Shaun Gladwell Biography

ANNA SCHWARTZ GALLERY SHAUN GLADWELL BIOGRAPHY 1972 Born Sydney, Australia Lives and works in Sydney, Australia EDUCATION 1996 Bachelor of Fine Arts (Honours First Class), Sydney College of the Arts, Sydney 2001 Masters of Fine Art (Research), College of Fine Arts, University of New South Wales, Sydney SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2019 Shaun Gladwell: Pacific Undertow, Museum of Contemporary Art Australia, Sydney 2017 1000 Horses, Tel Aviv Museum of Art, Israel Orbital Vanitas screening, International Film Festival, Cleveland Orbital Vanitas screening, Melbourne International Film Festival, Melbourne Orbital Vanitas screening, Future Film Festival, Bologna, Italy Orbital Vanitas screening, Festival de Cannes, Cannes, France Orbital Vanitas screening, Sundance Film Festival, Park City, Utah, USA Shaun Gladwell: Reverse Readymade, screening, Head On Photo Festival 2017, University of New South Wales Art & Design, Sydney Shaun Gladwell. Skaters versus Minimalismo, Centro Atlantico de Arte Moderno CAAM, Las Palmas, Gran Canaria Shaun Gladwell, Virtual Imperator – Edge of Empire, Australian Centre for Photography, Pop-Up Gallery, Sydney 2016 The Devil Has No Helmet, Analix Forever, Geneva 2015 The Inspector of Tides, Anna Schwartz Gallery, Sydney The Lacrima Chair, Sherman Contemporary Art Foundation, Sydney Collection +: Shaun Gladwell, UNSW Galleries, UNSW Art and Design, Sydney 2014 Shaun Gladwell: BMX Channel, Mark Moore Gallery, California Shaun Gladwell: Field Recordings, Samstag Museum, University of South Australia, Adelaide 2013 Director, Family, -

Shaun Gladwell: Stereo Sequences

FOREWORD As Australia’s leading centre for screen and digital culture, the Australian Centre for the Moving Image (ACMI) is committed to supporting and exhibiting the work of the world’s most significant moving image makers. In recent years ACMI has presented major exhibitions by seminal practitioners such as Tim Burton, Dennis Hopper, Stanley Kubrick, Len Lye, Christian Marclay and Bill Viola. ACMI also has a long tradition of collecting and commissioning works. We currently hold more than 650 works by major inter- DIRECTOR’S DIRECTOR’S national artists – László Moholy-Nagy, Nam June Paik, Johan Grimonprez and Anthony McCall among them. The ACMI Collection also features a substantial catalogue of works by Australian artists, including Daniel Crooks, Destiny Deacon, Tracey Moffatt, Daniel von Sturmer, Lynette Wallworth and others. Horizons: The ACMI Commissions Series continues this tradition with ACMI’s most significant commission of works by a single artist to date: Shaun Gladwell: Stereo Sequences. Over the last decade Shaun Gladwell has emerged as one of Australia’s most exciting and acclaimed video artists and pre- eminent champion of moving image culture. His evocative work using large-scale video installations, photography and sculpture offers unique interpretations and a deeply personal vision of Australia’s landscapes, myths and cultural identity. From his breakout video Storm Sequence (2000) to his installation MADDESTMAXIMVS: Planet and Stars Sequence at the 2009 Venice Biennale, Gladwell has created ambitious video and moving image installations that are poetic meditations on the nature and possibilities of the art form. ACMI has been thrilled to work with Shaun on this exciting project. -

16Th Biennale of Sydney Report

16 TH TH BIENNALE OF SYDNEY BIENNALE OF SYDNEY 16 BIENNALE OF SYDNEY REPORT WWW. B IENNALEOF S 17TH BIENNALE OF SYDNEY YDNEY.CO 16TH BIENNALE OF SYDNEY 12 MAy – 1 AUGUST 2010 www.biennaleofsydney.com.au17TH BIENNALE OF SYDNEY REPORT M 12 MAy – 1 AUGUST 2010 .AU www.biennaleofsydney.com.au 2008 PARTNERS GOVERNMENT PARTNERS The Biennale of Sydney is supported by the Visual The Biennale of Sydney is assisted by the Australian Government The Biennale of Sydney is assisted by the NSW Government through Arts and Craft Strategy, an initiative of the Australian, through the Australia Council, its arts funding and advisory body. Arts NSW. We gratefully acknowledge the assistance of Arts NSW state and territory governments. through the NSW Government Exhibitions Indemnication Scheme. FOUNDING PARTNER MAJOR VENUE PARTNERS EXHIBITION PARTNERS SINCE 1973 MAJOR PARTNERS ACCOMMODATION NEWSPAPER PARTNER PARTNER DIGITAL MEDIA PARTNER PARTNERS SUPPORTERS ARTS MEDIA PARTNER PUBLIC PROGRAM PARTNERS DONORS PUBLIC PROGRAM AND EDUCATION SUPPORTERS ARTISTS’ PARTY SUPPORTERS 2 2008 BIENNALE OF SYDNEY REPORT 2008 BIENNALE OF SYDNEY REPORT 2008 PARTNERS GOVERNMENT PARTNERS The Biennale of Sydney is supported by the Visual The Biennale of Sydney is assisted by the Australian Government The Biennale of Sydney is assisted by the NSW Government through Arts and Craft Strategy, an initiative of the Australian, through the Australia Council, its arts funding and advisory body. Arts NSW. We gratefully acknowledge the assistance of Arts NSW state and territory governments.