Alaris Capture Pro Software

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual of Medieval Studies at Ceu Vol

ANNUAL OF MEDIEVAL STUDIES AT CEU AT STUDIES MEDIEVAL OF ANNUAL 24 2018 VOL. The Annual of Medieval Studies at CEU, more than any comparable annual, accomplishes the two-fold task of simultaneously publishing important scholarship and informing the wider community of the ANNUAL breadth of intellectual activities of the Department of Medieval Studies. And what a breadth it is: Across the years, to the core focus OF MEDIEVAL STUDIES on medieval Central Europe have been added the entire range from AT CEU Late Antiquity till the Early Modern Period, the intellectual history of the Eastern Mediterranean, Asian history, and cultural heritage studies. I look forward each summer to receiving my copy. vol. 24 2018 Patrick J. Geary Central European University Department of Medieval Studies Budapest Volumes of the Annual are available online at: http://www.library.ceu.hu/ams/ ANNUAL OF MEDIEVAL STUDIES AT CEU VOL. 24 2018 Central European University Budapest ANNUAL OF MEDIEVAL STUDIES AT CEU VOL. 24 2018 Edited by Gerhard Jaritz, Kyra Lyublyanovics, Ágnes Drosztmér Central European University Budapest Department of Medieval Studies All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means without the permission of the publisher. Editorial Board Gerhard Jaritz, György Geréby, Gábor Klaniczay, József Laszlovszky, Judith A. Rasson, Marianne Sághy, Katalin Szende, Daniel Ziemann Editors Gerhard Jaritz, Kyra Lyublyanovics, Ágnes Drosztmér Proofreading Stephen Pow Cover Illustration The Judgment of Paris, ivory comb, verso, Northern France, 1530–50. London, Victoria and Albert Museum, inv. no. 468-1869. -

Jeremy Montagu Some Mss. in the British Library with Instruments Page 1 of 2

Jeremy Montagu Some Mss. In the British Library with Instruments Page 1 of 2 Some Manuscripts in the British Library with Illustrations of Musical Instruments and a few other sources that I have found FoMRHIQ 2, January 1976,Comm. 8 Arundel 83. Conflation of two English Psalters, East Anglia, c.1310. The second half is known as the de Lisle Psalter. Good source. Includes: long trumpets, harps, citole, bagpipe, bells, fiddle, portative, psaltery, duct flute, pipe & tabor. Cotton, Tib.C.vi. Psalter, mid 11th c. f.30 is well-known; the rest is the usual Boethius improbabilities of the period. Egerton 1139. Queen Melissander’s Psalter, Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem, c.1140. The only instrument is a good harp, available asa postcard. The ivory cover is well known: King David playing what might be a dulcimer. Harley 2804. German Bible, 1148. f.3 has a not very good David and musicians. Harley 4425. La Roman de la Rose, pre-1500. 2 folios with music parties. Royal 2.A.xvi. Psalter time of Henry VIII, with annotations by him. Harp, pipe& tabor, short trumpet, dulcimer. Interesting that Henry is one of the musicians (and his fool shuts his ears to avoid his playing). Royal 2.A.xxii. The Westminster Psalter, late 12th c. David with harp and bells (postcard available), another harp. Interesting in that Westminster Abbey has a very similar hemi- spherical bell in the Undercroft exhibition room. Royal 2.B.vii. The Queen Mary Psalter, English early 14th c. well known source with a lot of material, but none quite as good and clear as in other East Anglian psalters (e.g. -

A Reappraisal of the Bedford Hours

A REAPPRAISAL OF THE BEDFORD HOURS JANET BACKHOUSE ALREADY well known to bibliophiles at the time of its purchase in February 1852, the Bedford Hours has ever since been justifiably regarded as one ofthe star attractions ofthe national collection.^ Some of its illustrations, especially the lively miniatures of Noah's Ark, have become famous through frequent reproduction in popular art and history books and on greetings cards. Individual pages are often included in more serious studies of late medieval illumination because this manuscript, together with the Duke of Bedford's Breviary in Paris,^ has given a name—the Bedford Master—to one ofthe leading book painters, otherwise anonymous, of the early fifteenth century. It therefore comes as something of a shock to find that only once, as long ago as 1794, has the Bedford Hours been the subject of a full-scale published description-* and that discussions devoted specifically to it are equally rare."'" The enormous range ofthe book's pictorial scheme, which includes thirty-eight large miniatures and almost 1,250 tiny marginal illustrations, each little more than an inch in diameter, is perhaps sufficiently daunting to account for this reticence. The present article will make no attempt to provide a detailed description of the miniatures, though an outline of their contents is included in the description of the manuscript's structure which is printed at the end. Its chief concern is to put forward a suggested explanation ofthe over-all design ofthe Bedford Hours and to look again at the traditional view that the manuscript was ordered by John of Lancaster, Duke of Bedford, asagifttohisbride Anne of Burgundy, sister of Duke Philip the Good, at the time of their marriage in 1423. -

Adapting the Hellmouth in the Office of the Dead Omfr the Hours of Catherine of Cleves: an Experiment in Using a Dramaturgical Approach to Medieval Studies

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Masters Theses Dissertations and Theses July 2021 Adapting the Hellmouth in the Office of the Dead omfr the Hours of Catherine of Cleves: An Experiment in Using a Dramaturgical Approach to Medieval Studies Tatiana A. Godfrey University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/masters_theses_2 Part of the Acting Commons, Ancient, Medieval, Renaissance and Baroque Art and Architecture Commons, Film Production Commons, Other Theatre and Performance Studies Commons, Performance Studies Commons, Screenwriting Commons, and the Theatre History Commons Recommended Citation Godfrey, Tatiana A., "Adapting the Hellmouth in the Office of the Dead omfr the Hours of Catherine of Cleves: An Experiment in Using a Dramaturgical Approach to Medieval Studies" (2021). Masters Theses. 1049. https://doi.org/10.7275/22868967.0 https://scholarworks.umass.edu/masters_theses_2/1049 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations and Theses at ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Masters Theses Dissertations and Theses Adapting the Hellmouth in the Office of the Dead omfr the Hours of Catherine of Cleves: An Experiment in Using a Dramaturgical Approach to Medieval Studies Tatiana -

No. 16, September 2015

anuscripts on my mind News from the Vatican Film Library No. 16 September 2015 ❧ Editor’s Remarks ❧ Exhibitions ❧ News and Postings ❧ Conferences and Symposia ❧ New Publications ❧ Editor’s Remarks ear colleagues and manuscript lovers: I hope all your semesters are beginning with a bang, after a summer that zipped by practically without notice. I am happy to say that we have a very full issue 16; it was tricky getting everything Dto fit, and you will notice some fairly squashed-together pages. I open here with some Vatican Film Library topics, the first of which is a Call for Papers for next year’s conference. 43rd Saint Louis Conference on Manuscript Studies, October 14–15, 2016 Call for Papers The Keynote Speaker will be Madeline H. Caviness, Mary Richard- Manuscripts for Travelers: Directions, Descriptions, and Maps son Professor Emeritus, Tufts University, who will speak on “Medi- This session focuses on manuscripts of travel and accounts of plac- eval German Law and the Jews: the Sachsenspiegel Picture-Books.” es and geographies intended for practical use: perhaps as guid- I invite you to submit paper proposals for the sessions below. This ance for a journey; descriptions of topography and marvels, or as year we have an online submission form to make the process eas- travel accounts of pilgrimage, mission, exploration, and commer- ier: http://lib.slu.edu/special-collections/programs/conference. cial or diplomatic expeditions. They could constitute itineraries, guidebooks, narratives, surveys, chorographies, or practical maps Patterns of Exchange: Cross-Cultural Practice and Production such as city plans, local maps, or portolan charts. -

Revised-Office of the Dead in English Books of Hours

?41 ;225/1 ;2 ?41 01-0 59 1937-90+ 58-31 -90 8@>5/ 59 ?41 .;;6 ;2 4;@=> -90 =17-?10 ?1A?>! /# &')%"/# &)%% >BQBI >DIFLL - ?IFRJR >TCMJSSFE GOQ SIF 0FHQFF OG <I0 BS SIF @NJUFQRJSX OG >S# -NEQFVR '%&& 2TLL MFSBEBSB GOQ SIJR JSFM JR BUBJLBCLF JN =FRFBQDI,>S-NEQFVR+2TLL?FWS BS+ ISSP+$$QFRFBQDI"QFPORJSOQX#RS"BNEQFVR#BD#TK$ <LFBRF TRF SIJR JEFNSJGJFQ SO DJSF OQ LJNK SO SIJR JSFM+ ISSP+$$IEL#IBNELF#NFS$&%%'($'&%* ?IJR JSFM JR PQOSFDSFE CX OQJHJNBL DOPXQJHIS THE OFFICE OF THE DEAD IN ENGLAND: IMAGE AND MUSIC IN THE BOOK OF HOURS AND RELATED TEXTS, C. 1250- C. 1500 SARAH SCHELL SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY SCHOOL OF ART HISTORY, UNIVERSITY OF ST ANDREWS DECEMBER, 2009 1 ABSTRACT This study examines the illustrations that appear at the Office of the Dead in English Books of Hours, and seeks to understand how text and image work together in this thriving culture of commemoration to say something about how the English understood and thought about death in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. The Office of the Dead would have been one of the most familiar liturgical rituals in the medieval period, and was recited almost without ceasing at family funerals, gild commemorations, yearly minds, and chantry chapel services. The Placebo and Dirige were texts that many people knew through this constant exposure, and would have been more widely known than other 'death' texts such as the Ars Moriendi. The images that are found in these books reflect wider trends in the piety and devotional practice of the time. -

Anuscripts on My Mind

anuscripts on my mind News from the No. 24 May 2018 ❧ Editor’s Remarks ❧ Exhibitions ❧ Queries and Musings ❧ Conferences and Symposia ❧ New Publications, etc. ❧ Editor’s Remarks ear colleagues and manuscript lovers: May greetings and glimpses of spring: Dr. Christine Jakobi-Mirwald sent an atmospheric portrait of St. Georg Oberzell amidst greenhouses on the Reichenau, and a profusion of Dnew blooms down by the lake at Lindau. She also brings to our attention a much-await- ed conference on Canon Tables in Hamburg, an update on scholarship following Carl Norden- falk's ground-breaking 1938 publication. It will take place 16–18 May; register and download the program and abstracts at: https://www.manuscript-cultures.uni-ham- burg.de/register_canon2018.html Here’s a call for papers for the Mid-America Medieval Association annual conference with a fabulous theme; apply quickly! deadline is June 1! https://anzamems.org/?p=9014 The biggest news for next month is the maiden voyage of the Saint Louis Conference on Manuscript Studies in its new venue and month: now embedded in the Annual Symposium on Medieval and Renaissance Studies held in June at Saint Louis Univer- sity, this year on 18–20 June 2018. The 45th Annual Saint Louis Conference on Manuscript Studies will be held on all three days in the beautiful Père Marquette conference room, featuring eight sessions and its own plenary lecture. You can access the Sym- posium program on the Symposium website at http://smrs.slu.edu/schedule.html; (the manuscript conference sessions head the time slots); although all attendees will find a printed general program in their registration packets, there will be a separate program for the manuscript conference distributed on site in Père Marquette. -

Abstract Resumo

Abstract Because of the distance in time and the lack of testifying documents, one should be key-words extremely careful when labelling portraits in medieval books of hours as donor por- traits or owner portraits. There are, however, manuscripts that reveal their fi rst owner french art fifteenth century within their decorative programme, and the Lamoignon Hours (Lisbon, Gulbenkian, illumination ms LA 237) is one of these. This article aims to discuss the iconography of the three books of hours portraits found on f.165v, f.202v and f.286v, as well as the relevance of portraiture heraldry and heraldic insignia in books of hours and the signifi cance of such content to the original owner and to those who possessed the book afterwards. • Resumo A distância no tempo e a ausência de documentação testemunhal obrigam a agir com palavras-chave cautela quando se pretende confi rmar a representação dos donos ou dos doadores nos retratos dos Livros de Horas medievais. Existem, porém, alguns manuscritos arte francesa século xv que revelam no seu programa decorativo a identidade do seu primeiro proprietário, iluminura como acontece nas Horas de Lamoignon (Lisboa, Museu da Fundação Calouste livro de horas Gulbenkian, ms LA 237). O presente artigo explora a iconografi a dos três retratos heráldica que aparecem em f.165v, f.202v e f.286v, e analisa a relevância do retrato e dos emblemas heráldicos nos Livros de Horas, bem como a importância deste tipo de conteúdo para o dono original e para os possuidores posteriores do livro. • Agradecimentos por ajuda na confi guração do texto e sugestões de Ana Catarina Sousa, Pedro Fialho de Sousa, Justino Maciel, Felix Teichner e Heidi. -

Of Christian Art Book List (01/27/2014) Shelf Author Title No

INDEX OF CHRISTIAN ART BOOK LIST (01/27/2014) SHELF AUTHOR TITLE NO. (The) Art Bulletin, Vol. XXXII, No. 4, to Charles Rufus Morey from his former students, January 27, 1951 SR-11E (The) Books Called the Apocrypha V5 (The) Catholic Encyclopedia, 15 volumes, Vols. I - XV and index (1907) Vols. I - VIII SR-14C (The) Catholic Encyclopedia, 15 volumes, Vols. I - XV and index (1907) (cont'd) Vols. IX - XV (Vol. 9 is from library) SR-14D (The) Hebrew-English Old Testament from the Bagster Polyglot Bible V6 (The) Holy Metropolis of Corfu Byzantine and Post-Byzantine Art in Corfu: Monuments, Icons, Treasures, Culture (1994) LD-2A (The) Holy Scriptures of the Old Testament: Hebrew and English V6 (The) Hunt Museum: Essential Guide AA2 (The) Israel Museum, Jerusalem Israel Museum Studies in Archaeology SR-2B (The) Jewish Encyclopedia, 12 volumes, Vols. I - XII Vols. I - VIII SR-14A (The) Jewish Encyclopedia, 12 volumes, Vols. I - XII (cont'd) Vols. IX - XII SR-14A (The) Kaufmann Haggadah SR-2B (The) New Jerusalem Bible V3 (The) New Testament of our Lord and Saviour Jesus Christ V3 (The) Oxford Companion to Christian Art and Architecture SR-1B (The) Sarum Missal in English T3 (The) Septuagint Version of the Old Testament With an English Translation and with Various Readings and Critical Notes V4 (The) Zondervan Parallel New Testament in Greek and English V4 900 Jahre Stift Gottweig 1083-1983, Ein donaustift als reprasentant benediktinischer kultur SR-2F Aartsbisschoppelijk Museum Utrecht Beeldhouwkunst SR-4B Aartsbisschoppelijk Museum Utrecht KoptischeSammlung des Ikonen-museums 26 Oktober - 25 November 1962 SR-4B Abad Zapatero, J. -

Mediaeval Art and Architecture. the Library of Ronald R. Atkins

MEDIAEVAL ART AND ARCHITECTURE 2503 titles in ca. 2800 volumes ARS LIBRI 2 MEDIAEVAL ART & ARCHITECTURE GENERAL WORKS 1 AACHEN. RATHAUS. Karl der Grosse: Werk und Wirkung. June-Sept. 1965. Preface by Wolfgang Braunfels. (10th Council of Europe Exhibition.) xl, 567, (1)pp., 166 plates (8 color), 4 folding maps. Stout 4to. New cloth (orig. wraps. bound in). From the library of Hugo Buchthal. Aachen, 1965. Arntzen/Rainwater R21 2 ABBOTT, DEAN ERIC, ET AL. Westminster Abbey. [By] Dean Eric Abbott, John Betjeman, Kenneth Clark, John Pope- Hennessy, A.L. Rowse, George Zarnecki. 264pp. Prof. illus. Folio. Cloth, 1/4 leather. Radnor (The Annenberg School Press), 1972. 3 ABGARYAN, G.V. The Matenadaran. 46, (4)pp., 18 color plates. Text illus. Lrg. 8vo. Cloth. Erevan (Armenian State Publishing House.), 1962. 4 ABOU-EL-HAJ, BARBARA. The Medieval Cult of Saints: Formations and Transformations. xviii, 456, (1)pp. 206 illus. Sm. 4to. Cloth. D.j. Cambridge (Cambridge University Press), 1994. 5 ABULAFIA, DAVID. Frederick II: A Medieval Emperor. xvi, 466pp. 10 illus., 4 maps. Wraps. New York/Oxford (Oxford University Press), 1988. 6 ACHEIMASTOU-POTAMIANOU, MYRTALE. Greek Art: Byzantine Wall-Paintings. 272pp. 190 color illus. 4to. Cloth. D.j. Athens (Ekdotike Athenon), 1994. 7 ADAIR, JOHN. The Pilgrim’s Way: Shrines and Saints in Britain and Ireland. 208pp. 199 illus (20 color), 2 maps. 4to. Cloth. D.j. London (Thames and Hudson), 1978. 8 ADAMS, HENRY. Mont-Saint-Michel and Chartres. With an introduction by Ralph Adams Cram. xiv, 401, (1)pp. Frontis. in color, 12 plates. 4to. Boards, 1/4 cloth. -

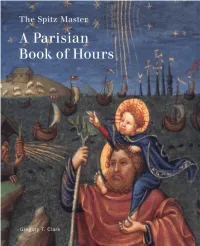

The Spitz Master: a Parisian Book of Hours

The Spitz Master A Parisian Book of Hours The Spitz Master A Parisian Book of Hours Gregory T. Clark GETTY MUSEUM STUDIES ON ART Los Angeles For Nicole Reynaud and François Avril © 2003 J. Paul Getty Trust Cover: Spitz Master (French, act. ca. 1415-25). Saint Getty Publications Christopher Carrying the Christ Child [detail]. 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 500 Spitz Hours, Paris, ca. 1420. Tempera, gold, Los Angeles, California 90049-1682 and ink on parchment bound between www.getty.edu pasteboard covered with red silk velvet, 247 leaves, 20.3 x 14.8 cm (715/ie x 5% in.). Christopher Hudson, Publisher Los Angeles, J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. 57, Mark Greenberg, Editor in Chief 94.ML.26, fol. 42V (see Figure 7). Mollie Holtman and Tobi Kaplan, Editors Frontispiece: Diane Mark-Walker, Copy Editor Spitz Master, The Virgin and Child Jeffrey Cohen, Series Designer Enthroned [detail]. Spitz Hours, fol. 33V Suzanne Watson, Production Coordinator (see Figure 6). Christopher Foster, Photographer Typeset by G&S Typesetters, Inc., The books of the Bible are cited according Austin, Texas to their designations in the Douay-Rheims Printed in Hong Kong by Imago version translated from the Latin Vulgate. Library of Congress Full-page illustrations from the Spitz Hours Cataloging-in-Publication Data are reproduced at actual size. Clark, Gregory T., 1951- All photographs are copyrighted by the The Spitz master : a Parisian book of issuing institutions, unless otherwise noted. hours / Gregory T. Clark. p. cm. — (Getty Museum studies on art) Includes bibliographic references. ISBN 0-89236-712-1 i. Spitz hours—Illustrations. -

THE CATHOLIC UNIVERSITY of AMERICA the Voice of Mary: Later

THE CATHOLIC UNIVERSITY OF AMERICA The Voice of Mary: Later Medieval Representations of Marian Communication A DISSERTATION Submitted to the Faculty of the Department of History School of Arts and Sciences Of The Catholic University of America In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree Doctor of Philosophy © Copyright All Rights Reserved By Vanessa Rose Corcoran Washington, D.C. 2017 The Voice of Mary: Later Medieval Representations of Marian Communication Vanessa R. Corcoran Director: Katherine L. Jansen, Ph.D. It is nearly impossible to overstate the importance of the Virgin Mary’s role in the landscape of medieval Christian spirituality. Innumerable prayers, hymns, sermons, liturgical traditions, and other devotional practices praised her as the Mother of God and imagined her speaking profusely to her supplicants. Yet Mary only spoke in the Bible on four occasions (Luke 1:26-38, 1:46-56, 2:41-52, and John 2:1-11). Why then, given this limited speaking presence, were late medieval authors so intent on giving her an enhanced speaking role in textual sources that augmented her power? The striking transformation from the muted early Christian portrayals of Mary to the later medieval depictions of her as an outspoken matriarch cannot be ignored. My dissertation explores the emergence of Mary’s powerful persona through an examination of her speech as reported in narrative sources from the twelfth to the fifteenth century, including miracle collections, passion narratives, and mystery plays. Within both Latin and vernacular sources, authors expanded upon stories rooted in biblical and apocryphal literature to give Mary a new voice.