UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Altar Images

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Theme Park As "De Sprookjessprokkelaar," the Gatherer and Teller of Stories

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2018 Exploring a Three-Dimensional Narrative Medium: The Theme Park as "De Sprookjessprokkelaar," The Gatherer and Teller of Stories Carissa Baker University of Central Florida, [email protected] Part of the Rhetoric Commons, and the Tourism and Travel Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Doctoral Dissertation (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Baker, Carissa, "Exploring a Three-Dimensional Narrative Medium: The Theme Park as "De Sprookjessprokkelaar," The Gatherer and Teller of Stories" (2018). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 5795. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/5795 EXPLORING A THREE-DIMENSIONAL NARRATIVE MEDIUM: THE THEME PARK AS “DE SPROOKJESSPROKKELAAR,” THE GATHERER AND TELLER OF STORIES by CARISSA ANN BAKER B.A. Chapman University, 2006 M.A. University of Central Florida, 2008 A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the College of Arts and Humanities at the University of Central Florida Orlando, FL Spring Term 2018 Major Professor: Rudy McDaniel © 2018 Carissa Ann Baker ii ABSTRACT This dissertation examines the pervasiveness of storytelling in theme parks and establishes the theme park as a distinct narrative medium. It traces the characteristics of theme park storytelling, how it has changed over time, and what makes the medium unique. -

Copyright by Cary Cordova 2005

Copyright by Cary Cordova 2005 The Dissertation Committee for Cary Cordova Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: THE HEART OF THE MISSION: LATINO ART AND IDENTITY IN SAN FRANCISCO Committee: Steven D. Hoelscher, Co-Supervisor Shelley Fisher Fishkin, Co-Supervisor Janet Davis David Montejano Deborah Paredez Shirley Thompson THE HEART OF THE MISSION: LATINO ART AND IDENTITY IN SAN FRANCISCO by Cary Cordova, B.A., M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin December, 2005 Dedication To my parents, Jennifer Feeley and Solomon Cordova, and to our beloved San Francisco family of “beatnik” and “avant-garde” friends, Nancy Eichler, Ed and Anna Everett, Ellen Kernigan, and José Ramón Lerma. Acknowledgements For as long as I can remember, my most meaningful encounters with history emerged from first-hand accounts – autobiographies, diaries, articles, oral histories, scratchy recordings, and scraps of paper. This dissertation is a product of my encounters with many people, who made history a constant presence in my life. I am grateful to an expansive community of people who have assisted me with this project. This dissertation would not have been possible without the many people who sat down with me for countless hours to record their oral histories: Cesar Ascarrunz, Francisco Camplis, Luis Cervantes, Susan Cervantes, Maruja Cid, Carlos Cordova, Daniel del Solar, Martha Estrella, Juan Fuentes, Rupert Garcia, Yolanda Garfias Woo, Amelia “Mia” Galaviz de Gonzalez, Juan Gonzales, José Ramón Lerma, Andres Lopez, Yolanda Lopez, Carlos Loarca, Alejandro Murguía, Michael Nolan, Patricia Rodriguez, Peter Rodriguez, Nina Serrano, and René Yañez. -

{PDF} Pain in the Sass

PAIN IN THE SASS - ALL YOU NEED IS LOVE! (AND WI- FI) PDF, EPUB, EBOOK none | 32 pages | 13 Sep 2018 | Ravette Publishing Ltd | 9781841614069 | English | Horsham, United Kingdom Pain in the Sass - All You Need is Love! (and Wi-Fi) PDF Book The key to that is conscious relating. If you find you need more than three SSIDs, perhaps look into other ways of segregating the wireless access. Sticker Forever. Giebler and living in London when they decided to visit family in New Jersey for Christmas in Perfect for phone cases, laptops , journals, guitars, refrigerators, windows, walls, skateboards, cars , bumpers, helmets , water bottles, hydro flasks , computers, or whatever needs a dose of originality. Read on for a lovely dose of LOVE, and feel free to leave a comment with your own favorite quote about love! Tags: xxx tentacion, makeouthill, make out hill, bad vibes, badvibes, rip, love, rapper, music, musician, great, ski the slump god, bad vibes forever, bad, vibes, forever. For more details see Performance Tests: Wired Ethernet and Sell your art. Read our Privacy Policy and Terms and Conditions. Staying away from your own hard drive allows you to use software without leaving any trace of it at all on your system, as well as protecting your personal information. Allow this article to act as a great reminder to simply live in love! Select it and enter your network password to finish connecting. Devices must have wireless adapters to connect wirelessly to Wi-Fi, and most current laptops and mobile devices have these adapters built in. Tags: the originals, original, vampire, werewolf, hybrid, tribrid, always and forever, always and forever, mikaelson, tvd, klaus, niklaus, rebekah, elijah, kol, kai, parker, hope, finn, freya, esther, mikael, davina, camille, damon salvatore, stefan, salvatore, caroline, klaroline, klebekah, klelijah. -

Celebrations Press PO BOX 584 Uwchland, PA 19480

Enjoy the magic of Walt Disney World all year long with Celebrations magazine! Receive 1 year for only $29.99* *U.S. residents only. To order outside the United States, please visit www.celebrationspress.com. Subscribe online at www.celebrationspress.com, or send a check or money order to: Celebrations Press PO BOX 584 Uwchland, PA 19480 Be sure to include your name, mailing address, and email address! If you have any questions about subscribing, you can contact us at [email protected] or visit us online! Cover Photography © Garry Rollins Issue 67 Fall 2019 Welcome to Galaxy’s Edge: 64 A Travellers Guide to Batuu Contents Disney News ............................................................................ 8 Calendar of Events ...........................................................17 The Spooky Side MOUSE VIEWS .........................................................19 74 Guide to the Magic of Walt Disney World by Tim Foster...........................................................................20 Hidden Mickeys by Steve Barrett .....................................................................24 Shutters and Lenses by Mike Billick .........................................................................26 Travel Tips Grrrr! 82 by Michael Renfrow ............................................................36 Hangin’ With the Disney Legends by Jamie Hecker ....................................................................38 Bears of Disney Disney Cuisine by Erik Johnson ....................................................................40 -

Día De Los Muertos K-12 Educator’S Guide

Día de los Muertos K-12 Educator’s Guide Produced by the University of New Mexico Latin American & Iberian Institute Latin American & Iberian Institute Because of the geographic location and unique cultural history of New Mexico, the University of New Mexico (UNM) has emphasized Latin American Studies since the early 1930s. In 1979, the Latin American & Iberian Institute (LAII) was founded to coordinate Latin American programs on campus. Designated a National Resource Center (NRC) by the U.S. Department of Education, the LAII offers academic degrees, supports research, provides development opportunities for faculty, and coordinates an outreach program that reaches diverse constituents. In addition to the Latin American Studies (LAS) degrees offered, the LAII supports Latin American studies in departments and professional schools across campus by awarding stu- dent fellowships and providing funds for faculty and curriculum development. The LAII’s mission is to create a stimulating environment for the production and dissemination of knowl- edge of Latin America and Iberia at UNM. We believe our goals are best pursued by efforts to build upon the insights of more than one academic discipline. In this respect, we offer interdisciplinary resources as part of our effort to work closely with the K-12 community to help integrate Latin American content mate- rials into New Mexico classrooms across grade levels and subject areas. We’re always glad to work with teachers to develop resources specific to their classrooms and students. To discuss this option, or for more comprehensive information about the LAII and its K-12 resources, contact: University of New Mexico Latin American & Iberian Institute 801 Yale Boulevard NE MSC02 1690 1 University of New Mexico Albuquerque, NM 87131 Phone: (505) 277-2961 Fax: (505) 277-5989 Email: [email protected] Web: http://laii.unm.edu *Images: Cover photograph of calavera provided courtesy of Reid Rosenberg, reprinted here under CC ©. -

Intro Alebrije.Pdf

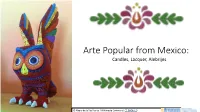

Arte Popular from Mexico: Candles, Lacquer, Alebrijes © Alvaro de la Paz Franco / Wikimedia Commons/ CC BY-SA 4.0 What is arte popular? Arte Popular is a Spanish term that translates to Popular Art in English. Another word for Arte Popular is artesanias. These can be arts like paintings and pottery, but they also include food, dance, and clothes. These arts are unique to Mexico and the communities that live in it. After the Mexican Revolution of the 1910s, focus was turned to Native Amerindian and farming communities. These communities were creating works of art but they had been ignored. But, after the revolution, Mexico needed something that could unite the people of Mexico. They decided to use the traditional arts of its people. Arte popular/artesanias became the heart of Mexico. You can go to Mexico now and visit artists’ workshops and © Thelmadatter / Edgar Adalberto Franco Martinez Ayotoxco De Guerrero, Puebla at see how they create their beautiful art. the Encuentro de las Colecciones de Arte Popular Valoración y Retos at the Franz Mayer Museum in Mexico City / Wikimedia Commons/ CC BY-SA 4.0 Arte popular/artesanias are traditions of many years within their communities. It is this community aspect that has provided Mexico with an art that focuses on the everyday people. It is why the word ‘popular’ is used to label these kinds of arts. The amazing objects they create, whether it is ceramic bowls or painted chests, are all unique and specific to the communities This is why there is so much variety in Mexico, because it is a large country. -

![Cuaderno 90 2021 Cuadernos Del Centro De Estudios En Diseño Y Comunicación [Ensayos]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8283/cuaderno-90-2021-cuadernos-del-centro-de-estudios-en-dise%C3%B1o-y-comunicaci%C3%B3n-ensayos-238283.webp)

Cuaderno 90 2021 Cuadernos Del Centro De Estudios En Diseño Y Comunicación [Ensayos]

ISSN 1668-0227 Año 21 Número 90 Enero Cuaderno 90 2021 Cuadernos del Centro de Estudios en Diseño y Comunicación [Ensayos] Investigar en Diseño: del complejo y multívoco diálogo entre el Diseño y las artesanías Marina Laura Matarrese y Luz del Carmen Vilchis Esquivel: Prólogo || Eje 1 Reflexiones conceptuales acerca del cruce entre diseño y artesanía | Luz del Carmen Vilchis Esquivel: Del símbo- lo a la trama | María Laura Garrido: La división arte/artesanía y su relación con la construcción de una historia del diseño | Marco Antonio Sandoval Valle: Relaciones de complejidad e identidad entre artesanía y diseño | Miguel Angel Rubio Toledo: El Diseño sistémico transdisciplinar para el desarrollo sostenible neguentró- pico de la producción artesanal | Yésica A. del Moral Zamudio: La innovación en la creación y comercialización de animales fan- tásticos en Arrazola, Oaxaca | Mónica Susana De La Barrera Me- dina: El diseño como objeto artesanal de consumo e identidad || Eje 2. La relación diseño y artesanía en los pueblos indígenas | Paola Trocha: Las artesanías Zenú: transformaciones y continui- dades como parte de diversas estrategias artesanales | Mercedes Martínez González y Fernando García García: El espejo en que nos vemos juntos: la antropología y el diseño en la creación de un video mapping arquitectónico con una comunidad purépecha de México | Paolo Arévalo Ortiz: La cultura visual en el proceso del tejido Puruhá | Daniela Larrea Solórzano: La artesanía salasaca y sus procesos de transculturación estética | Annabella Ponce Pérez y Carolina Cornejo Ramón: El diseño textil como resultado de la interacción étnica en Quito, a finales del siglo XVIII | Verónica Ariza y Mar Itzel Andrade: La relación artesanía y diseño. -

Movements of Diverse Inquiries As Critical Teaching Practices Among Charros, Tlacuaches and Mapaches Stephen T

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Open Access Dissertations 9-2012 Movements of Diverse Inquiries as Critical Teaching Practices Among Charros, Tlacuaches and Mapaches Stephen T. Sadlier University of Massachusetts Amherst, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/open_access_dissertations Part of the Education Commons Recommended Citation Sadlier, Stephen T., "Movements of Diverse Inquiries as Critical Teaching Practices Among Charros, Tlacuaches and Mapaches" (2012). Open Access Dissertations. 664. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/open_access_dissertations/664 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Open Access Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MOVEMENTS OF DIVERSE INQUIRIES AS CRITICAL TEACHING PRACTICES AMONG CHARROS, TLACUACHES AND MAPACHES A Dissertation Presented by STEPHEN T. SADLIER Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF EDUCATION September 2012 School of Education Language, Literacy, and Culture © Copyright by Stephen T. Sadlier 2012 All Rights Reserved MOVEMENTS OF DIVERSE INQUIRIES AS CRITICAL TEACHING PRACTICES AMONG CHARROS,1 TLACUACHES2 AND MAPACHES3 A Dissertation Presented By STEPHEN T. SADLIER Approved as to style and content -

Newsletter May 2021

NEWSLETTER MAY 2021 ABEL TASMAN VILLAGE RECREATION PROGRAM MAY 2021 I will be commencing my maternity leave on the 21st May 2021 and expect to return in January 2022. In my absence, the lovely Margaret Russell will step into the role of General Manager. I am sure many of you have had the pleasure of meeting Margaret who has been part of the ATV Management Team since April 2020. Margaret has over 20 years of experience in aged care and is very well qualified to step into the role in my absence. Please feel free to come and introduce yourself and say ‘hi’ to Margaret next time you are at ATV. Thank you for all the love and support from families, staff and volunteers. I will be seeing you all very soon. Mitchell (Left) is our newly Richa (Left) is our newly appointed Maintenance appointment Office Supervisor. He is very Manager. She has over 6 experienced and has over 8 years experience in Aged years experience in aged Care as Consumer Relations care. Mitch joined the ATV Consultant and 3 years family in April 2020 and experience as an AIN already feels like he is party (Assistant in Nursing). of our family. Welcome Richa. Our COVID-19 Vaccination programme is near to completing for our residents. The first dose was administered on 13th April 2021 with great success, the second will be completed by 4th May 2021. The consent form is still valid from the previous vaccination round, and once again we request that on the Vaccination day, we would appreciate if you can limit your visits, as we require all resources to assist with the Vaccination. -

Arte Queer Chicano

bitácora arquitectura + número 34 EN Arte queer chicano Uriel Vides Bautista A mediados de 2015, la Galería de la Raza exhibió un mural que provocó triarcales de la sociedad dominante y los valores hegemónicos de la mascu- una acalorada discusión en redes sociales y actos de iconoclastia contem- linidad chicana, reafirmando a la vez el hecho de ser bilingües y biculturales poránea. El mural, que representa a sujetos queer, fue violentado tres veces dentro de Estados Unidos. consecutivas debido a cierta homofobia cultural que prevalece dentro de un sector de la comunidad chicana asentada en Mission District, San Fran- cisco. El contenido de esta obra y la significación dentro de su contexto son II algunos aspectos que analizaré a lo largo de este breve ensayo. El mural digital de Maricón Collective se inserta dentro de la tradición mu- ralista chicana, que tiene su origen en los murales que “los tres grandes”8 pintaron en distintos lugares de Estados Unidos, pero principalmente en I California. Mientras que en México el muralismo agotaba sus temáticas y La Galería de la Raza se encuentra ubicada en la 24th Street de Mission agonizaba junto con la vida de Siqueiros, en Estados Unidos resurgía de for- District, el barrio más antiguo de San Francisco.1 Este barrio fue en la década ma asombrosa gracias al Movimiento Chicano. Durante este periodo, según de 1970, en palabras del historiador Manuel G. Gonzales, “el corazón del George Vargas, los barrios chicanos de las principales ciudades del país se movimiento muralista de la ciudad”. La proliferación de murales fue impul- cubrieron de coloridos murales que, realizados de manera comunitaria, ex- sada, en este periodo, por los aires renovadores del llamado Movimiento presaban temas fundamentales para la comunidad como la raza, la clase, el Chicano.2 Ante la falta de espacios adecuados para la recreación y el espar- orgullo étnico y la denuncia social.9 cimiento, artistas y activistas chicanos pugnaron por la creación de centros En un ensayo, Edward J. -

Day of the Dead Traditions in Rural Mexican Villages

IN RURAL MEXICAN VILLAGES by Ann Murdy , writer and photographer ay of the Dead, or Día de los Muertos as it is known in México, is a celebration of life. It is a time we honor and celebrate the lives of those who are no longer with us by constructing home altars, or ofrendas, in their memory and visiting their graves. An altar brings a Dloved one back to life, and relatives place on it all the things the person once enjoyed eating or drinking. Additionally, ofrendas include mementos, photos of the relative, and a glass of water and bread. The altars are adorned with marigold flowers which represent the fragility of life. A pathway of vibrant marigold petals is sprinkled from the outside of the home to the foot of the altar. This pathway, adorned with lit candles, guides the souls back to the home. Sweet- smelling copal, an incense-like resin, is burned to aid in communication with the spirits. The Spanish friars brought All Saints’ Day (November 1) and All Souls’ Day (November 2) to México in the sixteenth century. In order to convert the indigenous people to Christianity, the friars allowed the people of México to continue their death rituals in November of each year. The earliest festival was the Aztec Festival of the Little Dead, which took place in Tlaxochimaco, the ninth month of their calendar, July 24–August 12. This festival honored children who had died. The second festival, the Great Festival of the Dead, took place during Huey Miccailhuitontli, the tenth month, August 13–September 1. -

Rituals of the Past in the Context of the Present

Rituals of the past in the context of the present The role of Remembrance Day and Liberation Day in Dutch society Manja Coopmans 15217-Coopmans_BNW.indd 1 06-02-18 09:36 Manuscript committee: Prof. dr. M. J. A. M. Verkuyten (Utrecht University) Prof. dr. A. B. Dijkstra (University of Amsterdam) Prof. dr. C. R. Ribbens (Erasmus University Rotterdam / NIOD) Rituals of the past in the context of the present Prof. dr. P. L. H. Scheepers (Radboud University Nijmegen) The role of Remembrance Day and Liberation Day in Dutch society Prof. dr. H. A. G. de Valk (University of Groningen / NIDI) Rituelen uit het verleden in de context van het heden De rol van Dodenherdenking en Bevrijdingsdag in de Nederlandse samenleving (met een samenvatting in het Nederlands) Cover illustrations Erik Voncken Proefschrift Cover design Betekende Wereld Printing Ridderprint BV ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Universiteit Utrecht op gezag van de rector magnificus, ISBN 978-90-393-6937-1 prof. dr. G. J. van der Zwaan, ingevolge het besluit van het college voor promoties in het openbaar te verdedigen op 16 maart 2018 des middags te 12.45 uur © 2018 Manja Coopmans door All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any Manja Coopmans information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the author. The copyright of the articles that have been accepted for publication or that already have been geboren op 22 juni 1989 published, has been transferred to the respective journals.