Course Outline

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Barbie Bake-Off and Risk Or Role the Apprentice Model? Documentary Pokémon Go Shorts

FEBRUARY 2017 ISSUE 59 POST-TRUTH RESEARCHING THE PAST BARBIE BAKE-OFF AND RISK OR ROLE THE APPRENTICE MODEL? DOCUMENTARY POKÉMON GO SHORTS MM59_cover_4_feb.indd 1 06/02/2017 14:00 Contents 04 Making the Most of MediaMag MediaMagazine is published by the English and Media 06 What’s the Truth in a Centre, a non-profit making Post-fact World? organisation. The Centre Nick Lacey explores the role publishes a wide range of of misinformation in recent classroom materials and electoral campaigns, and runs courses for teachers. asks who is responsible for If you’re studying English 06 gate-keeping online news. at A Level, look out for emagazine, also published 10 NW and the Image by the Centre. System at Work in the World Andrew McCallum explores the complexities of image and identify in the BBC television 30 16 adaptation of Zadie Smith’s acclaimed novel, NW. 16 Operation Julie: Researching the Past Screenwriter Mike Hobbs describes the challenges of researching a script for a sensational crime story forty years after the event. 20 20 Bun Fight: How The BBC The English and Media Centre 18 Compton Terrace Lost Bake Off to Channel 4 London N1 2UN and Why it Matters Telephone: 020 7359 8080 Jonathan Nunns examines Fax: 020 7354 0133 why the acquisition of Bake Email for subscription enquiries: Off may be less than a bun [email protected] in the oven for Channel 4. 25 Mirror, Mirror, on the Editor: Jenny Grahame Wall… Mark Ramey introduces Copy-editing: some of the big questions we Andrew McCallum should be asking about the Subscriptions manager: nature of documentary film Bev St Hill 10 and its relationship to reality. -

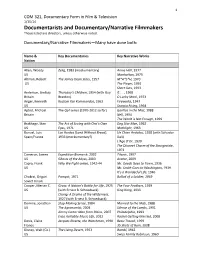

Documentarists and Documentary/Narrative Filmmakers Those Listed Are Directors, Unless Otherwise Noted

1 COM 321, Documentary Form in Film & Television 1/15/14 Documentarists and Documentary/Narrative Filmmakers Those listed are directors, unless otherwise noted. Documentary/Narrative Filmmakers—Many have done both: Name & Key Documentaries Key Narrative Works Nation Allen, Woody Zelig, 1983 (mockumentary) Annie Hall, 1977 US Manhattan, 1979 Altman, Robert The James Dean Story, 1957 M*A*S*H, 1970 US The Player, 1992 Short Cuts, 1993 Anderson, Lindsay Thursday’s Children, 1954 (with Guy if. , 1968 Britain Brenton) O Lucky Man!, 1973 Anger, Kenneth Kustom Kar Kommandos, 1963 Fireworks, 1947 US Scorpio Rising, 1964 Apted, Michael The Up! series (1970‐2012 so far) Gorillas in the Mist, 1988 Britain Nell, 1994 The World is Not Enough, 1999 Brakhage, Stan The Act of Seeing with One’s Own Dog Star Man, 1962 US Eyes, 1971 Mothlight, 1963 Bunuel, Luis Las Hurdes (Land Without Bread), Un Chien Andalou, 1928 (with Salvador Spain/France 1933 (mockumentary?) Dali) L’Age D’Or, 1930 The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie, 1972 Cameron, James Expedition Bismarck, 2002 Titanic, 1997 US Ghosts of the Abyss, 2003 Avatar, 2009 Capra, Frank Why We Fight series, 1942‐44 Mr. Deeds Goes to Town, 1936 US Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, 1939 It’s a Wonderful Life, 1946 Chukrai, Grigori Pamyat, 1971 Ballad of a Soldier, 1959 Soviet Union Cooper, Merian C. Grass: A Nation’s Battle for Life, 1925 The Four Feathers, 1929 US (with Ernest B. Schoedsack) King Kong, 1933 Chang: A Drama of the Wilderness, 1927 (with Ernest B. Schoedsack) Demme, Jonathan Stop Making Sense, -

A Communication Study of Contemporary Documentary Film

University of Mississippi eGrove Honors College (Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors Theses Honors College) 2007 Art and Persuasion: A Communication Study of Contemporary Documentary Film Lauren Elizabeth Freeman Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/hon_thesis Recommended Citation Freeman, Lauren Elizabeth, "Art and Persuasion: A Communication Study of Contemporary Documentary Film" (2007). Honors Theses. 2004. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/hon_thesis/2004 This Undergraduate Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors College (Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College) at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ART AND PERSUASION: A COMMUNICATION STUDY OF CONTEMPORARY DOCUMENTARY FILM By Lauren Elizabeth Freeman A thesis submitted to the faculty of the University of Mississippi in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College. Oxford May 2007 Approved by , , L Ad^or: Professor Joe Atkins Readei1p^fessoLPmch£ll££maiiuel,PhD Reader: Professor Charles Gates, PhD ©2007 Lauren Elizabeth Freeman ALL RIGHTS RESRERVED ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The author of this paper incurs many debts of gratitude throughout the long and tedious process of completing this honors senior thesis. A special expression of gratitude goes to my thesis adviser, Professor Joseph Atkins, for his supportive direction throughout the preparation of this research project. Sincere appreciation is extended to niy thesis readers. Dr. Michelle Emanuel and Dr. Charles Gates, and to those filmmakers who shared their time and thoughts with me on documentary filmmaking. I extend my heartfelt gratitude to my family and fnends for their continued support and encouragement. -

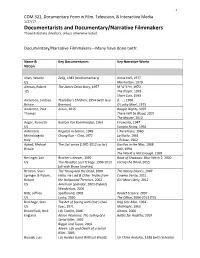

Documentarists and Documentary/Narrative Filmmakers Those Listed Are Directors, Unless Otherwise Noted

1 COM 321, Documentary Form in Film, Television, & Interactive Media 1/27/17 Documentarists and Documentary/Narrative Filmmakers Those listed are directors, unless otherwise noted. Documentary/Narrative Filmmakers—Many have done both: Name & Key Documentaries Key Narrative Works Nation Allen, Woody Zelig, 1983 (mockumentary) Annie Hall, 1977 US Manhattan, 1979 Altman, Robert The James Dean Story, 1957 M*A*S*H, 1970 US The Player, 1992 Short Cuts, 1993 Anderson, Lindsay Thursday’s Children, 1954 (with Guy if. , 1968 Britain Brenton) O Lucky Man!, 1973 Anderson, Paul Junun, 2015 Boogie Nights, 1997 Thomas There Will be Blood, 2007 The Master, 2012 Anger, Kenneth Kustom Kar Kommandos, 1963 Fireworks, 1947 US Scorpio Rising, 1964 Antonioni, Ragazze in bianco, 1949 L’Avventura, 1960 Michelangelo Chung Kuo – Cina, 1972 La Notte, 1961 Italy L'Eclisse, 1962 Apted, Michael The Up! series (1970‐2012 so far) Gorillas in the Mist, 1988 Britain Nell, 1994 The World is Not Enough, 1999 Berlinger, Joe Brother’s Keeper, 1992 Book of Shadows: Blair Witch 2, 2000 US The Paradise Lost Trilogy, 1996-2011 Facing the Wind, 2015 (all with Bruce Sinofsky) Berman, Shari The Young and the Dead, 2000 The Nanny Diaries, 2007 Springer & Pulcini, Hello, He Lied & Other Truths from Cinema Verite, 2011 Robert the Hollywood Trenches, 2002 Girl Most Likely, 2012 US American Splendor, 2003 (hybrid) Wanderlust, 2006 Blitz, Jeffrey Spellbound, 2002 Rocket Science, 2007 US Lucky, 2010 The Office, 2006-2013 (TV) Brakhage, Stan The Act of Seeing with One’s Own Dog Star Man, -

Cold War: a Report on the Xviith IAMHIST Conference, 25-31 July 1997, Salisbury MD

After the Fall: Revisioning the Cold War: A Report on the XVIIth IAMHIST Conference, 25-31 July 1997, Salisbury MD By John C. Tibbetts “The past can be seized only as an image,” wrote Walter Benjamin. But if that image is ignored by the present, it “threatens to disappear irretrievably.” [1] One such image, evocative of the past and provocative for our present, appears in a documentary film by the United States Information Agency, The Wall (1963). Midway through its account of everyday life in a divided Berlin, a man is seen standing on an elevation above the Wall, sending out hand signals to children on the other side in the Eastern Sector. With voice communication forbidden by the Soviets, he has only the choreography of his hands and fingers with which to print messages onto the air. Now, almost forty years later, the scene resonates with an almost unbearable poignancy. From the depths of the Cold War, the man seems to be gesturing to us. But his message is unclear and its context obscure. [2] The intervening gulf of years has become a barrier just as impassable as the Wall once was. Or has it? The Wall was just one of dozens of screenings and presentations at the recent “Knaves, Fools, and Heroes: Film and Television Representations of the Cold War”—convened as a joint endeavor of IAMHist and the Literature/Film Association, 25-31 July 1997, at Salisbury State University, in Salisbury, Maryland— that suggested that the Cold War is as relevant to our present as it is to our past. -

1,000 Films to See Before You Die Published in the Guardian, June 2007

1,000 Films to See Before You Die Published in The Guardian, June 2007 http://film.guardian.co.uk/1000films/0,,2108487,00.html Ace in the Hole (Billy Wilder, 1951) Prescient satire on news manipulation, with Kirk Douglas as a washed-up hack making the most of a story that falls into his lap. One of Wilder's nastiest, most cynical efforts, who can say he wasn't actually soft-pedalling? He certainly thought it was the best film he'd ever made. Ace Ventura: Pet Detective (Tom Shadyac, 1994) A goofy detective turns town upside-down in search of a missing dolphin - any old plot would have done for oven-ready megastar Jim Carrey. A ski-jump hairdo, a zillion impersonations, making his bum "talk" - Ace Ventura showcases Jim Carrey's near-rapturous gifts for physical comedy long before he became encumbered by notions of serious acting. An Actor's Revenge (Kon Ichikawa, 1963) Prolific Japanese director Ichikawa scored a bulls-eye with this beautifully stylized potboiler that took its cues from traditional Kabuki theatre. It's all ballasted by a terrific double performance from Kazuo Hasegawa both as the female-impersonator who has sworn vengeance for the death of his parents, and the raucous thief who helps him. The Addiction (Abel Ferrara, 1995) Ferrara's comic-horror vision of modern urban vampires is an underrated masterpiece, full- throatedly bizarre and offensive. The vampire takes blood from the innocent mortal and creates another vampire, condemned to an eternity of addiction and despair. Ferrara's mob movie The Funeral, released at the same time, had a similar vision of violence and humiliation. -

57 the War Game: Sahte Belgesel Gerçek Endişe

The War Game: Sahte Belgesel Gerçek Endişe Seçkin SEVİM1 “Teknik ve zihinsel açıdan atom çağında yaşıyoruz. Duygusal açıdan ise hâlâ Taş Devri’nde yaşıyoruz.” The War Game Özet Peter Watkins‟in (1935-…) The War Game (1965) filmi, kendini belgesel olarak sunan bir kurmacadır. Postmodern bir anlatı formu olan sahte belgesel türünün en ilginç örneklerinden biridir. BBC‟nin sınırlı prodüksiyon imkânlarıyla gerçekleştirdiği bu televizyon filmi, kurmaca bir içeriğe sahip olmasına rağmen 1966 yılında En İyi Belgesel Film Oscar‟ını almıştır. Filmde Soğuk Savaş döneminin (1945-1991) en büyük tehdidi olan nükleer saldırının yaratabileceği trajik sonuçlara dikkat çekilmektedir. BBC, The War Game filmini toplumda yaratabileceği infial nedeniyle ancak yirmi yıl sonra Soğuk Savaş gerginliğinin azaldığı bir dönemde gösterebilmiştir. Bu çalışmanın amacı, The War Game‟de sahte belgesel estetiğinin nasıl oluşturulduğunu Norman Fairclough‟un Eleştirel Söylem Çözümlemesi (ESÇ) yöntemiyle incelemektir. Çalışmanın bulguları; nükleer saldırı öncesi, nükleer saldırı anı ve nükleer saldırı sonrası olmak üzere üç ana kategoride yorumlanmaktadır. Bir nükleer saldırının özellikle sivil halkı etkileyecek trajik sonuçlar doğuracağı ve Nazi Almanya‟sına benzer iktidar ilişkilerine yol açacağı eleştirel bir dille simüle edilmektedir. Anahtar Kelimeler: Sahte Belgesel, Soğuk Savaş, Nükleer Saldırı, Eleştirel Söylem Çözümlemesi. The War Game: Mock Documentary Real Concern Abstract Peter Watkins‟ (1935-…) The War Game (1965) is a fiction film presenting itself as a documentary. It is one of the most interesting examples of the mock documentary genre which is a postmodern narrative form. This television film, produced by the BBC with limited production means, received an Oscar for Best Documentary Film in 1966 despite its fictional content. It draws attention to the possible tragic consequences of the nuclear attack as the 1 Dr. -

Desired Ground Zeroes: Nuclear Imagination and the Death Drive Calum Lister Matheson a Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty At

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Carolina Digital Repository Desired Ground Zeroes: Nuclear Imagination and the Death Drive Calum Lister Matheson A dissertation submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Communication Studies. Chapel Hill 2015 Approved by: Carole Blair Ken Hillis Chris Lundberg Todd Ochoa Sarah Sharma © 2015 Calum Lister Matheson ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Calum Lister Matheson: Desired Ground Zeroes: Nuclear Imagination and the Death Drive (Under the direction of Chris Lundberg and Sarah Sharma) A wide variety of cultural artefacts related to nuclear warfare are examined to highlight continuity in the sublime’s mix of horror and fascination. Schemes to use nuclear explosions for peaceful purposes embody the godlike structural positions of the Bomb for Americans in the early Cold War. Efforts to mediate the Real of the Bomb include nuclear simulations used in wargames and their civilian offshoots in videogames and other media. Control over absence is examined through the spatial distribution of populations that would be sacrificed in a nuclear war and appeals to overarching rationality to justify urban inequality. Control over presence manifests in survivalism, from Cold War shelter construction to contemporary “doomsday prepping” and survivalist novels. The longstanding cultural ambivalence towards nuclear war, coupled with the manifest desire to experience the Real, has implications for nuclear activist strategies that rely on democratically-engaged publics to resist nuclear violence once the “truth” is made clear. -

Appendix Screenings and Additional Resources

Appendix Screenings and Additional Resources The analyses of various films and television programmes undertaken in this book are intended to function ‘interactively’ with screenings of the films and programmes. To this end, a complete list of works to accompany each chapter is provided below. Certain of these works are available from national and international distribution companies. Specific locations in the United States, the United Kingdom and Australia for each of the listed works are, nevertheless, provided below. The entries include running time and format (16 mm, VHS, or DVD) for each work. (Please note: In certain countries films require copyright clearance for public screening.) Also included below are further or additional screenings of works not analysed or referred to in each chapter. This information is supplemented by suggested further reading. 1 ‘Believe me, I’m of the world’: documentary representation Further reading Corner, J. ‘Civic visions: forms of documentary’ in J. Corner, Television Form and Public Address (London: Edward Arnold, 1995). Corner, J. ‘Television, documentary and the category of the aesthetic’, Screen, 44, 1 (2003) 92–100. Nichols, B. Blurred Boundaries: Questions of Meaning in Contemporary Culture (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1994). Renov, M. ‘Toward a poetics of documentary’ in M. Renov (ed.), Theorizing Documentary (New York: Routledge, 1993). 2 Men with movie cameras: Flaherty and Grierson Nanook of the North, Robert Flaherty, 1922. 55 min. (Alternative title: Nanook of the North: A Story -

Iraq War Documentaries in the Online Public Sphere

Embedded Online: Iraq War Documentaries in the Online Public Sphere Eileen Culloty, MA This thesis is submitted to Dublin City University for the award of PhD in the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences. Dublin City University School of Communications Supervisor: Dr. Pat Brereton September 2014 I hereby certify that this material, which I now submit for assessment on the programme of study leading to the award of Doctor of Philosophy is entirely my own work, that I have exercised reasonable care to ensure that the work is original, and does not to the best of my knowledge breach any law of copyright, and has not been taken from the work of others save and to the extent that such work has been cited and acknowledged within the text of my work. Signed: ___________ ID No.: ___________ Date: _________ ii DEDICATION This work is dedicated to the memory of Martin Culloty. … I go back beyond the old man Mind and body broken To find the unbroken man. It is the moment before the dance begins. Your lips are enjoying themselves Whistling an air. Whatever happens or cannot happen In the time I have to spare I see you dancing father Brendan Kennelly (1990) ‘I See You Dancing Father’ iii TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT ............................................................................................................................ vii LIST OF FIGURES ................................................................................................................ viii ABBREVIATIONS ................................................................................................................... -

Jack C. Ellis and Betsy A. Mclane

p A NEW HISTORY OF DOCUMENTARY FILM Jack c. Ellis and Betsy A. McLane .~ continuum NEW YOR K. L ONDON - Contents Preface ix Chapter 1 Some Ways to Think About Documentary 1 Description 1 Definition 3 Intellectual Contexts 4 Pre-documentary Origins 6 Books on Documentary Theory and General Histories of Documentary 9 Chapter 2 Beginnings: The Americans and Popular Anthropology, 1922-1929 12 The Work of Robert Flaherty 12 The Flaherty Way 22 Offshoots from Flaherty 24 Films of the Period 26 Books 011 the Period 26 Chapter 3 Beginnings: The Soviets and Political btdoctrinatioll, 1922-1929 27 Nonfiction 28 Fict ion 38 Films of the Period 42 Books on the Period 42 Chapter 4 Beginnings: The European Avant-Gardists and Artistic Experimentation, 1922-1929 44 Aesthetic Predispositions 44 Avant-Garde and Documentary 45 Three City Symphonies 48 End of the Avant-Garde 53 Films of the Period 55 Books on the Period 56 v = vi CONTENTS Chapter 5 Institutionalization: Great Britain, 1929- 1939 57 Background and Underpinnings 57 The System 60 The Films 63 Grierson and Flaherty 70 Grierson's Contribution 73 Films of the Period 74 Books on the Period 75 Chapter 6 Institutionalization: United States, /930- 1941 77 Film on the Left 77 The March of Time 78 Government Documentaries 80 Nongovernment Documentaries 92 American and British Differences 97 Denouement 101 An Aside to Conclude 102 Films of the Period 103 Books on the Period 103 Chapter 7 Expansion: Great Britain, 1939- 1945 105 Early Days 106 Indoctrination 109 Social Documentary 113 Records of Battle -

Documentary Film 3. Filmmakers' Theories Introduction

Component 2 Global filmmaking perspectives Section B: Documentary Film 3. Filmmakers’ Theories Introduction (from the specification) The documentary film will be explored in relation to key filmmakers from the genre. The documentary film studied may either directly embody aspects of these theories or work in a way that strongly challenges these theories. In either case, the theories will provide a means of exploring different approaches to documentary film and filmmaking. Two of the following filmmakers' theories must be chosen for study: Peter Watkins Watkins established his reputation with two docu-dramas from the 1960s, Culloden and The War Game. Both document events from the past using actors and reconstruction. In asking questions of conventional documentary, Watkins reflects his deep concern with mainstream media, which he has called the ‘monoform’. Nick Broomfield Broomfield, like Michael Moore, has developed a participatory, performative mode of documentary filmmaking. Broomfield is an investigative documentarist with a distinctive interview technique which he uses to expose people's real views. Like Watson, he keeps the filmmaking presence to a minimum, normally with a crew of no more than three. He describes his films as 'like a rollercoaster ride. They’re like a diary into the future.' 1 Kim Longinotto Longinotto has said 'I don’t think of films as documents or records of things. I try to make them as like the experience of watching a fiction film as possible, though, of course, nothing is ever set up.' Her work is about finding characters that the audience will identify with – 'you can make this jump into someone else’s experience'.