Numismatique

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Processes of Byzantinisation and Serbian Archaeology Byzantine Heritage and Serbian Art I Byzantine Heritage and Serbian Art I–Iii

I BYZANTINE HERITAGE AND SERBIAN ART I BYZANTINE HERITAGE AND SERBIAN ART AND SERBIAN BYZANTINE HERITAGE PROCESSES OF BYZANTINISATION AND SERBIAN ARCHAEOLOGY BYZANTINE HERITAGE AND SERBIAN ART I BYZANTINE HERITAGE AND SERBIAN ART I–III Editors-in-Chief LJUBOMIR MAKSIMOVIć JELENA TRIVAN Edited by DANICA POPOVić DraGAN VOJVODić Editorial Board VESNA BIKIć LIDIJA MERENIK DANICA POPOVić ZoraN raKIć MIODraG MARKOVić VlADIMIR SIMić IGOR BOROZAN DraGAN VOJVODić Editorial Secretaries MARka TOMić ĐURić MILOš ŽIVKOVIć Reviewed by VALENTINO PACE ElIZABETA DIMITROVA MARKO POPOVić MIROSLAV TIMOTIJEVIć VUJADIN IVANIšEVić The Serbian National Committee of Byzantine Studies P.E. Službeni glasnik Institute for Byzantine Studies, Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts PROCESSES OF BYZANTINISATION AND SERBIAN ARCHAEOLOGY Editor VESNA BIKIć BELGRADE, 2016 PUBLished ON THE OCCasiON OF THE 23RD InternatiOnaL COngress OF Byzantine STUdies This book has been published with the support of the Ministry of Education, Science and Technological Development of the Republic of Serbia CONTENTS PREFACE 11 I. BYZANTINISATION IN THE ARCHAEOLOGICAL CONTEXT THE DYNAMICS OF BYZANTINE–SERBIAN POLITICAL RELATIONS 17 Srđan Pirivatrić THE ‘MEDIEVAL SERBIAN OECUMENE’ – FICTION OR REALITY? 37 Mihailo St. Popović BYZANTINE INFLUENCE ON ADMINISTRATION IN THE TIME OF THE NEMANJIĆ DYNASTY 45 Stanoje Bojanin Bojana Krsmanović FROM THE ROMAN CASTEL TO THE SERBIAN MEDIEVAL CITY 53 Marko Popović THE BYZANTINE MODEL OF A SERBIAN MONASTERY: CONSTRUCTION AND ORGANISATIONAL CONCEPT 67 Gordana -

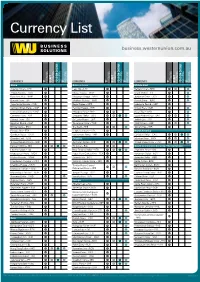

View Currency List

Currency List business.westernunion.com.au CURRENCY TT OUTGOING DRAFT OUTGOING FOREIGN CHEQUE INCOMING TT INCOMING CURRENCY TT OUTGOING DRAFT OUTGOING FOREIGN CHEQUE INCOMING TT INCOMING CURRENCY TT OUTGOING DRAFT OUTGOING FOREIGN CHEQUE INCOMING TT INCOMING Africa Asia continued Middle East Algerian Dinar – DZD Laos Kip – LAK Bahrain Dinar – BHD Angola Kwanza – AOA Macau Pataca – MOP Israeli Shekel – ILS Botswana Pula – BWP Malaysian Ringgit – MYR Jordanian Dinar – JOD Burundi Franc – BIF Maldives Rufiyaa – MVR Kuwaiti Dinar – KWD Cape Verde Escudo – CVE Nepal Rupee – NPR Lebanese Pound – LBP Central African States – XOF Pakistan Rupee – PKR Omani Rial – OMR Central African States – XAF Philippine Peso – PHP Qatari Rial – QAR Comoros Franc – KMF Singapore Dollar – SGD Saudi Arabian Riyal – SAR Djibouti Franc – DJF Sri Lanka Rupee – LKR Turkish Lira – TRY Egyptian Pound – EGP Taiwanese Dollar – TWD UAE Dirham – AED Eritrea Nakfa – ERN Thai Baht – THB Yemeni Rial – YER Ethiopia Birr – ETB Uzbekistan Sum – UZS North America Gambian Dalasi – GMD Vietnamese Dong – VND Canadian Dollar – CAD Ghanian Cedi – GHS Oceania Mexican Peso – MXN Guinea Republic Franc – GNF Australian Dollar – AUD United States Dollar – USD Kenyan Shilling – KES Fiji Dollar – FJD South and Central America, The Caribbean Lesotho Malati – LSL New Zealand Dollar – NZD Argentine Peso – ARS Madagascar Ariary – MGA Papua New Guinea Kina – PGK Bahamian Dollar – BSD Malawi Kwacha – MWK Samoan Tala – WST Barbados Dollar – BBD Mauritanian Ouguiya – MRO Solomon Islands Dollar – -

The Mineral Industries of the Southern Balkans in 2004

THE MINERAL INDUSTRIES OF THE SOUTHERN BALKANS ALBANIA, BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA, CROATIA, MACEDONIA, SERBIA AND MONTENEGRO, AND SLOVENIA By Walter G. Steblez Europe’s Adriatic Balkan region is part of the southern Mineral deposits that usually have been associated with portion of the Mediterranean Alpine folded zone, which extends Albania included such metalliferous mineral commodities through the Dinarides of the former Yugoslavia (Bosnia and as chromite, copper ore, and nickeliferous iron ore and such Herzegovina, Croatia, Macedonia, Serbia and Montenegro, mineral fuels as natural gas and petroleum. Of the metal ores, and Slovenia), the Albanides of Albania, and the Hellenides of only chromite and a token amount of bauxite were mined in Greece. Mining for base and precious metals may be traced 2004. In past decades, Albania was among the world’s top through historical records to at least 5th century B.C. Evidence three producers and exporters of chromite. Although Albania’s of early workings at the Bor copper deposit in Serbia suggests chromite output remained insubstantial compared with routine prehistoric origins. production levels reached during the 960s through the late Mineral deposits in the region became well defined during 980s, the output of marketable chromite (concentrate and the second half of the 20th century. Commercial resources direct shipping ore) increased significantly by about 67% in of major base metals included those of aluminum, chromium, 2004 compared with that of 2003. The output of ferrochromium cobalt, copper, iron, lead, magnesium, manganese, nickel, and declined by about 8% compared with that of 2003 (table ). zinc. Such precious metals as gold, palladium, platinum, and Many of the country’s remaining mineral producing silver were found mainly in association with such base metals enterprises were under foreign operational management. -

Exchange Rate Statistics

Exchange rate statistics Updated issue Statistical Series Deutsche Bundesbank Exchange rate statistics 2 This Statistical Series is released once a month and pub- Deutsche Bundesbank lished on the basis of Section 18 of the Bundesbank Act Wilhelm-Epstein-Straße 14 (Gesetz über die Deutsche Bundesbank). 60431 Frankfurt am Main Germany To be informed when new issues of this Statistical Series are published, subscribe to the newsletter at: Postfach 10 06 02 www.bundesbank.de/statistik-newsletter_en 60006 Frankfurt am Main Germany Compared with the regular issue, which you may subscribe to as a newsletter, this issue contains data, which have Tel.: +49 (0)69 9566 3512 been updated in the meantime. Email: www.bundesbank.de/contact Up-to-date information and time series are also available Information pursuant to Section 5 of the German Tele- online at: media Act (Telemediengesetz) can be found at: www.bundesbank.de/content/821976 www.bundesbank.de/imprint www.bundesbank.de/timeseries Reproduction permitted only if source is stated. Further statistics compiled by the Deutsche Bundesbank can also be accessed at the Bundesbank web pages. ISSN 2699–9188 A publication schedule for selected statistics can be viewed Please consult the relevant table for the date of the last on the following page: update. www.bundesbank.de/statisticalcalender Deutsche Bundesbank Exchange rate statistics 3 Contents I. Euro area and exchange rate stability convergence criterion 1. Euro area countries and irrevoc able euro conversion rates in the third stage of Economic and Monetary Union .................................................................. 7 2. Central rates and intervention rates in Exchange Rate Mechanism II ............................... 7 II. -

Countries Codes and Currencies 2020.Xlsx

World Bank Country Code Country Name WHO Region Currency Name Currency Code Income Group (2018) AFG Afghanistan EMR Low Afghanistan Afghani AFN ALB Albania EUR Upper‐middle Albanian Lek ALL DZA Algeria AFR Upper‐middle Algerian Dinar DZD AND Andorra EUR High Euro EUR AGO Angola AFR Lower‐middle Angolan Kwanza AON ATG Antigua and Barbuda AMR High Eastern Caribbean Dollar XCD ARG Argentina AMR Upper‐middle Argentine Peso ARS ARM Armenia EUR Upper‐middle Dram AMD AUS Australia WPR High Australian Dollar AUD AUT Austria EUR High Euro EUR AZE Azerbaijan EUR Upper‐middle Manat AZN BHS Bahamas AMR High Bahamian Dollar BSD BHR Bahrain EMR High Baharaini Dinar BHD BGD Bangladesh SEAR Lower‐middle Taka BDT BRB Barbados AMR High Barbados Dollar BBD BLR Belarus EUR Upper‐middle Belarusian Ruble BYN BEL Belgium EUR High Euro EUR BLZ Belize AMR Upper‐middle Belize Dollar BZD BEN Benin AFR Low CFA Franc XOF BTN Bhutan SEAR Lower‐middle Ngultrum BTN BOL Bolivia Plurinational States of AMR Lower‐middle Boliviano BOB BIH Bosnia and Herzegovina EUR Upper‐middle Convertible Mark BAM BWA Botswana AFR Upper‐middle Botswana Pula BWP BRA Brazil AMR Upper‐middle Brazilian Real BRL BRN Brunei Darussalam WPR High Brunei Dollar BND BGR Bulgaria EUR Upper‐middle Bulgarian Lev BGL BFA Burkina Faso AFR Low CFA Franc XOF BDI Burundi AFR Low Burundi Franc BIF CPV Cabo Verde Republic of AFR Lower‐middle Cape Verde Escudo CVE KHM Cambodia WPR Lower‐middle Riel KHR CMR Cameroon AFR Lower‐middle CFA Franc XAF CAN Canada AMR High Canadian Dollar CAD CAF Central African Republic -

2015 / DEFI 15-08 Detection of Implicit Fluctuation Bands and Their

DOCUMENTOS DE ECONOMÍA Y FINANZAS INTERNACIONALES Working Papers on International Economics and Finance DEFI 15-08 May 2015 Detection of Implicit Fluctuation Bands and their Credibility in Candidate Countries Simón Sosvilla-Rivero María del Carmen Ramos Herrera Asociación Española de Economía y Finanzas Internacionales www.aeefi.com ISSN: 1696-6376 Detection of Implicit Fluctuation Bands and their Credibility in Candidate Countries SIMÓN SOSVILLA-RIVERO Universidad Complutense de Madrid, Facultad de Ciencias Económicas y Empresariales Campus de Somosaguas, 28223, Madrid, Spain. MARÍA DEL CARMEN RAMOS-HERRERA Universidad Complutense de Madrid, Facultad de Ciencias Económicas y Empresariales Campus de Somosaguas, 28223, Madrid, Spain. e-mail: [email protected] Abstract: This paper attempts to identify implicit exchange rate regimes for currencies of candidate countries vis-à-vis the euro. To that end, we apply three sequential procedures that consider the dynamics of exchange rates to data covering the period from 1999:01 to 2012:12. Our results would suggest that implicit bands have existed in many sub-periods for almost all currencies under study. Once we detect de facto discrepancies between de facto and de iure exchange rate regimes, we make use of different methods to study the credibility of the detected fluctuation bands. The detected lack of credibility in a high percentage of the sample is robust using the Drift Adjustment method and discrete choice models, suggesting that economic agents do not behave as if these bands actually were in force at time of making their financial plans. These countries do not improve the confidence on the fluctuation bands as time evolves. -

Mineco Three Mines Full Operation and Production in 2019

Mineco three mines full operation and production in 2019 Mineco Group System, Business Results Summary for 2019 Mineco Group has fulfilled its Plans The British company Mineco Group, one of the largest mining investors in Serbia and the Western Balkans, is pleased with the results achieved in 2019, as it fulfilled its investment plans and the mines in the Group had certain sales of products. “In terms of Mineco results in this region during 2019, this was a year of great and many small challenges. First of all, it was successful because we managed to provide certain sales of the products from our mines and to maintain the level of planned investments, although the situation on the market for the metals we deal with, became even more complex due to disruptions in the US-China trade relations”, said Mineco Group Director Bojan Popovic in Belgrade. Popović reminded that Mineco achieved the best results in 2017 since its establishment, while in the second half of 2018, prices on the international market of non-ferrous metals decreased, which directly affected the mines resulting in lower revenues. “This trend continued into 2019, but it did not slow Mineco’s development programme,” he added. The mines operating within Mineco Group at full capacity – Rudnik Mine and Flotation near Gornji Milanovac, Veliki Majdan near Ljubovija and Gross Mine near Srebrenica, have continued a number of successful years – having fulfilled their production plans, continued exploration works and confirmed mine reserves. Popović pointed out that Rudnik Mine on the Mountain of Rudnik achieved a special success because it managed to discover and confirm new mineral resources. -

WM/Refinitiv Closing Spot Rates

The WM/Refinitiv Closing Spot Rates The WM/Refinitiv Closing Exchange Rates are available on Eikon via monitor pages or RICs. To access the index page, type WMRSPOT01 and <Return> For access to the RICs, please use the following generic codes :- USDxxxFIXz=WM Use M for mid rate or omit for bid / ask rates Use USD, EUR, GBP or CHF xxx can be any of the following currencies :- Albania Lek ALL Austrian Schilling ATS Belarus Ruble BYN Belgian Franc BEF Bosnia Herzegovina Mark BAM Bulgarian Lev BGN Croatian Kuna HRK Cyprus Pound CYP Czech Koruna CZK Danish Krone DKK Estonian Kroon EEK Ecu XEU Euro EUR Finnish Markka FIM French Franc FRF Deutsche Mark DEM Greek Drachma GRD Hungarian Forint HUF Iceland Krona ISK Irish Punt IEP Italian Lira ITL Latvian Lat LVL Lithuanian Litas LTL Luxembourg Franc LUF Macedonia Denar MKD Maltese Lira MTL Moldova Leu MDL Dutch Guilder NLG Norwegian Krone NOK Polish Zloty PLN Portugese Escudo PTE Romanian Leu RON Russian Rouble RUB Slovakian Koruna SKK Slovenian Tolar SIT Spanish Peseta ESP Sterling GBP Swedish Krona SEK Swiss Franc CHF New Turkish Lira TRY Ukraine Hryvnia UAH Serbian Dinar RSD Special Drawing Rights XDR Algerian Dinar DZD Angola Kwanza AOA Bahrain Dinar BHD Botswana Pula BWP Burundi Franc BIF Central African Franc XAF Comoros Franc KMF Congo Democratic Rep. Franc CDF Cote D’Ivorie Franc XOF Egyptian Pound EGP Ethiopia Birr ETB Gambian Dalasi GMD Ghana Cedi GHS Guinea Franc GNF Israeli Shekel ILS Jordanian Dinar JOD Kenyan Schilling KES Kuwaiti Dinar KWD Lebanese Pound LBP Lesotho Loti LSL Malagasy -

Serbia Euro-Asia Unitary Country

SERBIA EURO-ASIA UNITARY COUNTRY Basic socio-economic indicators Income group - UPPER MIDDLE INCOME Local currency - SERBIAN DINAR (RSD) Population and geography Economic data AREA: 77 474 km2 GDP: 96.9 billion (current PPP international dollars) i.e. 13 592 dollars per inhabitant (2014) POPULATION: million inhabitants (2014), 7.129 REAL GDP GROWTH: -1.8% (2014 vs 2013) a decrease of 0.6 % per year (2010-2014) UNEMPLOYMENT RATE: 18.9% (2014) 2 DENSITY: 92 inhabitants/km FOREIGN DIRECT INVESTMENT, NET INFLOWS (FDI): 2 000 (BoP, current USD millions, 2014) URBAN POPULATION: 55.6% of national population GROSS FIXED CAPITAL FORMATION (GFCF): 15.6% of GDP (2014) CAPITAL CITY: Belgrade (16.6% of national population) HUMAN DEVELOPMENT INDEX: 0.771 (high), rank 66 Sources: World Bank Development Indicators, UNDP-HDI, ILO Territorial organisation and subnational government RESPONSIBILITIES MUNICIPAL LEVEL INTERMEDIATE LEVEL REGIONAL OR STATE LEVEL TOTAL NUMBER OF SNGs 174 - 2 176 23 Cities (grad) and 2 Autonomous Provinces 150 Municipalities (opstina) (Pokrajine Vojvodina + City of Belgrade aND Kosovo and Metohija) Average municipal size: 40 805 inhabitantS Main features of territorial organisation. Serbia is a unitary country with a one tier structure of government. This tier is composed by 150 municipalities (opstina), 23 Cities (grad) and the City of Belgrade, which are themselves divided into several subordinate administrative units (mesna zajednica). Municipalities (usually>10000hab), has an assembly, public service property and a budget. They comprise local communities. Cities (>100000) have an assembly and budget of its own. Municipalities and cities are gathered into larger entities known as districts which are regional centers of state authority. -

The Image of States, Nations and Religions in Medieval and Early Modern East Central Europe

The Image of States, Nations and Religions in Medieval and Early Modern East Central Europe THE IMAGE OF STATES, NATIONS AND RELIGIONS IN MEDIEVAL AND EARLY MODERN EAST CENTRAL EUROPE Edited by Attila Bárány and Réka Bozzay, in co-operation with Balázs Antal Bacsa Debrecen 2018 MEMORIA HUNGARIAE 2 SeriesMEMORIA Editor: HUNGARIAEAttila Bárány 5 Series Editor: Attila Bárány Published by the Hungarian Academy of Sciences - University of Debrecen “Lendület” PublishedHungary by the Hungarian in Medieval Academy Europe ofResearch Sciences Group - University (LP-2014-13/2014) of Debrecen “Lendület” Hungary in Medieval Europe Research Group (LP-2014-13/2014) Editor-in-Chief: Attila Bárány Editor-in-Chief: Attila Bárány Sponsord by the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, Office for Research Groups Sponsored by the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, Office for Research Groups Copy-editor: Copy-editor: Balázs Balázs Antal Antal Bacsa Bacsa Desktop editing, layout and cover design by Desktop editing, layout and cover design by Anett Lapis-Lovas – Járom Kulturális Egyesület Anett Lapis-Lovas – Járom Kulturális Egyesület ISBN 978-963-508-881-2 ISBNISSN 978-963-508-833-1 2498-7794 ISSN 2498-7794 © “Lendület” Hungary in Medieval Europe Research Group, 2018 © “Lendület” Hungary ©in TheMedieval Authors, Europe 2018 Research Group, 2016 © The Authors, 2016 All rights reserved. No part of thisAll publication rights reserved. may be reproduced, stored in a retrievalNo part system,of this publication or transmitted may in be any reproduced, form or by any means, storedelectronic, in a retrieval mechanical, system, or photocopying, transmitted in recording, any form oror otherwise,by any means, electronic,without mechanical, the prior writtenphotocopying, permission recording, of the orPublisher. -

Inflation in Serbia and in the European Union*

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by EBOOKS Repository ORIGINAL SCIENFITIC PAPER Inflation in Serbia and in the European Union* Vukotić-Cotič Gordana, Institute of Economic Sciences, Belgrade Stošić Ivan, Institute of Economic Sciences, Belgrade UDC: 339.745(497.11:4) JEL: E31, F31 ABSTRACT – Administration cannot be practiced in isolation of the culture of the society. This assertion implies that the knowledge, attitude, societal norms and orientation which people hold epitomize their administrative philosophy and the way it is practiced. KEY WORDS: Serbia, EU, EMU, inflation, real exchange rate of the Serbian dinar Introduction In this paper we shall compare the rate of inflation in Serbia with the rate of inflation in the European Union (EU), to find out how much Serbia – as a potential candidate country to the EU – diverges from general price tendencies exhibited by EU member states. We shall also examine the real exchange rate of the Serbian dinar to the euro, the single currency within the European Economic and Monetary Union (EMU), bearing in mind the role it plays in Serbia’s trade policy. Finally, we shall observe the structure of inflation by main items of household consumption in both Serbia and the EU – to contrast the standard of living in Serbia with the standard of living in the EU. The rates of inflation will be derived from the index of consumer prices in Serbia and the harmonized index of consumer prices in the EU1. The index of consumer prices in Serbia is methodologically compatible with the harmonized index of consumer prices in the EU. -

Papal Power, Local Communities And

PAPAL POWER, LOCAL COMMUNITIES AND PRETENDERS: THE CHURCH OF CROATIA, DALMATIA AND SLAVONIA AND THE STRUGGLE FOR THE THRONE OF THE KINGDOM OF HUNGARY-CROATIA (1290-1301) Mišo Petrović Abstract. Previous research has mainly concentrated on whether or not the Apostolic See actively supported, obstructed or ignored the rise of the Angevins to the throne of Hungary between 1290 and 1301. Whatever papal stance historians supported coloured how they explained changes that occurred in this period in the Church organization of Croatia, Dalmatia and Slavonia, and what role these adjustments played in the subsequent arrival of Charles Robert to the throne of Hungary in 1301. Instead, I have analyzed local developments and how these were interconnected with the international situation and how each influenced one another. This included assessing the motivations behind the actions of three major players who brought Charles Robert to Hungary: the Apostolic See, the Angevin court in Naples and the local oligarchs, the Šubići. Although other explanations for the cooperation between these three parties can be supported, namely the cultural, economic and political factors, the focus of this paper is on changes in the local Church structures. I tracked how each of the involved parties contributed to these developments and used local Church reforms for their personal gain. This paper evaluates the inextricably related agendas of the Apostolic See, the Angevins and the Šubići at the close of the thirteenth century. THE RIVAL AND THE VASSAL OF CHARLES ROBERT OF ANJOU: KING VLADISLAV II NEMANJIĆ Aleksandar Krstić Abstract. Vladislav II (c. 1270–after 1326) was the son of Serbian King Stefan Dragutin (1276–1282, d.