Short Remarks on the Political and Social Writings Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bluegrass Cavalcade

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Literature in English, North America English Language and Literature 1956 Bluegrass Cavalcade Thomas D. Clark Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Thanks to the University of Kentucky Libraries and the University Press of Kentucky, this book is freely available to current faculty, students, and staff at the University of Kentucky. Find other University of Kentucky Books at uknowledge.uky.edu/upk. For more information, please contact UKnowledge at [email protected]. Recommended Citation Clark, Thomas D., "Bluegrass Cavalcade" (1956). Literature in English, North America. 20. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/upk_english_language_and_literature_north_america/20 Bluegrass Cavalcade ~~ rvN'_r~ ~ .,J\{.1' ~-.---· ~ '( , ~\ -'"l-.. r: <-n' ~1"-,. G.. .... UNIVERSITY OF KENTUCKY PRESS Lexington 1956 - Edited by THOMAS D. CLARK .'-" ,_ r- Publication of this book is possible partly because of a grant from the Margaret Voorhies Haggin Trust established in memory of her husband James Ben Ali Haggin. Copyright © 1956 by The University of Kentucky Press Paperback edition © 2009 by the University Press of Kentucky The University Press of Kentucky Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth, serving Bellarmine University, Berea College, Centre College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University, The Filson Historical Society, Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University, Morehead State University, Murray State University, Northern Kentucky University, Transylvania University, University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, and Western Kentucky University. All rights reserved. Editorial and Sales Offices: The University Press of Kentucky 663 South Limestone Street, Lexington, Kentucky 40508-4008 www.kentuckypress.com Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available from the Library of Congress. -

Annual Report to the Congress: January 1 to September 30, 1983

Annual Report to the Congress: January 1 to September 30, 1983 March 1984 Contents Section Page I. Statements by the Chairman and Vice Chairman of the Board, TAAC Chairman, and the Director of OTA. 1 II. Year in Review . 5 III, Work in Progress . 21 IV. Organization and Operations . 23 Appendixes A. List of Advisors and Panel Members . 33 B. OTA Act–Public Law 92-484 . 68 Section I.-Statements by the Chairman and Vice Chairman of the Board, TAAC Chairman, and the Director of OTA CHAIRMAN’S STATEMENT- CONGRESSMAN MORRIS K. UDALL The year 1983 was very productive for the Office of Technology Assessment. OTA made substantive contributions to about 60 different committees and subcommittees. They ranged from major, comprehen- sive reports to testimony and special analyses, Considering the com- plex and controversial nature of the issues OTA must deal with, it is commendable that its work continues to be given uniformly high marks for quality, fairness, and usefulness. During 1983, OTA was active in such diverse areas as hazardous and nuclear waste management, acid rain analyses, cost containment of health care, technology and trade policy, Love Canal, wood use, and polygraphs. The evidence of testimony, briefings, other requests for assistance, as well as reception of OTA’s products by committees em- phasizes the contribution made by OTA to the legislative process. 2 ● Annual Report to the Congress for 1983 VICE CHAIRMAN’S STATEMENT- SENATOR TED STEVENS The lives of our citizens and the issues of government have increas- ingly been influenced by science and technology. Congressional com- mittees and Members are drawn into the complexity of science and the controversies involving technology as they face the necessary deci- sions of government. -

1998-1997 Annual Report

VIRGINIA S TATE B AR 60th A NNUAL R EPORT for the period July 1, 1997 - June 30, 1998 V IRGINIA S TATE B AR 707 East Main Street, Suite 1500 Q Richmond, Virginia 23219-2803 804.775.0500 Fax 804.775.0501 Voice/TTD 804.775.0502 www.vsb.org T ABLE OF C ONTENTS A DMINISTRATIVE / GOVERNING Report of the President . .4 Report of the Executive Director/Chief Operating Officer . .6 Virginia State Bar Organizational Chart . .9 Report of the Treasurer . .10 Report of the Department of Professional Regulation . .11 Minutes of the 60th Annual Meeting . .22 In Memoriam . .23 R EPORTS OF THE S ECTIONS Administrative Law . .24 Antitrust, Franchise & Trade Regulation . .25 Bankruptcy . .26 Business Law . .27 Construction Law & Public Contracts . .28 Corporate Counsel . .29 Criminal Law . .30 Education of Lawyers in Virginia . .31 Environmental Law . .31 Family Law . .32 General Practice . .33 Health Law . .34 Intellectual Property . .35 International Practice . .36 Litigation . .37 Local Government Law . .38 Military Law . .39 Real Property . .40 Senior Lawyers . .41 Taxation . .42 Trusts & Estates . .43 Young Lawyers Conference . .44 REPORTS OF S TANDING C OMMITTEES Budget and Finance . .47 Lawyer Advertising and Solicitation . .47 Lawyer Discipline . .48 Legal Ethics . .49 Professionalism . .50 V IRGINIA S TATE B AR Q 1997~98 ANNUAL R EPORT T ABLE OF C ONTENTS REPORTS OF S PECIAL C OMMITTEES Access to Legal Services . .51 Alternative Dispute Resolution . .52 Bench-Bar Relations . .52 Code of Professional Responsibility . .53 Computer Needs of the Virginia State Bar . .54 Consistency in Disciplinary System . .55 Judicial Nominations . .56 Law Office Management Assistance Program . -

The Ancestors and Descendants of Colonel David Funsten and His Wife Susan Everard Meade

ALLEN COUNTY PUBLIC LIBRARY 3 1833 01239 20 Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2018 https://archive.org/details/ancestorsdescendOOdura fr THE ANCESTORS AND DESCENDANTS V OF COLONEL DAVID FUNSTEN _ __ , ir , - ■ --r — - - - - -Tirri'-r — ■ ————— AND HIS WIFE SUSAN EVERARD MEADE Compiled for HORTENSE FUNSTEN DURAND by Howard S. F. Randolph Assistant Librarian New York Genealogical and Biographical Society • • • • • • • • * • • • • » • i e • • • • • % • • • i j > • • • • • • Zht ^nitktTbtxtktt ^Ttss NEW YORK % 1926 M. wvj r» A - 1 V\ s <0 vC V »*' 1560975 Copyright, 1926 by Hortense Funsten Durand Made in the United States of America £ -a- . t To MY FATHER AND THE MEMORY OF MY MOTHER ' - ACKNOWLEDGMENT I wish to express my gratitude and hearty thanks to my friend Howard S. F. Randolph, compiler of this book, not only for the tremendous amount of work he has done, but also for the unfailing enthusiasm with which he greeted each new phase and overcame the many difficulties which arose. Mr. Randolph and I are also deeply indebted to Mrs. P. H. Baskervill of Richmond, Va., for her gracious permis¬ sion to quote freely (as we have done) from the book “Andrew Meade, of Ireland and Virginia,” written by her late husband. The data thus obtained have been of in¬ calculable assistance in compiling this history. I also acknowledge with sincere appreciation the cordial and interested co-operation of the following relatives: Mrs. Edwin Hinks, Elk Ridge, Maryland; Mr. Robert M. Ward, Winchester, Virginia; Miss Edith W. Smith, Denver, Colorado; Mrs. Montrose P. McArdle, Webster Grove, Missouri; Mr. William Meade Fletcher, Sperryville, Virginia; and last but not least to my father, Robert Emmett Fun- sten, for his interesting and valuable personal recollections. -

|||GET||| Apocalypticism in the Bible and Its World 1St Edition

APOCALYPTICISM IN THE BIBLE AND ITS WORLD 1ST EDITION DOWNLOAD FREE Frederick J Murphy | 9781441238740 | | | | | Persian and Hellenistic influences The American Jewish Experience. Eerdmans Publishing. Some adherents believe that the arrival or rediscovery of alien civilizations, technologies and spirituality will enable humans to overcome current ecological, spiritual and social problems. He also said that at this time knowledge of dharma will also be lost. Search for the book on E-ZBorrow. Messianism is the expectation for an end-time agent who plays a positive, authoritative, and usually redemptive role. Archived from the original on 8 December Use ILLiad for articles and chapter scans. Timothy P. Claims about the significance of those years, including the presence of Jesus Christ, the beginning of the " last days ", the destruction of worldly governments and the earthly resurrection of Jewish patriarchs, were successively abandoned. The righteous are rewarded with the pleasures of Jannah Paradisewhile the unrighteous are punished in Jahannam Hell. The Big Picture. Apocalypticism and messianism originated in ancient Judaism. Being of divine origin and divinely corroborated, present-truth chronology stands in a class by itself, absolutely and unqualifiedly correct. Modernity shaped apocalypticism profoundly. Jehovah's Witnesses state that this increase in knowledge needs adjustments. Americans have long evinced a fascination with the end of time and the role that they would play in such an apocalypse. Many scholars consider the worldview through the lens of a single religious perspective, usually New Testament Christianity. Increasingly pushed to the margins of American culture, evangelicals —many of whom became fundamentalists after the turn of the century—began to espouse a theology that looked toward the imminent return of Christ to claim His followers and prosecute His judgment against a sinful nation. -

Alumni @ Large

Colby Magazine Volume 92 Issue 4 Fall 2003 Article 10 October 2003 Alumni @ Large Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/colbymagazine Recommended Citation (2003) "Alumni @ Large," Colby Magazine: Vol. 92 : Iss. 4 , Article 10. Available at: https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/colbymagazine/vol92/iss4/10 This Contents is brought to you for free and open access by the Colby College Archives at Digital Commons @ Colby. It has been accepted for inclusion in Colby Magazine by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Colby. 1940s Alumni at Large 20s/30s racial restrictions in Virginia were in 1940s Correspondents effect at that time, the church remained Deaths: Helen E. Davis ’26, March 28, 2003, in Pittsfield, Maine, open to all races—and in the vanguard 1940 at 99 Edward M. Locke ’29, December 1, 1997, in Marquette, of civil and human relations, leading Ernest C. Marriner Jr. Mich., at 92 Harold F. Lemoine ’32, July 7, 2003, in San Diego, to the formation of the Fairfax County 10 Walnut Drive Calif., at 94 Ruth Leighton Thomas ’33, April 30, 2003, in Council on Human Relations. Rev- Augusta, ME 04330-6032 Pittsfield, Maine, at 91 Luke R. Pelletier ’37, January 31, 2003, erend Beckwith’s achievements listed 207-623-0543 in Port Orange, Fla., at 86 Albert W. Berrie ’38, July 21, 2003, in the award citation include “serv- [email protected] in Breezewood, Pa., at 87 William S. Hains ’38, June 6, 2001, ing as the first president of the Fairfax 1941 County Council on Human Relations, at 85 Roger E. -

Another Layer of Lies He Roman Republic Stood for Keeping Civic Dialogue Civil

The New Hampshire Gazette, Friday, September 29, 2017 — Page 1 A Non-Fiction Newspaper First Class U.S. The New Hampshire Gazette Postage Paid Grab Me! I’m Free! Portsmouth, N.H. The Nation’s Oldest Newspaper™ • Editor: Steven Fowle • Founded 1756 by Daniel Fowle Vol. CCLXII, No. 1 Permit No. 75 PO Box 756, Portsmouth, NH 03802 • [email protected] • www.nhgazette.com Address Service Requested September 29, 2017 The Fortnightly Rant Another Layer of Lies he Roman Republic stood for keeping civic dialogue civil. 500 years before lapsing into It was inevitable that our story- dictatorship.T The United States tellers of record would eventually of America, in half that time, has find themselves in an unenviable gone from George Washington’s position familiar to every Ameri- first inaugural address to Donald can President from FDR through Trump losing a battle of wits with George W. Bush: contemplating Kim Jong Un as Congress tries to Vietnam and asking, what the hell kill off constituents by depriving do I do about that? It’s not as if they them of healthcare. could ignore forever the most for- How the hell did that happen? mative event in U.S. history since Gradually and then suddenly, over WW II. Ten years ago they saw the the past seventy years—which hap- 50th anniversary coming and started pens to be the period covered by the doing the best they could. new documentary series, “The Viet- In interviews, the filmmakers nam War.” have been candid about the trepida- That half-forgotten war is our tion they felt over this volatile topic. -

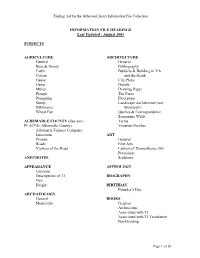

INFORMATION FILE HEADINGS Last Updated : August 2003

Finding Aid for the Jefferson Library Information File Collection INFORMATION FILE HEADINGS Last Updated : August 2003 SUBJECTS AGRICULTURE ARCHITECTURE General General Bees & Honey Bibliography Cattle Builders & Building in VA Cotton and the South Geese City Plans Hemp Details Mules Drawing Paper Plough The Farm Ploughing Floorplans Sheep Landscape Architecture (not Silkworms Monticello Wheat Fan Queries & Correspondence Serpentine Walls ALBEMARLE COUNTY (See also: Terms PLACES--Albemarle County) Venetian Porches Albemarle Furnace Company Limestone ART Prisons General Roads Fine Arts Viewers of the Road Lantern of Demosthenes (M) Portraiture ANECDOTES Sculpture APPEARANCE ASTROLOGY Cartoons Descriptions of TJ BIOGRAPHY Hair Height BIRTHDAY Founder’s Day ARCHAEOLOGY General BOOKS Monticello General Architecture Associated with TJ Associated with TJ Translation Bookbinding Page 1 of 20 Finding Aid for the Jefferson Library Information File Collection BOOKS (CONT’D) CONSTITUTION (See: POLITICAL Book Dealers LIFE--Constitution) Book Marks Book Shelves CUSTOMS Catalogs Goose Night Children’s Reading Classics DEATH Common Place Epitaphs Dictionaries Funeral Encyclopedias Last Words Ivory Books Law Books EDUCATION Library of Congress General Notes on the State of Virginia Foreign Languages Poplar Forest Reference Bibliographies ENLIGHTENMENT Restored Library Retirement Library FAMILY Reviews of Books Related to TJ Coat of Arms Sale of 1815 Seal Skipwith Letter TJ Copies Surviving FAMILY LIFE Children CALENDAR Christmas Marriage CANALS The "Monticello -

New Paltz Times Briefl Y Noted News of New Paltz, Highland, Gardiner Rosendale & Beyond

Special section New Paltz Rosendale Tribute Healthy Hudson Valley: Hudson Valley Ribfest returns Soy brings homestyle Protector of the Ridge: Healthy Communities to the fairgrounds August 17-19 Japanese cuisine to the area Remembering Bob Larsen INSIDE 8 6 7 THURSDAY, AUGUST 9, 2018 $1.50 VOL. 18, ISSUE 32 New Paltz Timesimes www.hudsonvalleyone.com NEWS OF NEW PALTZ, GARDINER, HIGHLAND, ROSENDALE & BEYOND Scenes from the Ulster County Fair Administrative arrival and departure for New Paltz School District by Sharyn Flanagan T THEIR RECENT regular meeting on Wednesday, Au- gust 1, the New Paltz Central ASchool District introduced the new assistant principal hired for New Paltz Middle School. Daniel Glenn was most recently with the Newburgh district, said Superintendent of Schools Maria Rice. Glenn was signed to a four- year probationary appointment eff ec- tive August 6 of this year through August 5, 2022. A meet-and-greet event for the community to meet the new assistant principal will be scheduled in the up- coming weeks. Now the search begins to fi nd a re- placement for retiring Duzine Elementa- WILL DENDIS ry School principal Debra Hogencamp, A girl catches some air on a jumping harness at the Ulster County Fair in New Paltz last week, with Skytop Tower in the whose resignation for retirement after distance. 26 years of employment was accepted by the board of trustees during Wednes- HE 130TH ULSTER County Fair rolled into town Tuesday, August 31, kicking off as usual with “carload day’s meeting. night,” where $50 buys access to unlimited rides for up to eight people. -

Beall-Booth Family Papers, 1778-1953

The Filson Historical Society Beall-Booth family Papers, 1778-1953 For information regarding literary and copyright interest for these papers, see the Curator of Collections. Size of Collection: 10.0 Cubic Feet Location Number: Mss./A/B365 Beall-Booth family Papers, 1778-1953 Scope and Content Note Collection includes the papers of Samuel Beall, his son Norborne Beall, and the Booth family of Meade County, Kentucky. Samuel Beall's papers detail his land speculation partnership with John May and others through correspondence, business and legal papers, and records of his and May's land speculation efforts in Kentucky. Beall's partnerships included David Meade, George Mason, Robert Morris, and James Mercer. Also included in his land papers is John May's entry book from 1780-1783 detailing land he attempted to acquire for various interests, including Beall, who he was involved with. Norborne Beall, who inherited most of his father's interests in Kentucky, spent his life dividing and selling his father's land. Through misguided investments and credit lines the younger Beall lost most of his inherited holdings. His papers include correspondence regarding buying, selling, and borrowing against his land; business records detailing the processes of parceling out the land and the credit fiasco that evolved out of his mismanagement of his finances; legal records relating to numerous suits filed against Beall; and his land papers detailing his vast holdings in Jefferson, Meade Breckinridge, and Shelby counties in Kentucky. His correspondence also includes several letters from Henry Clay, who was a personal friend, discussing politics, personal matters, and finances. -

2002–04 Catalog

UNIVERSITY OF RICHMOND UNDERGRADUATE CATALOG ACADEMIC SCHOOLS School of Arts and Sciences Robins School of Business Jepson School of Leadership Studies COORDINATE COLLEGES Richmond College Westhampton College F O R I N F O R M A T I O N : University of Richmond, Virginia 23173 (804) 289-8000 www.richmond.edu UNIVERSITY OF RICHMOND ACADEMIC CALENDARS C ONTENTS * 2002-03 A CADEMIC CALENDARS Academic Calendars ....... 3 FALL SEMESTER 2002 University Aug. 21, Wed. ............................. School of Arts and Sciences: New students arrive; of Richmond .................... 6 begin orientation Aug. 23, Fri. ................................. Registration/problem resolution for entering Admission ......................11 students Financial Affairs .............15 Aug. 24, Sat. ................................ Arts and Sciences, Business, Leadership Studies: All Student Life....................19 students arrive Aug. 26, Mon. ............................. Classes begin Academic Sept. 2, Mon. ............................... Labor Day (classes meet) Opportunities Sept. 6, Fri. .................................. Last day to file for May/August graduation and Support .................. 28 Oct. 11, Fri. ................................. Last day of classes prior to Fall break (Residence International Education .29 halls remain open) Academic Procedures ....33 Oct. 16, Wed. .............................. Classes resume Nov. 26, Tues. ............................. Thanksgiving break begins after classes General Education Curriculum .....................44 -

Chairman Osceola, Gov. Desantis Sign Gambling Agreement

Q&A with Tribal members Strong leadership Edward Aguilar graduate from FSU from Ahnie Jumper v COMMUNITY v 7A EDUCATION 2B SPORTS v 6B www.seminoletribune.org Free Volume XLV • Number 4 April 30, 2021 Chairman Osceola, Gov. DeSantis HHS: sign gambling agreement Demand for vaccine Tribe set to play major slows BY DAMON SCOTT role in sports Staff Reporter betting HOLLYWOOD — As the Seminole Tribe’s Covid-19 vaccination program enters BY BEVERLY BIDNEY its fifth month officials say there aren’t as Staff Reporter many people asking for the shots. Part of the reason is due to the success The Seminole Tribe and Gov. Ron of the vaccine strategy’s rollout and the DeSantis reached a long-awaited agreement hundreds who have already received the April 23 for a new gaming compact which shot. The tribe’s Health and Human Services would bring sports betting to the state. (HHS) department and Public Safety staff The governor and Chairman Marcellus have carried out the vaccine program through W. Osceola, Jr. signed the compact in a phased eligibility process. The outreach and Tallahassee. education to tribal members and the tribal In addition to offering craps and roulette community has been ongoing. at its casinos, the tribe will be able to conduct But Dr. Vandhana Kiswani-Barley, the sports betting and license it to horse tracks, executive director of HHS, said many have jai alai and dog tracks throughout the state. still not been vaccinated. The tribe will receive a percentage of every “The number of vaccines being requested sports bet placed.