Download (531Kb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Extending the Aerial: Uncovering Histories of Teletext and Telesoftware in Britain 2015-09-09

Repositorium für die Medienwissenschaft Alison Gazzard Extending the Aerial: Uncovering Histories of Teletext and Telesoftware in Britain 2015-09-09 https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/14121 Veröffentlichungsversion / published version Zeitschriftenartikel / journal article Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Gazzard, Alison: Extending the Aerial: Uncovering Histories of Teletext and Telesoftware in Britain. In: VIEW Journal of European Television History and Culture, Jg. 4 (2015-09-09), Nr. 7, S. 90– 98. DOI: https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/14121. Erstmalig hier erschienen / Initial publication here: https://doi.org/10.18146/2213-0969.2015.jethc083 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer Creative Commons - This document is made available under a creative commons - Namensnennung - Weitergabe unter gleichen Bedingungen 4.0 Attribution - Share Alike 4.0 License. For more information see: Lizenz zur Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu dieser Lizenz http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0 finden Sie hier: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0 volume 4 issue 7/2015 EXTENDING THE AERIAL UNCOVERING HISTORIES OF TELETEXT AND TELESOFTWARE IN BRITAIN Alison Gazzard Lecturer in Media Arts London Knowledge Lab UCL Institute of Education 23-29 Emerald Street London, WC1N 3QS [email protected] Abstract: Beyond their roles of broadcasting programmed content into the homes of people around the country, Britain’s British Broadcasting Corporation and Independent Television stations delivered additional content via home television sets. This article will explore the history of British teletext and telesoftware in the broader context of microprocessing developments during the late 1970s and early 1980s through a media archaeological framework of the terminology and traits. -

Communications

50 Communications How Long the Wait until We Can Call It Television Jerry BORRELL: Congressional Research sharing service that provides more than Service, Library of Congress, Washington, 100 different (nonbibliographic) data bases D.C* to about 5,000 users. The Warner and American Express joint project, QUBE This brief article will review videotex (also Columbus-based), utilizes cable and teletext. There is little need to define broadcast with a limited interactive capa terminology because new hybrid systems bility. It does not allow for on-demand are being devised almost constantly (hats provision of information; rather, it uses a off to OCLC's latest buzzword-Viewtel). polling technique. Antiope, the French Ylost useful of all would be an examination teletext system, used at KSL in St. Louis of the types of technology being used for last year and undergoing further tests in information provision. The basic require Los Angeles at KNXT in the coming year, ment for all systems is a data base-i.e., is only part of a complex data transmission data stored so as to allow its retrieval and system known as DIDon. Antiope is also display on a television screen. The interac at an experimental stage in France, with tions between the computer and the tele 2,500 terminals scheduled for use in 1981. vision screens are means to distinguish CEEFAX and Oracle, broadcast teletext technologies. In teletext and videotex a by the BBC and IBC in Britain, have an device known as a decoder uses data en estimated 100,000 users currently. Two coded onto the lines of a broadcast signal thousand adapted television sets are being (whatever the medium of transmission) to sold every month. -

An Introductory History of British Broadcasting

An Introductory History of British Broadcasting ‘. a timely and provocative combination of historical narrative and social analysis. Crisell’s book provides an important historical and analytical introduc- tion to a subject which has long needed an overview of this kind.’ Sian Nicholas, Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television ‘Absolutely excellent for an overview of British broadcasting history: detailed, systematic and written in an engaging style.’ Stephen Gordon, Sandwell College An Introductory History of British Broadcasting is a concise and accessible history of British radio and television. It begins with the birth of radio at the beginning of the twentieth century and discusses key moments in media history, from the first wireless broadcast in 1920 through to recent developments in digital broadcasting and the internet. Distinguishing broadcasting from other kinds of mass media, and evaluating the way in which audiences have experienced the medium, Andrew Crisell considers the nature and evolution of broadcasting, the growth of broadcasting institutions and the relation of broadcasting to a wider political and social context. This fully updated and expanded second edition includes: ■ The latest developments in digital broadcasting and the internet ■ Broadcasting in a multimedia era and its prospects for the future ■ The concept of public service broadcasting and its changing role in an era of interactivity, multiple channels and pay per view ■ An evaluation of recent political pressures on the BBC and ITV duopoly ■ A timeline of key broadcasting events and annotated advice on further reading Andrew Crisell is Professor of Broadcasting Studies at the University of Sunderland. He is the author of Understanding Radio, also published by Routledge. -

Contents Section 1 – Introduction Page 4

Contents Section 1 – Introduction Page 4 Section 2 – Key Terms and Definitions Page 5 Section 3 – The European Ecosystem Page 7 3.1 Challenges to Overcome Page 8 3.2 Programmatic Adoption in CTV Across Europe Page 14 Section 4 – A Deep-Dive Into the Programmatic CTV Supply Page 19 Chain and How to Understand It 4.1 Targeting and Buying Page 21 4.2 Deal Types Page 23 Section 5 – A Step-By-Step Guide to Planning and Page 25 Operating a CTV Campaign Programmatically Section 6 - Programmatic CTV Campaigns Re-Cap/Checklist Page 27 Section 7 - Campaign Measurement Page 28 7.1 Viewability Measurement Page 28 7.2 Actionable Brand Safety Page 29 7.3 Questions to Ask to Measure Campaigns Page 29 7.4 Transparency Solutions Page 30 7.4 The Future of CTV Measurement Page 31 Section 8 - Privacy and CTV Page 32 Section 9 – Key Considerations Page 34 2 Contents Section 10 – Best Practices Page 35 Section 11 – What the Future of Programmatic CTV Holds Page 36 Summary Page 41 Contributors Page 42 Glossary Page 44 3 Section 1. Introduction The European Connected TV (CTV) market has skyrocketed in recent years. Where the worlds of TV and digital have been gradually merging over time, more and more consumers have been tuning out of traditional linear TV options and moving into online streaming, paving the way for the CTV phenomenon. With significant increases in smart TVs, streaming apps and devices making TV content now so easily accessible, and the global pandemic meaning more time is being spent at home, the media landscape has not only shifted but has radically transformed to enable CTV to reach new heights. -

New Litigation Document

Case 20-32299-KLP Doc 295 Filed 06/09/20 Entered 06/09/20 20:05:53 Desc Main Document Page 1 of 145 Edward O. Sassower, P.C. (admitted pro hac vice) Michael A. Condyles (VA 27807) Steven N. Serajeddini, P.C. (admitted pro hac vice) Peter J. Barrett (VA 46179) Anthony R. Grossi (admitted pro hac vice) Jeremy S. Williams (VA 77469) KIRKLAND & ELLIS LLP Brian H. Richardson (VA 92477) KIRKLAND & ELLIS INTERNATIONAL LLP KUTAK ROCK LLP 601 Lexington Avenue 901 East Byrd Street, Suite 1000 New York, New York 10022 Richmond, Virginia 23219-4071 Telephone: (212) 446-4800 Telephone: (804) 644-1700 Facsimile: (212) 446-4900 Facsimile: (804) 783-6192 Proposed Co-Counsel to the Debtors and Debtors in Possession IN THE UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF VIRGINIA RICHMOND DIVISION ) In re: ) Chapter 11 ) INTELSAT S.A., et al., 1 ) Case No. 20-32299 (KLP) ) Debtors. ) (Jointly Administered) ) DEBTORS’ APPLICATION FOR ENTRY OF AN ORDER AUTHORIZING THE RETENTION AND EMPLOYMENT OF KIRKLAND & ELLIS LLP AND KIRKLAND & ELLIS INTERNATIONAL LLP AS ATTORNEYS FOR THE DEBTORS AND DEBTORS IN POSSESSION EFFECTIVE AS OF MAY 13, 2020 The above-captioned debtors and debtors in possession (collectively, the “Debtors”) file this application (the “Application”) for the entry of an order (the “Order”), substantially in the form attached hereto as Exhibit A, authorizing the Debtors to retain and employ Kirkland & Ellis LLP and Kirkland & Ellis International LLP (collectively, “Kirkland”) as their attorneys effective as of the Petition Date (as defined herein). In support of this Application, the Debtors submit the declaration of Steven N. -

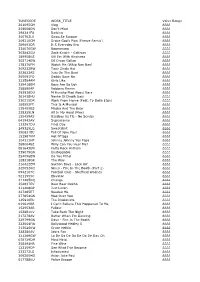

TUNECODE WORK TITLE Value Range 261095CM

TUNECODE WORK_TITLE Value Range 261095CM Vlog ££££ 259008DN Don't Mind ££££ 298241FU Barking ££££ 300703LV Swag Se Swagat ££££ 309210CM Drake God's Plan (Freeze Remix) ££££ 289693DR It S Everyday Bro ££££ 234070GW Boomerang ££££ 302842GU Zack Knight - Galtiyan ££££ 189958KS Kill Em With Kindness ££££ 302714EW Dil Diyan Gallan ££££ 178176FM Watch Me (Whip Nae Nae) ££££ 309232BW Tiger Zinda Hai ££££ 253823AS Juju On The Beat ££££ 265091FQ Daddy Says No ££££ 232584AM Girls Like ££££ 329418BM Boys Are So Ugh ££££ 258890AP Robbery Remix ££££ 292938DU M Huncho Mad About Bars ££££ 261438HU Nashe Si Chadh Gayi ££££ 230215DR Work From Home (Feat. Ty Dolla $Ign) ££££ 188552FT This Is A Musical ££££ 135455BS Masha And The Bear ££££ 238329LN All In My Head (Flex) ££££ 155459AS Bassboy Vs Tlc - No Scrubs ££££ 041942AV Supernanny ££££ 133267DU Final Day ££££ 249325LQ Sweatshirt ££££ 290631EU Fall Of Jake Paul ££££ 153987KM Hot N*Gga ££££ 304111HP Johnny Johnny Yes Papa ££££ 2680048Z Willy Can You Hear Me? ££££ 081643EN Party Rock Anthem ££££ 239079GN Unstoppable ££££ 254096EW Do You Mind ££££ 128318GR The Way ££££ 216422EM Section Boyz - Lock Arf ££££ 325052KQ Nines - Fire In The Booth (Part 2) ££££ 0942107C Football Club - Sheffield Wednes ££££ 5211555C Elevator ££££ 311205DQ Change ££££ 254637EV Baar Baar Dekho ££££ 311408GP Just Listen ££££ 227485ET Needed Me ££££ 277854GN Mad Over You ££££ 125910EU The Illusionists ££££ 019619BR I Can't Believe This Happened To Me ££££ 152953AR Fallout ££££ 153881KV Take Back The Night ££££ 217278AV Better When -

User Manual Contents

Register your product and get support at www.philips.com/welcome User Manual Contents 8.1 Satellite channels 35 1 My new TV 4 8.2 Watching satellite channels 35 1.1 Smart TV 4 8.3 Satellite channel list 35 1.2 App gallery 4 8.4 Favourite satellite channels 35 1.3 Rental videos 4 8.5 Lock satellite channels 36 1.4 Social networks 4 8.6 Satellite installation 37 1.5 Ambilight+hue 4 8.7 Problems with satellites 40 1.6 Skype 5 1.7 Smartphones and tablets 5 9 Home menu 42 1.8 Pause TV and recordings 5 1.9 Gaming 5 10 TV guide 43 1.10 EasyLink 5 10.1 What you need 43 10.2 Using the TV guide 43 2 Setting up 7 10.3 Recordings 43 2.1 Read safety 7 2.2 TV stand and wall mounting 7 11 Sources 44 2.3 Tips on placement 7 11.1 Sources list 44 2.4 Power cable 7 11.2 From standby 44 2.5 Antenna cable 8 11.3 EasyLink 44 2.6 Satellite dish 8 12 Timers and clock 45 3 Network 9 12.1 Sleeptimer 45 3.1 Wireless network 9 12.2 Clock 45 3.2 Wired network 10 12.3 Switch off timer 45 3.3 Network settings 10 13 3D 46 4 Connections 12 13.1 3D 46 4.1 Tips on connections 12 13.2 What you need 46 4.2 EasyLink HDMI CEC 13 13.3 The 3D glasses 46 4.3 Common interface - CAM 14 13.4 Care of the 3D glasses 47 4.4 Set-top box - STB 15 13.5 Watch 3D 47 4.5 Satellite receiver 15 13.6 Optimal 3D viewing 48 4.6 Home Theatre System - HTS 15 13.7 Health warning 48 4.7 Blu-ray Disc player 17 14 Games 49 4.8 DVD player 17 4.9 Game console 17 14.1 Play a game 49 4.10 USB Hard Drive 18 14.2 Two-player games 49 4.11 USB keyboard or mouse 19 15 Your photos, videos and music 51 4.12 USB -

Tuesday 18.04.17

PaulPaul MasonMason NuNuclearuclc eaar wwawarmongersarmmonongeg rss HadleyHadley FreemaFreemann BBe mmoreorore lillikeikee DDylanylylann WWishish YYouou WWereere HHereere HHoHoww theythhey mademadade itit How Donald Trump becamebecame the golfer-in-chief The course at the president’s Mar-a-Lago estate, Palm Beach Tuesday 18.04.17 12A Shortcuts (Clockwise from main) Frank Bruno, Ellie Goulding and gnd Prince Harry Sport pion Duke McKenzie as part of the charity initiative Heads How boxing Together , which he instigated with his brother, William, and the can be good Duchess of Cambridge. for the soul While that entry-level intro- duction to the sport is some way distant from the rigours of boxing that Bruno endured, he would f it takes a prince to aalertlert recognise the process. I the nation to the safety-ety- Bruno has done much to raise valve powers of boxingng in awareness of bipolar disorder coping with mental stress – as and it took a lot for him to admit Prince Harry has done thiss week that the eff ects of his illness – Frank Bruno, who has rubbedubbed were exacerbated as much by the shoulders with royalty andd mental as well as the physical struggled with mental healthalth demands of his trade. issues, will surely lead thee Bruno said he had never felt so applause. alive as in the immediate after- The former world heavy-y- math of winning the title against weight champion, now 55, Oliver McCall in London in 1995. has been sectioned three Nor had he ever been so alone : times since he retired in 1996996 on top of the world at last after and came perilously closee to three failed attempts – but not being institutionalised forr for long, he suspected. -

SATURDAY 16 DECEMBER 06:00 Breakfast 10:00

SATURDAY 16 DECEMBER 06:00 Breakfast All programme timings UK All programme timings UK All programme timings UK 10:00 Saturday Kitchen Live 09:25 ITV News 09:50 Black-ish 06:00 Forces News 11:30 Nigel Slater's 12 Tastes of Christmas 09:30 Saturday Morning with James Martin 10:15 Made in Chelsea 06:30 The Forces Sports Show 12:00 Football Focus 11:20 Gino's Italian Coastal Escape 11:05 The Real Housewives of Cheshire 07:00 Flying Through Time 13:00 BBC News 11:50 Countrywise 11:55 Funniest Falls, Fails & Flops 07:30 The Aviators 13:15 Sports Personality of the Year 2017 - The 12:20 Thunderbirds Are Go 12:20 Star Trek: Voyager 08:00 Sea Power Contenders 12:45 ITV News 13:05 Shortlist 08:30 America's WWII 14:15 Bargain Hunt 12:55 Endeavour 13:10 Malcolm in the Middle 09:00 America's WWII 15:15 Escape to the Country 14:55 The Flintstones in Viva Rock Vegas 13:35 Malcolm in the Middle 09:30 America's WWII 16:00 Final Score 16:35 The Chase 14:00 The Big Bang Theory 10:00 The Forces Sports Show 17:25 BBC News 17:35 Paul O'Grady: For the Love of Dogs 14:20 The Big Bang Theory 10:30 Hogan's Heroes 17:35 BBC London News 18:05 ITV News London 14:40 The Gadget Show 11:00 Hogan's Heroes 17:40 Pointless Celebrities 18:15 ITV News 15:30 Tamara's World 11:30 Hogan's Heroes 18:30 Strictly Come Dancing Final 18:30 The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey 16:25 The Middle 12:00 Hogan's Heroes 21:45 ITV News 16:45 Shortlist 12:30 Hogan's Heroes 22:00 The Hangover 16:50 The Big Bang Theory 13:00 Danger UXB Comedy about a group of friends who go to Las 17:15 The Big Bang Theory 14:00 Knight Rider Vegas for a bachelor party and wake up to a 17:35 Sanctuary 15:00 Knight Rider trashed hotel room, a missing groom and no 18:25 Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves 16:00 UFO recollection of the past night's 20:45 Shortlist 17:00 The Forces Sports Show events. -

Teletext Ltd …………………………………………………………………………………… ……

TELETEXT LTD …………………………………………………………………………………… …… 1 WHO IS TELETEXT LIMITED 1.1 Teletext Limited (Teletext) is a UK company providing on-screen information services principally aimed at consumers, comprising of up-to-the-minute, comprehensive content across multiple delivery platforms including analogue, satellite and digital terrestrial television, the PC internet, and mobile phones via SMS. 1.2 Teletext replaced 'Oracle' as the ITV public Teletext licensee starting broadcasting on the 1st of January 1993 and rapidly established itself as a household name. Available in over 81% of households, it is viewed by over 17 million people every week. Output from Teletext appears on ITV, Channel 4 and Channel 5. 1.3 In 1996, Teletext launched its website Teletext.co.uk that has had an average of 5 million monthly page impressions. 1.4 In 1997, Teletext launched its digital service that appeared on ITV digital (now Freeview), satellite (Sky) and until 2004, cable television. 1.5 In 2004 launched the Teletext Holidays Television Channel 1.6 In 2004 Teletext agreed a deal with Channel 4 to provide a commercial and editorial text service on Channel 4 digital 1.7 In March 2005 Teletext launched a classified car service. 1.8 In June 2005 Teletext began a new, 10-year deal with ITV, bringing its commercial and editorial text service to ITV's digital channels 1.9 Teletext content also appears on mobile phones, which includes SMS. A number of key Teletext content areas could be found on Teletext WAP services, including news, sport, finance and holidays between 2000 and 2002 when the service was dropped. -

Terris All Gold

Leeds Student Friday, F www.leedsstudent.org.uk Terris all Knowin' Owain gold But does the NUS They're not NME's, President know what they're ours we want? juice pages 1243 space pages 15 Housing con men hit campus Fraudsters impersonate Unipol officials to con house-hunters STUDENTS have been approached in the street by men pretending to be from a Unipol registered property manager. One group of students was approached at Leeds University's Parkinson steps by a man in a suit. who asked them it they were looking for a Unipol standard property. He then attempted to direct them to a non-Unipol agent. Another group was similarly approached in Headingley Lane. Steve Chippendale. Unipol's Code of Standards Officer, issued a general warning to students not to be taken in by these men. He said: "I urge students to check with Unipol whether agents are registered with us. 'These particular agents are not signed up to our Code of Standards. Please phone us or drop into the race if you are [insure." Steve is concerned that such acus ities will coerce students into signing for properties prematurely. He said: "These heavy handed tactics have been used in previous years and we do not want students to sign up for properties under false pretenses." He also stressed that most Unipol agents only advertise after March I. when their official list is published. Unipol could not name the agent involved, as the only concrete evidence they have at the moment is students phoning to complain about their experiences. -

Layout 1 (Page 1)

LOVE CRICKET? WWW. TITANSOF CRICKET. COM BUSINESS WITH PERSONALITY DON’T MISS IT! THE 50P ENGLAND TAKE GIANT STEP TAX DEBATE TOWARDS WORLD NO1 SPOT SHOULD THE COALITION SCRAP BRESNAN CRUSHES INDIA P22 & 23 THE TOP RATE? P8 Issue 1,437 Tuesday 2 August 2011 www.cityam.com FREE HSBC plans US PULLS BACK a jobs cull in Europe ▲ BANKING BY JULIET SAMUEL EUROPE is set to lose thousands of jobs FROM THE BRINK to higher-growth markets in Asia as HSBC slashes its headcount by 30,000 ▲ POLITICS in the next two years. BY ELIZABETH FOURNIER That includes 700 jobs cut in the UK alone in the first half of this year, with US POLITICIANS moved one step closer more to come as the bank refocuses its last night to approving an eleventh- business eastwards. It has also cut 700 hour deal to raise the country’s debt jobs in France, 1,400 in the US and 300 ceiling, and hope to avoid the prospect in the Middle East. of a default that would throw global By contrast, it has hired 1,500 in Asia- markets into chaos. Pacific and 800 in Brazil, although Members of the Republican-con- Latin America overall has seen 1,700 trolled House of Representatives voted jobs cut. 269-161 in favour of the proposed plan, The bank says that the numbers are which will lift the debt ceiling by $2.4 merely gross job cuts, with many likely trillion (£1.48 trillion) before the end of to go through “natural attrition”. But it the year through a programme of has no estimate for the net job losses spending cuts that politicians have expected in the UK or overall.