TELETEXT and ITS USE in SCHOOLS by GARY DAVID

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Managing the BBC's Estate

Managing the BBC’s estate Report by the Comptroller and Auditor General presented to the BBC Trust Value for Money Committee, 3 December 2014 BRITISH BROADCASTING CORPORATION Managing the BBC’s estate Report by the Comptroller and Auditor General presented to the BBC Trust Value for Money Committee, 3 December 2014 Presented to Parliament by the Secretary of State for Culture, Media & Sport by Command of Her Majesty January 2015 © BBC 2015 The text of this document may be reproduced free of charge in any format or medium providing that it is reproduced accurately and not in a misleading context. The material must be acknowledged as BBC copyright and the document title specified. Where third party material has been identified, permission from the respective copyright holder must be sought. BBC Trust response to the National Audit Office value for money study: Managing the BBC’s estate This year the Executive has developed a BBC Trust response new strategy which has been reviewed by As governing body of the BBC, the Trust is the Trust. In the short term, the Executive responsible for ensuring that the licence fee is focused on delivering the disposal of is spent efficiently and effectively. One of the Media Village in west London and associated ways we do this is by receiving and acting staff moves including plans to relocate staff upon value for money reports from the NAO. to surplus space in Birmingham, Salford, This report, which has focused on the BBC’s Bristol and Caversham. This disposal will management of its estate, has found that the reduce vacant space to just 2.6 per cent and BBC has made good progress in rationalising significantly reduce costs. -

ENG ME 566 Advanced Engineering Mathematics Instructor: M

Fall 2011 ME 566 Advanced Engineering Mathematics ENG ME 566 Advanced Engineering Mathematics Instructor: M. S. Howe EMA 218 (730 Commonwealth Ave) [email protected] Prerequisites: Multivariate Calculus; Ordinary Differential Equations; or instructor permission. It is expected that you can already: • solve simple first and second order linear ordinary differential equations • differentiate and integrate elementary functions, including trigonometric, exponential and hyperbolic functions • integrate by parts; evaluate simple surface and volume integrals • use the binomial theorem and the series expansions of elementary functions (sine, cosine, exponential, logarithmic and hyperbolic functions) • do all the problems in the prerequisites self test at the end of these notes. Course Outcomes: • consolidate understanding of vector calculus and applications to graduate level engi- neering • introductory understanding of complex variable theory with applications to engineering problems • ability to solve standard partial differential equations of engineering science using eigen- function expansions, Fourier transforms and generalised functions • become proficient in documenting calculations Textbook: Lectures are based on Mathematical Methods for Mechanical Sciences (M. S. Howe; 6th edition). It can be downloaded in pdf form from the ME 566 BlackBoard web site. You are expected to ‘read around’ the subject, and are recommended to consult other textbooks such as those listed on page 5. Course grading: • 4 take-home examinations (12.5% each) • final closed book examination (50%) Fall 2011 1 ME 566 Advanced Engineering Mathematics Fall 2011 ME 566 Advanced Engineering Mathematics Homework: Four ungraded homework assignments provide practice in applying techniques taught in class – model answers will be posted on BlackBoard. In addition there are four take home exams each consisting of a short essay and 5 problems. -

East Tower Inspiration Page 6

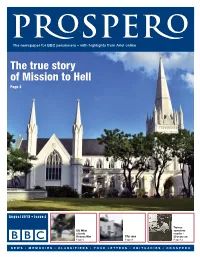

The newspaper for BBC pensioners – with highlights from Ariel online East Tower inspiration Page 6 AUGUST 2014 • Issue 4 TV news celebrates Remembering Great (BBC) 60 years Bing Scots Page 2 Page 7 Page 8 NEWS • MEMORIES • CLASSIFIEDS • YOUR LETTERS • OBITUARIES • CROSPERO 02 BACK AT THE BBC TV news celebrates its 60th birthday Sixty years ago, the first ever BBC TV news bulletin was aired – wedged in between a cricket match and a Royal visit to an agriculture show. Not much has changed, has it? people’s childhoods, of people’s lives,’ lead to 24-hour news channels. she adds. But back in 1983, when round the clock How much!?! But BBC TV news did not evolve in news was still a distant dream, there were a vacuum. bigger priorities than the 2-3am slot in the One of the original Humpty toys made ‘A large part of the story was intense nation’s daily news intake. for the BBC children’s TV programme competition and innovation between the On 17 January at 6.30am, Breakfast Time Play School has sold at auction in Oxford BBC and ITV, and then with Channel 4 over became the country’s first early-morning TV for £6,250. many years,’ says Taylor. news programme. Bonhams had valued the 53cm-high The competition was evident almost ‘It was another move towards the sense toy at £1,200. immediately. The BBC, wary of its new that news is happening all the time,’ says The auction house called Humpty rival’s cutting-edge format, exhibited its Hockaday. -

The True Story of Mission to Hell Page 4

The newspaper for BBC pensioners – with highlights from Ariel online The true story of Mission to Hell Page 4 August 2015 • Issue 4 Trainee Oh! What operators a lovely reunite – Vietnam War TFS 1964 50 years on Page 6 Page 8 Page 12 NEWS • MEMORIES • CLASSIFIEDS • YOUR LETTERS • OBITUARIES • CROSPERO 02 BACK AT THE BBC Departments Annual report highlights ‘better’ for BBC challenge move to Salford The BBC faces a challenge to keep all parts of the audience happy at the same time as efficiency targets demand that it does less. said that certain segments of society were more than £150k and to trim the senior being underserved. manager population to around 1% of But this pressing need to deliver more and the workforce. in different ways comes with a warning that In March this year, 95 senior managers Delivering Quality First (DQF) is set to take a collected salaries of more than £150k against bigger bite of BBC services. a target of 72. The annual report reiterates that £484m ‘We continue to work towards these of DQF annual savings have already been targets but they have not yet been achieved,’ achieved, with the BBC on track to deliver its the BBC admitted, attributing this to ‘changes Staff ‘loved the move’ from London to target of £700m pa savings by 2016/17. in the external market’ and the consolidation Salford that took place in 2011 and The first four years of DQF have seen of senior roles into larger jobs. departments ‘are better for it’, believes Peter Salmon (pictured). a 25% reduction in the proportion of the More staff licence fee spent on overheads, with 93% of Speaking four years on from the biggest There may be too many at the top, but the the BBC’s ‘controllable spend’ now going on ever BBC migration, the director, BBC gap between average BBC earnings and Tony content and distribution. -

Agreement Between the Government of the Republic of Kazakhstan, The

AGREEMENT Between the Government of the Republic of Kazakhstan, the Government of the Kyrgyz Republic and the Government of the Republic of Uzbekistan on Cooperation in the Area of Environment and Rational Nature Use The Governments of the participating countries of the Agreement hereinafter referred to as the Parties, Guided by the Treaty on Eternal Friendship between the Republic of Kazakhstan, the Kyrgyz Republic and the Republic of Uzbekistan, signed in Bishkek, January 10, 1997; Attaching great significance to environmental protection and rational use of the natural resources and desiring to obtain practical results in this field by means of effective cooperation; Realistically estimating potentialities of ecological dangers in the context of unfavorable natural climatic and hydrometeorological conditions, and acknowledging these problems as the common tasks; Recognizing the great importance of protection and improvement of the environmental situation, prudent and zealous use of natural resources for effectuation of economic and social development with due regard to the interests of the living and future generations; Expressing confidence that cooperation while solving common problems in the environmental protection in each of the countries meets their mutual advantage; and Desiring thereafter to promote the international efforts through this cooperation, aimed at protection and improvement of the environment and rational use of natural resources as the basis of the sound development on the global and regional levels; Have agreed as follows: Article I The Parties shall develop cooperation in the area of environmental protection and rational use of natural resources on the basis of equality of rights, mutual benefit pursuant to the Laws of the respective Countries. -

Wakefield 2006 RISC OS Computer Show

I would like to welcome you all to this, our eleventh annual show in Wakefield. There have been many ups and downs over the last eleven years, since the first show at Cedar Court, organised in thirteen weeks, which ended up taking over the entire hotel. Ever since then, we have been at our current venue of Thornes Park. Over the years we have had many interesting attractions and features, such as the guest appearance by Johnny Ball one year. Of course, the show has seen many new hardware and software launches and previews over the years, some more successful then others: Kinetic, Peanut, Phoebe, StrongARM, Vantage, RiScript and so on. In fact, this year it is ten full years since we saw the very first StrongARM at the first Wakefield Show, as well as being the 25th Anniversary of the BBC Micro! Even now, we still have people developing for this famous microcomputer, which helped to start the home computer revolution. Be sure to visit both the JGH BBC Software and Domesday System stands during your visit. The Domesday Project is another superb example of how advanced we were with the BBC Master and other Acorn products of the 1980s. Now we are looking to the future with the new A9home, which is expected to be on retail sale or available for ordering at the show. Over the years we have had visitors to the show from all over the world, from countries such as New Zealand, Australia, South Africa, Belgium, Finland, Sweden and the USA; not bad for an amateur show! Another long-standing attraction of the show is of course the charity stall, which allows redundant equipment to be recycled, and through your kind support the stall has raised many thousands of pounds, primarily for the Wakefield Hospice, over the years. -

Archimedes PC Emulator

Archimedes PC Emulator PC emulators are not new, but so far they have had limited success in their job of enabling your chosen micro to run PC-compatible software. Simon Jones unveils Acorns PC Emulator package for the Archimedes range of micros to see how well it performs in action. At this years PCW Show, Acorn proudly displayed its PC Emulator package for the Archimedes range of computers, which is claimed to allow packages written for the IBM PC to run on an Archimedes. Acorn was demonstrating the Emulator running dBase III+ and Lotus 1-2-3 at the show and, as I only managed a quick glance at the Emulator then, I was pleased to get the opportunity to examine the product at close quarters. Having seen other attempts at PC compatibility, such as pc-ditto (reviewed in PCW, October) I was sceptical to say the least. The Archimedes carries on the Acorn tradition, having a lot in common with the BBC Micro and the BBC Master series. Indeed, the Archimedes will run most of the well-behaved software written for the BBC computers. However, the Archimedes and the BBC micros differ radically in the CPU they use and the amount of RAM available. Based on Acorns RISC processor, the Archimedes 440 is blindingly fast and, with 4Mbytes of memory, it is not short functions to those in MS-DOS. This is cellaneous keys between the main of space — a problem which caused the more than a little confusing if you are group and the numerics. The back- downfall of the BBC Micros. -

Acorn Master Service Manual

British Broadcasting Corporation Master Series Microcomputer Service Manual British Broadcasting Corporation Master Series Microcomputer Service Manual Part No 0443,004 Issue 1 April 1986 M S S M W BBC ' B B C. C A C L 1986 N the whole or any part of the information contained , or the product described , this manual may be adapted or reproduced in any material form except with the prior written approval of A C L (A C). T product described in this manual and products for use with , are subject to continuous development and . A information of a technical nature and particulars of the product and its use ( including the information and particulars in this ) are given by A C in good . H, it is acknowledged that there may be errors or omissions in this . A list of details of any amendments or revisions to this manual can be obtained upon request from A C T E. A C welcome . A :- T E A C L N R C CB5 8PD A maintenance and service on the product must be carried out by A C authorised . A C can accept no liability whatsoever for any loss or damage caused by service or maintenance by unauthorised . T manual is intended only to assist the reader in the use of this , and therefore A C shall not be liable for any loss or damage whatsoever arising from the use of any information or particulars , or any error or omission , this , or any incorrect use of the . T A C . F 1986 P A C L 1 I 1 M S S M WARNING: THE COMPUTER MUST BE EARTHED IMPORTANT: T : G Y E B N B L T moulded plug must be used with the fuse and fuse carrier firmly in . -

BBC Chair Role Spec

Chair, BBC We are looking for an outstanding individual with demonstrable leadership skills and a passion for the media and public broadcasting, to represent the public interest in the BBC and maintain the Corporation's independence. As per the BBC Royal Charter, the Chair of the BBC Board must be appointed by Order in Council following a fair and open competition. The Governance Code, including the public appointment principles, must be followed in making the appointment. The Commissioner for Public Appointments will ensure that the appointment is made in accordance with the Governance Code. Candidates should be aware that the preferred candidate for the post of Chair will be required to appear before a Parliamentary Select Committee prior to appointment. About the BBC The BBC’s mission is defined by Royal Charter: to act in the public interest, serving all audiences through the provision of impartial, high-quality and distinctive output and services which inform, educate and entertain. The BBC is required to do this through delivering five public purposes: 1. To provide impartial news and information to help people understand and engage with the world around them; 2. To support learning for people of all ages; 3. To show the most creative, highest quality and distinctive output and services; 4. To reflect, represent and serve the diverse communities of all of the United Kingdom’s nations and regions and, in doing so, support the creative economy across the United Kingdom; and, 5. To reflect the United Kingdom, its culture and values to the world. The BBC is a public corporation, independent in all matters concerning the fulfilment of its mission and the promotion of the public purposes. -

Acorn User Display at the AAUG Stand During Will Be Featuring Denbridge Digital the RISC OS '99 Show at Epsom Race in More Depth in a Future Issue of the Course

eD6st-§elling RISC OS magazine in the world 4^:^^ i I m Find out what Rf| ::j!:azj achines can do tau ISSUE 215 CHRISTMAS 1999 £4.20 1 1 1 1 1! House balls heavy (packol 10) £15 illSJ 640HS Media lot MO dri.c £|9 £!2J]| Mouse lor A7000/r- N/C CD 630t1B re-wriie niedia £10 fii.rs £S tS.il Mouse for all Aciirns (not etr) A70DQ CD 630MB vrriie once raedis (Pk ol Computers for Education £12 II4.II1 10) £|0 £11.15 Original mouse for all Atoms (not A7K) HARDWARE i £16 urn JAZ IGB midta £58 £68.15 Business and Home |AZ 2GB media PERIPHERALS £69 [i PD 630MS media SPECIAL OFFER! £18 tll.lS I Syid 1.5GB media £S8 £S!IS ISDN MODEM + FREE Syquest lOSMB media £45 [S28I ACORN A7000+ tOHniTERS FIXING K. SytfuestOiMB media £45 islSjl INTERNET CONNEaiON )f[|iit'iij![IMB media £45 tS2S slice lor ,!.:., 2d Rlst PC int 1 waj L jj) i( 1 Syqufit 770HB media £76 £45 (Sji? I A?000 4. Ciasm [D £499 hard drive liting kir 2x 64k bpi ehaniiels mil M IDE £|2 £14.10 Zip lOOHBraetfia £8 (Ml IS9xU0«40mm A7000+(l3isnhO £449 W.il i- baikplane (not il CO aJrody insialled) Zip mW £34 [3).!S iOOMB media 1; pack) £35 awl] ;;! footprint A71100+0(lyHeyCD £549 mil Fixing km for hard drives ^ £S ff.40 Zip2S0HBmedia £11.50 (I4.i .Wf^ »«* 2 analogue ports |aTODCH- Odysse)- Nmotk HoniiDr cable lor all £525 mm Acorn (lelecdon) £|0 fll iS | 30 I- Odyssey Primary £599 flOJ ai Podule mi lor A3D00 £|6 RISC OS UPGRADES 47000 I OdyssEc Setoiidary £599 Rise PC I slo[ backplane ISP trial mm ii4.B I Argonet I £29 A700Oi Rise OS 3.11 chip sti £20 am OdyssEr^uil £699 Lih.il SCSI I S II [abteclioice -

I Am Mediacityuk

Useful information Events Cycle Contacts I am MediaCityUK is easy to MediaCityUK is a new Commercial office space: reach by bike and there waterfront destination for 07436 839 969 are over 300 cycle bays Manchester with digital [email protected] dotted across our site. creativity, learning and The Studios: MediaCityUK leisure at its heart. We host 0161 886 5111 a wide range of exciting Eat and drink studiobookings@ events: mediacityuk.co.uk/ We have a wide selection of dock10.co.uk destination/whats-on more than 40 venues for you The Pie Factory: to choose from. To find out 0161 660 3600 Getting here more visit: mediacityuk.co.uk/ [email protected] destination/eat-and-drink Road and parking Apartments: Two minutes from the 0161 238 7404 Manchester motorway Shopping anita.jolley@ network via Junctions 2 The Lowry Outlet at mediacityuk.co.uk and 3 of the M602. We have MediaCityUK is home to Hotel: 6,000 secure car parking a range of designer, high 0845 250 8458 spaces at key locations street and individual brands reservations@ across MediaCityUK. Sat offering discounts of up to himediacityuk.co.uk nav reference: M50 2EQ. 70%. lowryoutlet.co.uk Serviced apartments: 0161 820 6868 Tram reservations@ There are tram stops at Studio audiences theheartapartments.co.uk MediaCityUK, Broadway The Studios, MediaCityUK, and Harbour City and it are operated by dock10. General: takes just 15 minutes to To find out more details 0161 886 5300 get to Manchester city on tickets for shows go to: [email protected] centre for all inter-city mediacityuk.co.uk/studios/ connections. -

Who Saysyou Can't Improve on Thebest?

Who says you can’t improve on the best? The Best. Better. Since the day it was launched the BBC Micro has Above is a machine which at first glance looks been garlanded with praise. very like the best micro in Britain. One early reviewer called it `the limousine of home But it’s better. computers’ and virtually every independent assessment It’s the new, enhanced, BBC Micro B+. of it since has added weight to that description. Now you can have the legendary quality and The reasons are legion. reliability of the B, plus an extra 32K memory. First, its famous adaptability and expandability. And since this extra memory is largely used on the A feature which makes the BBC Micro invaluable in screen it allows wider use of the outstanding graphics. every corner of science, industry and education. You also get an additional two expansion ROM Then there are its exceptional graphics; its speed; sockets (making four available ROM sockets in all). its reliability. In other words, room for more applications And of course its language - BBC Basic, which and languages. today is the leading language in education and widely The acclaimed Acorn disc filing system is used in business and industry. included as standard for immediate access to a fast and All in all, quite simply, the best. efficient disc storage system. There are extra utility commands for disc and ROM management-thus maximising memory availability. And remember, the Model B+, like the B, is produced by Acorn Computers who have an unbeaten record for products of outstanding quality and reliability.