A Reading of Thakazhi Sivasankara Pillai's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Study on the Tribal Struggle in the Novel Kocharethi” Is the Record of Genuine Research Work Done by Me Under the Guidance of Ms

The Voice of the Unheard: A Study on the Tribal Struggle in the Novel Kocharethi Project submitted to the Mahatma Gandhi University Kottayam in partial recognition of the requirements for the award of the Degree of Bachelor of Arts in English Language and Literature (Model II – Teaching) Benal Benny Register Number: 170021017769 Sixth Semester Department of English St. Paul’s College Kalamassery 2017-2020 Declaration I do hereby declare that the project “The Voice of the unheard: A Study on the Tribal Struggle in the Novel Kocharethi” is the record of genuine research work done by me under the guidance of Ms. Rosy Milna, Assistant Professor, Department of English, St. Paul’s College, Kalamassery. Benal Benny Certificate This is to certify that the project work “The Voice of the Tribal Struggle n the novel Kocharethi” is a record of the original work carried out by Benal Benny under the supervision and guidance of Ms. Rosy Milna, Assistant Professor, Department of English, St. Paul’s College, Kalamassery. Dr. Salia Rex Ms. Rosy Milna Head of the Deparment Project Guide Department of English Department of English St. Paul’s College St. Paul’s College Kalamassery Kalamassery Acknowledgement I would like to thank Ms. Rosy Milna for her assistance and suggestions during the writing of this project. This work would not have taken its present shape without her painstaking scrutiny and timely interventions. I thank Dr. Salia Rex, Head of Department of English for her suggestions and corrections. I would also thank my friends, teachers and the librarian for their assistance and support. -

Mist: an Analytical Study Focusing on the Theme and Imagery of the Novel

[ VOLUME 5 I ISSUE 3 I JULY– SEPT 2018] E ISSN 2348 –1269, PRINT ISSN 2349-5138 Mist: An Analytical Study Focusing on the Theme and Imagery of the Novel *Arya V. Unnithan Guest Lecturer, NSS College for Women, Karamana, Trivandrum, Kerala Received: May 23, 2018 Accepted: June 30, 2018 ABSTRACT Mist, the Malayalam novel is certainly a golden feather in M.T. Vasudevan Nair’s crown and is a brilliant work which has enhanced Malayalam literature’s fame across the world. This novel is truly different from M.T.’s other writings such as Randamuzham or its English translation titled Bhima. M.T. is a writer with wonderfulnarrative skills. In the novel, he combined his story- telling power with the technique of stream- of- consciousness and thereby provides readers, a brilliant reading experience. This paper attempts to analyse the novel, with special focus on its theme and imagery, thereby to point out how far the imagery and symbolism agrees with the theme of the novel. Keywords: analysis-theme-imagery-Vimala-theme of waiting- love and longing- death-stillness Introduction: Madath Thekkepaattu Vasudevan Nair, popularly known as M.T., is an Indian writer, screenplay writer and film director from the state of Kerala. He is a creative and gifted writer in modern Malayalam literature and is one of the masters of post-Independence Indian literature. He was born on 9 August 1933 in Kudallur, a village in the present day Pattambi Taluk in Palakkad district. He rose to fame at the age of 20, when he won the prize for the best short story in Malayalam at World Short Story Competition conducted by the New York Herald Tribune. -

Love and Marriage Across Communal Barriers: a Note on Hindu-Muslim Relationship in Three Malayalam Novels

Love and Marriage Across Communal Barriers: A Note on Hindu-Muslim Relationship in Three Malayalam Novels K. AYYAPPA PANIKER If marriages were made in heaven, the humans would not have much work to do in this world. But fornmately or unfortunately marriages continue to be a matter of grave concern not only for individuals before, during, and/ or after matrimony, but also for social and religious groups. Marriages do create problems, but many look upon them as capable of solving problems too. To the poet's saying about the course of true love, we might add that there are forces that do not allow the smooth running of the course of true love. Yet those who believe in love as a panacea for all personal and social ills recommend it as a sure means of achieving social and religious integration across caste and communal barriers. In a poem written against the backdrop of the 1921 Moplah Rebellion in Malabar, the Malayalam poet Kumaran Asan presents a futuristic Brahmin-Chandala or Nambudiri-Pulaya marriage. To him this was advaita in practice, although in that poem this vision of unity is not extended to the Muslims. In Malayalam fi ction, however, the theme of love and marriage between Hindus and Muslims keeps recurring, although portrayals of the successful working of inter-communal marriages are very rare. This article tries to focus on three novels in Malayalam in which this theme of Hindu-Muslim relationship is presented either as the pivotal or as a minor concern. In all the three cases love flourishes, but marriage is forestalled by unfavourable circumstances. -

Language and Literature

1 Indian Languages and Literature Introduction Thousands of years ago, the people of the Harappan civilisation knew how to write. Unfortunately, their script has not yet been deciphered. Despite this setback, it is safe to state that the literary traditions of India go back to over 3,000 years ago. India is a huge land with a continuous history spanning several millennia. There is a staggering degree of variety and diversity in the languages and dialects spoken by Indians. This diversity is a result of the influx of languages and ideas from all over the continent, mostly through migration from Central, Eastern and Western Asia. There are differences and variations in the languages and dialects as a result of several factors – ethnicity, history, geography and others. There is a broad social integration among all the speakers of a certain language. In the beginning languages and dialects developed in the different regions of the country in relative isolation. In India, languages are often a mark of identity of a person and define regional boundaries. Cultural mixing among various races and communities led to the mixing of languages and dialects to a great extent, although they still maintain regional identity. In free India, the broad geographical distribution pattern of major language groups was used as one of the decisive factors for the formation of states. This gave a new political meaning to the geographical pattern of the linguistic distribution in the country. According to the 1961 census figures, the most comprehensive data on languages collected in India, there were 187 languages spoken by different sections of our society. -

Women at Crossroads: Multi- Disciplinary Perspectives’

ISSN 2395-4396 (Online) National Seminar on ‘Women at Crossroads: Multi- disciplinary Perspectives’ Publication Partner: IJARIIE ORGANISE BY: DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH PSGR KRISHNAMMAL COLLEGE FOR WOMEN, PEELAMEDU, COIMBATORE Volume-2, Issue-6, 2017 Vol-2 Issue-6 2017 IJARIIE-ISSN (O)-2395-4396 A Comparative Study of the Role of Women in New Generation Malayalam Films and Serials Jibin Francis Research Scholar Department of English PSG College of Arts and Science, Coimbatore Abstract This 21st century is called the era of technology, which witnesses revolutionary developments in every aspect of life. The life style of the 21st century people is very different; their attitude and culture have changed .This change of viewpoint is visible in every field of life including Film and television. Nowadays there are several realty shows capturing the attention of the people. The electronic media influence the mind of people. Different television programs target different categories of people .For example the cartoon programs target kids; the realty shows target youth. The points of view of the directors and audience are changing in the modern era. In earlier time, women had only a decorative role in the films. Their representation was merely for satisfying the needs of men. The roles of women were always under the norms and rules of the patriarchal society. They were most often presented on the screen as sexual objects .Here women were abused twice, first by the male character in the film and second, by the spectators. But now the scenario is different. The viewpoint of the directors as well as the audience has drastically changed .In this era the directors are courageous enough to make films with women as central characters. -

Colonial Rule in Kerala and the Development of Malayalam Novels: Special Reference to the Early Malayalam Novels

RESEARCH REVIEW International Journal of Multidisciplinary 2021; 6(2):01-03 Research Paper ISSN: 2455-3085 (Online) https://doi.org/10.31305/rrijm.2021.v06.i02.001 Double Blind Peer Reviewed/Refereed Journal https://www.rrjournals.com/ Colonial Rule in Kerala and the Development of Malayalam Novels: Special Reference to the Early Malayalam Novels *Ramdas V H Research Scholar, Comparative Literature and Linguistics, Sree Sankaracharya University of Sanskrit, Kalady ABSTRACT Article Publication Malayalam literature has a predominant position among other literatures. From the Published Online: 14-Feb-2021 ‘Pattu’ moments it had undergone so many movements and theories to transform to the present style. The history of Malayalam literature witnessed some important Author's Correspondence changes and movements in the history. That means from the beginning to the present Ramdas V H situation, the literary works and literary movements and its changes helped the development of Malayalam literature. It is difficult to estimate the development Research Scholar, Comparative Literature periods of Malayalam literature. Because South Indian languages like Tamil, and Linguistics, Sree Sankaracharya Kannada, etc. gave their own contributions to the development of Malayalam University of Sanskrit, Kalady literature. Especially Tamil literature gave more important contributions to the Asst.Professor, Dept. of English development of Malayalam literature. The English education was another milestone Ilahia College of Arts and Science of the development of Malayalam literature. The establishment of printing presses, ramuvh[at]gmail.com the education minutes of Lord Macaulay, etc. helped the development process. People with the influence of English language and literature, began to produce a new style of writing in Malayalam literature. -

Translation, Religion and Culture

==================================================================== Language in India www.languageinindia.com ISSN 1930-2940 Vol. 19:1 January 2019 India’s Higher Education Authority UGC Approved List of Journals Serial Number 49042 ==================================================================== Translation, Religion and Culture T. Rubalakshmy =================================================================== Abstract Translation is made for human being to interact with each other to express their love, emotions and trade for their survival. Translators often been hidden into unknown characters who paved the road way for some contribution. In the same time being a translator is very hard and dangerous one. William Tyndale he is in Holland in the year 1536 he worked as a translating the Bible into English. Human needs to understand the culture of the native place where they live. Translator even translates the text and speak many languages. Translators need to have a good knowledge about every language. Translators can give their own opinion while translating. In Malayalam in the novel Chemmeen translated in English by Narayanan Menon titled Chemmeen. This paper is about the relationship between Karuthamma and Pareekutty. Keywords: Chemmeen, translation, languages, relationship, culture, dangerous. Introduction Language is made for human beings. Translating is not an easy task to do from one language to another. Translation has its long history. While translating a novel we have different cultures and traditions. We need to find the equivalent name of a word in translating language. The language and culture are entwined and inseparable Because in many books we have a mythological character, history, customs and ideas. So we face a problem like this while translating a work. Here Thakazhi Sivasankara Pillai also face many problems during translating a work in English . -

Tribal, Cultural Identity and Development in Narayan's Kocharethi

www.TLHjournal.com Literary Herald ISSN: 2454-3365 An International Refereed English e-Journal Impact Factor: 2.24 (IIJIF) Tribal, Cultural Identity and Development in Narayan’s Kocharethi - The Arya Woman Pramod Kumar Gond Research Scholar Department of English Banaras Hindu University Abstract It is widely seen that Indian society is vast and complex including multiple communities and cultures. The tribals are the most important contributors towards the origin of the Indian society. But due to lack of education, documented history and awareness, their culture has been misinterpreted and assimilated with others under the label of development. It pulls them at periphery and causes the identity crisis. In this article I focused on tribal who are facing a serious identity crisis despite its rich cultural legacy. This study is related to cultural issues, the changes, the reasons and the upliftment of tribal culture with a special reference to the Malayarayar tribes portrayed in Narayan‟s Kocherethi. Key Words: Tribal, Culture, Identity, Development and assimilations. Vol. 2, Issue 4 (March 2017) Dr. Siddhartha Sharma Page 449 Editor-in-Chief www.TLHjournal.com Literary Herald ISSN: 2454-3365 An International Refereed English e-Journal Impact Factor: 2.24 (IIJIF) Tribal, Cultural Identity and Development in Narayan’s Kocharethi - The Arya Woman Pramod Kumar Gond Research Scholar Department of English Banaras Hindu University The conflict between cultural identity and development is major issue in tribal society that is emerging as a focal consideration in modern Indian literary canon. The phrases „Culture‟ and „development‟ which have not always gone together, or been worked upon within the same context. -

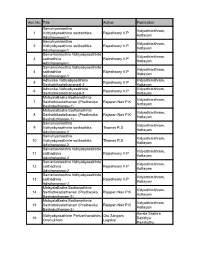

Library Stock.Pdf

Acc.No. Title Author Publication Samuhyashasthra Vidyarthimithram, 1 Vidhyabyasathinte saithadhika Rajeshwary V.P Kottayam Adisthanangal-1 Samuhyashasthra Vidyarthimithram, 2 Vidhyabyasathinte saithadhika Rajeshwary V.P Kottayam Adisthanangal-1 Samaniashasthra Vidhyabyasathinte Vidyarthimithram, 3 saithadhika Rajeshwary V.P Kottayam Adisthanangal-1 Samaniashasthra Vidhyabyasathinte Vidyarthimithram, 4 saithadhika Rajeshwary V.P Kottayam Adisthanangal-1 Adhunika Vidhyabyasathinte Vidyarthimithram, 5 Rajeshwary V.P Saithathikadisthanangal-2 Kottayam Adhunika Vidhyabyasathinte Vidyarthimithram, 6 Rajeshwary V.P Saithathikadisthanangal-2 Kottayam MalayalaBasha Bodhanathinte Vidyarthimithram, 7 Saithathikadisthanam (Pradhesika Rajapan Nair P.K Kottayam Bashabothanam-1) MalayalaBasha Bodhanathinte Vidyarthimithram, 8 Saithathikadisthanam (Pradhesika Rajapan Nair P.K Kottayam Bashabothanam-1) Samuhyashasthra Vidyarthimithram, 9 Vidhyabyasathinte saithadhika Thomas R.S Kottayam Adisthanangal-2 Samuhyashasthra Vidyarthimithram, 10 Vidhyabyasathinte saithadhika Thomas R.S Kottayam Adisthanangal-2 Samaniashasthra Vidhyabyasathinte Vidyarthimithram, 11 saithadhika Rajeshwary V.P Kottayam Adisthanangal-2 Samaniashasthra Vidhyabyasathinte Vidyarthimithram, 12 saithadhika Rajeshwary V.P Kottayam Adisthanangal-2 Samaniashasthra Vidhyabyasathinte Vidyarthimithram, 13 saithadhika Rajeshwary V.P Kottayam Adisthanangal-2 MalayalaBasha Bodhanathinte Vidyarthimithram, 14 Saithathikadisthanam (Pradhesika Rajapan Nair P.K Kottayam Bashabothanam-2) MalayalaBasha -

Issn 2454-8596

ISSN 2454-8596 www.vidhyayanaejournal.org An International Multidisciplinary Research e-Journal ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- NARAYAN’S KOCHARETHI IN THE LIGHT OF POST- COLONIALISM Hardik Udeshi Assistant Professor Department of English Christ College, Rajkot Dr. Paresh Joshi Assistant Professor Department of English Christ College, Rajkot V o l u m e I II I s s u e 6 J u n e - 2 0 1 8 Page 1 ISSN 2454-8596 www.vidhyayanaejournal.org An International Multidisciplinary Research e-Journal ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ABSTRACT British people have colonized almost whole world. Colonies were made and those people were convicted in different ways. The present paper proceeds from the conviction that post colonialism and ecocriticism have a great deal to gain from one another. The paper attempts to see with the perspective of how Adivasis, tribes in general are colonized not only with other people but with the people of themselves. The changes associated with globalization have led to the rapid extension and intensification of capital along with an acceleration of the destruction of the environment and a growing gap between the rich and the poor. Narayan in his novel Kocharethi shows how Malayaras are colonized with their land, customs, and traditions and with their identities. The paper will focus on the reading of novel with post-colonial perspective. Keywords: Colonization, Post Colonialism, Forest, Adivasis V o l u m e I II I s s u e 6 J u n e - 2 0 1 8 Page 2 ISSN 2454-8596 www.vidhyayanaejournal.org An International Multidisciplinary Research e-Journal ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- History notes that the world has made into colonies by British people. -

Research Scholar an International Refereed E-Journal of Literary Explorations

ISSN 2320 – 6101 Research Scholar www.researchscholar.co.in An International Refereed e-Journal of Literary Explorations ASSERTING LOCAL TEXTURE THROUGH SOCIAL NETWORKING Surya Kiran Ph.D. Scholar Department of English University of Hyderabad, (A.P.) Ngugi Wa Thiong’O in his famous essay “The Language of African Literature” has pointed out the adverse impacts of the colonizers language and culture on that of the colonized. After the withdrawal of the colonizers from the land, not many people preferred to preserve and develop the ancestral language and impart it to the next generation. Instead, the colonizers language takes over and mastering the foreigner’s language had by then been established as the key to climbing the charts of social status. This resulted in the development of a “look down up on” attitude towards the regional literatures. This phenomenon is found more in South India, Kerala in particular where English learning has taken importance over Malayalam. The importance given to Dan Brown or J.K. Rowling over Vaikkom Muhammad Basheer or Thakazhi Shivashankara Pillai is not the real concern here, but the fact that there are no many writers in the present day scenario who manage to get past the overwhelming influence of foreign writers using the flavour of regional literature. Globalisation which had brought the English language so close to ordinary people through internet played a crucial role in this development. Blogging and social networking made the English literary arena familiar to one and all and gradually took over the regional writing. Ironically, some excellent pieces of dialectic writing are found in blogs. -

Malayalam - Novel

NEW BOMBAY KERALEEYA SAMAJ , LIBRARY LIBRARY LIST MALAYALAM - NOVEL SR.NO: BOOK'S NAME AUTHOR TYPE 4000 ORU SEETHAKOODY A.A.AZIS NOVEL 4001 AADYARATHRI NASHTAPETTAVAR A.D. RAJAN NOVEL 4002 AJYA HUTHI A.N.E. SUVARNAVALLY NOVEL 4003 UPACHAPAM A.N.E. SUVARNAVALLY NOVEL 4004 ABHILASHANGELEE VIDA A.P.I. SADIQ NOVEL 4005 GREEN CARD ABRAHAM THECKEMURY NOVEL 4006 TARSANUM IRUMBU MANUSHYARUM ADGAR RAICE BAROSE NOVEL 4007 TARSANUM KOLLAKKARUM ADGAR RAICE BAROSE NOVEL 4008 PATHIMOONNU PRASNANGAL AGATHA CHRISTIE D.NOVEL 4009 ABC NARAHATHYAKAL AGATHA CHRISTIE D.NOVEL 4010 HARITHABHAKALKK APPURAM AKBAR KAKKATTIL NOVEL 4011 ENMAKAJE AMBIKA SUDAN MANGAD NOVEL 4012 EZHUTHATHA KADALAS AMRITA PRITAM NOVEL 4013 MARANA CERTIFICATE ANAND NOVEL 4014 AALKKOOTTAM ANAND NOVEL 4015 ABHAYARTHIKAL ANAND NOVEL 4016 MARUBHOOMIKAL UNDAKUNNATHU ANAND NOVEL 4017 MANGALAM RAHIM MUGATHALA NOVEL 4018 VARDHAKYAM ENDE DUKHAM ARAVINDAN PERAMANGALAM NOVEL 4019 CHORAKKALAM SIR ARTHAR KONAN DOYLE D.NOVEL 4020 THIRICHU VARAVU ASHTAMOORTHY NOVEL 4021 MALSARAM ASHWATHI NOVEL 4022 OTTAPETTAVARUDEY RATHRI BABU KILIROOR NOVEL 4023 THANAL BALAKRISHNAN NOVEL 4024 NINGAL ARIYUNNATHINE BALAKRISHNAN MANGAD NOVEL 4025 KADAMBARI BANABATTAN NOVEL 4026 ANANDAMADAM BANKIM CHANDRA CHATTERJI NOVEL 4027 MATHILUKAL VIKAM MOHAMMAD BASHEER NOVEL 4028 ATTACK BATTEN BOSE NOVEL 4029 DR.DEVIL BATTON BOSE D.NOVEL 4030 CHANAKYAPURI BATTON BOSE D.NOVEL 4031 RAKTHA RAKSHASSE BRAM STOCKER NOVEL 4032 NASHTAPETTAVARUDEY SANGAGANAM C.GOPINATH NOVEL 4033 PRAKRTHI NIYAMAM C.R.PARAMESHWARAN NOVEL 4034 CHUZHALI C.RADHAKRISHNAN NOVEL 4035 VERUKAL PADARUNNA VAZHIKAL C.RADHAKRISHNAN NOVEL 4036 ATHIRUKAL KADAKKUNNAVAR C.RADHAKRISHNAN NOVEL 4037 SAHADHARMINI C.RADHAKRISHNAN NOVEL 4038 KAANAL THULLIKAL C.RADHAKRISHNAN NOVEL 4039 POOJYAM C.RADHAKRISHNAN NOVEL 4040 KANGALIKAL C.RADHAKRISHNAN NOVEL 4041 THEVADISHI C.RADHAKRISHNAN NOVEL 4042 KANKALIKAL C.RADHAKRISHNAN NOVEL 4043 MRINALAM C.RADHAKRISHNAN NOVEL 4044 KANNIMANGAKAL C.RADHAKRISHNAN NOVEL 4045 MALAKAMAAR CHIRAKU VEESHUMBOL C.V.