Daniel Levy the Voice of the Piano, and More

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Program Notes | Yannick and Manny

23 Season 2018-2019 Thursday, November 29, at 7:30 The Philadelphia Orchestra Friday, November 30, at 8:00 Saturday, December 1, Yannick Nézet-Séguin Conductor at 8:00 Emanuel Ax Piano Brahms Piano Concerto No. 2 in B-flat major, Op. 83 I. Allegro non troppo II. Allegro appassionato III. Andante—Più adagio—Tempo I IV. Allegretto grazioso—Un poco più presto Intermission Brown Perspectives United States premiere Dvořák Symphony No. 7 in D minor, Op. 70 I. Allegro maestoso II. Poco adagio III. Scherzo: Vivace IV. Finale: Allegro This program runs approximately 2 hours, 5 minutes. The November 29 concert is sponsored by Elia D. Buck and Caroline B. Rogers. The November 29 concert is also sponsored by the Louis N. Cassett Foundation. The November 30 concert is sponsored by Alexandra Edsall and Robert Victor. The December 1 concert is sponsored by Medcomp. Philadelphia Orchestra concerts are broadcast on WRTI 90.1 FM on Sunday afternoons at 1 PM, and are repeated on Monday evenings at 7 PM on WRTI HD 2. Visit www.wrti.org to listen live or for more details. 24 Please join us following the November 30 and December 1 concerts for a free Organ Postlude featuring Peter Richard Conte. Brahms Prelude, from Prelude and Fugue in G minor Brahms Fugue in A-flat minor Dvořák/transcr. Conte Humoresque, Op. 101, No. 7 Widor Toccata, from Organ Symphony No. 5 in F minor, Op. 42, No. 1 The Organ Postludes are part of the Fred J. Cooper Memorial Organ Experience, supported through a generous grant from the Wyncote Foundation. -

Cds by Composer/Performer

CPCC MUSIC LIBRARY COMPACT DISCS Updated May 2007 Abercrombie, John (Furs on Ice and 9 other selections) guitar, bass, & synthesizer 1033 Academy for Ancient Music Berlin Works of Telemann, Blavet Geminiani 1226 Adams, John Short Ride, Chairman Dances, Harmonium (Andriessen) 876, 876A Adventures of Baron Munchausen (music composed and conducted by Michael Kamen) 1244 Adderley, Cannonball Somethin’ Else (Autumn Leaves; Love For Sale; Somethin’ Else; One for Daddy-O; Dancing in the Dark; Alison’s Uncle 1538 Aebersold, Jamey: Favorite Standards (vol 22) 1279 pt. 1 Aebersold, Jamey: Favorite Standards (vol 22) 1279 pt. 2 Aebersold, Jamey: Gettin’ It Together (vol 21) 1272 pt. 1 Aebersold, Jamey: Gettin’ It Together (vol 21) 1272 pt. 2 Aebersold, Jamey: Jazz Improvisation (vol 1) 1270 Aebersold, Jamey: Major and Minor (vol 24) 1281 pt. 1 Aebersold, Jamey: Major and Minor (vol 24) 1281 pt. 2 Aebersold, Jamey: One Dozen Standards (vol 23) 1280 pt. 1 Aebersold, Jamey: One Dozen Standards (vol 23) 1280 pt. 2 Aebersold, Jamey: The II-V7-1 Progression (vol 3) 1271 Aerosmith Get a Grip 1402 Airs d’Operettes Misc. arias (Barbara Hendricks; Philharmonia Orch./Foster) 928 Airwaves: Heritage of America Band, U.S. Air Force/Captain Larry H. Lang, cond. 1698 Albeniz, Echoes of Spain: Suite Espanola, Op.47 and misc. pieces (John Williams, guitar) 962 Albinoni, Tomaso (also Pachelbel, Vivaldi, Bach, Purcell) 1212 Albinoni, Tomaso Adagio in G Minor (also Pachelbel: Canon; Zipoli: Elevazione for Cello, Oboe; Gluck: Dance of the Furies, Dance of the Blessed Spirits, Interlude; Boyce: Symphony No. 4 in F Major; Purcell: The Indian Queen- Trumpet Overture)(Consort of London; R,Clark) 1569 Albinoni, Tomaso Concerto Pour 2 Trompettes in C; Concerto in C (Lionel Andre, trumpet) (also works by Tartini; Vivaldi; Maurice André, trumpet) 1520 Alderete, Ignacio: Harpe indienne et orgue 1019 Aloft: Heritage of America Band (United States Air Force/Captain Larry H. -

Itunes Store and Spotify Recordings

A+ Music Memory 2016-2017 iTunes Store and Spotify Recordings Bach Pachelbel Canon and Other Baroque Favorites, track 12, Suite No. 2 in B Minor, BWV1067: Badinerie (James Galway, Zagreb Soloists & I Solisti di Zagreb, Universal International BMG Music, 1978). iTunes: https://itunes.apple.com/us/album/pachelbel-canon-other- baroque/id458810023 Spotify: https://open.spotify.com/track/4bFAmfXpXtmJRs2t5tDDui Bartók Bartók: Hungarian Pictures – Weiner: Hungarian Folk Dance – Enescu: Romanian Rhapsodies, track 2, Magyar Kepek (Hungarian Sketches), BB 103: No. 2. Bear Dance (Neeme Järvi & Philharmonia Orchestra, Chandos, 1991). iTunes: https://itunes.apple.com/us/album/bartok-hungarian-pictures/id265414807 Spotify: https://open.spotify.com/track/5E4P3wJnd2w8Cv1b37sAgb Beethoven Beethoven: Piano Sonatas Nos. 8, 14, 23 & 26, track 6, Piano Sonata No. 8 in C Minor, Op. 13 – “Pathétique,” III. Rondo (Allegro), (Alfred Brendel, Universal International Music B.V., 2001) iTunes: https://itunes.apple.com/us/album/beethoven-piano-sonatas- nos./id161022856 Spotify: https://open.spotify.com/track/2Z0QlVLMXKNbabcnQXeJCF Brahms Best of Brahms, track 11, Waltz No. 15 in A-Flat Minor, Op. 59 [Note: This track is mis-named: the piece is in A-Flat Major, from Op. 39] (Dieter Goldmann, SLG, LLC, 2009). iTunes: https://itunes.apple.com/us/album/best-of-brahms/id320938751 Spotify: https://open.spotify.com/track/1tZJGYhVLeFODlum7cCtsa A+ Mu Me ory – Re or n s of Clarke Trumpet Tunes, track 2, Suite in D Major: IV. The Prince of Denmark’s March, “Trumpet Voluntary” (Stéphane Beaulac and Vincent Boucher (ATMA Classique, 2006). iTunes: https://itunes.apple.com/us/album/trumpet-tunes/id343027234 Spotify: https://open.spotify.com/track/7wFCg74nihVlMcqvVZQ5es Delibes Flower Duet from Lakmé, track 1, Lakmé, Act 1: Viens, Mallika, … Dôme épais (Flower Duet) (Dame Joan Sutherland, Jane Barbié, Richard Bonynge, Orchestre national de l’Opéra de Monte-Carlo, Decca Label Group, 2009). -

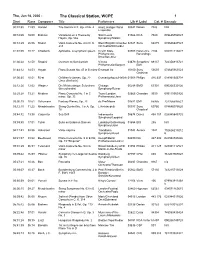

The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title Performerslib # Label Cat

Thu, Jun 18, 2020 - The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title PerformersLIb # Label Cat. # Barcode 00:01:30 11:59 Handel Trio Sonata in F, Op. 2 No. 4 Heinz Holliger Wind 00341 Denon 7026 N/A Ensemble 00:14:2918:00 Brahms Variations on a Theme by Saint Louis 01966 RCA 7920 078635792027 Haydn, Op. 56a Symphony/Slatkin 00:33:29 26:06 Mozart Violin Concerto No. 4 in D, K. Stern/English Chamber 02925 Sony 66475 074646647523 218 Orchestra/Schneider 01:01:0528:17 Chadwick Aphrodite, a symphonic poem Czech State 03308 Reference 2104 030911210427 Philharmonic, Recordings Brno/Serebrier 01:30:2212:50 Rossini Overture to Semiramide Vienna 03679 Seraphim/ 69137 724356913721 Philharmonic/Sargent EMI 01:44:1214:53 Haydn Piano Sonata No. 47 in B minor Emanuel Ax 10100 Sony 53635 074645363523 Classical 02:00:3510:51 Bizet Children's Games, Op. 22 Concertgebouw/Haitink 01008 Philips 416 437 028941643728 (Jeux d'enfants) 02:12:2612:02 Wagner Die Meistersinger: Selections Chicago 05288 BMG 63301 090266330126 (for orchestra) Symphony/Reiner 02:25:2833:21 Medtner Piano Concerto No. 1 in C Tozer/London 02666 Chandos 9039 095115903926 minor, Op. 33 Philharmonic/Jarvi 03:00:1910:51 Schumann Fantasy Pieces, Op. 73 du Pre/Moore 09531 EMI 65955 724356595521 03:12:1031:22 Mendelssohn String Quintet No. 1 in A, Op. L'Archibudelli 05537 Sony 60766 074646076620 18 Classical 03:44:32 13:38 Carpenter Sea Drift Indianapolis 08678 Decca 458 157 028945845725 Symphony/Leppard 03:59:4017:01 Tubin Suite on Estonian Dances Lubotsky/Gothenburg 01654 BIS 286 N/A Symphony/Jarvi 04:17:41 02:56 Halvorsen Valse caprice Trondheim 01943 Aurora 1921 702626219212 Symphony/Ruud 6 04:21:3738:22 Beethoven Piano Concerto No. -

Presentazione Standard Di Powerpoint

The History www.fazioli.com The History www.fazioli.com 1944–1977 Paolo Fazioli was born in Rome in 1944, into a family of furniture makers. From a very early age he demonstrated a gift for music and a keen interest in the piano. He consequently started taking piano lessons and continued his piano studies thorough his high school and university years, during which he developed a keen interest in the piano construction technology, broadening his knowledge by visiting manufacturing and restoration workshops and reading the most authoritative literature on the subject. In 1969, he graduated from the University of Rome with a degree in Mechanical Engineering and in 1971 he received a degree in piano performance from the G. Rossini Conservatory in Pesaro, under the guidance of Maestro Sergio Cafaro. At the same time, he earned a Master’s degree in Music Composition at the St Cecilia Academy in Rome, where he studied under the composer Boris Porena. In the meantime, his elder brothers took over the family business, manufacturing office The FAZIOLI family in 1947 furniture and exporting it throughout the world under the brand of MIM (Mobili Italiani Moderni). The Turin factory specialised in the production of metal furniture, while the Sacile factory (in the province of Pordenone) manufactured wood furniture using rare and exotic woods such as teak, mahogany and rosewood. 1944–1977 Paolo Fazioli joined the company after graduation, honing his management skills as a production planning manager first in Rome and then at the Turin factory, while at the same time developing his expertise in wood processing. -

4961168-37E111-714439855628.Pdf

Alexander Scriabin (1872-1915) Daniel Levy, piano 24 PRELUDES OP. 11 01. No.1 in C Major: Vivace 0’ 57” 02. No.2 in A Minor: Allegretto 1’ 57” 03. No.3 in G Major: Vivo 1’ 02” 04. No.4 in E Minor: Lento 2’ 00” 05. No.5 in D Major: Andante cantabile 1’ 46” 06. No.6 in B Minor: Allegro 0’ 56” 07. No.7 in A Major: Allegro assai 1’ 28” 08. No.8 in F Sharp Minor: Allegro agitato 1’ 40“ 09. No.9 in E Major: Andantino 1’ 43” 10. No.10 in C Sharp Minor: Andante 1’ 26” 11. No.11 in B Major: Allegro assai 2’ 03” 12. No.12 in G Sharp Minor: Andante 1’ 27” 13. No.13 in G Flat Major: Lento 1’ 30” 14. No.14 in E Flat Minor: Presto 1’ 02” 15. No.15 in D Flat Major: Lento 1’ 54” 16. No.16 in B Flat Minor: Misterioso 1’ 49” 17. No.17 in A Flat Major: Allegretto 0’ 40” 18. No.18 in F Minor: Allegro agitato 0’ 56” 19. No.19 in E Flat Major: Affettuoso 2’ 01” 20. No.20 in C Minor: Appassionato 1’ 12” 21. No.21 in B Flat Major: Andante 1’ 23” 22. No.22 in G Minor: Lento 1’ 17” 23. No.23 in F Major: Vivo 0’ 39” 24. No.24 in D Minor: Presto 0’ 55” 25. ÉTUDE IN C MINOR OP. 2, NO. 1 3’ 18” 12 ÉTUDES OP. 8 26. No.1 in C Sharp Minor: Allegro 1’ 43” 27. -

Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy Foundation

Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy Foundation Information July/August 2011 President Maestro Kurt Masur honoured Award ceremony in Paris The German Foreign Ministry and the French Ministry of Foreign & European Affairs have chosen Maestro Kurt Masur and Professor Pierre Boulez as winners of the Adenauer- de Gaulle Prize in 2011. On 20 June 2011 the Prize was formally bestowed at a ceremony in the Hôtel de Beauharnais, the Residence of the German Ambassador in Paris, by the two Ministers responsible for Franco- German co-operation, French Europe Minister Laurent Wauquiez and the German friendship. The artistic careers of Pierre Boulez and Kurt Masur – for- Minister of State in the German Fo- med through many years of experience in Germany and France – are an exam- reign Office Dr Werner Hoyer. ple of the creativity and originality which the values of the European commu- nity have produced.” declared Minister of State Dr Hoyer. “In the French con- The Adenauer-de Gaulle Prize, ductor and composer Pierre Boulez and the German conductor Kurt Masur, this which was established on 22 January year we are honouring two personalities who, through their professional as 1988, is a distinction for those people well as private commitment, have made an extraordinary contribution to Fran- who have made an especial contribu- co-German relations. Both have worked tirelessly for many years in the neigh- tion to Franco-German co-operation. It bouring country. Kurt Masur was in charge of the “Orchestre National de France” is named after the former German from 2002 to 2008. Pierre Boulez, who had already conducted in Germany in Federal Chancellor Konrad Adenauer the 1950s and 1960s, has for many years worked together with the Berlin and the former President of the French Philharmonic Orchestra.” Republic Charles de Gaulle. -

Daniel Levy the Voice of the Piano, and More

12 ROBERT SCHUMANN (1810 - 1856) Lieder on poems by Heinrich Heine 1 Abends Am Strand Op 45 No. 3 3’ 12” 2 “Du bist wie eine Blume” Op 25 (Myrthen) No. 24 1’ 49” 3 “Die Lotosblume” Op 25 (Myrthen) No. 7 1’ 50” 4 “Die beiden Grenadiere” Op 49. No. 1 3’ 31” Liederkreis Op. 24 5 No. 1 “Morgens steh' ich auf und frage” 0‘ 55” 6 No. 2 “Es treibt mich hin, es treibt ich her!” 1’ 07” 7 No. 3 “Ich wandelte unter den Bäumen” 3’ 45” 8 No. 4 “Lieb' Liebchen, leg's Händchen” 0’ 44” 9 No. 5 “Schöne Wiege meiner Leiden” 3’ 42” 10 No. 6 “Warte, warte, wilder Schismann” 1’ 44” 11 No. 7 “Berg’ und Burgen schaun herunter’” 3’ 42” 12 No. 8 “Anfangs wollt' ich fast verzagen” 0’ 56” 13 No. 9 “Mit Myrten und Rosen lieblich und hold” 4’ 02” Lieder on poems by Nikolaus Lenau Op. 90 14 No. 1 Lied eines Schmiedes 1’ 22” 15 No. 2 Meine Rose 3’ 29” 16 No. 3 Kommen und Scheiden 1’ 25” 17 No. 4 Die Sennin 2’ 21” 18 No. 5 Einsamkeit 2’ 51” 19 No. 6 Der schwere Abend 1’ 51” Lieder on poems by Emanuel Geibel 20 Geständnis Op. 74 No. 7 1‘ 40” 21 “Tief im Herzen trag ich Pein” Op. 138 No. 2 2’ 17” 22 “Weh, wie zornig ist das Mädchen” Op. 138 No. 7 1‘ 20” 23 “O wie liebllich ist das Mädchen” Op. 138 No. 3 2’ 04” 24 “Romanze” Op. 138 No. -

Music – Our Passion

2011 recent releases and highlights for piano Music – Our Passion. Hal Leonard is proud to be exclusive U.S. distributor for the distinguished Munich-based music publisher G. Henle Verlag. Henle Urtext editions are highly regarded for impeccable research of composers’ manuscripts, proofs, first editions and other relevant sources. Henle editions are universally praised for: • authoritative musical accuracy • the world’s highest quality music engraving • insightful critical commentary • helpful fingerings • premium, custom made paper • long-lasting binding for a lifetime of use Among the world’s leading classical pianists who have endorsed, performed and recorded Henle Urtext editions are: Leif Ove Andsnes • Vladimir Ashkenazy • Paul Badura-Skoda • Daniel Barenboim • Alfred Brendel • Rudolf Buchbinder • Philippe Entremont • Marc-André Hamelin • Vladimir Horowitz • Evgeny Kissin • Lang Lang • Elisabeth Leonskaja • Yundi Li • Gerhard Oppitz • Murray Perahia • András Schiff • Grigory Sokolov • Mitsuko Uchida • Lars Vogt REcent Urtext Editions for Piano Urtext editions FRÉDÉRIC CHOPIN: PIANO ROBERT SCHUMANN: SEVEN are softcover SONATA IN C MINOR, OP. 4 PIANO PIECES IN FUGHETTA unless clothbound is indicated. 51480942 ..................................................... $17.95 FORM, OP. 126 FRÉDÉRIC CHOPIN: POLONAISE 51480907 ..................................................... $13.95 Search description, IN A-FLAT MAJOR, OP. 53 ROBERT SCHUMANN: THREE contents, editors, REVISED EDITION PIANO SONATAS FOR THE and all available Henle publications -

Müller Vs Schubert in Der Leiermann Brian Chapman ([email protected])

A WINTERREISE HYPOTHETICAL: Müller vs Schubert in Der Leiermann Brian Chapman ([email protected]) In the twenty-four poems of Wilhelm Müller’s Die Winterreise the protagonist gives expression to no fewer than twenty-six questions. According to the ordering of the poems in Franz Schubert’s Winterreise song cycle, the first twenty-four of these questions are scattered among twelve of the first twenty-one songs and are rhetorical in nature, being addressed by the protagonist either to himself or to the world at large. These questions reflect the thoughts and feelings of the jilted lover, being focussed first on self-pity (Nos. 1-13) and then on the desire for death (Nos. 14-23). In the final poem – No.24 Der Leiermann (The Hurdy-Gurdy Man) – there is a total shift in the poetic psychology. Whereas the first twenty-three songs give expression to a self-absorbed psychopathological journey entirely void of human contact – and almost void of any living creature at all save for occasional references to barking dogs, hostile ravens, a fond memory of a lark and nightingale engaged in competitive song, and a portentous crow – No.24 is devoted completely to the woeful plight of someone other than the protagonist. For the first time in the entire cycle, the protagonist focusses on the pathetic situation of another human being – a pitiful, lonely hurdy-gurdy man to whom nobody listens, from whom everyone averts his or her gaze, and whose little plate is always empty as stray dogs growl around him, thus: 24. The Hurdy-Gurdy Man1 Stands an organ-grinder No one likes to hear him, There outside the town, No one looks his way, Plays as best he can though And around the old man Fingers stiff have grown. -

Documents Sur Robert SCHUMANN (1810-1856)

DOCUMENTS SUR Robert SCHUMANN (1810-1856) (Mise à jour le 21 mai 2013) Médiathèque Musicale Mahler 11 bis, rue Vézelay – F-75008 Paris – (+33) (0)1.53.89.09.10 www.mediathequemahler.org Médiathèque Musicale Mahler – Robert Schumann 2010 2 Livres et documents sur Robert SCHUMANN (1810-1856) LIVRES 3 Sur Robert Schumann 3 Schumann dans les biographies d'autres compositeurs… 10 Schumann dans les ouvrages thématiques… 13 PARTITIONS 22 ENREGISTREMENTS SONORES 34 Schumann dans les disques d'autres compositeurs 75 REVUES 99 ARCHIVES NUMÉRISÉES 100 FONDS D'ARCHIVES 101 Médiathèque Musicale Mahler – Robert Schumann 2010 3 LIVRES BIOGRAPHIES DE ROBERT SCHUMANN Clara und Robert Schumann : Zeitgenössische Porträts : Katalog zur Ausstellung des Heinrich-Heine- Instituts, Düsseldorf und des Robert-SChumann-Hauses in Zwickau (7. Juni - 24. Juli 1994, Heinrich- Heine-Institut, Düsseldorf...) / Vorwort von Joseph A. Kruse. - Düsseldorf : Droste, 1994. (BM SCHUM A5) Robert Schumann / préf. de J.C. Teboul. - Paris : Place, 2004. (BM SCHUM E4) Robert Schumann : the autograph manuscript of the piano concerto in a minor op. 54 : [catalogue de vente, Sotheby's, 22 novembre 1989]. - London : Sotheby's, 1989. (BM SCHUM G Concerto) Schumann. - Paris : Hachette, 1970. (BM SCHUM D6) Schumann à la Grange de Meslay du 10 au 19 juin 1994 : 31e Fêtes musicales en Touraine, 1994. - Tours : Fêtes Musicales en Touraine, 1994. (BM SCHUM A4) Thematisches Verzeichniss sämmtlicher im Druck erschienenen Werke Robert Schumann's. - Leipzig ; New York : Schuberth & Co, s.d.. (BM SCHUM A1) ABERT Hermann. - Robert Schumann. - Berlin : Harmonie, 1903. (BM SCHUM C ABE A1) ABRAHAM Gerald. - Schumann : a symposium. - London : Oxford University Press, 1952. -

Daniel Levy, Piano

A Piano Recital for the World’s Children Daniel Levy, piano CLAUDE DEBUSSY 1 La fille aux cheveux de lin. Prélude No. 8. Premier livre. 2’ 35” Children‘s Corner 2 Doctor Gradus ad Parnassum 2’ 15” 3 Jimbo’s Lullaby 3’ 42” 4 Serenade for the doll 2’ 40” 5 The snow is dancing 3’ 11” 6 The little shepherd 2‘ 23“ 7 Golliwogg’s cake walk 3‘ 12“ 8 Rêverie 3’ 56” MAURICE RAVEL 9 Pavane pour une infante défunte 6’ 22” ROBERT SCHUMANN Unpublished Pieces from ‘Album for the Young’ Op. 68 10 The doll‘s lullaby 0’ 24” 11 Fragment 0’ 54” 12 The hiding cuckoo 1’ 01” 13 Rebus 0’ 41” 14 Bear Dance 0’ 38” 15 A little piece by Mozart 0’ 50“ 16 A famous melody by Beethoven 0’ 45” FELIX MENDELSSSOHN BARTHOLDY Sechs Kinderstücke Op. 72 17 Allegro non troppo 1’ 21” 18 Andante sostenuto 1’ 39” 19 Allegretto 0’ 55” 20 Andante con moto 1‘ 10” 21 Allegro assai 1’ 26” 22 Vivace 1‘ 31” FRANZ LISZT 23 Hymne de l'enfant à son réveil 6’ 52” No. 6 from the ‘Harmonies poétiques et religieuses’ ROBERT SCHUMANN 24 Impromptu No. 4 from 'Bilder aus Osten' Op. 66, four hands 2 ’14” Kinderszenen Op. 15 25 Of foreign lands and people 1’ 34” 26 Curious story 1‘ 13“ 27 Catch me 0’ 28” 28 The suppliant child 0’ 50” 29 Happiness 0’ 47” 30 An important event 0’ 51” 31 Rêverie 2’ 45” 32 By the fireside 0’ 53” 33 Ride a cock horse 0’ 45” 34 Almost too serious 1’ 40” 35 Frightening 1’ 33” 36 Child falling asleep 1’ 32” 37 The Poet speaks 2’ 16” JOHANN SEBASTIAN BACH 38 Prelude No.