Memories of Kings Heath

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PDF995, Job 6

The Wildlife Trust for Birmingham and the Black Country _____________________________________________________________ The Endless Village Revisited Technical Background December 2005 Protecting Wildlife for the Future The Endless Village Revisited Technical Background 2005 The Wildlife Trust for Birmingham and the Black Country gratefully acknowledges support from English Nature, Dudley MBC, Sandwell MBC, Walsall MBC and Wolverhampton City Council. This Report was compiled by: Dr Ellen Pisolkar MSc IEEM The Endless Village Revisited Technical Background 2005 The Endless Village Revisited Technical Background 2005 Contents Page 1. INTRODUCTION 1 2. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 2 3. SITES 4 3.1 Introduction 4 3.2 Birmingham 3.2.1 Edgbaston Reservoir 5 3.2.2 Moseley Bog 11 3.2.3 Queslett Quarry 17 3.2.4 Spaghetti Junction 22 3.2.5 Swanshurst Park 26 3.3 Dudley 3.3.1 Castle Hill 30 3.3.2 Doulton’s Claypit/Saltwells Wood 34 3.3.3 Fens Pools 44 3.4 Sandwell 3.4.1 Darby’s Hill Rd and Darby’s Hill Quarry 50 3.4.2 Sandwell Valley 54 3.4.3 Sheepwash Urban Park 63 3.5 Walsall 3.5.1 Moorcroft Wood 71 3.5.2 Reedswood Park 76 3.5 3 Rough Wood 81 3.6 Wolverhampton 3.6.1 Northycote Farm 85 3.6.2 Smestow Valley LNR (Valley Park) 90 3.6.3 West Park 97 4. HABITATS 101 The Endless Village Revisited Technical Background 2005 4.1 Introduction 101 4.2 Heathland 103 4.3 Canals 105 4.4 Rivers and Streams 110 4.5 Waterbodies 115 4.6 Grassland 119 4.7 Woodland 123 5. -

Nature Week PDF SEND

SEND – 17th May 24th May 2021 How to Use this Resource Over the course of the summer term, Birmingham SGO’s will be running 4 themed weeks to support your school and young people. We encourage you to use the resources and activities in the best way for your school – feel free to share with colleagues, parents and carers and young people! If your school has social media or internal school platforms, please feel free to share the Birmingham School Games message! www.sgochallenge.com #backtoschoolgames SEND Challenge Sensory Challenges Being in the outdoors is beneficial to young people and adults. By being physically active outside, you can achieve positive benefits such as: These challenges will focus on sight, smell, sound, touch pattern making. - Physical fitness - Emotional wellbeing Find an area outside that is safe to walk in. - Reduced anxiety and stress - Improved self-esteem Choose one of the challenges every day this - Improved sleep week. More challenges can be found at https://www.sense.org.uk/ Can you complete all 5 activities before the end of the week? You can also access yoga activities by clicking on the link https://www.sense.org.uk/umbraco/surface/download/download? filepath=/media/2577/yogaresource_singlepagesforweb.pdf www.sgochallenge.com #backtoschoolgames 11 44 3 2 5 www.sgochallenge.com #backtoschoolgames Birmingham Local Parks ALDRIDGE ROAD AND RECREATION OAKLANDS RECREATION GROUND GROUND OLD YARDLEY PARK Check out our list of Birmingham ASTON PARK PERRY PARK parks! They are ideal to walk, cycle or BOURNBROOK WALKWAY ROOKERY PARK BROOKVALE PARK SARA PARK jog in. BURBURY BRICKWORKS RIVER WALK SELLY OAK PARK COCKS MOORS WOODS SHELDON PARK EDGBASTON RESERVOIR SHIRE COUNTRY PARK Being in the outdoors has been shown FOX HOLLIES PARK SMALL HEATH PARK to improve physical and emotional HANDSWORTH PARK SPARKHILL PARK HENRY BARBER PARK STETCHFORD HALL PARK wellbeing. -

Birmingham City Council Joint Cabinet Member and Chief

BIRMINGHAM CITY COUNCIL JOINT CABINET MEMBER AND CHIEF OFFICER WEDNESDAY, 21 MARCH 2018 AT 00:00 HOURS IN CABINET MEMBERS OFFICE, COUNCIL HOUSE, VICTORIA SQUARE, BIRMINGHAM, B1 1BB A G E N D A 1 REVIEW OF PARKS AND NATURE CONSERVATION 2018-19 FEES 3 - 18 AND CHARGES Assistant Director - Sport, Events, Open Spaces and Wellbeing 2 CONTRACT AWARD - INSURANCE RENEWALS EMPLOYERS 19 - 26 LIABILITY AND MOTOR POLICIES (P0432)- PUBLIC Item Description P R I V A T E A G E N D A 3 CONTRACT AWARD - INSURANCE RENEWALS EMPLOYERS LIABILITY AND MOTOR POLICIES (P0432)- PRIVATE Item Description Page 1 of 26 Page 2 of 26 Birmingham City Council BIRMINGHAM CITY COUNCIL PUBLIC REPORT Report to: CABINET MEMBER CLEAN STREETS, RECYCLING AND ENVIRONMENT JOINTLY WITH THE CORPORATE DIRECTOR - PLACE Report of: Assistant Director – Sport, Events, Open Spaces and Wellbeing Date of Decision: 20 March 2018 SUBJECT: REVIEW OF PARKS & NATURE CONSERVATION 2018/19 FEES AND CHARGES Key Decision: Yes / No Relevant Forward Plan Ref: N/A If not in the Forward Plan: Chief Executive approved (please "X" box) O&S Chair approved Relevant Cabinet Member(s) Councillor Lisa Trickett Relevant O&S Chair: Councillor Mohammed Aikhlaq, Corporate Resources and Governance Wards affected: 1. Purpose of report: 1.1 To seek approval to introduce revised Parks & Nature Conservation fees and charges with effect from 1st April 2018. 2. Decision(s) recommended: That the Cabinet Member for Clean Streets, Recycling and Environment and the Corporate Director - Place : 2.1 Approves the implementation of the proposed 2018/19 fees and charges as outlined in Appendix 1. -

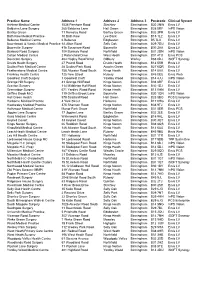

Practice Name

Practice Name Address 1 Address 2 Address 3 Postcode Clinical System Ashtree Medical Centre 1536 Pershore Road Stirchley Birmingham B30 2NW Emis LV Baldwins Lane Surgery 265 Baldwins Lane Hall Green Birmingham B28 0RF InPS Vision Bartley Green 71 Romsley Road Bartley Green Birmingham B32 3PR Emis LV Bath Row Medical Practice 10 Bath Row Lee Bank Birmingham B15 1LZ Emis LV Bellevue Medical Centre 6 Bellevue Edgbaston Birmingham B5 7LX Emis LV Bournbrook & Varsity Medical Practice 1A Alton Road Selly Oak Birmingham B29 7DU Emis LV Bournville Surgery 41b Sycamore Road Bournville Birmingham B30 2AA Emis LV Bunbury Road Surgery 108 Bunbury Road Northfield Birmingham B31 2DN InPS Vision Cofton Medical Centre 2 Robinsfield Drive West Heath Birmingham B31 4TU Emis PCS Dovecote Surgery 464 Hagley Road West Oldbury Warley B68 0DJ iSOFT Synergy Druids Heath Surgery 27 Pound Road Druids Heath Birmingham B14 5SB Emis LV Dudley Park Medical Centre 28 Dudley Park Road Acocks Green Birmingham B27 6QR Emis LV Featherstone Medical Centre 158 Alcester Road South Kings Heath Birmingham B14 6AA Emis LV Frankley Health Centre 125 New Street Rubery Birmingham B45 0EU Emis Web Goodrest Croft Surgery 1 Goodrest Croft Yardley Wood Birmingham B14 4JU InPS Vision Grange Hill Surgery 41 Grange Hill Road Kings Norton Birmingham B38 8RF Emis LV Granton Surgery 114 Middleton Hall Road Kings Norton Birmingham B30 1DJ Emis LV Greenridge Surgery 671 Yardley Wood Road Kings Heath Birmingham B13 0HN Emis LV Griffins Brook M.C 119 Griffins Brook Lane Bournville Birmingham -

West Midlands Police Freedom of Information

West Midlands Police Freedom of Information Property Name Address 1 Address 2 Street Locality Town County Postcode Tenure Type 16 Summer Lane 16 Summer Lane Newtown Birmingham West Midlands B19 3SD Lease Offices Acocks Green 21-27 Yardley Road Acocks Green Birmingham West Midlands B27 6EF Freehold Neighbourhood Aldridge Anchor Road Aldridge Walsall West Midlands WS9 8PN Freehold Neighbourhood Anchorage Road Annexe 35-37 Anchorage Road Sutton Coldfield Birmingham West Midlands B74 2PJ Freehold Offices Aston Queens Road Aston Birmingham West Midlands B6 7ND Freehold Offices Balsall Heath 48 Edward Road Balsall Heath Birmingham West Midlands B12 9LR Freehold Neighbourhood Bell Green Riley Square Bell Green Coventry West Midlands CV2 1LR Lease Neighbourhood Billesley 555 Yardley Wood Road Billesley Birmingham West Midlands B13 0TB Freehold Neighbourhood Billesley Fire Station Brook Lane Billesley Birmingham West Midlands B13 0DH Lease Neighbourhood Bilston Police Station Railway Street Bilston Wolverhampton West Midlands WV14 7DT Freehold Neighbourhood Bloxwich Station Street Bloxwich West Midlands WS3 2PD Freehold Police Station Bournville 341 Bournville Lane Bournville Birmingham West Midlands B30 1QX Lease Police Station Bradford Street Bradford Street Digbeth Birmingham West Midlands B12 0JB Freehold Offices Brierley Hill Bank Street Brierley Hill West Midlands DY5 3DH Freehold Police Station Broadgate House Room 217 Broadgate House Broadgate Coventry West Midlands CV1 1NH License Neighbourhood Broadway School BO Aston Campus, Broadway -

Birmingham Park Ranger Events

BIRMINGHAM PARK RANGER EVENTS July - December 2014 Be Active Out & About All Events are listed on our website - www.birmingham.gov.uk/parks July 2014 Thursday 3rd July Volunteer Day Edgbaston Reservoir 10:30am – 1pm Join our regular team of volunteers on a range of practical work on various sites. Meet at Rangers Office, 115 Reservoir Road, Edgbaston B16 9EE. Saturday 5th July Grasshoppers & Crickets Newhall Valley Country Park 11am - 1pm Come and join the Rangers in the meadows of Newhall Valley to learn more about some of the insects that make the grassland their home. Please wear suitable footwear. Please book in advance. Meet at the car park off Wylde Green Road, Sutton Coldfield, B76 1QT. Friday 11th July 10:30am until Saturday 12th July 4pm BioBlitz Sutton Park Become a ‘Citizen Scientist’ and help your National Nature Reserve. Our BioBlitz will be a 30hr event to record in detail, the animals and plants of Sutton Park. A variety of experts, specialists and generalists will be on site to guide you through a range of activities designed to record the wildlife within Sutton Park. For further details go to www.facebook.com/SPBB13 . Meet at the Visitor Centre, Park Road, Sutton Coldfield, B74 2YT. Sunday 13th July Bittel Reservoir Circular Walk Lickey Hills Country Park 11am – 2pm This is approx. a 5 mile walk mainly off road, hilly and uneven terrain with steps. Wear suitable outdoor clothing and footwear, bring water and a snack and your hat and sun cream if it’s scorching! Meet at Lickey Hills Visitors Centre, Warren Lane B45 8ER. -

14A. Private Harold Freeman Wood

Private Harold Freeman Wood Figure 1: (Above left) Japanned tin tea tray, black lacquer and gilt made in Birmingham (Above right) The Japanese lacquer tree Toxicodendron vernicifluum Harold’s father, Robert Wood was born around 1853. He was an ornamental japanner by trade. Japanning is a type of finish that originated as a European imitation of an Asian lacquer technique that used the dried sap of the Toxicodendron vernicifluum tree As the dried sap was unavailable in Europe, varnishes that had a resin base, similar to shellac were used which were applied in heat-dried layers and then polished, to give a smooth glossy finish. Experienced workers were in demand and well paid. Japanning was not a very safe operation. The risk of fire in the process of japanning must always have been great. We do not know for sure the effect the smoke and fumes had on workers, but Robert died in 1894, aged only forty-one.i Little is known about Robert’s early life, other than he was born in Worcester, and that, by the spring of 1881, he had relocated to Birmingham where he married Phoebe Alice Haywood, from Bilston, Staffordshire.ii They started married life at 14 Bordesley Park Road, Bordesley, Birmingham, where their first two children Laura and Nellie were born in 1881 and 1882. They were baptised together at Holy Trinity Church, Bordesley on 26th October 1882.iii By 1884 Robert and Phoebe had moved to 87 Wenman Street, Balsall Heath, Birmingham, where two further children, Hetty and Bertram Allen Wood were born.iv By the time twins, Jessica and Howard arrived on 6th April 1888 the family had moved again and were resident at 10 Islington Terrace, Balsall Heath. -

Name of Deceased

Date before which Name of Deceased Address, description and date of death of Names, addresses and descriptions of Persons to whom notices of claims are to be notices of claims "•(Surname first) ~ Deceased given and names, in parentheses, of Personal Representatives to be given NELSON, Dorothy ..'. Rose Court, 16 Oxford Road, Birkdale," South- Houghton & Co., 4 Park Road, Milnthorpe, Cumbria LA7 7AD, Solicitors. 31st August 1981 port PR8 2JR, Spinster. 25th May 1981. (Peter Henry Houghton and Ian Nigel Gunby.) (044) BUCHANAN, Mary . ' 79 Station Road, Herne Bay, Kent, Spinster. Paul Frederick Addis, 52-54 High Street, Whitstable, Kent or E. A. Barton, 21st August 1981 Margaret 1st June 1981. 52-54 High Street, Whitstable, Kent, Solicitors. (045) JONES, Phyllis Kathleen 1 Vernon Road, Stourport-on-Severn, Wife of Malcolm Davies & Co., 33 High Street, Kings Heath, Birmingham B14 7BB, 14th August 1981 Albert Jones. 23rd December 1980. Solicitors. (Tania Darville-Jones and Phillip Darville-Jones.) (285) HILL, Janet 50 Evergreen Road, Frimley, Camberley, Sur- Meadows & Co., 25 Monument Green, Weybridge, Surrey. (Harold Hill and 4th September 1981 rey, Estate Agents Manageress. 29th April Annie Knight.) (306) 1981. CHERRY, Maurice 29 Brentnall Drive, Sutton Coldfield, West Glaisyers, 254 Lichfield Road, Four Oaks, Sutton, Coldfield, West Midlands, 21st August 1981 Midlands, Engineer (Retired). 17th May Solicitors. (Rosemary Elizabeth Harrison.) (307) 1981. BRANDT, John Mowbray Alchornes, Nutley, Uckfield, East Sussex, Slaughter and May, 35 Basinghall Street, London EC2V 5DB. (William Rupert 20th August 1981 Company Director. 25th October 1980. Brandt and Caroline Margaret Brandt.) (046) WHITE, Minnie 7 Hawthorn Gardens, Forest Road, Broad- Biddle & Co., 1 Gresham Street, London EC2V 7BU. -

Birmingham City Council Planning Committee 14 March 2019

Birmingham City Council Planning Committee 14 March 2019 I submit for your consideration the attached reports for the South team. Recommendation Report No. Application No / Location / Proposal Approve - Subject to 9 2018/05638/PA 106 Legal Agreement Warwickshire County Cricket Ground Land east of Pershore Road and north of Edgbaston Road Edgbaston B5 Full planning application for the demolition of existing buildings and the development of a residential-led mixed use building containing 375 residential apartments (Use Class C3), ground floor retail units (Use Classes A1, A2, A3, A4 and A5), a gym (Use Class D2), plan, storage, residential amenity areas, site access, car parking, cycle parking, hard and soft landscaping and associated works, including reconfiguration of existing stadium car parking, security fence-line and spectator entrances, site access and hard and soft landscaping. residential amenity areas, site access, car parking, cycle parking, hard and soft landscaping and associated works, including reconfiguration of existing stadium car parking, security fence-line and spectator entrances, site access and hard and soft landscaping. Approve-Conditions 10 2019/00112/PA 45 Ryland Road Edgbaston Birmingham B15 2BN Erection of two and three storey side and single storey rear extensions Page 1 of 2 Director, Inclusive Growth Approve-Conditions 11 2018/06724/PA Land at rear of Charlecott Close Moseley Birmingham B13 0DE Erection of a two storey residential building consisting of four flats with associated landscaping and parking Approve-Conditions 12 2018/07187/PA Weoley Avenue Lodge Hill Cemetery Lodge Hill Birmingham B29 6PS Land re-profiling works construction of a attenuation/ detention basin Approve-Conditions 13 2018/06094/PA 4 Waldrons Moor Kings Heath Birmingham B14 6RS Erection of two storey side and single storey front, side and rear extensions. -

Flood Risk Management Annual Report – March 2019

Birmingham City Council Flood Risk Management Annual Report – March 2019 Flood Risk Management Annual Report Report of the Assistant Director Highways and Infrastructure - March 2019 1. Introduction A scrutiny review of Flood Risk Management and Response was published in June 2010. This set out 12 recommendations which were completed in 2010. In June 2010, The Flood and Water Management Act 2010 passed into law conveying new responsibilities and making Birmingham City Council a Lead Local Flood Authority (LLFA). This report highlights progress in addressing these statutory responsibilities and provides an update on other flood risk management related issues. This report also provides an update into areas for improvement identified in the review of the May 2018 flooding conducted by members of the Sustainability & Transport O&S Committee on 19th July 2018. 2. Flood and Water Management Act Duties The following work has been undertaken to fulfil the LLFA duties under the Flood and Water Management Act. 2.1 Local Flood Risk Management Strategy The Local Flood Risk Management Strategy for Birmingham, October 2017 continues set out the objectives for managing local flood risk and the measures proposed to achieve those objectives. 2.2 Cooperation with other Flood Risk Management Authorities The LLFA continues to cooperate extensively with other risk management authorities (RMAs) at various levels as established in the 3 tiered flood risk management governance structure. 2.2.1 Strategic Flood Risk Management Board The Strategic Board last met in December 2017 and due to the loss of a number of Flood Risk Management staff it was not possible to convene a meeting during 2018. -

C Re Strategy 2026 a Plan for Sustainable Growth

INTRODUCTION • CORE STRATEGY Birmingham c re strategy 2026 A plan for sustainable growth Consultation Draft • December 2010 theBirminghamplan birmingham’s local development framework Birmingham c re strategy 2026 A plan for sustainable growth Consultation Draft • December 2010 Closing date for comments 18th March 2011. Contact: Planning Strategy PO Box 14439 1 Lancaster Circus Birmingham B2 2JE E-mail: [email protected] Telephone: (0121) 303 3734 Mark Barrow Strategic Director of Development theBirminghamplan birmingham’s local development framework Foreword I am very pleased to be endorsing this emerging Core Strategy. It will play a key role in helping to shape the future direction of this great city. Birmingham is a diverse, dynamic and forward thinking city of over a million people. It is the regional capital of the Midlands and is strategically located at the heart of the United Kingdom. The city has seen constant and progressive change throughout its history, embracing new cultures and the challenges of shifting global economies and more recently climate change. Over recent years there has been a transformation of the city centre, including the rebuilding of the Bullring, development of concert/ conferencing and sporting facilities and the creation of attractive public squares and spaces all to the highest international standards. The city will continue to adapt to and embrace change, in order to enhance its position as a key economic and cultural centre regionally, nationally and internationally. Further expansion will see development of a state of the art ‘Library for Birmingham’ the new central library, the redevelopment of New Street railway station and expansion of Birmingham International Airport. -

Birmingham School Games 2020-21

Secondary – 17th May – 24th May 2021 How to Use this Resource Over the course of the summer term, Birmingham SGO’s will be running 4 themed weeks to support your school and young people. We encourage you to use the resources and activities in the best way for your school – feel free to share with colleagues, parents and carers and young people! If your school has social media or internal school platforms, please feel free to share the Birmingham School Games message! www.sgochallenge.com #backtoschoolgames Secondary Challenge 1 Photograph Challenge For this challenge, we would like you to capture the best of the city of Birmingham. Categories: - Architecture (bridges, buildings, statues etc.) - Flora(trees, flowers etc.) - Fauna (animals, insects, birds etc.) - Landscapes - Sporting theme Photographic Tips You do not need any special or fancy camera, you can use your mobile phone. Your photographs might be used to promote School Games activities, used on social media, in printed documents or other Try lots of different angles when taking images and then select your favourite. media. Please ensure you are happy for your photographs to be used in this way before you submit them. Be creative – take photographs when you are on a family walk, cycle, scooters, skateboard, wheelchair or when you are travelling to school or on a shopping trip. www.sgochallenge.com #backtoschoolgames Birmingham Architecture Flora (Trees, flowers and plants) Fauna (Animals, insects, birds) Go out into your local parks or nearest recreation areas where you live with your camera or mobile phone. Cycle/scooter/skateboard ride or wheelchair in your local area or local woodland area e.g.