The Structure of Scientific Revolutions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Louis Rougier : Vie Et Œuvre D'un Philosophe Engagé

Philosophia Scientiæ Travaux d'histoire et de philosophie des sciences CS 7 | 2007 Louis Rougier : vie et œuvre d'un philosophe engagé Louis Rougier : itinéraire intellectuel et politique, des années vingt à Nouvelle École Olivier Dard Édition électronique URL : http://journals.openedition.org/philosophiascientiae/429 DOI : 10.4000/philosophiascientiae.429 ISSN : 1775-4283 Éditeur Éditions Kimé Édition imprimée Date de publication : 1 janvier 2007 Pagination : 50-64 ISBN : 978-2-84174-412-1 ISSN : 1281-2463 Référence électronique Olivier Dard, « Louis Rougier : itinéraire intellectuel et politique, des années vingt à Nouvelle École », Philosophia Scientiæ [En ligne], CS 7 | 2007, mis en ligne le 08 juin 2011, consulté le 15 janvier 2021. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/philosophiascientiae/429 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/ philosophiascientiae.429 Tous droits réservés Louis Rougier : itinéraire intellectuel et politique, des années vingt à Nouvelle École Olivier Dard CRULH - Université Paul Verlaine - Metz Depuis sa mort, Louis Rougier (1889-1982) est largement oublié par le débat public et l’historiographie. Les libéraux en particulier, dont Rou- gier fut un des hérauts ne se sont guère réclamés de son héritage, à l’exception de Maurice Allais [Allais 1990]. La dimension sulfureuse at- tachée au personnage et liée à ses sympathies vichyssoises (qu’il faut remettre en perspective) comme à sa proximité avec la Nouvelle droite1 n’ont sans doute rien arrangé. C’est quoi qu’il en soit Alain de Benoist, fondateur et principal animateur de la Nouvelle droite et qui fut à la fois un intime et un disciple philosophique de Rougier au début des années 60 qui a perpétué le plus fidèlement son héritage en rééditant certains de ses livres avec des préfaces substantielles.2 Du côté de l’historiogra- phie, l’éclairage sur Rougier se limite à deux épisodes principaux : sa participation au néo-libéralisme de l’entre-deux-guerres et au colloque Philosophia Scientiæ, Cahier spécial 7, 2007, 50–64. -

The Philosophy of Physics

The Philosophy of Physics ROBERTO TORRETTI University of Chile PUBLISHED BY THE PRESS SYNDICATE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CAMBRIDGE The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge, United Kingdom CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge CB2 2RU, UK www.cup.cam.ac.uk 40 West 20th Street, New York, NY 10011-4211, USA www.cup.org 10 Stamford Road, Oakleigh, Melbourne 3166, Australia Ruiz de Alarcón 13, 28014, Madrid, Spain © Roberto Torretti 1999 This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published 1999 Printed in the United States of America Typeface Sabon 10.25/13 pt. System QuarkXPress [BTS] A catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available. 0 521 56259 7 hardback 0 521 56571 5 paperback Contents Preface xiii 1 The Transformation of Natural Philosophy in the Seventeenth Century 1 1.1 Mathematics and Experiment 2 1.2 Aristotelian Principles 8 1.3 Modern Matter 13 1.4 Galileo on Motion 20 1.5 Modeling and Measuring 30 1.5.1 Huygens and the Laws of Collision 30 1.5.2 Leibniz and the Conservation of “Force” 33 1.5.3 Rømer and the Speed of Light 36 2 Newton 41 2.1 Mass and Force 42 2.2 Space and Time 50 2.3 Universal Gravitation 57 2.4 Rules of Philosophy 69 2.5 Newtonian Science 75 2.5.1 The Cause of Gravity 75 2.5.2 Central Forces 80 2.5.3 Analytical -

Michael Polanyi and Early Neoliberalism

MICHAEL POLANYI AND EARLY NEOLIBERALISM Martin Beddeleem Keywords: Friedrich Hayek, Louis Rougier, Michael Polanyi, Mont-Pèlerin Society, neoliberalism, planning, Walter Lippmann ABSTRACT1 Between the late 1930s and the 1950s, Michael Polanyi came in close contact with a diverse cast of intellectuals seeking a renewal of the liberal doctrine. The elaboration of this “neoliberalism” happened through a transnational collaboration between economists, philosophers, and social theorists, united in their rejection of central planning. Defining a common agenda for this “early neoliberalism” offered an opportunity to discard the old laissez-faire doctrine and restore a supervisory role of the state. Ultimately, post-war dissensions regarding the direction of these efforts led Polanyi away from the neoliberal core. Between the publication of his pamphlet on the failures of economic planning in the Soviet Union in 1936 (CF, 61-95) and that of The Logic of Liberty in 1951, Michael Polanyi progressively lost interest in chemistry and started to investigate the political and sociological conditions necessary to scientific freedom and the pursuit of truth. During that time, he became involved with a group of scholars who, equally, perceived the democratic collapse of Europe as a wake-up call for a restatement of its liberal tradition. Whereas the values of individual dignity and social progress that liber- alism carried were needed then more than ever, they agreed that the method to achieve these ideals had become obsolete. Therefore, they focused their efforts on revamping a science of liberalism, which could answer the scientific claims of plannism and totalitar- ian ideologies. Tradition & Discovery: The Journal of the Polanyi Society 45:3 © 2019 by the Polanyi Society 31 For two decades, Michael Polanyi took part in the inception and the consolida- tion of “early neoliberalism” (Schulz-Forberg 2018; Beddeleem 2019), a period that predates the later development of neoliberalism from the 1960s onwards. -

Couch's “Physical Alteration” Fallacy: Its Origins And

COUCH’S “PHYSICAL ALTERATION” FALLACY: ITS ORIGINS AND CONSEQUENCES Richard P. Lewis,∗ Lorelie S. Masters,∗∗ Scott D. Greenspan*** & Chris Kozak∗∗∗∗ I. INTRODUCTION Look at virtually any Covid-19 case favoring an insurer, and you will find a citation to Section 148:46 of Couch on Insurance.1 It is virtually ubiquitous: courts siding with insurers cite Couch as restating a “widely held rule” on the meaning of “physical loss or damage”—words typically in the trigger for property-insurance coverage, including business- income coverage. It has been cited, ad nauseam, as evidence of a general consensus that all property-insurance claims require some “distinct, demonstrable, physical alteration of the property.”2 Indeed, some pro-insurer decisions substitute a citation to this section for an actual analysis of the specific language before the court. Couch is generally recognized as a significant insurance treatise, and courts have cited it for almost a century.3 That ∗ Partner, ReedSmith LLP, New York. ∗∗ Partner, Hunton Andrews Kurth LLP, Washington D.C. *** Senior Counsel, Pillsbury Winthrop Shaw Pittman LLP, New York. ∗∗∗∗ Associate, Plews Shadley Racher & Braun, LLP, Indianapolis. 1 10A STEVEN PLITT, ET AL., COUCH ON INSURANCE 3D § 148:46. As shown below, some courts quote Couch itself, while others cite cases citing Couch and merely intone the “distinct, demonstrable, physical alteration” language without citing Couch itself. Couch First and Couch Second were published in hardback books (with pocket parts), in 1929 and 1959 respectively. As explained below (infra n.5), Couch 3d, a looseleaf, was first published in 1995.. 2 Id. (emphasis added); Oral Surgeons, P.C. -

Newton.Indd | Sander Pinkse Boekproductie | 16-11-12 / 14:45 | Pag

omslag Newton.indd | Sander Pinkse Boekproductie | 16-11-12 / 14:45 | Pag. 1 e Dutch Republic proved ‘A new light on several to be extremely receptive to major gures involved in the groundbreaking ideas of Newton Isaac Newton (–). the reception of Newton’s Dutch scholars such as Willem work.’ and the Netherlands Jacob ’s Gravesande and Petrus Prof. Bert Theunissen, Newton the Netherlands and van Musschenbroek played a Utrecht University crucial role in the adaption and How Isaac Newton was Fashioned dissemination of Newton’s work, ‘is book provides an in the Dutch Republic not only in the Netherlands important contribution to but also in the rest of Europe. EDITED BY ERIC JORINK In the course of the eighteenth the study of the European AND AD MAAS century, Newton’s ideas (in Enlightenment with new dierent guises and interpre- insights in the circulation tations) became a veritable hype in Dutch society. In Newton of knowledge.’ and the Netherlands Newton’s Prof. Frans van Lunteren, sudden success is analyzed in Leiden University great depth and put into a new perspective. Ad Maas is curator at the Museum Boerhaave, Leiden, the Netherlands. Eric Jorink is researcher at the Huygens Institute for Netherlands History (Royal Dutch Academy of Arts and Sciences). / www.lup.nl LUP Newton and the Netherlands.indd | Sander Pinkse Boekproductie | 16-11-12 / 16:47 | Pag. 1 Newton and the Netherlands Newton and the Netherlands.indd | Sander Pinkse Boekproductie | 16-11-12 / 16:47 | Pag. 2 Newton and the Netherlands.indd | Sander Pinkse Boekproductie | 16-11-12 / 16:47 | Pag. -

Philipp Frank at Harvard University: His Work and His Influence

Philipp Frank at Harvard University: His Work and His Influence The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Holton, Gerald. 2006. Phillip Frank at Harvard: His Work and his Influence. Synthese 153 (2): 297-311. doi.org/10.1007/ s11229-005-5471-3 Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:37837879 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA 10/12/04 Lecture at Philipp Frank Conferences in Prague & Vienna, Sept-Oct. ‘04 Philipp Frank at Harvard: His Work and his Influence by Gerald Holton My pleasant task today is to bring to life Philipp Frank’s work and influence during his last three decades, when he found a refuge and a position in America. In what follows, I hope I may call him Philipp--having been first a graduate student in one of his courses at Harvard, then his teaching assistant sharing his offices, then for many years his colleague and friend in the same Physics Department, and finally, doing research on his archival holdings kept at Harvard. I also should not hide my large personal debt to him, for without his recommendation in the 1950s to the Albert Einstein Estate, I would not have received its warm welcome and its permission, as the first one to do historical research in the treasure trove of unpublished letters and manuscripts, thus starting me on a major part of my career in the history of science. -

Sacred Rhetorical Invention in the String Theory Movement

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Communication Studies Theses, Dissertations, and Student Research Communication Studies, Department of Spring 4-12-2011 Secular Salvation: Sacred Rhetorical Invention in the String Theory Movement Brent Yergensen University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/commstuddiss Part of the Speech and Rhetorical Studies Commons Yergensen, Brent, "Secular Salvation: Sacred Rhetorical Invention in the String Theory Movement" (2011). Communication Studies Theses, Dissertations, and Student Research. 6. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/commstuddiss/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Communication Studies, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Communication Studies Theses, Dissertations, and Student Research by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. SECULAR SALVATION: SACRED RHETORICAL INVENTION IN THE STRING THEORY MOVEMENT by Brent Yergensen A DISSERTATION Presented to the Faculty of The Graduate College at the University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Major: Communication Studies Under the Supervision of Dr. Ronald Lee Lincoln, Nebraska April, 2011 ii SECULAR SALVATION: SACRED RHETORICAL INVENTION IN THE STRING THEORY MOVEMENT Brent Yergensen, Ph.D. University of Nebraska, 2011 Advisor: Ronald Lee String theory is argued by its proponents to be the Theory of Everything. It achieves this status in physics because it provides unification for contradictory laws of physics, namely quantum mechanics and general relativity. While based on advanced theoretical mathematics, its public discourse is growing in prevalence and its rhetorical power is leading to a scientific revolution, even among the public. -

Natural Science 1

Natural Science 1 Required Courses NATURAL SCIENCE Select 18 units from the following: 18 AGRI 0198 Food, Society and the Environment Contact Information AGRI 0221 Introduction to Soil Science ANTH 0001 Physical Anthropology Division ANTH 0001L Physical Anthropology Laboratory Sciences and Mathematics ANTH 0010 Introduction to Forensic Anthropology Dean ASTR 0002 Introduction to Planetary Systems Heather Roberts ASTR 0005 Introduction to Stars, Galaxies, and the Associate Dean Universe Karen Warburton ASTR 0007 Life in the Universe Division Office ASTR 0010 Elementary Astronomy V 211, Rocklin Campus ASTR 0011 Observational Astronomy ASTR 0014 Astrophotography and Imaging Overview ASTR 0025 Frontiers in Astronomy Courses from the following departments are included in the BIOL 0001 General Biology interdisciplinary Natural Science associate degree: BIOL 0002 Botany BIOL 0003 General Zoology • Agriculture BIOL 0004 Microbiology • Anthropology BIOL 0005 Human Anatomy • Astronomy BIOL 0006 Human Physiology • Biological Sciences BIOL 0007A Human Anatomy I • Chemistry BIOL 0007B Human Anatomy II • Earth Science BIOL 0008A Microbiology I • Environmental Studies and Sustainability BIOL 0008B Microbiology II • Geography BIOL 0010 Introduction to Biology • Mathematics BIOL 0011 Concepts of Biology • Physics BIOL 0014 Natural History, Ecology and • Psychology Conservation (also ESS 0014) BIOL 0015 Marine Biology Degrees/Certificates BIOL 0021 Introduction to Plant Science (also Natural Science AGRI 0156) AA or AS Degree BIOL 0024 Wildland Trees and Shrubs The Natural Science degree is designed for students who are pursuing (Dendrology) transfer majors in the Natural Sciences, including Astronomy, Biological BIOL 0033 Introduction to Zoology Science, Chemistry, Geography, Geology, Physics and related disciplines. BIOL 0055 General Human Anatomy and In all cases, students should consult with a counselor for more Physiology information on university admission and transfer requirements. -

Newton's Mathematical Physics

Isaac Newton A new era in science Waseda University, SILS, Introduction to History and Philosophy of Science LE201, History and Philosophy of Science Newton . Newton’s Legacy Newton brought to a close the astronomical revolution begun by Copernicus. He combined the dynamic research of Galileo with the astronomical work of Kepler. He produced an entirely new cosmology and a new way of thinking about the world, based on the interaction between matter and mathematically determinate forces. He joined the mathematical and experimental methods: the hypothetico-deductive method. His work became the model for rational mechanics as it was later practiced by mathematicians, particularly during the Enlightenment. LE201, History and Philosophy of Science Newton . William Blake’s Newton (1795) LE201, History and Philosophy of Science Newton LE201, History and Philosophy of Science Newton . Newton’s De Motu coporum in gyrum Edmond Halley (of the comet) visited Cambridge in 1684 and 1 talked with Newton about inverse-square forces (F 9 d2 ). Newton stated that he has already shown that inverse-square force implied an ellipse, but could not find the documents. Later he rewrote this into a short document called De Motu coporum in gyrum, and sent it to Halley. Halley was excited and asked for a full treatment of the subject. Two years later Newton sent Book I of The Mathematical Principals of Natural Philosophy (Principia). Key Point The goal of this project was to derive the orbits of bodies from a simpler set of assumptions about motion. That is, it sought to explain Kepler’s Laws with a simpler set of laws. -

Dossier Pierre Duhem Pierre Duhem's Philosophy and History of Science

Transversal: International Journal for the Historiography of Science , 2 (201 7) 03 -06 ISSN 2526 -2270 www.historiographyofscience.org © The Author s 201 7 — This is an open access article Dossier Pierre Duhem Pierre Duhem’s Philos ophy and History of Science Introduction Fábio Rodrigo Leite 1 Jean-François Stoffel 2 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.24117/2526-2270.2017.i2.02 _____________________________________________________________________________ We are pleased to present in this issue a tribute to the thought of Pierre Duhem, on the occasion of the centenary of his death that occurred in 2016. Among articles and book reviews, the dossier contains 14 contributions of scholars from different places across the world, from Europe (Belgium, Greece, Italy, Portugal and Sweden) to the Americas (Brazil, Canada, Mexico and the United States). And this is something that attests to the increasing scope of influence exerted by the French physicist, philosopher and 3 historian. It is quite true that since his passing, Duhem has been remembered in the writings of many of those who knew him directly. However, with very few exceptions (Manville et al. 1927), the comments devoted to him exhibited clear biographical and hagiographic characteristics of a generalist nature (see Jordan 1917; Picard 1921; Mentré 1922a; 1922b; Humbert 1932; Pierre-Duhem 1936; Ocagne et al. 1937). From the 1950s onwards, when the studies on his philosophical work resumed, the thought of the Professor from Bordeaux acquired an irrevocable importance, so that references to La théorie physique: Son objet et sa structure became a common place in the literature of the area. As we know, this recovery was a consequence of the prominence attributed, firstly, to the notorious Duhem-Quine thesis in the English- speaking world, and secondly to the sparse and biased comments made by Popper that generated an avalanche of revaluations of the Popperian “instrumentalist interpretation”. -

6 X 10.5 Long Title.P65

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-80279-6 - God and Reason in the Middle Ages Edward Grant Index More information INDEX Page numbers cited directly after a semicolon following a final text subentry refer to relatively minor mentions in the text of the main entry. Abelard, Peter: application of logic to theology, Questions on Generation and Corruption, 186; 57–9; importance of, 48; opposed reason to Questions on the Physics, 186, 187, 190–1; 153, authority, 357; Sic et Non, 60, 62, 79; 26, 46, 170, 275nn, 276nn 50, 51, 62, 63, 64, 73, 100, 144, 333, 337 Albertus Magnus: and the senses, 160; as accidents: lacking a subject, 252; 183 theologian-natural philosopher, 191; few acoustics, 163 mentions of God, 194–5; on God’s absolute Adalberon of Laon, 47 power, 193; on other worlds, 193; on relations Adelard of Bath: as translator, 69; attitude toward between natural philosophy and theology, authority and reason, 69–72; natural 192–5; Commentary on De caelo, 192, 193, 194; philosophy of, 69–72; opposed reason to Commentary on the Physics, 192, 194; 104, 161, authority, 357; Natural Questions, 69, 84; 73, 74 179, 180, 196, 344 Age of Enlightenment: based on seventeenth- Albigenses, 336 century thought, 284 Albucasis, 109 Age of Faith: rather than Age of Reason, 351; 335 Alexander of Aphrodisias, 86 Age of Reason: and Middle Ages, 15, 16, 285; Alexander of Hales, 207, 254nn arrived at religion based on reason, 289; al-Farghani, see Alfraganus began in Middle Ages, 8–9, 289, 290; could Alfraganus, 341 not have occurred without Middle Ages, 292; -

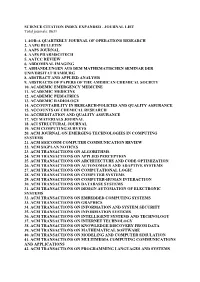

SCIENCE CITATION INDEX EXPANDED - JOURNAL LIST Total Journals: 8631

SCIENCE CITATION INDEX EXPANDED - JOURNAL LIST Total journals: 8631 1. 4OR-A QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF OPERATIONS RESEARCH 2. AAPG BULLETIN 3. AAPS JOURNAL 4. AAPS PHARMSCITECH 5. AATCC REVIEW 6. ABDOMINAL IMAGING 7. ABHANDLUNGEN AUS DEM MATHEMATISCHEN SEMINAR DER UNIVERSITAT HAMBURG 8. ABSTRACT AND APPLIED ANALYSIS 9. ABSTRACTS OF PAPERS OF THE AMERICAN CHEMICAL SOCIETY 10. ACADEMIC EMERGENCY MEDICINE 11. ACADEMIC MEDICINE 12. ACADEMIC PEDIATRICS 13. ACADEMIC RADIOLOGY 14. ACCOUNTABILITY IN RESEARCH-POLICIES AND QUALITY ASSURANCE 15. ACCOUNTS OF CHEMICAL RESEARCH 16. ACCREDITATION AND QUALITY ASSURANCE 17. ACI MATERIALS JOURNAL 18. ACI STRUCTURAL JOURNAL 19. ACM COMPUTING SURVEYS 20. ACM JOURNAL ON EMERGING TECHNOLOGIES IN COMPUTING SYSTEMS 21. ACM SIGCOMM COMPUTER COMMUNICATION REVIEW 22. ACM SIGPLAN NOTICES 23. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON ALGORITHMS 24. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON APPLIED PERCEPTION 25. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON ARCHITECTURE AND CODE OPTIMIZATION 26. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON AUTONOMOUS AND ADAPTIVE SYSTEMS 27. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON COMPUTATIONAL LOGIC 28. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON COMPUTER SYSTEMS 29. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON COMPUTER-HUMAN INTERACTION 30. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON DATABASE SYSTEMS 31. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON DESIGN AUTOMATION OF ELECTRONIC SYSTEMS 32. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON EMBEDDED COMPUTING SYSTEMS 33. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON GRAPHICS 34. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON INFORMATION AND SYSTEM SECURITY 35. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON INFORMATION SYSTEMS 36. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON INTELLIGENT SYSTEMS AND TECHNOLOGY 37. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON INTERNET TECHNOLOGY 38. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON KNOWLEDGE DISCOVERY FROM DATA 39. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON MATHEMATICAL SOFTWARE 40. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON MODELING AND COMPUTER SIMULATION 41. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON MULTIMEDIA COMPUTING COMMUNICATIONS AND APPLICATIONS 42. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON PROGRAMMING LANGUAGES AND SYSTEMS 43. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON RECONFIGURABLE TECHNOLOGY AND SYSTEMS 44.