Peep Identification

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Common Caribbean Shorebirds: ID Guide

Common Caribbean Shorebirds: ID Guide Large Medium Small 14”-18” 35 - 46 cm 8.5”-12” 22 - 31 cm 6”- 8” 15 - 20 cm Large Shorebirds Medium Shorebirds Small Shorebirds Whimbrel 17.5” 44.5 cm Lesser Yellowlegs 9.5” 24 cm Wilson’s Plover 7.75” 19.5 cm Spotted Sandpiper 7.5” 19 cm American Oystercatcher 17.5” 44.5 cm Black-bellied Plover 11.5” 29 cm Sanderling 7.75” 19.5 cm Western Sandpiper 6.5” 16.5 cm Willet 15” 38 cm Short-billed Dowitcher 11” 28 cm White-rumped Sandpiper 6” 15 cm Greater Yellowlegs 14” 35.5 cm Ruddy Turnstone 9.5” 24 cm Semipalmated Sandpiper 6.25” 16 cm 6.25” 16 cm American Avocet* 18” 46 cm Red Knot 10.5” 26.5 cm Snowy Plover Least Sandpiper 6” 15 cm 14” 35.5 cm 8.5” 21.5 cm Semipalmated Plover Black-necked Stilt* Pectoral Sandpiper 7.25” 18.5 cm Killdeer* 10.5” 26.5 cm Piping Plover 7.25” 18.5 cm Stilt Sandpiper* 8.5” 21.5 cm Lesser Yellowlegs & Ruddy Turnstone: Brad Winn; Red Knot: Anthony Levesque; Pectoral Sandpiper & *not pictured Solitary Sandpiper* 8.5” 21.5 cm White-rumped Sandpiper: Nick Dorian; All other photos: Walker Golder Clues to help identify shorebirds Size & Shape Bill Length & Shape Foraging Behavior Size Length Sandpipers How big is it compared to other birds? Peeps (Semipalmated, Western, Least) Walk or run with the head down, picking and probing Spotted Sandpiper Short Medium As long Longer as head than head Bobs tail up and down when walking Plovers, Turnstone or standing Small Medium Large Sandpipers White-rumped Sandpiper Tail tips up while probing Yellowlegs Overall Body Shape Stilt Sandpiper Whimbrel, Oystercatcher, Probes mud like “oil derrick,” Willet, rear end tips up Dowitcher, Curvature Plovers Stilt, Avocet Run & stop, pick, hiccup, run & stop Elongate Compact Yellowlegs Specific Body Parts Stroll and pick Bill & leg color Straight Upturned Dowitchers Eye size Plovers = larger, sandpipers = smaller Tip slightly Probe mud with “sewing machine” Leg & neck length downcurved Downcurved bill, body stays horizontal . -

Draft Version Target Shorebird Species List

Draft Version Target Shorebird Species List The target species list (species to be surveyed) should not change over the course of the study, therefore determining the target species list is an important project design task. Because waterbirds, including shorebirds, can occur in very high numbers in a census area, it is often not possible to count all species without compromising the quality of the survey data. For the basic shorebird census program (protocol 1), we recommend counting all shorebirds (sub-Order Charadrii), all raptors (hawks, falcons, owls, etc.), Common Ravens, and American Crows. This list of species is available on our field data forms, which can be downloaded from this site, and as a drop-down list on our online data entry form. If a very rare species occurs on a shorebird area survey, the species will need to be submitted with good documentation as a narrative note with the survey data. Project goals that could preclude counting all species include surveys designed to search for color-marked birds or post- breeding season counts of age-classed bird to obtain age ratios for a species. When conducting a census, you should identify as many of the shorebirds as possible to species; sometimes, however, this is not possible. For example, dowitchers often cannot be separated under censuses conditions, and at a distance or under poor lighting, it may not be possible to distinguish some species such as small Calidris sandpipers. We have provided codes for species combinations that commonly are reported on censuses. Combined codes are still species-specific and you should use the code that provides as much information as possible about the potential species combination you designate. -

Purple Sandpiper

Maine 2015 Wildlife Action Plan Revision Report Date: January 13, 2016 Calidris maritima (Purple Sandpiper) Priority 1 Species of Greatest Conservation Need (SGCN) Class: Aves (Birds) Order: Charadriiformes (Plovers, Sandpipers, And Allies) Family: Scolopacidae (Curlews, Dowitchers, Godwits, Knots, Phalaropes, Sandpipers, Snipe, Yellowlegs, And Woodcock) General comments: Recent surveys suggest population undergoing steep population decline within 10 years. IFW surveys conducted in 2014 suggest population declined by 49% since 2004 (IFW unpublished data). Maine has high responsibility for wintering population, regional surveys suggest Maine may support over 1/3 of the Western Atlantic wintering population. USFWS Region 5 and Canadian Maritimes winter at least 90% of the Western Atlantic population. Species Conservation Range Maps for Purple Sandpiper: Town Map: Calidris maritima_Towns.pdf Subwatershed Map: Calidris maritima_HUC12.pdf SGCN Priority Ranking - Designation Criteria: Risk of Extirpation: NA State Special Concern or NMFS Species of Concern: NA Recent Significant Declines: Purple Sandpiper is currently undergoing steep population declines, which has already led to, or if unchecked is likely to lead to, local extinction and/or range contraction. Notes: Recent surveys suggest population undergoing steep population decline within 10 years. IFW surveys conducted in 2014 suggest population declined by 49% since 2004 (IFW unpublished data). Maine has high responsibility for wintering populat Regional Endemic: Calidris maritima's global geographic range is at least 90% contained within the area defined by USFWS Region 5, the Canadian Maritime Provinces, and southeastern Quebec (south of the St. Lawrence River). Notes: Recent surveys suggest population undergoing steep population decline within 10 years. IFW surveys conducted in 2014 suggest population declined by 49% since 2004 (IFW unpublished data). -

Biogeographical Profiles of Shorebird Migration in Midcontinental North America

U.S. Geological Survey Biological Resources Division Technical Report Series Information and Biological Science Reports ISSN 1081-292X Technology Reports ISSN 1081-2911 Papers published in this series record the significant find These reports are intended for the publication of book ings resulting from USGS/BRD-sponsored and cospon length-monographs; synthesis documents; compilations sored research programs. They may include extensive data of conference and workshop papers; important planning or theoretical analyses. These papers are the in-house coun and reference materials such as strategic plans, standard terpart to peer-reviewed journal articles, but with less strin operating procedures, protocols, handbooks, and manu gent restrictions on length, tables, or raw data, for example. als; and data compilations such as tables and bibliogra We encourage authors to publish their fmdings in the most phies. Papers in this series are held to the same peer-review appropriate journal possible. However, the Biological Sci and high quality standards as their journal counterparts. ence Reports represent an outlet in which BRD authors may publish papers that are difficult to publish elsewhere due to the formatting and length restrictions of journals. At the same time, papers in this series are held to the same peer-review and high quality standards as their journal counterparts. To purchase this report, contact the National Technical Information Service, 5285 Port Royal Road, Springfield, VA 22161 (call toll free 1-800-553-684 7), or the Defense Technical Infonnation Center, 8725 Kingman Rd., Suite 0944, Fort Belvoir, VA 22060-6218. Biogeographical files o Shorebird Migration · Midcontinental Biological Science USGS/BRD/BSR--2000-0003 December 1 By Susan K. -

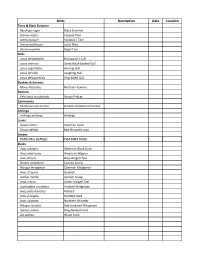

Bird Species Check List

Birds Description Date Location Terns & Black Skimmer Rynchops niger Black Skimmer Sterna caspia Caspian Tern Stema forsteri Forester's Tern Sterna antillarum Least Tern Sterna maxima Royal Tern Gulls Larus philadelphia Bonaparte's Gull Larus marinus Great Black‐backed Gull Larus argentatus Herring Gull Larus atricilla Laughing Gull Larus delawarensis Ring‐billed Gull Boobies & Gannets Morus bassanus Northern Gannet Pelicans Pelecanus occidentalis Brown Pelican Cormorants Phalacrocorax auritus Double‐Crested Cormorant Anhinga Anhinga anhinga Anhinga Loons Gavia immer Common Loon Gavia stellata Red‐throated Loon Grebes PodilymbusPodil ymbus popodicepsdiceps PiPieded‐billbilleded GrebeGrebe Ducks Anas rubripes American Black Duck Anas americana American Wigeon Anas discors Blue‐winged Teal Branta canadensis Canada Goose Mergus merganser Common Merganser Anas strepera Gadwall Aythya marila Greater Scaup Anas crecca Green‐winged Teal Lophodytes cucullatus Hooded Merganser Anas platyrhynchos Mallard Anas fulvigula Mottled Duck Anas clypeata Northern Shoveler Mergus serrator Red‐breasted Merganser Aythya collaris Ring‐Necked Duck Aix sponsa Wood Duck Birds Description Date Location Rails & Northern Jacana Fulica americana American Coot Rallus longirostris Clapper Rail Gallinula chloropus Common Moorhen Rallus elegans King Rail Porzana carolina Sora Long‐legged Waders Nycticorax nycticorax Black‐crowned Night‐Heron Bubulcus ibis Cattle Egret Plegadis falcinellus Glossy Ibis Ardea herodias Great Blue Heron Casmerodius albus Great Egret Butorides -

List of Shorebird Profiles

List of Shorebird Profiles Pacific Central Atlantic Species Page Flyway Flyway Flyway American Oystercatcher (Haematopus palliatus) •513 American Avocet (Recurvirostra americana) •••499 Black-bellied Plover (Pluvialis squatarola) •488 Black-necked Stilt (Himantopus mexicanus) •••501 Black Oystercatcher (Haematopus bachmani)•490 Buff-breasted Sandpiper (Tryngites subruficollis) •511 Dowitcher (Limnodromus spp.)•••485 Dunlin (Calidris alpina)•••483 Hudsonian Godwit (Limosa haemestica)••475 Killdeer (Charadrius vociferus)•••492 Long-billed Curlew (Numenius americanus) ••503 Marbled Godwit (Limosa fedoa)••505 Pacific Golden-Plover (Pluvialis fulva) •497 Red Knot (Calidris canutus rufa)••473 Ruddy Turnstone (Arenaria interpres)•••479 Sanderling (Calidris alba)•••477 Snowy Plover (Charadrius alexandrinus)••494 Spotted Sandpiper (Actitis macularia)•••507 Upland Sandpiper (Bartramia longicauda)•509 Western Sandpiper (Calidris mauri) •••481 Wilson’s Phalarope (Phalaropus tricolor) ••515 All illustrations in these profiles are copyrighted © George C. West, and used with permission. To view his work go to http://www.birchwoodstudio.com. S H O R E B I R D S M 472 I Explore the World with Shorebirds! S A T R ER G S RO CHOOLS P Red Knot (Calidris canutus) Description The Red Knot is a chunky, medium sized shorebird that measures about 10 inches from bill to tail. When in its breeding plumage, the edges of its head and the underside of its neck and belly are orangish. The bird’s upper body is streaked a dark brown. It has a brownish gray tail and yellow green legs and feet. In the winter, the Red Knot carries a plain, grayish plumage that has very few distinctive features. Call Its call is a low, two-note whistle that sometimes includes a churring “knot” sound that is what inspired its name. -

Ageing and Sexing the Common Sandpiper Actitis Hypoleucos

ageing & sexing series Wader Study 122(1): 54 –59. 10.18194/ws.00009 This series summarizing current knowledge on ageing and sexing waders is co-ordinated by Włodzimier Meissner (Avian Ecophysiology Unit, Department of Vertebrate Ecology & Zoology, University of Gdansk, ul. Wita Stwosza 59, 80-308 Gdansk, Poland, [email protected]). See Wader Study Group Bulletin vol. 113 p. 28 for the Introduction to the series. Part 11: Ageing and sexing the Common Sandpiper Actitis hypoleucos Włodzimierz Meissner 1, Philip K. Holland 2 & Tomasz Cofta 3 1Avian Ecophysiology Unit, Department of Vertebrate Ecology & Zoology, University of Gdańsk, ul.Wita Stwosza 59, 80-308 Gdańsk, Poland. [email protected] 232 Southlands, East Grinstead, RH19 4BZ, UK. [email protected] 3Hoene 5A/5, 80-041 Gdańsk, Poland. [email protected] Meissner, W., P.K. Holland & T. Coa. 2015. Ageing and sexing series 11: Ageing and sexing the Common Sandpiper Actitis hypoleucos . Wader Study 122(1): 54 –59. Keywords: Common Sandpiper, Actitis hypoleucos , ageing, sexing, moult, plumages The Common Sandpiper Actitis hypoleucos is treated as were validated using about 500 photographs available on monotypic through a breeding range that extends from the Internet and about 50 from WRG KULING ringing Ireland eastwards to Japan. Its main non-breeding area is sites in northern Poland. also vast, reaching from the Canary Islands to Australia with a few also in the British Isles, France, Spain, Portugal MOULT SCHEDULE and the Mediterranean (Cramp & Simmons 1983, del Juveniles and adults leave the breeding grounds as soon Hoyo et al. 1996, Glutz von Blotzheim et al. -

First Record of the Terek Sandpiper in California

FIRST RECORD OF THE TEREK SANDPIPER IN CALIFORNIA ERIKA M. WILSON, 1400 S. BartonSt. #421, Arlington,Virginia 22204 BETTIE R. HARRIMAN, 5188 BittersweetLane, Oshkosh,Wisconsin 54901 On 28 August 1988, while birding at Carmel River State Beach, MontereyCounty, California(36032 ' N, 121057' W), we discoveredan adult Terek Sandpiper (Xenus cinereus). We watched this Eurasian vagrantbetween 1110 and 1135 PDT; we saw it again,along with local birders, between 1215 and 1240 as it foraged on the open beach. Wilson observedthe bird a third time on 5 September 1988 between 1000 and 1130; otherssaw it regularlyuntil 23 September1988. During our first observationa light overcastsky resultedin good viewingconditions, without glare or strongshadows. The weather was mild with a slightbreeze and some offshorefog. We found the Terek Sandpiperfeeding in the Carmel River'sshallow lagoon, separated from the Pacific Ocean by sand dunes. Its long, upturnedbill, quite out of keepingwith any smallwader with whichwe were familiar,immediately attracted our attention. We moved closer and tried unsuccessfullyto photographit. Shortlythereafter all the birdspresent took to the air. The sandpiperflew out over the dunesbut curvedback and landedout of sighton the open beach. We telephonedRobin Roberson,and half an hour later she, Brian Weed, Jan Scott, Bob Tinfie, and Ron Branson arrived,the lattertwo armedwith telephotolenses. We quicklyrelocated the TerekSandpiper on the beach,foraging at the surfline. The followingdescription is basedon our field notes,with color names takenfrom Smithe(197.5). Our bird was a medium-sizedsandpiper resemblinga winter-plumagedSpotted Sandpiper (Actitis rnacularia)but distinguishedby bright yellow-orangelegs and an upturnedbill (Figure1). The evenlycurved, dark horn bill, 1.5 timesthe lengthof the bird'shead, had a fleshyorange base. -

Hatching Dates for Common Sandpiper <I>Actitis Hypoleucos</I

Hatching dates for Common Sandpiper Actitis hypoleucos chicks - variation with place and time T.W. Dougall, P.K. Holland& D.W. Yalden Dougall,T.W., Holland,P.K. & Yalden, D.W. 1995. Hatchingdates for CommonSandpiper Actitishypoleucos chicks - variationwith place and time. WaderStudy Group Bull. 76: 53-55. CommonSandpiper chicks hatched in 1990-94between 24 May (year-day146) and 13 July (year-day196), butthe averagehatch-date was variablebetween years, up to 10 days earlier in 1990 than in 1991. There are indicationsthat on average CommonSandpipers hatch a few days earlierin the Borders,the more northerlysite, butthis may reflecta changein the age structureof the Peak Districtpopulation between the 1970sand the 1980s- 1990s,perhaps the indirectconsequence of the bad weatherof April 1981. Dougall,T. W., 29 LaudstonGardens, Edinburgh EH3 9HJ, UK. Holland,P. K., 2 Rennie Court,Brettargh Drive, LancasterLA 1 5BN, UK. Yalden,D. W., Schoolof BiologicalSciences, University, Manchester M13 9PT, UK. INTRODUCTION Yalden(1991a) in calculatingthe originalregression, and comingfrom the years 1977-1989 (mostlythe 1980s). CommonSandpipers Actitis hypoleucos have a short We also have, for comparison,the knownhatch dates for breedingseason, like mostwaders; arriving back from 49 nestsreported by Hollandet al. (1982), comingfrom West Africa in late April, most have laid eggs by mid-May, various sites in the Peak District in the 1970s. which hatch around mid-June. Chicksfledge by early July, and by mid-Julymost breedingterritories are Ringingactivities continue through the breedingseason at deserted(Holland et al. 1982). The timingof the breeding both sites, and chickscan be at any age from 0 to 19 days season seems constantfrom year to year, but there are old when caught (thoughyoung chicks are generally few data to quantifythis impression.It is difficultto locate easier to find). -

International Single Species Action Plan for the Conservation of the Spoon-Billed Sandpiper (Eurynorhynchus Pygmeus)

CMS Technical Report Series No. 23 International Single Species Action Plan for the Conservation of the Spoon-billed Sandpiper (Eurynorhynchus pygmeus) Authors: Christoph Zöckler (ArcCona Ecological Consulting), Evgeny E. Syroechkovskiy Jr.(Russian Bird Conservation Union & Russian Academy of Sciences) , Gillian Bunting (ArcCona Ecological Consulting) Published by BirdLife International and the Secretariat of the Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals (CMS) Citation: C. Zöckler, E.E. Syroechkovskiy, Jr. and G. Bunting. International Single Species Action Plan for the Conservation of the Spoon-billed Sandpiper (Eurynorhynchus pygmeus) 2010 BirdLife International Asia Division, Tokyo, Japan; CMS Secretariat, Bonn, Germany.52pages. Technical Report Series 23 © 2010 BirdLife International and CMS. This publication, except the cover photograph, may be reproduced in whole or in part and in any form for educational and other non-profit purposes without special permission from the copyright holder, provided acknowledgement of the source is made. BirdLife International and CMS would appreciate receiving a copy of any publication that uses this publication as a source. No use of this publication may be made for resale or for any other commercial purposes whatsoever without prior permission from the copyright holders. Disclaimer The contents of this volume do not necessary reflect the views of BirdLife International and CMS. The designations employed and the presentation do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of BirdLife International or CMS concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area in its authority, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Copies of this publication are available from the following websites BirdLife International: www.birdlife.org BirdLife International Asia Division: www.birdlife-asia.org/eng/about/index.html CMS Secretariat: www.cms.int BirdLife International, Wellbrook Court, Girton Road, Cambridge CB3 0NA, United Kingdom. -

Calidris Himantopus (Stilt Sandpiper)

UWI The Online Guide to the Animals of Trinidad and Tobago Behaviour Calidris himantopus (Stilt sandpiper) Family: Scolopacidae (Sandpipers) Order: Charadriiformes (Shorebirds and Waders) Class: Aves (Birds) Fig 1. Stilt sandpiper, Calidris himantopus http://www.arkive.org/stilt-sandpiper/calidris-himantopus/image-G86449.html TRAITS. Stilt sandpipers on average are 20.3 – 23 cm in length, weigh 55g and have a life expectancy of about 11 years. In general, the males are more slender than females and have a long neck with a thin, black decurved bill that droops at the tip and long, dull green legs (Hilty, 2002). Female stilt sandpipers are slightly larger than their male counterparts and possess a brown ventral barring (Fig. 1) (Jehl Jr 1973). The non-breeding plumage of these birds consists of the upper body part being mostly plain grey with a white patch on its rump while the lower part of the body is white. In addition, the fore neck and sides of the chest are smudged grey (Hilty, 2002). The breeding plumage differs from the non-breeding plumage. The upper body turns a greyish brown while the lower body turns a dirty white. Additionally, the crown and UWI The Online Guide to the Animals of Trinidad and Tobago Behaviour cheeks are reddish brown, there is the presence of a narrow white eyebrow stripe and the under parts of the body are black in colour (Hilty, 2002). Juveniles have an upper body that is scaled buff with the fore neck and sides of the chest containing fine grey streaks (Hilty, 2002). ECOLOGY. -

Rangewide Patterns of Migratory Connectivity in the Western

Journal of Avian Biology 43: 155–167, 2012 doi: 10.1111/j.1600-048X.2012.05573.x © 2012 Th e Authors. Journal of Avian Biology © 2012 Nordic Society Oikos Subject Editor: Th eunis Piersma. Accepted 16 January 2012 Range-wide patterns of migratory connectivity in the western sandpiper Calidris mauri Samantha E. Franks , D. Ryan Norris , T. Kurt Kyser , Guillermo Fern á ndez , Birgit Schwarz , Roberto Carmona , Mark A. Colwell , Jorge Correa Sandoval , Alexey Dondua , H. River Gates , Ben Haase , David J. Hodkinson , Ariam Jim é nez , Richard B. Lanctot , Brent Ortego , Brett K. Sandercock , Felicia Sanders , John Y. Takekawa , Nils Warnock, Ron C. Ydenberg and David B. Lank S. E. Franks ([email protected]), B. Schwarz, A. Jiménez, R. C. Ydenberg and D. B. Lank, Centre for Wildlife Ecology, Dept of Biological Sciences, Simon Fraser Univ., Burnaby, BC V5A 1S6, Canada. AJ also at: Facultad de Biología, Univ. de La Habana, Havana 10400, Cuba . – D. R. Norris, Dept of Integrative Biology, Univ. of Guelph , Guelph, ON N1G 2W1, Canada. – T. K. Kyser, Queen ’ s Facility for Isotope Research, Dept of Geological Sciences and Geological Engineering, Queen ’ s Univ., Kingston, ON K7L 3N6, Canada. – G. Fernández, Unidad Acad é mica Mazatl á n, Inst. de Ciencias del Mar y Limnolog í a, Univ. Nacional Aut ó noma de M é xico, Mazatl á n, Sinaloa 82040, M é xico. – R. Carmona, Depto de Biolog í a Marina, Univ. Aut ó noma de Baja California Sur, La Paz, Baja California Sur 23081, M é xico. – M. A. Colwell, Dept of Wildlife, Humboldt State Univ., Arcata, CA 95521, USA .