Introduction: Tradition and Transition in Contemporary Irish Fiction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Subversion in Robert Mcliam Wilson's Ripley Bogle

“Down-and-Outs, Subways and Suburbs: Subversion in Robert McLiam Wilson’s Ripley Bogle (1989) and Colum McCann’s This Side of Brightness (1998)” Marie Mianowski To cite this version: Marie Mianowski. “Down-and-Outs, Subways and Suburbs: Subversion in Robert McLiam Wilson’s Ripley Bogle (1989) and Colum McCann’s This Side of Brightness (1998)”. Rodopi. Sub-versions: Transnational Readings of Modern Irish Literature. Ciaran Ross, ed., pp.87-100, 2010, 9789042028289 9042028289 9789042028296 9042028297. hal-01913551 HAL Id: hal-01913551 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01913551 Submitted on 19 Nov 2018 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Marie Mianowski – Nantes University, France - "Down-and-outs, subways and suburbs: subversion in Robert McLiam Wilson’s Ripley Bogle (1989) and Colum McCann’s This Side of Brightness (1998)" Robert McLiam Wilson’s Ripley Bogle (1989) and Colum McCann’s This Side of Brightness (1998) both point to fundamental common issues as far as the notion of subversion is concerned. McLiam Wilson’s eponymous hero is a young Irish tramp wandering in London, who has often been compared to Joyce's Bloom by reviewers. -

Fragmentation and Vulnerability in Anne Enright´S the Green Road (2015): Collateral Casualties of the Celtic Tiger in Ireland

International Journal of IJES English Studies UNIVERSITY OF MURCIA http://revistas.um.es/ijes Fragmentation and vulnerability in Anne Enright´s The Green Road (2015): Collateral casualties of the Celtic Tiger in Ireland MARIA AMOR BARROS-DEL RÍO* Universidad de Burgos (Spain) Received: 14/12/2016. Accepted: 26/05/2017. ABSTRACT This article explores the representation of family and individuals in Anne Enright's novel The Green Road (2015) by engaging with Bauman's sociological category of “liquid modernity” (2000). In The Green Road, Enright uses a recurrent topic, a family gathering, to observe the multiple forms in which particular experiences seem to have suffered a process of fragmentation during the Celtic Tiger period. A comprehensive analysis of the form and plot of the novel exposes the ideological contradictions inherent in the once hegemonic notion of Irish family and brings attention to the different forms of individual vulnerability, aging in particular, for which Celtic Tiger Ireland has no answer. KEYWORDS: Anne Enright, The Green Road, Ireland, contemporary fiction, Celtic Tiger, mobility, fragmentation, vulnerability, aging. 1. INTRODUCTION Ireland's central decades of the 20th century featured a nationalism characterized by self- sufficiency and a marked protectionist policy. This situation changed in the 1960s and 1970s when external cultural influences through the media, growing flows of migration and economic transformations initiated by the government, together with the weakening of the Welfare State, progressively transformed a rural new-born country into an international _____________________ *Address for correspondence: María Amor Barros-del Río. Departamento de Filología. Facultad de Humanidades y Comunicación. Paseo de los Comendadores s/n. -

The Immigrant in Contemporary Irish Literature

From Byzantium to Ballymun A review of Literary visions of multicultural Ireland: the immigrant in contemporary Irish literature. Ed. Pilar Villar-Argáiz. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2014. Pb 2015. 273 pps. A book like Literary visions of multicultural Ireland: the immigrant in contemporary Irish literature has been long-awaited, and since its publication the topic of migrations has become more burning than ever. That the phenomenon of immigration is more striking in Ireland than in many other countries is due to several factors, the most striking of which would be that Ireland has (1) known a centuries-long history of emigration, (2) an almost equally long history of being colonized and (3) a small population on a much divided island. In The Ex-Isle of Erin (1997) O’Toole punningly catches the inversion of the above situation as the tradition of ‘exile’ has been replaced by mass immigration while the country has been ‘un-islanded’ in its embrace by the EU’s vaster network of (mainly) continental countries. This densely printed book contains 18 contributions divided over four parts: Part I deals with ‘Irish multiculturalisms: obstacles and challenges’; Part II ‘‘Rethink[s] Ireland’ as a postnationalist community’; Part III focuses on ‘‘The return of the repressed’: ‘performing’ Irishness through intercultural encounters’; Part IV, finally, looks at ‘Gender and the city’. In this review I will first present the Irish sociological background as sketched by the contributors, then discuss each of the literary genres scrutinized in this book and conclude with a general assessment. That Ireland has undergone major changes since Mary Robinson became president is obvious. -

New Writing from Ireland

New Writing from Ireland Promoting Irish Literature Abroad Fiction | 1 NEW WRITING FROM ireLAND 2013 This is a year of new beginnings – Ireland first published 2013 Impac Award-winner Literature Exchange has moved offices Kevin Barry’s collection, There Are Little and entered into an exciting partnership Kingdoms in 2007, offers us stories from with the Centre for Literary Translation at Colin Barrett. Trinity College, Dublin. ILE will now have more space to host literary translators from In the children and young adult section we around the world and greater opportunities have debut novels by Katherine Farmar and to organise literary and translation events Natasha Mac a’Bháird and great new novels in co-operation with our partners. by Oisín McGann and Siobhán Parkinson. Writing in Irish is also well represented and Regular readers of New Writing from Ireland includes Raic/Wreck by Máire Uí Dhufaigh, will have noticed our new look. We hope a thrilling novel set on an island on the these changes make our snapshot of Atlantic coast. contemporary Irish writing more attractive and even easier to read! Poetry and non-fiction are included too. A new illustrated book of The Song of Contemporary Irish writing also appears Wandering Aengus by WB Yeats is an exciting to be undergoing a renaissance – a whole departure for the Futa Fata publishing house. 300 pp range of intriguing debut novels appear Leabhar Mór na nAmhrán/The Big Book of this year by writers such as Ciarán Song is an important compendium published Collins, Niamh Boyce, Paul Lynch, Frank by Cló Iar-Chonnacht. -

On the Margin of Cities. Representation of Urban Space in Contemporary Irish and British Fiction Philippe Laplace, Eric Tabuteau

Cities on the Margin; On the Margin of Cities. Representation of Urban Space in Contemporary Irish and British Fiction Philippe Laplace, Eric Tabuteau To cite this version: Philippe Laplace, Eric Tabuteau. Cities on the Margin; On the Margin of Cities. Representation of Urban Space in Contemporary Irish and British Fiction. 2003. hal-02320291 HAL Id: hal-02320291 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02320291 Submitted on 14 Nov 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Cities on the Margin; On the Margin of Cities 7 TABLE OF CONTENTS Gérard BREY (University of Franche-Comté, Besançon), Foreword ..... 9 Philippe LAPLACE & Eric TABUTEAU (University of Franche- Comté, Besançon), Cities on the Margin; On the Margin of Cities ......... 11 Richard SKEATES (Open University), "Those vast new wildernesses of glass and brick:" Representing the Contemporary Urban Condition ......... 25 Peter MILES (University of Wales, Lampeter), Road Rage: Urban Trajectories and the Working Class ............................................................ 43 Tim WOODS (University of Wales, Aberystwyth), Re-Enchanting the City: Sites and Non-Sites in Urban Fiction ................................................ 63 Eric TABUTEAU (University of Franche-Comté, Besançon), Marginally Correct: Zadie Smith's White Teeth and Sam Selvon's The Lonely Londoners .................................................................................... -

The Role of Irish-Language Film in Irish National Cinema Heather

Finding a Voice: The Role of Irish-Language Film in Irish National Cinema Heather Macdougall A Thesis in the PhD Humanities Program Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at Concordia University Montreal, Quebec, Canada August 2012 © Heather Macdougall, 2012 ABSTRACT Finding a Voice: The Role of Irish-Language Film in Irish National Cinema Heather Macdougall, Ph.D. Concordia University, 2012 This dissertation investigates the history of film production in the minority language of Irish Gaelic. The objective is to determine what this history reveals about the changing roles of both the national language and national cinema in Ireland. The study of Irish- language film provides an illustrative and significant example of the participation of a minority perspective within a small national cinema. It is also illustrates the potential role of cinema in language maintenance and revitalization. Research is focused on policies and practices of filmmaking, with additional consideration given to film distribution, exhibition, and reception. Furthermore, films are analysed based on the strategies used by filmmakers to integrate the traditional Irish language with the modern medium of film, as well as their motivations for doing so. Research methods included archival work, textual analysis, personal interviews, and review of scholarly, popular, and trade publications. Case studies are offered on three movements in Irish-language film. First, the Irish- language organization Gael Linn produced documentaries in the 1950s and 1960s that promoted a strongly nationalist version of Irish history while also exacerbating the view of Irish as a “private discourse” of nationalism. Second, independent filmmaker Bob Quinn operated in the Irish-speaking area of Connemara in the 1970s; his fiction films from that era situated the regional affiliations of the language within the national context. -

7 1Stephen A

SLIPSTREAM A DATA RICH PRODUCTION ENVIRONMENT by Alan Lasky Bachelor of Fine Arts in Film Production New York University 1985 Submitted to the Media Arts & Sciences Section, School of Architecture & Planning in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology September, 1990 c Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 1990 All Rights Reserved I Signature of Author Media Arts & Sciences Section Certified by '4 A Professor Glorianna Davenport Assistant Professor of Media Technology, MIT Media Laboratory Thesis Supervisor Accepted by I~ I ~ - -- 7 1Stephen A. Benton Chairperso,'h t fCommittee on Graduate Students OCT 0 4 1990 LIBRARIES iznteh Room 14-0551 77 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02139 Ph: 617.253.2800 MITLibraries Email: [email protected] Document Services http://libraries.mit.edu/docs DISCLAIMER OF QUALITY Due to the condition of the original material, there are unavoidable flaws in this reproduction. We have made every effort possible to provide you with the best copy available. If you are dissatisfied with this product and find it unusable, please contact Document Services as soon as possible. Thank you. Best copy available. SLIPSTREAM A DATA RICH PRODUCTION ENVIRONMENT by Alan Lasky Submitted to the Media Arts & Sciences Section, School of Architecture and Planning on August 10, 1990 in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science ABSTRACT Film Production has always been a complex and costly endeavour. Since the early days of cinema, methodologies for planning and tracking production information have been constantly evolving, yet no single system exists that integrates the many forms of production data. -

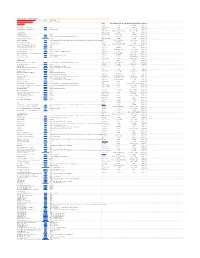

THANKSGIVING and BLACK FRIDAY STORE HOURS --->> ---> ---> Always Do a Price Comparison on Amazon Here Store Price Notes

THANKSGIVING AND BLACK FRIDAY STORE HOURS --->> ---> ---> Always do a price comparison on Amazon Here Store Price Notes KOHL's Coupon Codes: $15SAVEBIG15 Kohl's Cash 15% for everyoff through $50 spent 11/24 through 11/25 Electronics Store Thanksgiving Day Store HoursBlack Friday Store Hours Confirmed DVD PLAYERS AAFES Closed 4:00 AM Projected RCA 10" Dual Screen Portable DVD Player Walmart $59.00 Ace Hardware Open Open Confirmed Sylvania 7" Dual-Screen Portable DVD Player Shopko $49.99 Doorbuster Apple Closed 8 am to 10 pm Projected Babies"R"Us 5 pm to 11 pm on Friday Closes at 11 pm Projected BLU-RAY PLAYERS Barnes & Noble Closed Open Confirmed LG 4K Blu-Ray Disc Player Walmart $99.00 Bass Pro Shops 8 am to 6 pm 5:00 AM Confirmed LG 4K Ultra HD 3D Blu-Ray Player Best Buy $99.99 Deals online 11/24 at 12:01am, Doors open at 5pm; Only at Best Buy Bealls 6 pm to 11 pm 6 am to 10 pm Confirmed LG 4K Ultra-HD Blu-Ray Player - Model UP870 Dell Home & Home Office$109.99 Bed Bath & Beyond Closed 6:00 AM Confirmed Samsung 4K Blu-Ray Player Kohl's $129.99 Shop Doorbusters online at 12:01 a.m. (CT) Thursday 11/23, and in store Thursday at 5 p.m.* + Get $15 in Kohl's Cash for every $50 SpentBelk 4 pm to 1 am Friday 6 am to 10 pm Confirmed Samsung 4K Ultra Blu-Ray Player Shopko $169.99 Doorbuster Best Buy 5:00 PM 8:00 AM Confirmed Samsung Blu-Ray Player with Built-In WiFi BJ's $44.99 Save 11/17-11/27 Big Lots 7 am to 12 am (midnight) 6:00 AM Confirmed Samsung Streaming 3K Ultra HD Wired Blu-Ray Player Best Buy $127.99 BJ's Wholesale Club Closed 7 am -

The Historical Development of Irish Euroscepticism to 2001

The Historical Development of Irish Euroscepticism to 2001 Troy James Piechnick Thesis submitted as part of the Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) program at Flinders University on the 1st of September 2016 Social and Behavioural Sciences School of History and International Relations Flinders University 2016 Supervisors Professor Peter Monteath (PhD) Dr Evan Smith (PhD) Associate Professor Matt Fitzpatrick (PhD) Contents GLOSSARY III ABSTRACT IV ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS V CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION 1 DEFINITIONS 2 PARAMETERS 13 LITERATURE REVIEW 14 MORE RECENT DEVELOPMENTS 20 THESIS AND METHODOLOGY 24 STRUCTURE 28 CHAPTER 2 EARLY ANTECEDENTS OF IRISH EUROSCEPTICISM: 1886–1949 30 IRISH REPUBLICANISM, 1780–1886 34 FIRST HOME RULE BILL (1886) AND SECOND HOME RULE BILL (1893) 36 THE BOER WAR, 1899–1902 39 SINN FÉIN 40 WORLD WAR I AND EASTER RISING 42 IRISH DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENCE 46 IRISH WAR OF INDEPENDENCE 1919 AND CIVIL WAR 1921 47 BALFOUR DECLARATION OF 1926 AND THE STATUTE OF WESTMINSTER IN 1931 52 EAMON DE VALERA AND WORLD WAR II 54 REPUBLIC OF IRELAND ACT 1948 AND OTHER IMPLICATIONS 61 CONCLUSION 62 CHAPTER 3 THE TREATY OF ROME AND FAILED APPLICATIONS FOR MEMBERSHIP IN 1961 AND 1967 64 THE TREATY OF ROME 67 IRELAND IN THE 1950S 67 DEVELOPING IRISH EUROSCEPTICISM IN THE 1950S 68 FAILED APPLICATIONS FOR MEMBERSHIP IN 1961 AND 1967 71 IDEOLOGICAL MAKINGS: FURTHER DEVELOPMENTS OF A EUROSCEPTIC NATURE (1960S) 75 Communist forms of Irish euroscepticism 75 Irish eurosceptics and republicanism 78 Irish euroscepticism accommodating democratic socialism 85 -

New Writing from Irelandfromwriting New New Writing from Ireland Ireland Literatureirelandexchange

New Writing from Ireland New Writing from Ireland Ireland Literature Exchange Ireland Literature Ireland Literature Exchange – Promoting Irish literature abroad Welcome Welcome to the 2007 edition of New Writing from Ireland This year’s expanded catalogue contains an even wider cross-section of newly Finally, there are poetry collections by some of Ireland’s most established poets published titles of Irish interest. - Peter Fallon, Seán Lysaght, Gerard Smyth, Francis Harvey, Liam Ó Muirthile and Cathal Ó Searcaigh. New collections also appear from a generation of The fiction section includes novels by several new voices including débuts younger poets, including Nick Laird, John McAuliffe, Alan Gillis and from Karen Ardiff, Alice Chambers and Julia Kelly. We also list books by a Mary O’Donoghue. number of established and much-loved authors, e.g. Gerard Donovan, Patrick McCabe and Joseph O’Connor, and we are particularly pleased this year to We hope that you enjoy the catalogue and that many international publishers present a new collection by the short story writer, Claire Keegan, and a new will apply to Ireland Literature Exchange for translation funding. play by Sebastian Barry. Sinéad Mac Aodha Rita McCann Children’s books have always been a particular strength of Irish writing. There Director Programme Officer are books here from, amongst others, Conor Kostick, Deirdre Madden, Eileen O’Hely and Enda Wyley. A former magician’s rabbit, a mysterious notebook, giant venomous spiders and a trusted pencil are just some of the more colourful elements to be found in the children’s fiction category. Inclusion of a book in this catalogue does not indicate that it has been approved for a translation subsidy by ILE. -

Irish Identity in Seamus Deane's Reading in the Dark Peter Jasinski

Inscape Volume 21 | Number 2 Article 6 10-1-2001 Irish Identity in Seamus Deane's Reading in the Dark Peter Jasinski Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/inscape Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Jasinski, Peter (2001) "Irish Identity in Seamus Deane's Reading in the Dark," Inscape: Vol. 21 : No. 2 , Article 6. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/inscape/vol21/iss2/6 This Essay is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Inscape by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. IRISH IDENTITY IN SEAMUS DEANE'S READING IN THE DARK Peter Jasinski n Seamus Deane's Reading in the Dark, Deane presents us with the Ichildhood of an unnamed narrator who tells the story of his troubled family in postwar Northern Ireland. As the boy stumbles through the complexities and ironies of the adult world, he slowly increases in social and political awareness. The novel takes its title from a scene in which the boy, after the lights are turned off, tries to imagine the story he had been reading. The image of reading in the dark expresses the difficulty of reconstructing the past from fragmen tary accounts available in the present: the narrator's family history "came to [him] in bits, from people who rarely recognized all they had told" (236). He uncovers only a partial picture of the truth as he tries to put together the tragic, mysterious past of his family. -

Downloaded from Downloaded on 2020-06-06T01:34:25Z Ollscoil Na Héireann, Corcaigh

UCC Library and UCC researchers have made this item openly available. Please let us know how this has helped you. Thanks! Title A cultural history of The Great Book of Ireland – Leabhar Mór na hÉireann Author(s) Lawlor, James Publication date 2020-02-01 Original citation Lawlor, J. 2020. A cultural history of The Great Book of Ireland – Leabhar Mór na hÉireann. PhD Thesis, University College Cork. Type of publication Doctoral thesis Rights © 2020, James Lawlor. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Item downloaded http://hdl.handle.net/10468/10128 from Downloaded on 2020-06-06T01:34:25Z Ollscoil na hÉireann, Corcaigh National University of Ireland, Cork A Cultural History of The Great Book of Ireland – Leabhar Mór na hÉireann Thesis presented by James Lawlor, BA, MA Thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy University College Cork The School of English Head of School: Prof. Lee Jenkins Supervisors: Prof. Claire Connolly and Prof. Alex Davis. 2020 2 Table of Contents Abstract ............................................................................................................................... 4 Declaration .......................................................................................................................... 5 Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................ 6 List of abbreviations used ................................................................................................... 7 A Note on The Great