Rethinking Chinese Internet Fictions, TV Series, and Cultural Landscape Via the Case of the List of Langya (Langya Bang, 瑯琊榜)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ancient Allure Seen Through a Screen

22 | Thursday, July 25, 2019 HONG KONG EDITION | CHINA DAILY LIFE Ancient allure seen through a screen The popularity of a recent online Popular tour sites drama staged in Top scenic areas in Xi’an in the Tang Dynasty summer 1. Emperor Qinshihuang’s has translated into Mausoleum Site Museum a surge of visitors 2. Xi’an City Walls 3. Tang Paradise Theme Park to Xi’an, 4. Shaanxi History Museum 5. Muslim Street Xu Lin reports. 6. Huaqing Palace 7. North Square of Giant Wild he hit thriller series, The Goose Pagoda Longest Day in Chang’an, 8. Daming Palace National takes viewers to the heyday Heritage Park of the Tang Dynasty (618 9. Yongxing Fang T907). And since its premiere on June 10. Sleepless City of Tang 27, it has been creating a new heyday for Xi’an’s travel sector and interest SOURCE: MAFENGWO in its past. In the online drama, a deathrow Top domestic filming spots as inmate, played by actor Lei Jiayin, summer destinations accepts a mission from a govern 1. Xi’an, Shaanxi province ment official, played by singeractor 2. Suzhou, Jiangsu province Yi Yangqianxi, during Lantern Festi 3. Chongqing val. The condemned criminal must 4. Zhangjiajie, Hunan province save the national capital, Chang’an, 5. Nanjing, Jiangsu province from a secret enemy attack within 24 6. Shanghai hours. Chang’an is today Shaanxi’s 7. Qingdao, Shandong province provincial capital, Xi’an. 8. Dongyang, Zhejiang province The show’s extreme popularity 9. Bayanbulak Grassland, Xinji has intensified interest in travel to ang Uygur autonomous region Xi’an. -

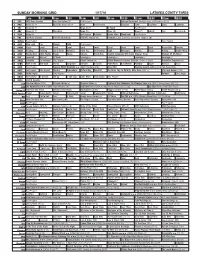

Sunday Morning Grid 1/17/16 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 1/17/16 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program College Basketball Michigan State at Wisconsin. (N) Å 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News Paid Program Clangers Luna! LazyTown Luna! LazyTown 5 CW News (N) Å News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) News Å Liberty Paid Eye on L.A. 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Pastor Mike Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Kickoff (N) FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football Seattle Seahawks at Carolina Panthers. (N) 13 MyNet Paid Program Paid Program 18 KSCI Man Land Paid Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Cosas Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local RescueBot Transfor. 24 KVCR Painting Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Oil Painting Cook Moveable Martha Pépin Baking Simply Ming 28 KCET Wunderkind 1001 Nights Raggs Space Edisons Travel-Kids Soulful Symphony With Darin Atwater: Song Motown 25 My Music 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Leverage Å Leverage Å Leverage Å Leverage Å 34 KMEX Conexión En contacto Paid Program Fútbol Central (N) Fútbol Mexicano Primera División: Pumas vs Toluca República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Schuller In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Pathway Super Kelinda Jesse 46 KFTR Paid Program Race to Witch Mountain ›› (2009, Aventura) (PG) Zona NBA Treasure Guards (2011) Anna Friel, Raoul Bova. -

0Ca60ed30ebe5571e9c604b661

Mark Parascandola ONCE UPON A TIME IN SHANGHAI Cofounders: Taj Forer and Michael Itkoff Creative Director: Ursula Damm Copy Editors: Nancy Hubbard, Barbara Richard © 2019 Daylight Community Arts Foundation Photographs and text © 2019 by Mark Parascandola Once Upon a Time in Shanghai and Notes on the Locations © 2019 by Mark Parascandola Once Upon a Time in Shanghai: Images of a Film Industry in Transition © 2019 by Michael Berry All rights reserved. ISBN 978-1-942084-74-7 Printed by OFSET YAPIMEVI, Istanbul No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior permission in writing of copyright holders and of the publisher. Daylight Books E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.daylightbooks.org 4 5 ONCE UPON A TIME IN SHANGHAI: IMAGES OF A FILM INDUSTRY IN TRANSITION Michael Berry THE SOCIALIST PERIOD Once upon a time, the Chinese film industry was a state-run affair. From the late centers, even more screenings took place in auditoriums of various “work units,” 1940s well into the 1980s, Chinese cinema represented the epitome of “national as well as open air screenings in many rural areas. Admission was often free and cinema.” Films were produced by one of a handful of state-owned film studios— tickets were distributed to employees of various hospitals, factories, schools, and Changchun Film Studio, Beijing Film Studio, Shanghai Film Studio, Xi’an Film other work units. While these films were an important part of popular culture Studio, etc.—and the resulting films were dubbed in pitch-perfect Mandarin during the height of the socialist period, film was also a powerful tool for education Chinese, shot entirely on location in China by a local cast and crew, and produced and propaganda—in fact, one could argue that from 1949 (the founding of the almost exclusively for mainland Chinese film audiences. -

Hengten Networks (00136.HK)

22-Feb-2021 ︱Research Department HengTen Networks (00136.HK) SBI China Capital Research Department T: +852 2533 3700 Initiation: China’s Netflix backed by Evergrande and Tencent E: [email protected] ◼ Transforming into a leading online long-video platform with similar Address: 4/F, Henley Building, No.5 Queen's DNA to Netflix. Road Central, Hong Kong ◼ As indicated by name, HengTen (HengDa and Tencent) (136.HK) will leverage the resources of its two significant shareholders in making Ticker (00136.HK) Pumpkin Film the most profitable market leader Recommendation BUY ◼ New team has proven track record in original content production Target price (HKD) 24.0 with an extensive pipeline. Current price (HKD) 13.8 ◼ Initiate BUY with TP HK$24.0 based on 1.0x PEG, representing 74% Last 12 mth price range 0.62 – 17.80 upside potential. Market cap. (HKD, bn) 127.8 Source: Bloomberg, SBI CHINA CAPITAL Transforming into a leading online long-video platform with similar DNA to Netflix. HengTen Networks (“HT”) (136.HK) announced to acquire an 100% stake in Virtual Cinema Entertainment Limited. The company has two main business lines: “Shanghai Ruyi” engages in film and TV show production while “Pumpkin Film”operates an online video platform. Currently one of the only two profitable online video platforms, we expect the company to enjoy similar success as Netflix given their common genes such as: a) a highly successful and proven content development team b) focus on big data analytics which improves ROI visibility and c) enjoyable user experience with an ads-free subscription model As indicated by name, HengTen (HengDa and Tencent) (136.HK) will leverage the resources of its two significant shareholders in making Pumpkin Film the most profitable market leader. -

1 Before the U.S. COPYRIGHT OFFICE, LIBRARY of CONGRESS

Before the U.S. COPYRIGHT OFFICE, LIBRARY OF CONGRESS In the Matter of Exemption to Prohibition on Circumvention of Copyright Protection Systems for Access Control Technologies Under 17 U.S.C. §1201 Docket No. 2014-07 Reply Comments of the Electronic Frontier Foundation 1. Commenter Information Mitchell L. Stoltz Corynne McSherry Kit Walsh Electronic Frontier Foundation 815 Eddy St San Francisco, CA 94109 (415) 436-9333 [email protected] The Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF) is a member-supported, nonprofit public interest organization devoted to maintaining the traditional balance that copyright law strikes between the interests of rightsholders and the interests of the public. Founded in 1990, EFF represents over 25,000 dues-paying members, including consumers, hobbyists, artists, writers, computer programmers, entrepreneurs, students, teachers, and researchers, who are united in their reliance on a balanced copyright system that ensures adequate incentives for creative work while promoting innovation, freedom of speech, and broad access to information in the digital age. In filing these reply comments, EFF represents the interests of the many people in the U.S. who have “jailbroken” their cellular phone handsets and other mobile computing devices—or would like to do so—in order to use lawfully obtained software of their own choosing, and to remove software from the devices. 2. Proposed Class 16: Jailbreaking – wireless telephone handsets Computer programs that enable mobile telephone handsets to execute lawfully obtained software, where circumvention is accomplished for the sole purposes of enabling interoperability of such software with computer programs on the device or removing software from the device. 1 3. -

Chapter 2. Analysis of Korean TV Dramas

저작자표시-비영리-변경금지 2.0 대한민국 이용자는 아래의 조건을 따르는 경우에 한하여 자유롭게 l 이 저작물을 복제, 배포, 전송, 전시, 공연 및 방송할 수 있습니다. 다음과 같은 조건을 따라야 합니다: 저작자표시. 귀하는 원저작자를 표시하여야 합니다. 비영리. 귀하는 이 저작물을 영리 목적으로 이용할 수 없습니다. 변경금지. 귀하는 이 저작물을 개작, 변형 또는 가공할 수 없습니다. l 귀하는, 이 저작물의 재이용이나 배포의 경우, 이 저작물에 적용된 이용허락조건 을 명확하게 나타내어야 합니다. l 저작권자로부터 별도의 허가를 받으면 이러한 조건들은 적용되지 않습니다. 저작권법에 따른 이용자의 권리는 위의 내용에 의하여 영향을 받지 않습니다. 이것은 이용허락규약(Legal Code)을 이해하기 쉽게 요약한 것입니다. Disclaimer Master’s Thesis of International Studies The Comparison of Television Drama’s Production and Broadcast between Korea and China 중한 드라마의 제작 과 방송 비교 August 2019 Graduate School of International Studies Seoul National University Area Studies Sheng Tingyin The Comparison of Television Drama’s Production and Broadcast between Korea and China Professor Jeong Jong-Ho Submitting a master’s thesis of International Studies August 2019 Graduate School of International Studies Seoul National University International Area Studies Sheng Tingyin Confirming the master’s thesis written by Sheng Tingyin August 2019 Chair 박 태 균 (Seal) Vice Chair 한 영 혜 (Seal) Examiner 정 종 호 (Seal) Abstract Korean TV dramas, as important parts of the Korean Wave (Hallyu), are famous all over the world. China produces most TV dramas in the world. Both countries’ TV drama industries have their own advantages. In order to provide meaningful recommendations for drama production companies and TV stations, this paper analyzes, determines, and compares the characteristics of Korean and Chinese TV drama production and broadcasting. -

Case Study TV Programming August 2014

Case Study TV Programming August 2014 Strictly Confidential: If you are interested in learning more, please contact e: [email protected] www.ipsos.comwww.ipsos.com/mediact/mediact 2 Consumer decision-making in TV channels Strictly Confidential: If you are interested in learning more, please contact e: [email protected] www.ipsos.com/mediact 3 Pick Me! To diagnose and build stand out and appeal Strictly Confidential: If you are interested in learning more, please contact e: [email protected] www.ipsos.com/mediact The Blacklist is a newer series but performs well with both viewers and non- viewers. It scores as well as NCIS – the top US ratings series now in its 11th season. 4 Strictly Confidential: If you are interested in learning more, please contact e: [email protected] www.ipsos.com/mediact When audience share is taken into account, The Blacklist shows high potential for increase while NCIS is saturated. 5 Strictly Confidential: If you are interested in learning more, please contact e: [email protected] www.ipsos.com/mediact The phenomenon of Where are we going, Dad? - With only one series in, this programme has moved straight to high viewership and share – will it be able to hold onto that position? 6 Perfect Dating Laugh out Loud Life Exchage Palace Empresses in the Palace First Time Potential The Palace: the Lost Daughter Index Scarlet Heart 2 If You Are The One iPartment Dream Show Iam A Singer Economic News Happy Camp Focus Today Where are we going, Dad? News Simulcast Performance Index 8.2 3.5 Strictly Confidential: If you are interested in learning more, please contact e: [email protected] www.ipsos.com/mediact 7 Love Me! To diagnose and build engagement through emotional response and share of attention Strictly Confidential: If you are interested in learning more, please contact e: [email protected] www.ipsos.com/mediact High engagement amongst viewers for cult series The Walking Dead. -

CONTEMPORARY DANMEI FICTION and ITS SIMILITUDES with CLASSICAL and YANQING LITERATURE Fiksi Danmei Kontemporer Dan Persamaannya Dengan Sastra Klasik Dan Yanqing

Aiqing Wang CONTEMPORARY DANMEI FICTION AND ITS SIMILITUDES WITH CLASSICAL AND YANQING LITERATURE Fiksi Danmei Kontemporer dan Persamaannya dengan Sastra Klasik dan Yanqing Aiqing Wang Department of Modern Languages and Cultures University of Liverpool [email protected] Naskah diterima: 3 Februari 2021; direvisi: 31 Maret 2021 ; disetujui: 17 Juni 2021 doi: https://doi.org/10.26499/jentera.v10i1.3397 Abstract Danmei, aka Boys Love, is a salient transgressive genre of Chinese internet literature. Since entering China’s niche market in the 1990s, the danmei subculture, predominantly in the form of an original fictional creation, has established an enormous fanbase and demonstrated significance via thought-provoking works and social functions. Nonetheless, the danmei genre is not an innovation in the digital age, in that its bipartite dichotomy between seme ‘top’ and uke ‘bottom’ roles bears similarities to the dyad in caizi-jiaren ‘scholar-beauty’ anecdotes featuring masculine and feminine ideals in literary representations of heterosexual love and courtship, which can be attested in the 17th century and earlier extant accounts. Furthermore, the feminisation of danmei characters is analogous to an androgynous ideal in late-imperial narratives concerning heterosexual relationships during late Ming and early Qing dynasties. Besides, the depiction of semes being masculine while ukes being feminine is consistent with the orthodox, indigenous Chinese masculinity, which is comprised of wen ‘cultural attainment’ epitomising feminine traits and wu ‘martial valour’ epitomising masculine traits. In terms of modern literature, danmei is parallel to the (online) genre yanqing ‘romance’ that is frequently characterised by ‘Mary Sue’ and cliché-ridden narration. Keywords: danmei genre, ‘scholar-beauty’ fiction, yanqing romance, feminisation, ‘Mary Sue’ Abstrak Danmei, alias Boys Love, adalah genre transgresif yang menonjol dari sastra internet Tiongkok. -

Historical Romance and Sixteenth-Century Chinese Cultural Fantasies

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2013 Genre and Empire: Historical Romance and Sixteenth-Century Chinese Cultural Fantasies Yuanfei Wang University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the English Language and Literature Commons, and the History Commons Recommended Citation Wang, Yuanfei, "Genre and Empire: Historical Romance and Sixteenth-Century Chinese Cultural Fantasies" (2013). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 938. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/938 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/938 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Genre and Empire: Historical Romance and Sixteenth-Century Chinese Cultural Fantasies Abstract Chinese historical romance blossomed and matured in the sixteenth century when the Ming empire was increasingly vulnerable at its borders and its people increasingly curious about exotic cultures. The project analyzes three types of historical romances, i.e., military romances Romance of Northern Song and Romance of the Yang Family Generals on northern Song's campaigns with the Khitans, magic-travel romance Journey to the West about Tang monk Xuanzang's pilgrimage to India, and a hybrid romance Eunuch Sanbao's Voyages on the Indian Ocean relating to Zheng He's maritime journeys and Japanese piracy. The project focuses on the trope of exogamous desire of foreign princesses and undomestic women to marry Chinese and social elite men, and the trope of cannibalism to discuss how the expansionist and fluid imagined community created by the fiction shared between the narrator and the reader convey sentiments of proto-nationalism, imperialism, and pleasure. -

Dagbani-English Dictionary

DAGBANI-ENGLISH DICTIONARY with contributions by: Harold Blair Tamakloe Harold Lehmann Lee Shin Chul André Wilson Maurice Pageault Knut Olawski Tony Naden Roger Blench CIRCULATION DRAFT ONLY ALL COMENTS AND CORRECTIONS WELCOME This version prepared by; Roger Blench 8, Guest Road Cambridge CB1 2AL United Kingdom Voice/Answerphone/Fax. 0044-(0)1223-560687 E-mail [email protected] http://homepage.ntlworld.com/roger_blench/RBOP.htm This printout: Tamale 25 December, 2004 1. Introduction...................................................................................................................................................... 5 2. Transcription.................................................................................................................................................... 5 Vowels ................................................................................................................................................................................ 5 Consonants......................................................................................................................................................................... 6 Tones .................................................................................................................................................................................. 8 Plurals and other forms.................................................................................................................................................... 8 Variability in Dagbani -

Tencent Holdings Limited (SEHK: 700)

Initiation Company Report Internet E INDUSTRY NAM INDUSTRY INDUSTRYME Tencent vs. Alibaba: Why matter and who wins? 5 April, 2016 INVESTMENT SUMMARY ● We initiate Tencent with a BUY rating and a TP of HK$187 because we believe Research Team Tencent has an upper hand in the competition against Alibaba (BABA US, BUY, TP: US$84) to be the top Internet ecosystem in China; Tianli Wen ● Weixin has given Tencent three mandates, in our view: (1) a mobile display Head of Research interface, (2) an online-to-offline bridge and (3) a closed loop business platform. We believe the impact will result in great expansion of Tencent’s business scope; ● In the near term, we expect conversion of PC-based e-sports game to mobile, and +852 21856112 rolling out of Weixin advertising to drive growth. We project top line growth of [email protected] 39% and 26% and non-GAAP operating profit growth of 34% and 25% in 2016/17. See the last page of the report for important disclosures Blue Lotus Capital Advisors Limited 1 China|Asia ●Initiation Internet ● Multi-business Tencent Holdings Limited (SEHK: 700) Realistic imaginations: Initiate with BUY BUY HOLD SELL ● Despite being at the interlude of its growth phases, we believe Tencent’s grasp Target Price: HK$ 187 Current Price: 158.50 Initiation of the mobile Internet ecosystem warrants a BUY. RIC: (SEHK:700) BBG: 700:HK Market cap (US$ mn) 186,069 ● The potential of Weixin as an ecosystem orchestrator is still at the early stage. Average daily volume (US$ mn) 4,722 China’s entertainment spending per GDP still has big room to improve. -

The Chinese Book Market 2016

The Chinese book market 2016 [Editor's Note] An increasing number of readers have begun to show interest in this market report, which has made us very happy. Originally, this report was compiled to provide some information and suggestions for readers in the German publishing industry. Now, many readers from non-German speaking countries (including readers from Mainland China) have also asked for the English edition of the report. The 2016 report may be regarded as a supplement to the 2015 report, with additions reflected in the following three areas: 1) the latest updated figures for the Mainland China market; 2) three major trends in the Mainland China market; and 3) (for the first time!) figures for the Taiwan market. If you are planning to quote from the report, please credit the German Book Office Beijing and include “The Chinese Book Market 2016” as the title. Please notify us if you plan to quote extensively from the report. Chinese book market statistics 1. Book production and book trade According to OpenBook estimates, the Chinese book market’s total retail sales in 2015 came to some 62,4 billion yuan, an increase of 12,8% over the previous year. In addition to the retail market, there is also a market share for libraries, which, according to estimates by industry professionals, has an annual turnover of about 12 billion yuan. These two segments represent the entire Chinese book market, for a total of some 74 billion yuan. Stationary book retailing in China had an overall turnover of 34.4 billion RMB (55.13% of total share) in 2015, which amounts to an increase of 0.3% on a year-on-year basis.