Political Parties and Democracy in Theoretical and Practical Perspectives

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Anti-Imperial World Politics: Race, Class, and Internationalism in the Making of Post-Colonial Order

P a g e | 1 Anti-imperial World Politics: Race, class, and internationalism in the making of post-colonial order Christopher Patrick Murray London School of Economics and Political Science PhD. International Relations P a g e | 2 I certify that this thesis which I am presenting for examination for the PhD degree in International Relations at the London School of Economics and Political Science is solely my own work. I consider the work submitted to be a complete thesis fit for examination. I authorise that, if a degree is awarded, an electronic copy of my thesis will be deposited in LSE Theses Online (in accordance with the published deposit agreement) held by the British Library of Political and Economic Science and that, except as provided for in regulation 61 it will be made available for public reference. I authorise the School to supply a copy of the abstract of my thesis for inclusion in any published list of theses offered for higher degrees in British universities or in any supplement thereto, or for consultation in any central file of abstracts of such theses. Word count…………………………………….……….. 75, 884 P a g e | 3 ABSTRACT Anti-imperial world politics: Race, class, and internationalism in the making of post-colonial order Christopher Murray, PhD. LSE International Relations Why did many ‘black’ anti-imperial thinkers and leaders articulate projects for colonial freedom based in transnational identities and solidarities? This thesis excavates a discourse of anti-imperial globalism, which helped shape world politics from the early to late 20th century. Although usually reduced to the anticolonial nationalist politics of sovereignty and recognition, this study interprets ‘anti-imperialism globalism from below’ as a transnational counter-discourse, primarily concerned with social justice, social freedom, and equality. -

Mise En Page 1

ASIA PACIFIC NEPAL FEDERAL COUNTRY BASIC SOCIO-ECONOMIC INDICATORS INCOME GROUP: LOW INCOME LOCAL CURRENCY: NEPALESE RUPEE (NPR) POPULATION AND GEOGRAPHY ECONOMIC DATA Area: 147 180 km 2 GDP: 79 billion (current PPP international dollars), 2 697 dollars per inhabitant (2017) Population: 29.305 million inhabitants (2017), an increase of 1.2% Real GDP growth: 7.5 % (2017 vs 2016) per year (2010-2015) Unemployment rate: 2.7 % (2017) Density: 199 inhabitants / km 2 Foreign direct investment, net inflows (FDI): 196 (BoP, current USD millions, 2017) Urban population: 19.3 % of national population Gross Fixed Capital Formation (GFCF): 34% of GDP (2017) Urban population growth: 3.2 % (2017 vs 2016) HDI: 0.574 (medium), ranking 149 (2017) Capital city: Kathmandu (4.5 % of national population) Poverty rate: 15% (2010) MAIN FEATURES OF THE MULTI-LEVEL GOVERNANCE FRAMEWORK Following the end in 2006 of a decade-long civil war, Nepal’s governance framework is currently in the transition from being a Monarchy to a multiparty democratic republic. With the promulgation of the new Constitution in 2015, Nepal moved from a unitary form of government to a federal one with a strong focus on decentralization based on “cooperative federalism”. The new federation has three tiers of government, namely federal, state and local, whereby powers shall be exercised pursuant to the Constitution and the state laws. The Constitution has assigned both exclusive and concurrent powers, to be jointly exercised by the federal and the state levels or jointly by all three tiers of government. The jurisdiction of the local governments is outlined under Schedule 8 of the Constitution, which establishes that local governments are responsible for development activities and for mobilizing the necessary resources to carry out such activities. -

The Political Organisation of People Who Are Homeless: Reflections of a Sympathetic Sceptic

Part C _ Think Pieces 289 The Political Organisation of People who are Homeless: Reflections of a Sympathetic Sceptic Mike Allen Focus Ireland, Dublin, Republic of Ireland Introduction Any exploration of how poverty and social exclusion might be eradicated, and conversely of how they persist, must come to terms with the question of how people who are themselves poor are to contribute to that eradication. This contribution can be divided into two main themes : the framing of the sorts of solutions that are required and the political momentum that is necessary to put these into action. People coming from a wide range of political and conceptual positions see social movements of the poor (or representative organisations comprising the poor) capable of achieving both these objectives as the ideal manner in which poverty will be eliminated. Organisations that oppose poverty but do not involve participa- tion of the poor at their core are open to the criticism of contributing to deeper impoverishment, not only through proposing the ‘wrong’ solutions, but also by disempowering those who experience poverty. They run the risk of being charac- terised as part of the problem rather than part of the solution. Experience, however, shows that the poor are unlikely to organise around their interests in any persistent manner, and when they do come together in short-term alliances, the goals they seek to achieve are frequently short term and rarely address the underlying causes of their exclusion (Piven and Cloward, 1979). The conditions which we understand to comprise poverty – lack of resources, social isolation and powerlessness – are deprivations of the very requirements of successful organisation and of long-term thinking. -

Politician Overboard: Jumping the Party Ship

INFORMATION, ANALYSIS AND ADVICE FOR THE PARLIAMENT INFORMATION AND RESEARCH SERVICES Research Paper No. 4 2002–03 Politician Overboard: Jumping the Party Ship DEPARTMENT OF THE PARLIAMENTARY LIBRARY ISSN 1328-7478 Copyright Commonwealth of Australia 2003 Except to the extent of the uses permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means including information storage and retrieval systems, without the prior written consent of the Department of the Parliamentary Library, other than by Senators and Members of the Australian Parliament in the course of their official duties. This paper has been prepared for general distribution to Senators and Members of the Australian Parliament. While great care is taken to ensure that the paper is accurate and balanced, the paper is written using information publicly available at the time of production. The views expressed are those of the author and should not be attributed to the Information and Research Services (IRS). Advice on legislation or legal policy issues contained in this paper is provided for use in parliamentary debate and for related parliamentary purposes. This paper is not professional legal opinion. Readers are reminded that the paper is not an official parliamentary or Australian government document. IRS staff are available to discuss the paper's contents with Senators and Members and their staff but not with members of the public. Published by the Department of the Parliamentary Library, 2003 I NFORMATION AND R ESEARCH S ERVICES Research Paper No. 4 2002–03 Politician Overboard: Jumping the Party Ship Sarah Miskin Politics and Public Administration Group 24 March 2003 Acknowledgments I would like to thank Martin Lumb and Janet Wilson for their help with the research into party defections in Australia and Cathy Madden, Scott Bennett, David Farrell and Ben Miskin for reading and commenting on early drafts. -

An Environmental Ethic: Has It Taken Hold?

An Environmental Ethic: Has it Taken Hold? arth Da y n11d the creation Eof l·Y /\ i 11 1 ~l70 svrnbolized !he increasing ccrncl~rn of the nation about environmental vulues. i'\o\\'. 18 vears latur. has an cm:ironnrnntal ethic taken hold in our sot:iety'1 This issue of J\ P/\ Jounwl a<lclresscs that questi on and includes a special sc-~ct i un 0 11 n facet of the e11vironme11tal quality effort. l:nvi ron men ta I edur:alion. Thr~ issue begins with an urticln bv Pulitzer Prize-wi~rning journ;ilist and environmentalist J<obert C:;1hn proposing a definition of an e11viro11m<:nlal <~thic: in 1\merica. 1\ Joumol forum follows. with fin: prominnnt e11viro1rnw11tal olJsefl'ers C1n swt:ring tlw question: lws the nthi c: tukn11 hold? l·: P1\ l\dministrnlur I.cc :VI. Tlwm;1s discusses wht:lhcr On Staten Island, Fresh Kills Landfill-the world's largest garbage dump-receives waste from all h;ivc /\1ll(:ric:an incl ivi duals five of New York City's boro ughs. Here a crane unloads waste from barges and loads it onto goll!:11 sc:rious about trucks for distribution elsewhere around the dump site. W illiam C. Franz photo, Staten Island Register. environnwntal prott:c.tion 11s a prn c. ti c:al m.ittc:r in thuir own li v1:s, and a subsnqucmt llroaclening the isst1e's this country up to the River in the nu tion's capital. article ;111alyws the find ings pt:rspective, Cro Hnrlem present: u box provides u On another environnwntal of rl!u:nt public opinion Brundtland. -

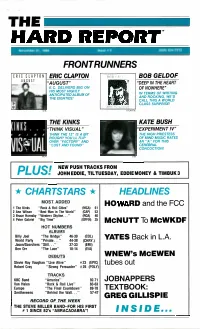

HARD REPORT' November 21, 1986 Issue # 6 (609) 654-7272 FRONTRUNNERS ERIC CLAPTON BOB GELDOF "AUGUST" "DEEP in the HEART E.C

THE HARD REPORT' November 21, 1986 Issue # 6 (609) 654-7272 FRONTRUNNERS ERIC CLAPTON BOB GELDOF "AUGUST" "DEEP IN THE HEART E.C. DELIVERS BIG ON OF NOWHERE" HIS MOST HIGHLY ANTICIPATED ALBUM OF IN TERMS OF WRITING AND ROCKING, WE'D THE EIGHTIES! CALL THIS A WORLD CLASS SURPRISE! ATLANTIC THE KINKS KATE BUSH NINNS . "THINK VISUAL" "EXPERIMENT IV" THINK THE 12" IS A BIT THE HIGH PRIESTESS ROUGH? YOU'LL FLIP OF MIND MUSIC RATES OVER "FACTORY" AND AN "A" FOR THIS "LOST AND FOUND" CEREBRAL CONCOCTION! MCA EMI JN OE HWN PE UD SD Fs RD OA My PLUS! ETTRACKS EDDIE MONEY & TIMBUK3 CHARTSTARS * HEADLINES MOST ADDED HOWARD and the FCC 1 The Kinks "Rock & Roll Cities" (MCA) 61 2 Ann Wilson "Best Man in The World" (CAP) 53 3 Bruce Hornsby "Western Skyline..." (RCA) 40 4 Peter Gabriel "Big Time" (GEFFEN) 35 McNUTT To McWKDF HOT NUMBERS ALBUMS Billy Joel "The Bridge" 46-39 (COL) YATES Back in L.A. World Party "Private. 44-38 (CHRY.) Jason/Scorchers"Still..." 37-33 (EMI) Ben Orr "The Lace" 18-14 (E/A) DEBUTS WNEW's McEWEN Stevie Ray Vaughan "Live Alive" #23(EPIC) tubes out Robert Cray "Strong Persuader" #26 (POLY) TRACKS KBC Band "America" 92-71 JOBNAPPERS Van Halen "Rock & Roll Live" 83-63 Europe "The Final Countdown" 89-78 TEXTBOOK: Smithereens "Behind the Wall..." 57-47 GREG GILLISPIE RECORD OF THE WEEK THE STEVE MILLER BAND --FOR HIS FIRST # 1 SINCE 82's "ABRACADABRA"! INSIDE... %tea' &Mai& &Mal& EtiZiraZ CiairlZif:.-.ZaW. CfMCOLZ &L -Z Cad CcIZ Cad' Ca& &Yet Cif& Ca& Ca& Cge. -

Crossing the Floor Roy Douglas a Failure of Leadership Liberal Defections 1918–29 Senator Jerry Grafstein Winston Churchill As a Liberal J

Journal of Issue 25 / Winter 1999–2000 / £5.00 Liberal DemocratHISTORY Crossing the Floor Roy Douglas A Failure of Leadership Liberal Defections 1918–29 Senator Jerry Grafstein Winston Churchill as a Liberal J. Graham Jones A Breach in the Family Megan and Gwilym Lloyd George Nick Cott The Case of the Liberal Nationals A re-evaluation Robert Maclennan MP Breaking the Mould? The SDP Liberal Democrat History Group Issue 25: Winter 1999–2000 Journal of Liberal Democrat History Political Defections Special issue: Political Defections The Journal of Liberal Democrat History is published quarterly by the Liberal Democrat History Group 3 Crossing the floor ISSN 1463-6557 Graham Lippiatt Liberal Democrat History Group Editorial The Liberal Democrat History Group promotes the discussion and research of 5 Out from under the umbrella historical topics, particularly those relating to the histories of the Liberal Democrats, Liberal Tony Little Party and the SDP. The Group organises The defection of the Liberal Unionists discussion meetings and publishes the Journal and other occasional publications. 15 Winston Churchill as a Liberal For more information, including details of publications, back issues of the Journal, tape Senator Jerry S. Grafstein records of meetings and archive and other Churchill’s career in the Liberal Party research sources, see our web site: www.dbrack.dircon.co.uk/ldhg. 18 A failure of leadership Hon President: Earl Russell. Chair: Graham Lippiatt. Roy Douglas Liberal defections 1918–29 Editorial/Correspondence Contributions to the Journal – letters, 24 Tory cuckoos in the Liberal nest? articles, and book reviews – are invited. The Journal is a refereed publication; all articles Nick Cott submitted will be reviewed. -

Political Parties and Welfare Associations

Department of Sociology Umeå University Political parties and welfare associations by Ingrid Grosse Doctoral theses at the Department of Sociology Umeå University No 50 2007 Department of Sociology Umeå University Thesis 2007 Printed by Print & Media December 2007 Cover design: Gabriella Dekombis © Ingrid Grosse ISSN 1104-2508 ISBN 978-91-7264-478-6 Grosse, Ingrid. Political parties and welfare associations. Doctoral Dissertation in Sociology at the Faculty of Social Sciences, Umeå University, 2007. ISBN 978-91-7264-478-6 ISSN 1104-2508 ABSTRACT Scandinavian countries are usually assumed to be less disposed than other countries to involve associations as welfare producers. They are assumed to be so disinclined due to their strong statutory welfare involvement, which “crowds-out” associational welfare production; their ethnic, cultural and religious homogeneity, which leads to a lack of minority interests in associational welfare production; and to their strong working-class organisations, which are supposed to prefer statutory welfare solutions. These assumptions are questioned here, because they cannot account for salient associational welfare production in the welfare areas of housing and child-care in two Scandinavian countries, Sweden and Norway. In order to approach an explanation for the phenomena of associational welfare production in Sweden and Norway, some refinements of current theories are suggested. First, it is argued that welfare associations usually depend on statutory support in order to produce welfare on a salient level. Second, it is supposed that any form of particularistic interest in welfare production, not only ethnic, cultural or religious minority interests, can lead to associational welfare. With respect to these assumptions, this thesis supposes that political parties are organisations that, on one hand, influence statutory decisions regarding associational welfare production, and, on the other hand, pursue particularistic interests in associational welfare production. -

Download Publication

No. 43 Working Papers Working Negotiating Between Unequal Neighbours: India‘s Role in Nepal‘s Recent Constitution-Making Process Prakash Bhattarai December 2018 1 Negotiating Between Unequal Neighbours: India’s Role in Nepal’s Recent Constitution-Making Process1 Prakash Bhattarai ABSTRACT Nepal’s post-conflict constitution-making process has seen the involvement of many international actors. While studies on democracy promotion, to this day, mainly focus on Western “donors” and international organizations, this paper looks at the role played by India in the complicated process of moving from a peace agreement to the establishment of an inclusive, democratic constitution in Nepal. More specifically, it is analysed how a powerful neighbouring democracy (India) participated in what is essentially a domestic negotiation process (constitution-making) with a view to influencing the emerging demo- cratic regime. In terms of the issues on the negotiation table, the analysis shows that India, in pushing for an inclusive constitution, pursued the specific agenda of supporting the inclusion of the Madheshis, an ethnic group mostly living in Nepal’s Terai region. In terms of negotiation strategies, the paper identifies four different ways in which India tried to influence the constitution: high-level dialogue; economic blockade; international coalition building; and targeted support of domestic oppositional forces in Nepal. Com- prehensive as this negotiation strategy was, it only met with partial success. Parameters that limited India’s influence included the domestic strength and legitimacy of the official Nepali position (elite alignment; popular support) as well as scepticism concerning In- dia’s role in Nepal, which was reinforced by India’s overly partisan agenda. -

Nepal's Constitution (I): Evolution Not Revolution

NEPAL’S CONSTITUTION (I): EVOLUTION NOT REVOLUTION Asia Report N°233 – 27 August 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS ................................................. i I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................. 1 II. STEPPING OFF THE EDGE .......................................................................................... 3 A. FRUSTRATED IN FEDERALISM ...................................................................................................... 3 1. The sticking points ....................................................................................................................... 3 2. Bogeymen .................................................................................................................................... 5 3. Missing all the signs ..................................................................................................................... 6 4. The final weeks of the assembly .................................................................................................. 8 5. The mood outside Kathmandu ................................................................................................... 10 B. WHAT HAPPENED ON 27 MAY ................................................................................................... 12 1. Talks ........................................................................................................................................... 12 -

How to Choose a Political Party

FastFACTS How to Choose a Political Party When you sign up to vote, you can join a political party. A political party is a group of people who share the same ideas about how the government should be run and what it should do. They work together to win elections. You can also choose not to join any of the political parties and still be a voter. There is no cost to join a party. How to choose a political party: • Choose a political party that has the same general views you do. For example, some political parties think that government should No Party Preference do more for people. Others feel that government should make it If you do not want to register easier for people to do things for themselves. with a political party (you • If you do not want to join a political party, mark that box on your want to be “independent” voter registration form. This is called “no party preference.” Know of any political party), mark that if you do, you may have limited choices for party candidates in “I do not want to register Presidential primary elections. with a political party” on the registration form. In • You can change your political party registration at any time. Just fill California, you can still out a new voter registration form and check a different party box. vote for any candidate in The deadline to change your party is 15 days before the election. a primary election, except If you are not registered with a political party and for Presidential candidates. -

The Legislature

6 The Legislature Key Terms Ad hoc Committees (p. 241) Also known as a working legislative committee, whose mandate is time-limited. Adjournment (p. 235) The temporary suspension of a legislative sitting until it reconvenes. Auditor General (p. 228) An independent officer responsible for auditing and reporting to the legislature regarding a government’s spending and operations. Backbenchers (p. 225) Rank-and-file legislators without cabinet responsibilities or other special legislative titles or duties. Bicameral legislature (p. 208) A legislative body consisting of two chambers (or “houses”). Bill (p. 241) A piece of draft legislation tabled in the legislature. Budget (p. 236) A document containing the government’s projected revenue, expenditures, and economic forecasts. Budget Estimates (p. 237) The more detailed, line-by-line statements of how each department will treat revenues and expenditures. By-election (p. 208) A district-level election held between general elections. Coalition government (p. 219) A hung parliament in which the cabinet consists of members from more than one political party. Committee of the Whole (p. 241) Another name for the body of all legislators. Confidence convention (p. 208)The practice under which a government must relinquish power when it loses a critical legislative vote. Inside Canadian Politics © Oxford University Press Canada, 2016 Contempt (p. 224) A formal denunciation of a member’s or government’s unparliamentary behaviour by the speaker. Consensus Government (p. 247) A system of governance that operates without political parties. Crossing the floor (p. 216) A situation in which a member of the legislature leaves one political party to join another party.