Program Notes | Beethoven's Fifth with Eschenbach

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Season 2018-2019 the Philadelphia Orchestra

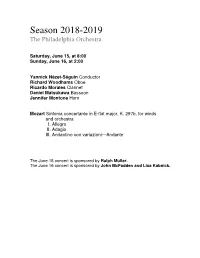

Season 2018-2019 The Philadelphia Orchestra Saturday, June 15, at 8:00 Sunday, June 16, at 2:00 Yannick Nézet-Séguin Conductor Richard Woodhams Oboe Ricardo Morales Clarinet Daniel Matsukawa Bassoon Jennifer Montone Horn Mozart Sinfonia concertante in E-flat major, K. 297b, for winds and orchestra I. Allegro II. Adagio III. Andantino con variazioni—Andante The June 15 concert is sponsored by Ralph Muller. The June 16 concert is sponsored by John McFadden and Lisa Kabnick. 24 The Philadelphia Orchestra Jessica Griffin The Philadelphia Orchestra Philadelphia is home and orchestra, and maximizes is one of the preeminent the Orchestra continues impact through Research. orchestras in the world, to discover new and The Orchestra’s award- renowned for its distinctive inventive ways to nurture winning Collaborative sound, desired for its its relationship with its Learning programs engage keen ability to capture the loyal patrons at its home over 50,000 students, hearts and imaginations of in the Kimmel Center, families, and community audiences, and admired for and also with those who members through programs a legacy of imagination and enjoy the Orchestra’s area such as PlayINs, side-by- innovation on and off the performances at the Mann sides, PopUP concerts, concert stage. The Orchestra Center, Penn’s Landing, free Neighborhood is inspiring the future and and other cultural, civic, Concerts, School Concerts, transforming its rich tradition and learning venues. The and residency work in of achievement, sustaining Orchestra maintains a Philadelphia and abroad. the highest level of artistic strong commitment to Through concerts, tours, quality, but also challenging— collaborations with cultural residencies, presentations, and exceeding—that level, and community organizations and recordings, the on a regional and national by creating powerful musical Orchestra is a global cultural level, all of which create experiences for audiences at ambassador for Philadelphia greater access and home and around the world. -

ARSC Journal

A Discography of the Choral Symphony by J. F. Weber In previous issues of this Journal (XV:2-3; XVI:l-2), an effort was made to compile parts of a composer discography in depth rather than breadth. This one started in a similar vein with the realization that SO CDs of the Beethoven Ninth Symphony had been released (the total is now over 701). This should have been no surprise, for writers have stated that the playing time of the CD was designed to accommodate this work. After eighteen months' effort, a reasonably complete discography of the work has emerged. The wonder is that it took so long to collect a body of information (especially the full names of the vocalists) that had already been published in various places at various times. The Japanese discographers had made a good start, and some of their data would have been difficult to find otherwise, but quite a few corrections and additions have been made and some recording dates have been obtained that seem to have remained 1.Dlpublished so far. The first point to notice is that six versions of the Ninth didn't appear on the expected single CD. Bl:lhm (118) and Solti (96) exceeded the 75 minutes generally assumed (until recently) to be the maximum CD playing time, but Walter (37), Kegel (126), Mehta (127), and Thomas (130) were not so burdened and have been reissued on single CDs since the first CD release. On the other hand, the rather short Leibowitz (76), Toscanini (11), and Busch (25) versions have recently been issued with fillers. -

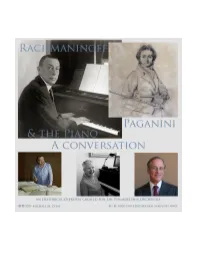

Rachmaninoff, Paganini, & the Piano; a Conversation

Rachmaninoff, Paganini, & the Piano; a Conversation Tracks and clips 1. Rachmaninoff in Paris 16:08 a. Niccolò Paganini, 24 Caprices for Solo Violin, Op. 1, Michael Rabin, EMI 724356799820, recorded 9/5/1958. b. Sergey Rachmaninoff (SR), Rapsodie sur un theme de Paganini, Op. 43, SR, Leopold Stokowski, Philadelphia Orchestra (PO), BMG Classics 09026-61658, recorded 12/24/1934 (PR). c. Fryderyk Franciszek Chopin (FC), Twelve Études, Op. 25, Alfred Cortot, Deutsche Grammophon Gesellschaft (DGG) 456751, recorded 7/1935. d. SR, Piano Concerto No. 3 in d, Op. 30, SR, Eugene Ormandy (EO), PO, Naxos 8.110601, recorded 12/4/1939.* e. Carl Maria von Weber, Rondo Brillante in E♭, J. 252, Julian Jabobson, Meridian CDE 84251, released 1993.† f. FC, Twelve Études, Op. 25, Ruth Slenczynska (RS), Musical Heritage Society MHS 3798, released 1978. g. SR, Preludes, Op. 32, RS, Ivory Classics 64405-70902, recorded 4/8/1984. h. Georges Enesco, Cello & Piano Sonata, Op. 26 No. 2, Alexandre Dmitriev, Alexandre Paley, Saphir Productions LVC1170, released 10/29/2012.† i. Claude Deubssy, Children’s Corner Suite, L. 113, Walter Gieseking, Dante 167, recorded 1937. j. Ibid., but SR, Victor B-24193, recorded 4/2/1921, TvJ35-zZa-I. ‡ k. SR, Piano Concerto No. 3 in d, Op. 30, Walter Gieseking, John Barbirolli, Philharmonic-Symphony Orchestra, Music & Arts MACD 1095, recorded 2/1939.† l. SR, Preludes, Op. 23, RS, Ivory Classics 64405-70902, recorded 4/8/1984. 2. Rachmaninoff & Paganini 6:08 a. Niccolò Paganini, op. cit. b. PR. c. Arcangelo Corelli, Violin Sonata in d, Op. 5 No. 12, Pavlo Beznosiuk, Linn CKD 412, recorded 1/11/2012.♢ d. -

[email protected] CHRISTOPH ESCHENBACH to CO

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE March 7, 2018 Contact: Katherine E. Johnson (212) 875-5700; [email protected] CHRISTOPH ESCHENBACH TO CONDUCT THE NEW YORK PHILHARMONIC MOZART’s Piano Concerto No. 22 with TILL FELLNER in His Philharmonic Debut BRUCKNER’s Symphony No. 9 April 19, 21, and 24, 2018 Christoph Eschenbach will conduct the New York Philharmonic in a program of works by Austrian composers: Mozart’s Piano Concerto No. 22, with Austrian pianist Till Fellner as soloist in his Philharmonic debut, and Bruckner’s Symphony No. 9 (Ed. Nowak), Thursday, April 19, 2018, at 7:30 p.m.; Saturday, April 21 at 8:00 p.m.; and Tuesday, April 24 at 7:30 p.m. German conductor Christoph Eschenbach began his career as a pianist, making his New York Philharmonic debut as piano soloist in Mozart’s Piano Concerto No. 24 in 1974. Both Christoph Eschenbach and Till Fellner won the Clara Haskil International Piano Competition, in 1965 and 1993, respectively. Mr. Fellner subsequently recorded Mozart’s Piano Concerto No. 22 on the Claves label in collaboration with the Clara Haskil Competition. The New York Times wrote of Mr. Eschenbach’s conducting Bruckner’s Symphony No. 9 with the New York Philharmonic in 2008: “Mr. Eschenbach, a compelling Bruckner interpreter, brought a sense of structure and proportion to the music without diminishing the qualities of humility and awe that make it so gripping. … the orchestra responded with playing of striking power and commitment.” Artists Christoph Eschenbach is in demand as a distinguished guest conductor with the finest orchestras and opera houses throughout the world, including those in Vienna, Berlin, Paris, London, New York, Boston, Chicago, Los Angeles, Milan, Rome, Munich, Dresden, Leipzig, Madrid, Tokyo, and Shanghai. -

[email protected] N

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE UPDATED May 28, 2015 February 17, 2015 Contact: Katherine E. Johnson (212) 875-5718; [email protected] NEW YORK PHILHARMONIC TO RETURN TO BRAVO! VAIL FOR 13th-ANNUAL SUMMER RESIDENCY, JULY 24–31, 2015 Music Director Alan Gilbert To Lead Three Programs Bramwell Tovey and Joshua Weilerstein Also To Conduct Soloists To Include Violinist Midori, Cellist Alisa Weilerstein, Pianists Jon Kimura Parker and Anne-Marie McDermott, Acting Concertmaster Sheryl Staples, Principal Viola Cynthia Phelps, Soprano Julia Bullock, and Tenor Ben Bliss New York Philharmonic Musicians To Perform Chamber Concert The New York Philharmonic will return to Bravo! Vail in Colorado for the Orchestra’s 13th- annual summer residency there, featuring six concerts July 24–31, 2015, as well as a chamber music concert performed by Philharmonic musicians. Music Director Alan Gilbert will conduct three programs, July 29–31, including an all-American program and works by Mendelssohn, Mahler, Mozart, and Shostakovich. The other Philharmonic concerts, conducted by Bramwell Tovey (July 24 and 26) and former New York Philharmonic Assistant Conductor Joshua Weilerstein (July 25), will feature works by Grieg, Elgar, Tchaikovsky, Rachmaninoff, and Richard Strauss, among others. The soloists appearing during the Orchestra’s residency are pianists Jon Kimura Parker and Anne-Marie McDermott, cellist Alisa Weilerstein, violinist Midori, soprano Julia Bullock and tenor Ben Bliss, and Acting Concertmaster Sheryl Staples and Principal Viola Cynthia Phelps. The New York Philharmonic has performed at Bravo! Vail each summer since 2003. Alan Gilbert will lead the concert on Wednesday, July 29, featuring Mendelssohn’s Violin Concerto, with Midori as soloist, and Mahler’s Symphony No. -

Lynn Harrell 59 Olivier Latry

Table of Contents | Week 19 7 bso news 15 on display in symphony hall 16 the boston symphony orchestra 19 completing the circle: wagner’s brave new world in the concert hall by thomas may 25 this week’s program Notes on the Program 26 The Program in Brief… 27 Wolfgang Amadè Mozart 35 Augusta Read Thomas 43 Camille Saint-Saëns 51 To Read and Hear More… Guest Artists 55 Christoph Eschenbach 57 Lynn Harrell 59 Olivier Latry 62 sponsors and donors 72 future programs 74 symphony hall exit plan 75 symphony hall information program copyright ©2013 Boston Symphony Orchestra, Inc. design by Hecht Design, Arlington, MA cover photo of BSO cellist Alexandre Lecarme by Stu Rosner BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA Symphony Hall, 301 Massachusetts Avenue Boston, MA 02115-4511 (617)266-1492 bso.org bernard haitink, lacroix family fund conductor emeritus, endowed in perpetuity seiji ozawa, music director laureate 132nd season, 2012–2013 trustees of the boston symphony orchestra, inc. Edmund Kelly, Chairman • Paul Buttenwieser, Vice-Chairman • Diddy Cullinane, Vice-Chairman • Stephen B. Kay, Vice-Chairman • Robert P. O’Block, Vice-Chairman • Roger T. Servison, Vice-Chairman • Stephen R. Weber, Vice-Chairman • Theresa M. Stone, Treasurer William F. Achtmeyer • George D. Behrakis • Jan Brett • Susan Bredhoff Cohen, ex-officio • Richard F. Connolly, Jr. • Cynthia Curme • Alan J. Dworsky • William R. Elfers • Thomas E. Faust, Jr. • Nancy J. Fitzpatrick • Michael Gordon • Brent L. Henry • Charles W. Jack, ex-officio • Charles H. Jenkins, Jr. • Joyce G. Linde • John M. Loder • Nancy K. Lubin • Carmine A. Martignetti • Robert J. Mayer, M.D. • Susan W. -

Mercredi 25 Avril 2012 Nora Gubisch | Ensemble Intercontemporain | Alain Altinoglu

Roch-Olivier Maistre, Président du Conseil d’administration Laurent Bayle, Directeur général Mercredi 25 avril 2012 avril 25 Mercredi | Mercredi 25 avril 2012 Nora Gubisch | Ensemble intercontemporain | Alain Altinoglu Vous avez la possibilité de consulter les notes de programme en ligne, 2 jours avant chaque concert, à l’adresse suivante : www.citedelamusique.fr Altinoglu | Alain Gubisch | Ensemble intercontemporain Nora 2 MERCREDI 25 AVRIL – 20H Salle des concerts Lu Wang Siren Song Igor Stravinski Huit Miniatures instrumentales Concertino pour douze instruments Maurice Ravel Trois Poèmes de Stéphane Mallarmé entracte Marc-André Dalbavie Palimpseste Luciano Berio Folk Songs Nora Gubisch, mezzo-soprano Ensemble intercontemporain Alain Altinoglu, direction Diffusé en direct sur les sites Internet www.citedelamusiquelive.tv et www.arteliveweb.com, ce concert restera disponible gratuitement pendant trois mois. Il est également retransmis en direct sur France Musique. Coproduction Cité de la musique, Ensemble intercontemporain. Fin du concert vers 22h15. 3 Lu Wang (1982) Siren Song Composition : 2008. Création : 5 avril 2008 à New York, Merkin Concert Hall, par l’International Contemporary Ensemble (ICE), sous la direction de Matt Ward. Effectif : flûte / flûte piccolo, clarinette en si bémol / clarinette en mi bémol / clarinette basse – cor, trompette – piano – harpe – percussions – violon, alto, violoncelle. Éditeur : inédit. Durée : environ 7 minutes. Cette pièce peut être vue comme un court opéra. Elle utilise la translittération d’un ancien dialecte de Xi’an, ma ville natale, extrêmement puissant et musical qui, dans le parlé/chanté, se déploie en intervalles démesurés et en glissandi. J’avais été particulièrement fascinée par une voix que j’entendis chez un conteur qui chantait dans ce dialecte : c’était la voix sèche, comme affolée et pourtant très séduisante d’un vieil eunuque. -

Orchestre De Paris Asume El Papel De Asesor Artístico En 2020/2021 Y Será Su Próximo Director Musical a Partir De Septiembre De 2022

70 Festival de Granada Biografías Klaus Mäkelä Klaus Mäkelä es director principal y asesor artístico de la Filarmónica de Oslo. Con la Orchestre de Paris asume el papel de asesor artístico en 2020/2021 y será su próximo director musical a partir de septiembre de 2022. Es, además, director invitado principal de la Orquesta Sinfónica de la Radio Sueca y director artístico del Festival de Música de Turku. Como artista exclusivo de Decca Classics, Klaus Mäkelä ha grabado el ciclo completo de sinfonías de Sibelius con la Filarmónica de Oslo como primer proyecto con el sello, que será editado en la primavera de 2022. Klaus Mäkelä inaugura la temporada 2021/2022 de la Filarmónica de Oslo este mes de agosto con un concierto especial interpretando el Divertimento de Bartók, el Concierto para piano nº 1 con Yuja Wang como solista, dos obras de estreno del compositor noruego Mette Henriette y Lemminkäinen de Sibelius. Ofrecerá un repertorio de similar amplitud durante su segunda temporada en Oslo., incluyendo las grandes obras corales de J. S Bach, Mozart y William Walton, la Sinfonía nº 3 de Mahler y las nº 10 y 14 de Shostakóvich con los solistas Mika Kares y Asmik Grigorian. Entre las obras contemporáneas y de estreno se incluyen composiciones de Sally Beamish, Unsuk Chin, Jimmy Lopez, Andrew Norman y Kaija Saariaho. En la primavera de 2022, Klaus Mäkelä y la Filarmónica de Oslo interpretarán las sinfonías completas de Sibelius en la Wiener Konzerthaus y la Elbphilharmonie de Hamburgo, y en gira por Francia y el Reino Unido. Con la Orchestre de Paris, visitará los festivales de verano de Granada y Aix-en- Provence. -

An Interview with Robert Shaw: Reflections at Eighty

An Interview with Robert Shaw: Reflections at Eighty by Jeffrey Baxter RobertShaw .Robert Shaw's distinguished career began in New York City In 1979, Shaw was appointed by President Jimmy Carter to in 1938, where he prepared choruses for such renowned con the National Council on the Arts and he was a 1991 recipient of ductors as Fred Waring, Arturo Toscanini, and Bruno Walter. the Kennedy Center Honors, the nation's highest award given to In 1949 he formed the Robert Shaw Chorale, which for two artists. Musical America, the international directory of the per decades reigned as America's premier touring choir. Under the forming arts, named him Musician of the Year for 1992, and auspices ofthe U.S. State Department, the Chorale performed during the same year he was awarded the National Medal ofthe in thirty countries throughout Europe, the Soviet Union, the Arts in a White House ceremony. He was the 1993 recipient of Middle East, and Latin America. During this period Shaw also the Conductors' Guild TheodoreThomas Award, in recognition served as Music Director ofthe San Diego Symphony and then ofhis outstanding achievement in conducting and his contribu as Associate Conductor of the Cleveland Orchestra, working tions to the education and training ofyoung conductors. closely with George Szell for eleven years. He served as Music A regular guest conductor ofmajor orchestras in this country Director of the Atlanta Symphony Orchestra from 1967 to and abroad, Shaw also is in demand as a teacher and lecturer at 1988, during which time the orchestra garnered widespread leading U.S. -

2020-21 Season Brochure

2020 SEA- This year. This season. This orchestra. This music director. Our This performance. This artist. World This moment. This breath. This breath. 2021 SON This breath. Don’t blink. ThePhiladelphiaOrchestra MUSIC DIRECTOR YANNICK NÉZET-SÉGUIN our world Ours is a world divided. And yet, night after night, live music brings audiences together, gifting them with a shared experience. This season, Music Director Yannick Nézet-Séguin and The Philadelphia Orchestra invite you to experience the transformative power of fellowship through a bold exploration of sound. 2 2020–21 Season 3 “For me, music is more than an art form. It’s an artistic force connecting us to each other and to the world around us. I love that our concerts create a space for people to gather as a community—to explore and experience an incredible spectrum of music. Sometimes, we spend an evening in the concert hall together, and it’s simply some hours of joy and beauty. Other times there may be an additional purpose, music in dialogue with an issue or an idea, maybe historic or current, or even a thought that is still not fully formed in our minds and hearts. What’s wonderful is that music gives voice to ideas and feelings that words alone do not; it touches all aspects of our being. Music inspires us to reflect deeply, and music brings us great joy, and so much more. In the end, music connects us more deeply to Our World NOW.” —Yannick Nézet-Séguin 4 2020–21 Season 5 philorch.org / 215.893.1955 6A Thursday Yannick Leads Return to Brahms and Ravel Favorites the Academy Garrick Ohlsson Thursday, October 1 / 7:30 PM Thursday, January 21 / 7:30 PM Thursday, March 25 / 7:30 PM Academy of Music, Philadelphia Yannick Nézet-Séguin Conductor Michael Tilson Thomas Conductor Lisa Batiashvili Violin Yannick Nézet-Séguin Conductor Garrick Ohlsson Piano Hai-Ye Ni Cello Westminster Symphonic Choir Ravel Le Tombeau de Couperin Joe Miller Director Szymanowski Violin Concerto No. -

An Analysis of Honegger's Cello Concerto

AN ANALYSIS OF HONEGGER’S CELLO CONCERTO (1929): A RETURN TO SIMPLICITY? Denika Lam Kleinmann, B.M., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2014 APPROVED: Eugene Osadchy, Major Professor Clay Couturiaux, Minor Professor David Schwarz, Committee Member Daniel Arthurs, Committee Member John Holt, Chair of the Division of Instrumental Studies James Scott, Dean of the School of Music Mark Wardell, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Kleinmann, Denika Lam. An Analysis of Honegger’s Cello Concerto (1929): A Return to Simplicity? Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), May 2014, 58 pp., 3 tables, 28 examples, 33 references, 15 titles. Literature available on Honegger’s Cello Concerto suggests this concerto is often considered as a composition that resonates with Les Six traditions. While reflecting currents of Les Six, the Cello Concerto also features departures from Erik Satie’s and Jean Cocteau’s ideal for French composers to return to simplicity. Both characteristics of and departures from Les Six examined in this concerto include metric organization, thematic and rhythmic development, melodic wedge shapes, contrapuntal techniques, simplicity in orchestration, diatonicism, the use of humor, jazz influences, and other unique performance techniques. Copyright 2014 by Denika Lam Kleinmann ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF TABLES………………………………………………………………………………..iv LIST OF MUSICAL EXAMPLES………………………………………………………………..v CHAPTER I: INTRODUCTION………..………………………………………………………...1 CHAPTER II: HONEGGER’S -

2017-2018 Senior Recital-Elizabeth Lee (Cello)

Welcome to the 2017-2018 season. The talented students and Elizabeth Lee, Cello extraordinary faculty of the Lynn Conservatory of Music take this Bachelor of Music Recital Program opportunity to share with you the Sheng-Yuan Kuan beautiful world of music. Your ongoing support ensures our place Tuesday, April 24, 2018 at 5:30 p.m. among the premier conservatories of the world and a staple of our Amarnick-Goldstein Concert Hall community. Boca Raton, Florida - Jon Robertson, dean There are a number of ways by which you can help us fulfill our mission: Chant du Ménestrel Op. 71 Alexander Glazunov Friends of the Conservatory of Music (1865-1936) Lynn University’s Friends of the Conservatory of Music is a volunteer organization that supports high-quality music education through fundraising and community outreach. Raising more than $2 million since 2003, the Friends support Lynn’s effort to provide free tuition scholarships and room and board to all Conservatory of Music students. The group also raises money for the Dean’s Discretionary Fund, which supports the immediate needs of the Suite Italienne for Cello and Piano Igor Stravinsky university’s music performance students. This is accomplished (arr. Gregor Piatigorsky) (1882-1971) through annual gifts and special events, such as outreach concerts and the annual Gingerbread Holiday Concert. I. Introduzione To learn more about joining the Friends and its many benefits, II. Serenata such as complimentary concert admission, visit III. Aria Give.lynn.edu/support-music. IV.Tarantella The Leadership Society of Lynn University V. Minuetto e Finale The Leadership Society is the premier annual giving society for donors who are committed to ensuring a standard of excellence at Lynn for all students.