The Management of Tics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ADHD Parents Medication Guide Revised July 2013

ADHD Parents Medication Guide Revised July 2013 Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder Prepared by: American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry and American Psychiatric Association Supported by the Elaine Schlosser Lewis Fund Physician: ___________________________________________________ Address: ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ Phone: ___________________________________________________ Email: ___________________________________________________ ADHD Parents Medication Guide – July 2013 2 Introduction Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) is a neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by difficulty paying attention, excessive activity, and impulsivity (acting before you think). ADHD is usually identified when children are in grade school but can be diagnosed at any time from preschool to adulthood. Recent studies indicate that almost 10 percent of children between the ages of 4 to 17 are reported by their parents as being diagnosed with ADHD. So in a classroom of 30 children, two to three children may have ADHD.1,2,3,4,5 Short attention spans and high levels of activity are a normal part of childhood. For children with ADHD, these behaviors are excessive, inappropriate for their age, and interfere with daily functioning at home, school, and with peers. Some children with ADHD only have problems with attention; other children only have issues with hyperactivity and impulsivity; most children with ADHD have problems with all three. As they grow into adolescence and young adulthood, children with ADHD may become less hyperactive yet continue to have significant problems with distraction, disorganization, and poor impulse control. ADHD can interfere with a child’s ability to perform in school, do homework, follow rules, and develop and maintain peer relationships. When children become adolescents, ADHD can increase their risk of dropping out of school or having disciplinary problems. -

Reveiw Week 3 Final with Questions

REVIEW 3 SOMATIZATION AND RELATED DISORDERS SOMATIZATION AND RELATED DISORDERS SOMATIZATION ▸ Psychological problems or concerns that are converted into and communicated as physical distress ▸ Anxiety is either Conscious or Unconscious ▸ Physical Illness is Real SOMATIZATION AND RELATED DISORDERS - SSD SOMATIC SYMPTOM DISORDER A. One or more somatic symptoms that are distressing or result in significant disruption of daily life B. Excessive thoughts, feelings, or behaviors related to the somatic symptoms or associated health concerns as manifested by at least one of the following 1. Disproportionate and persistent thoughts about the seriousness or one’s symptoms 2. Persistently high level of anxiety about health or symptoms 3. Excessive time and energy devoted to these symptoms or health concerns C. Although any one somatic symptom may not be continuously present, the state of being symptomatic is persistent (typically more than 6 months) SOMATIZATION AND RELATED DISORDERS - SSD TREATMENT ▸ Regular office visits with the same physician ▸ Psychotherapy ▸ Validate the patient’s feelings/experience of symptoms SOMATIZATION AND RELATED DISORDERS - ILLNESS ANXIETY DISORDER ILLNESS ANXIETY DISORDER A. Formerly hypochondriasis B. Preoccupation with having or acquiring a serious illness C. Somatic symptoms are not present or, if present, are only mild in intensity. If another medical condition is present or there is a high risk for developing a medical condition (strong FH), the preoccupation is clearly excessive or disproportionate D. There is a high level of anxiety about health, and the individual is easily alarmed about personal health status (preoccupation with idea one is sick) E. The individual performs excessive health-related behaviors (checking body) or exhibits maladaptive avoidance (avoids doctors) F. -

Guanfacine Extended Release for ADHD

Out of the Pipeline p Guanfacine extended release for ADHD Floyd R. Sallee, MD, PhD uanfacine extended release (GXR)— Table 1 α Once-daily a selective -2 adrenergic agonist Guanfacine extended release: GFDA-approved for the treatment formulation may of attention-defi cit/hyperactivity disor- Fast facts improve adherence der (ADHD)—has demonstrated effi cacy Brand name: Intuniv and control for inattentive and hyperactive/impulsive Indication: Attention-defi cit/hyperactivity symptoms across disorder symptom domains in 2 large trials lasting® Dowden Health Media a full day 8 and 9 weeks.1,2 GXR’s once-daily formu- Approval date: September 3, 2009 lation may increase adherence and deliver Availability date: November 2009 consistent control of symptomsCopyright across a For personalManufacturer: use Shire only full day (Table 1). Dosing forms: 1-mg, 2-mg, 3-mg, and 4-mg extended-release tablets Recommended dosage: 0.05 to 0.12 mg/kg Clinical implications once daily GXR exhibits enhancement of noradren- ergic pathways through selective direct receptor action in the prefrontal cortex.3 brain believed to play a major role in at- This mechanism of action is different from tentional and organizational functions that that of other FDA-approved ADHD medi- preclinical research has linked to ADHD.3 cations. GXR can be used alone or in com- The postsynaptic α-2A receptor is bination with stimulants or atomoxetine thought to play a central role in the opti- for treating complex ADHD, such as cases mal functioning of the PFC as illustrated accompanied by oppositional features and by the “inverted U hypothesis of PFC ac- emotional dysregulation or characterized tivation.”4 In this model, cyclic adenos- by partial stimulant response. -

Neurobiology of the Premonitory Urge in Tourette Syndrome: Pathophysiology and Treatment Implications

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE HHS Public Access provided by Aston Publications Explorer Author manuscript Author ManuscriptAuthor Manuscript Author J Neuropsychiatry Manuscript Author Clin Neurosci Manuscript Author . Author manuscript; available in PMC 2017 April 28. Published in final edited form as: J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2017 ; 29(2): 95–104. doi:10.1176/appi.neuropsych.16070141. Neurobiology of the premonitory urge in Tourette syndrome: Pathophysiology and treatment implications Andrea E. Cavanna1,2,3,*, Kevin J Black4, Mark Hallett5, and Valerie Voon6,7,8 1Department of Neuropsychiatry Research Group, BSMHFT and University of Birmingham, Birmingham, UK 2School of Life and Health Sciences, Aston University, Birmingham, UK 3University College London and Institute of Neurology, London, UK 4Departments of Psychiatry, Neurology, Radiology, and Anatomy & Neuroscience, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, MO, USA 5Human Motor Control Section, Medical Neurology Branch, National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA 6Department of Psychiatry, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK 7Behavioural and Clinical Neurosciences Institute, Cambridge, UK 8Cambridgeshire and Peterborough NHS Foundation Trust, Cambridge, UK Abstract Motor and vocal tics are relatively common motor manifestations identified as the core features of Tourette syndrome. Although traditional descriptions have focused on objective phenomenological -

Final Program

FINAL PROGRAM 2nd Pan American Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders Congress JUNE 22-24, 2018 MIAMI, FLORIDA, USA www.pascongress2018.org Table of Contents About MDS ...............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................2 About MDS-PAS Section ...........................................................................................................................................................................................................................3 Continuing Medical Education (CME) Information ....................................................................................................................................................................................4 Hilton Miami Downtown Floor Plan .........................................................................................................................................................................................................4 Schedule-At-A-Glance .............................................................................................................................................................................................................................5 Session Definitions ...................................................................................................................................................................................................................................6 -

TC Newsletter – June Edition

JUNE 4, 2018 National Newsletter June 2018 NATIONAL EVENTS TS Edmonton 10 Things You Didn’t other people’s rights (e.g., Family being aggressive, bullying, Event - Know About Tourette damaging property on Sunday Syndrome purpose, stealing, breaking June 10th serious rules). Conduct Bronx Bowl 12940-127 St. 1. Only 10% of the disorder, according to this West, Edmonton, AB people with TS have no study, can occur in people with other associated TS but this is related to the Winnipeg disorders. This is called presence of ADHD and a family Chapter pure-TS or TS-only. history of aggressive and Event - violent behaviour. Picnic in the Park 2. Though rare, some people with TS have a palatal tic. June 10th This tic involves the soft palate moving 8. Depression, which is Assinboine Park Winnipeg, common among people with while simultaneously hearing a clicking sound. Manitoba TS, is a lifetime risk for 10% of FREE to Attend -but RSVP 3. While TS is genetic and occurs across all cultures, people with TS. Depending on REQUIRED by: June 6, 2018 some differences have been noted between cultures with the study, between 2-9% of RSVP via EMAIL to: regard to certain accompanying conditions like anxiety, people with TS have [email protected] include # of people depression, LD, impulse control, aggression, ODD, and depression. attending. conduct disorder. 9. Some people with TS can have retching or vomiting tics. Shine a Light on Tourette 4. Coprolalia (socially inappropriate language) and Syndrome- copropraxia (socially inappropriate movement or Niagara Falls gestures) are not unique to Tourette Syndrome. -

Tourrete-Syndrome.Pdf

ISSN : 2376-0249 International Journal of Volume 2 • Issue 8• 1000360 Clinical & Medical Imaging August, 2015 http://dx.doi.org/10.4172/2376-0249.1000360 Case Blog Title: Tourrete Syndrome Rajarshi Sannigrahi1, Ajay Manickam1*, Shaswati Sengupta1, Jayanta saha1, SK Basu1 and Sunetra Mondal2 1Department of ENT and Head Neck Surgery, RG Kar Medical College and Hospital, Kolkata, India 2Vivekananda institute of medical science. Kolkata India Introduction Tourette syndrome is an inherited neuropsychiatric disorder with onset in childhood; it is characterized by multiple motor tics and at least one vocal tic. The occurrence of tics wax and wane with time can be suppressed voluntarily and are frequently preceded by a premonitory urge. Tourette is defined as a part of spectrum of tic disorders which include provisional, transient or persistent tics. The prevalence of tourrete is 0.4% to 3.8% among children between 5 to 18 years [1]. The tourette syndrome can be associated with use of obscene words and derogatory remarks but this is present in only a few cases [2]. Eye blinking, coughing, throat clearing, sniffing and facial movements are the common type of tics. Tourrete does not affect intelligence or life expectancy. To urrete is often associated with comorbid condition such as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and obsessive compulsive disorder(OCD). These conditions often cause more functional impairment than the tics. Case Study 6 year old female patient presented in the ENT opd with recurrent sore throat. On examination bilateral tonsillitis was seen. During examination frequent blinking of eyes, grimacing, frowning and frequent protrusion of tongue was observed. -

Coordinator Toolkit 2017

COORDINATOR TOOLKIT 2017 2 Table of Contents 4 A Word from the Chair 5 Your Support Network 6 Introduction to the Trek 7 Talking Points 8 What is the Trek? 9 Trek kick off 10 The Starting Line and Beyond 12 Volunteer Engagement 14 Promotion 18 Prizes and Giveaways 21 Online Giving Software – Making a donation 27 Online Giving Software – Registering to Trek 32 Administration 33 Incentives for affiliates 34 Operational Budget & Shipments 35 Event Execution 36 Coordinator Supply Checklist 37 Suggested Planning Timelines 38 Suggestions to grow your Trek 39 Tourette Canada Fact Sheet 40 Master Item Checklist 41 Planning Checklists 48 My Notes 3 Additional info (available on www.tourette.ca) Question & Answer Flyer Pledge Form Waiver and Release (English & French) Media Release – National Kick Off Online Giving Software – How to make a donation Online Giving Software – Registering to Trek Additional info (available on Dropbox) Donation Letter Template (English & French) In Kind letter Request Sponsorship Request Letter Template General Introduction Letter Media Release – Local Trek How to hold a school Trek Sponsor Thank you letter Trek Letterhead Trek Logos, digital banners (English & French) Tourette Canada Expense Form Template Radio Stations & Newspapers List (By Community) Coordinator files for meetings, minutes, agenda, logistics, etc 4 A Message of Thanks For 40 years, Tourette Canada has been dedicated to improving the lives of Canadians living with Tourette Syndrome (TS) and its associated disorders. Our organization relies on the generosity of the community to support our ongoing efforts to realize our Vision – to achieve an empowered Tourette community in an inclusive Canada. -

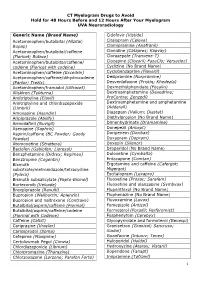

CT Myelogram Drugs to Avoid Hold for 48 Hours Before and 12 Hours After Your Myelogram UVA Neuroradiology

CT Myelogram Drugs to Avoid Hold for 48 Hours Before and 12 Hours After Your Myelogram UVA Neuroradiology Generic Name (Brand Name) Cidofovir (Vistide) Acetaminophen/butalbital (Allzital; Citalopram (Celexa) Bupap) Clomipramine (Anafranil) Acetaminophen/butalbital/caffeine Clonidine (Catapres; Kapvay) (Fioricet; Butace) Clorazepate (Tranxene-T) Acetaminophen/butalbital/caffeine/ Clozapine (Clozaril; FazaClo; Versacloz) codeine (Fioricet with codeine) Cyclizine (No Brand Name) Acetaminophen/caffeine (Excedrin) Cyclobenzaprine (Flexeril) Acetaminophen/caffeine/dihydrocodeine Desipramine (Norpramine) (Panlor; Trezix) Desvenlafaxine (Pristiq; Khedezla) Acetaminophen/tramadol (Ultracet) Dexmethylphenidate (Focalin) Aliskiren (Tekturna) Dextroamphetamine (Dexedrine; Amitriptyline (Elavil) ProCentra; Zenzedi) Amitriptyline and chlordiazepoxide Dextroamphetamine and amphetamine (Limbril) (Adderall) Amoxapine (Asendin) Diazepam (Valium; Diastat) Aripiprazole (Abilify) Diethylpropion (No Brand Name) Armodafinil (Nuvigil) Dimenhydrinate (Dramamine) Asenapine (Saphris) Donepezil (Aricept) Aspirin/caffeine (BC Powder; Goody Doripenem (Doribax) Powder) Doxapram (Dopram) Atomoxetine (Strattera) Doxepin (Silenor) Baclofen (Gablofen; Lioresal) Droperidol (No Brand Name) Benzphetamine (Didrex; Regimex) Duloxetine (Cymbalta) Benztropine (Cogentin) Entacapone (Comtan) Bismuth Ergotamine and caffeine (Cafergot; subcitrate/metronidazole/tetracycline Migergot) (Pylera) Escitalopram (Lexapro) Bismuth subsalicylate (Pepto-Bismol) Fluoxetine (Prozac; Sarafem) -

Tourette's Syndrome

Tourette’s Syndrome CHRISTOPHER KENNEY, MD; SHENG-HAN KUO, MD; and JOOHI JIMENEZ-SHAHED, MD Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, Texas Tourette’s syndrome is a movement disorder most commonly seen in school-age children. The incidence peaks around preadolescence with one half of cases resolving in early adult- hood. Tourette’s syndrome is the most common cause of tics, which are involuntary or semi- voluntary, sudden, brief, intermittent, repetitive movements (motor tics) or sounds (phonic tics). It is often associated with psychiatric comorbidities, mainly attention-deficit/hyperac- tivity disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder. Given its diverse presentation, Tourette’s syndrome can mimic many hyperkinetic disorders, making the diagnosis challenging at times. The etiology of this syndrome is thought to be related to basal ganglia dysfunction. Treatment can be behavioral, pharmacologic, or surgical, and is dictated by the most incapacitating symp- toms. Alpha2-adrenergic agonists are the first line of pharmacologic therapy, but dopamine- receptor–blocking drugs are required for multiple, complex tics. Dopamine-receptor–blocking drugs are associated with potential side effects including sedation, weight gain, acute dystonic reactions, and tardive dyskinesia. Appropriate diagnosis and treatment can substantially improve quality of life and psychosocial functioning in affected children. (Am Fam Physician. 2008;77(5):651-658, 659-660. Copyright © 2008 American Academy of Family Physicians.) ▲ Patient information: n 1885, Georges Gilles de la Tourette normal context or in inappropriate situa- A handout on Tourette’s described the major clinical features tions, thus calling attention to the person syndrome, written by the authors of this article, is of the syndrome that now carries his because of their exaggerated, forceful, and provided on p. -

Guideline for Preoperative Medication Management

Guideline: Preoperative Medication Management Guideline for Preoperative Medication Management Purpose of Guideline: To provide guidance to physicians, advanced practice providers (APPs), pharmacists, and nurses regarding medication management in the preoperative setting. Background: Appropriate perioperative medication management is essential to ensure positive surgical outcomes and prevent medication misadventures.1 Results from a prospective analysis of 1,025 patients admitted to a general surgical unit concluded that patients on at least one medication for a chronic disease are 2.7 times more likely to experience surgical complications compared with those not taking any medications. As the aging population requires more medication use and the availability of various nonprescription medications continues to increase, so does the risk of polypharmacy and the need for perioperative medication guidance.2 There are no well-designed trials to support evidence-based recommendations for perioperative medication management; however, general principles and best practice approaches are available. General considerations for perioperative medication management include a thorough medication history, understanding of the medication pharmacokinetics and potential for withdrawal symptoms, understanding the risks associated with the surgical procedure and the risks of medication discontinuation based on the intended indication. Clinical judgement must be exercised, especially if medication pharmacokinetics are not predictable or there are significant risks associated with inappropriate medication withdrawal (eg, tolerance) or continuation (eg, postsurgical infection).2 Clinical Assessment: Prior to instructing the patient on preoperative medication management, completion of a thorough medication history is recommended – including all information on prescription medications, over-the-counter medications, “as needed” medications, vitamins, supplements, and herbal medications. Allergies should also be verified and documented. -

Parent's Guide to Cbit

Basic Concepts of CBIT - Comprehensive Behavior Intervention for Tics By Steve Pally Volunteer Administrator, Tourette Canada Information & Support Forum www.TouretteSyndrome.ca www.Tourette.ca Volunteer Moderator, Tourettes Action Information & Support Forum http://forum.tourettes-action.org.uk/ www.tourettes-action.org.uk/ Providing Tools For Life CBIT (pronounced see-bit) combines six strategic therapeutic components in the form of a clinically proven comprehensive non-medication therapy to help a child (person) with Tourette Syndrome manage their tics. Behavioral Therapy Behavioral therapy is a treatment that teaches people with TS ways to manage their tics. Behavioral therapy is not a cure for tics. However, it can help reduce the number of tics, the severity of tics, the impact of tics, or a combination of all of these. It is important to understand that even though behavioral therapies might help reduce the severity of tics, this does not mean that tics are just psychological or that anyone with tics should be able to control them.2 Habit Reversal Habit reversal is one of the most studied behavioral interventions for people with tics1. It has two main parts: awareness training and competing response training. In the awareness training part, people identify each tic out loud. In the competing response part, people learn to do a new behavior that cannot happen at the same time as the tic. For example, if the person with TS has a tic that involves head rubbing, a new behavior might be for that person to place his or her hands on his or her knees, or to cross his or her arms so that the head rubbing cannot take place.2 Overview Tourette tics are involuntary, but can be influenced by internal and external factors such as stress, fatigue, excitement; the reactions of others to one's tics; either actions or reactions that are consequences or antecedents to tics being expressed.