ADHD Statistics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ADHD Parents Medication Guide Revised July 2013

ADHD Parents Medication Guide Revised July 2013 Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder Prepared by: American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry and American Psychiatric Association Supported by the Elaine Schlosser Lewis Fund Physician: ___________________________________________________ Address: ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ Phone: ___________________________________________________ Email: ___________________________________________________ ADHD Parents Medication Guide – July 2013 2 Introduction Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) is a neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by difficulty paying attention, excessive activity, and impulsivity (acting before you think). ADHD is usually identified when children are in grade school but can be diagnosed at any time from preschool to adulthood. Recent studies indicate that almost 10 percent of children between the ages of 4 to 17 are reported by their parents as being diagnosed with ADHD. So in a classroom of 30 children, two to three children may have ADHD.1,2,3,4,5 Short attention spans and high levels of activity are a normal part of childhood. For children with ADHD, these behaviors are excessive, inappropriate for their age, and interfere with daily functioning at home, school, and with peers. Some children with ADHD only have problems with attention; other children only have issues with hyperactivity and impulsivity; most children with ADHD have problems with all three. As they grow into adolescence and young adulthood, children with ADHD may become less hyperactive yet continue to have significant problems with distraction, disorganization, and poor impulse control. ADHD can interfere with a child’s ability to perform in school, do homework, follow rules, and develop and maintain peer relationships. When children become adolescents, ADHD can increase their risk of dropping out of school or having disciplinary problems. -

Reveiw Week 3 Final with Questions

REVIEW 3 SOMATIZATION AND RELATED DISORDERS SOMATIZATION AND RELATED DISORDERS SOMATIZATION ▸ Psychological problems or concerns that are converted into and communicated as physical distress ▸ Anxiety is either Conscious or Unconscious ▸ Physical Illness is Real SOMATIZATION AND RELATED DISORDERS - SSD SOMATIC SYMPTOM DISORDER A. One or more somatic symptoms that are distressing or result in significant disruption of daily life B. Excessive thoughts, feelings, or behaviors related to the somatic symptoms or associated health concerns as manifested by at least one of the following 1. Disproportionate and persistent thoughts about the seriousness or one’s symptoms 2. Persistently high level of anxiety about health or symptoms 3. Excessive time and energy devoted to these symptoms or health concerns C. Although any one somatic symptom may not be continuously present, the state of being symptomatic is persistent (typically more than 6 months) SOMATIZATION AND RELATED DISORDERS - SSD TREATMENT ▸ Regular office visits with the same physician ▸ Psychotherapy ▸ Validate the patient’s feelings/experience of symptoms SOMATIZATION AND RELATED DISORDERS - ILLNESS ANXIETY DISORDER ILLNESS ANXIETY DISORDER A. Formerly hypochondriasis B. Preoccupation with having or acquiring a serious illness C. Somatic symptoms are not present or, if present, are only mild in intensity. If another medical condition is present or there is a high risk for developing a medical condition (strong FH), the preoccupation is clearly excessive or disproportionate D. There is a high level of anxiety about health, and the individual is easily alarmed about personal health status (preoccupation with idea one is sick) E. The individual performs excessive health-related behaviors (checking body) or exhibits maladaptive avoidance (avoids doctors) F. -

Guanfacine Extended Release for ADHD

Out of the Pipeline p Guanfacine extended release for ADHD Floyd R. Sallee, MD, PhD uanfacine extended release (GXR)— Table 1 α Once-daily a selective -2 adrenergic agonist Guanfacine extended release: GFDA-approved for the treatment formulation may of attention-defi cit/hyperactivity disor- Fast facts improve adherence der (ADHD)—has demonstrated effi cacy Brand name: Intuniv and control for inattentive and hyperactive/impulsive Indication: Attention-defi cit/hyperactivity symptoms across disorder symptom domains in 2 large trials lasting® Dowden Health Media a full day 8 and 9 weeks.1,2 GXR’s once-daily formu- Approval date: September 3, 2009 lation may increase adherence and deliver Availability date: November 2009 consistent control of symptomsCopyright across a For personalManufacturer: use Shire only full day (Table 1). Dosing forms: 1-mg, 2-mg, 3-mg, and 4-mg extended-release tablets Recommended dosage: 0.05 to 0.12 mg/kg Clinical implications once daily GXR exhibits enhancement of noradren- ergic pathways through selective direct receptor action in the prefrontal cortex.3 brain believed to play a major role in at- This mechanism of action is different from tentional and organizational functions that that of other FDA-approved ADHD medi- preclinical research has linked to ADHD.3 cations. GXR can be used alone or in com- The postsynaptic α-2A receptor is bination with stimulants or atomoxetine thought to play a central role in the opti- for treating complex ADHD, such as cases mal functioning of the PFC as illustrated accompanied by oppositional features and by the “inverted U hypothesis of PFC ac- emotional dysregulation or characterized tivation.”4 In this model, cyclic adenos- by partial stimulant response. -

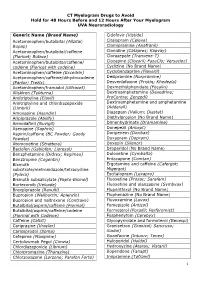

CT Myelogram Drugs to Avoid Hold for 48 Hours Before and 12 Hours After Your Myelogram UVA Neuroradiology

CT Myelogram Drugs to Avoid Hold for 48 Hours Before and 12 Hours After Your Myelogram UVA Neuroradiology Generic Name (Brand Name) Cidofovir (Vistide) Acetaminophen/butalbital (Allzital; Citalopram (Celexa) Bupap) Clomipramine (Anafranil) Acetaminophen/butalbital/caffeine Clonidine (Catapres; Kapvay) (Fioricet; Butace) Clorazepate (Tranxene-T) Acetaminophen/butalbital/caffeine/ Clozapine (Clozaril; FazaClo; Versacloz) codeine (Fioricet with codeine) Cyclizine (No Brand Name) Acetaminophen/caffeine (Excedrin) Cyclobenzaprine (Flexeril) Acetaminophen/caffeine/dihydrocodeine Desipramine (Norpramine) (Panlor; Trezix) Desvenlafaxine (Pristiq; Khedezla) Acetaminophen/tramadol (Ultracet) Dexmethylphenidate (Focalin) Aliskiren (Tekturna) Dextroamphetamine (Dexedrine; Amitriptyline (Elavil) ProCentra; Zenzedi) Amitriptyline and chlordiazepoxide Dextroamphetamine and amphetamine (Limbril) (Adderall) Amoxapine (Asendin) Diazepam (Valium; Diastat) Aripiprazole (Abilify) Diethylpropion (No Brand Name) Armodafinil (Nuvigil) Dimenhydrinate (Dramamine) Asenapine (Saphris) Donepezil (Aricept) Aspirin/caffeine (BC Powder; Goody Doripenem (Doribax) Powder) Doxapram (Dopram) Atomoxetine (Strattera) Doxepin (Silenor) Baclofen (Gablofen; Lioresal) Droperidol (No Brand Name) Benzphetamine (Didrex; Regimex) Duloxetine (Cymbalta) Benztropine (Cogentin) Entacapone (Comtan) Bismuth Ergotamine and caffeine (Cafergot; subcitrate/metronidazole/tetracycline Migergot) (Pylera) Escitalopram (Lexapro) Bismuth subsalicylate (Pepto-Bismol) Fluoxetine (Prozac; Sarafem) -

Guideline for Preoperative Medication Management

Guideline: Preoperative Medication Management Guideline for Preoperative Medication Management Purpose of Guideline: To provide guidance to physicians, advanced practice providers (APPs), pharmacists, and nurses regarding medication management in the preoperative setting. Background: Appropriate perioperative medication management is essential to ensure positive surgical outcomes and prevent medication misadventures.1 Results from a prospective analysis of 1,025 patients admitted to a general surgical unit concluded that patients on at least one medication for a chronic disease are 2.7 times more likely to experience surgical complications compared with those not taking any medications. As the aging population requires more medication use and the availability of various nonprescription medications continues to increase, so does the risk of polypharmacy and the need for perioperative medication guidance.2 There are no well-designed trials to support evidence-based recommendations for perioperative medication management; however, general principles and best practice approaches are available. General considerations for perioperative medication management include a thorough medication history, understanding of the medication pharmacokinetics and potential for withdrawal symptoms, understanding the risks associated with the surgical procedure and the risks of medication discontinuation based on the intended indication. Clinical judgement must be exercised, especially if medication pharmacokinetics are not predictable or there are significant risks associated with inappropriate medication withdrawal (eg, tolerance) or continuation (eg, postsurgical infection).2 Clinical Assessment: Prior to instructing the patient on preoperative medication management, completion of a thorough medication history is recommended – including all information on prescription medications, over-the-counter medications, “as needed” medications, vitamins, supplements, and herbal medications. Allergies should also be verified and documented. -

Medications Used for Behavioral and Emotional Disorders: a Guide for Parents, Foster Parents

MEDICATIONS USED FOR BEHAVIORAL & EMOTIONAL DISORDERS A GUIDE FOR PARENTS, FOSTER PARENTS, FAMILIES, YOUTH, CAREGIVERS, GUARDIANS, AND SOCIAL WORKERS Final May 10, 2010 Overview This booklet is a guide for parents and other caregivers to help you understand the medications that are sometimes used to help children with behavioral or emotional problems. Being able to talk openly with your child’s doctor or other health care provider is very important. This guide may make it easier for you to talk with your child's doctors about medications. You will find information about the medications that may be used to help treat these conditions in children. How these medications work and possible side effects are also included. As a parent or caregiver of a child with a behavioral or emotional disorder, you may be feeling overwhelmed as you try to help your child cope with his or her problems. Many parents and caregivers feel that nobody understands the frustration of caring for a child with a behavioral or emotional disorder. But many other families are in the same situation. According to one study, over 4 million children ages 9 to 17 have some kind of emotional or behavioral problem that affects their daily lives. 2 Getting Help Children with behavioral or emotional disorders are a special group and need special care. Many times children have symptoms that are different from adults with the same disorder. Symptoms may also vary from child to child, and it can be difficult to understand a child's signs and symptoms. Children may have trouble understanding their illness and may not be able to describe how they feel. -

Challenges in Managing Treatment-Refractory Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder and Tourette’S Syndrome Paulo Lizano, MD, Phd, Ami Popat-Jain, MA, Jeremiah M

CLINICAL CHALLENGE Editor: Joji Suzuki, MD Challenges in Managing Treatment-Refractory Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder and Tourette’s Syndrome Paulo Lizano, MD, PhD, Ami Popat-Jain, MA, Jeremiah M. Scharf, MD, PhD, Noah C. Berman, PhD, Alik Widge, MD, PhD, Darin D. Dougherty, MD, MMSc, and Emad Eskandar, MD, MBA Keywords: cognitive-behavioral therapy, deep brain stimulation, exposure response prevention, memantine, obsessive-compulsive disorder, Tourtette’s syndrome CASE HISTORY to our PHP and, because of his outbursts, forced to live in Mr. R was a 19-year-old, single, unemployed, homeless His- the associated shelter. On admission, he endorsed his mood panic male with a history of Tourette’s syndrome (TS), obsessive- as “sad.” He admitted to having tics (vocalizations, moving compulsive disorder (OCD), attention-deficit/hyperactivity foot, head, scratching) and OCD symptoms (looking at things disorder (ADHD), and posttraumatic stress disorder. In ad- a certain number of times, obsession with symmetry, and star- dition, he suffered from suicidal ideation, self-injurious ing at a corner) that lasted the whole day. He endorsed anxi- behavior (superficial cutting and head banging), anxiety, de- ety that consisted of general worry and ruminations about the pression, and anger outbursts. He was referred to our cognitive- past. He denied any manic or psychotic symptoms, as well as behavioral therapy (CBT) partial hospitalization program (PHP) suicidal or homicidal ideation. and associated homeless shelter for the targeted treatment of his Developmentally, the patient was born at 40 weeks gesta- OCD, TS, and anger outbursts after being discharged from tion,birthweight8lbs,2oz,anddeliveredbynormalspontane- a psychiatric hospital. ous vaginal delivery, with no prenatal or perinatal complications. -

Pediatric Sleep Disturbance

Pediatric Sleep Disturbance Identification of Problems & Strategies for Management in Primary Care Justin Schreiber D.O., MPH, FAAP Ryan Anderson Ph.D. Objectives • Establish the impact of sleep problems, describe normal sleep, & define sleep physiology • Establish familiarity with a sleep screener that can be used in primary care (PC) with goals of: – Outlining common sleep presentations – Describing corresponding practical recommendations for the PC setting – Determining when to consider sub-specialty referral • Medication management options in PC Relevance of Pediatric Sleep Problems How Common Are They? Why Be Concerned? Occurrence of Sleep Disorders • Insomnia – 20% or more in young children (Mindell et al., 2006) • Insufficient sleep – 62% in teens (NSF, 2006) • DSPD – 7% teens • OSA – 1% to 4% (Lumeng & Chervin, 2008) • Narcolepsy – 0.05% (Longstreth et al., 2007) • Parasomnias – Recurrent nightmares – 1% to 5% (Li et al., 2011) – Recurrent sleep terrors ages 4 to 12 – 1% to 7% (AASM, 2014) – Sleep walking 5% • RLS 2% - 6%, which is associated with PLMD and ADHD (Picchietti et al., 2013) Parents’ and Teens’ Perceptions • 25% to 33% of parents think their toddler, pre-, or school-age child doesn’t get enough sleep. – Few children “outgrow” sleep problems; e.g., 84% of infants 3 years later (Owens et al., 2000) • 9% of parents think their teen has a sleep prob • 24% of teens think they have a sleep prob – Depending on age, 29% to 56% getting < 7 hrs! – 51% report EDS at least once per week National Sleep Foundation (2014, 2006, 2004) -

Beyond Amitriptyline

children Review Beyond Amitriptyline: A Pediatric and Adolescent Oriented Narrative Review of the Analgesic Properties of Psychotropic Medications for the Treatment of Complex Pain and Headache Disorders Robert Blake Windsor 1,2,*, Michael Sierra 2,3, Megan Zappitelli 2,3 and Maria McDaniel 1,2 1 Division of Pediatric Pain Medicine, Department of Pediatrics, Prisma Health, Greenville, SC 29607, USA; [email protected] 2 School of Medicine Greenville, University of South Carolina, Greenville, SC 29607, USA; [email protected] (M.S.); [email protected] (M.Z.) 3 Division of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Department of Psychiatry, Prisma Health, Greenville, SC 29607, USA * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 30 October 2020; Accepted: 25 November 2020; Published: 2 December 2020 Abstract: Children and adolescents with recurrent or chronic pain and headache are a complex and heterogenous population. Patients are best served by multi-specialty, multidisciplinary teams to assess and create tailored, individualized pain treatment and rehabilitation plans. Due to the complex nature of pain, generalizing pharmacologic treatment recommendations in children with recurrent or chronic pains is challenging. This is particularly true of complicated patients with co-existing painful and psychiatric conditions. There is an unfortunate dearth of evidence to support many pharmacologic therapies to treat children with chronic pain and headache. This narrative review hopes to supplement the available treatment options for this complex population by reviewing the pediatric and adult literature for analgesic properties of medications that also have psychiatric indication. The medications reviewed belong to medication classes typically described as antidepressants, alpha 2 delta ligands, mood stabilizers, anti-psychotics, anti-sympathetic agents, and stimulants. -

Systematic Evidence Review from the Blood Pressure Expert Panel, 2013

Managing Blood Pressure in Adults Systematic Evidence Review From the Blood Pressure Expert Panel, 2013 Contents Foreword ............................................................................................................................................ vi Blood Pressure Expert Panel ..............................................................................................................vii Section 1: Background and Description of the NHLBI Cardiovascular Risk Reduction Project ............ 1 A. Background .............................................................................................................................. 1 Section 2: Process and Methods Overview ......................................................................................... 3 A. Evidence-Based Approach ....................................................................................................... 3 i. Overview of the Evidence-Based Methodology ................................................................. 3 ii. System for Grading the Body of Evidence ......................................................................... 4 iii. Peer-Review Process ....................................................................................................... 5 B. Critical Question–Based Approach ........................................................................................... 5 i. How the Questions Were Selected ................................................................................... 5 ii. Rationale for the Questions -

22037 Guanfacine Clinpharm PREA

CLINICAL REVIEW Application Type: NDA Submission Number: 22,037 Submission Code: Letter Date: August 24, 2006 Stamp Date: August 27, 2006 PDUFA Goal Date: June 24, 2007 Reviewer Name: Robert L. Levin, M.D. Review Completion Date: June 12, 2007 Established Name: Guanfacine hydrochloride Proposed Trade Name: Intuniv Therapeutic Class: Central ά-2adrenergic-receptor agonist Applicant: Shire Priority Designation: S Formulation: Oral, extended-release tablet Dosing Regimen: Once daily Indication: Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity D/O Intended Population: Pediatrics (ages 6-17) 1 Table of Contents 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY……………………………………………………………5 1.1 RECOMMENDATION ON REGULATORY ACTION………………………………5 1.2 RECOMMENDATIONS ON POSTMARKETING ACTIONS…………………..……5 1.2.1 Risk Management Activity……………………………………………………….6 1.2.2 Required Phase 4 Commitments…………………………………………………6 1.2.3 Other Phase 4 Requests……………………………………………………………6 1.3 SUMMARY OF CLINICAL FINDINGS………………………………………………6 1.3.1 Brief Overview of the Clinical Program………………………………………….6 1.3.2 Efficacy………………………………………………………………………….…..7 1.3.3 Safety……………………………………………………………………………..7 1.3.4 Dosing Regimen and Administration………………………………………………9 1.3.5 Drug-Drug Interactions……………………………………………………………10 1.3.6 Special Populations………………………………………………………………..11 2 INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND……………………………….......................13. 2.1 PRODUCT INFORMATION………………………………………………………..…13 2.2 CURRENTLY AVAILABLE TREATMENTS FOR INDICATION………………….14 2.3 AVAILABILITY OF PROPOSED ACTIVE INGREDIENT IN THE U.S…………….14 2.4 IMPORTANT ISSUES WITH PHARMACOLOGICALLY -

Guanfacine (Intuniv) for Attention-Deficit/ Hyperactivity Disorder ALLISON BERNKNOPF, Pharmd, BCPS, Ferris State University, Kalamazoo, Michigan

STEPS New Drug Reviews Guanfacine (Intuniv) for Attention-Deficit/ Hyperactivity Disorder ALLISON BERNKNOPF, PharmD, BCPS, Ferris State University, Kalamazoo, Michigan STEPS new drug reviews Guanfacine (Intuniv) is an extended-release, non–central nervous system stimulant approved cover Safety, Tolerability, for the treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in children six to 17 Effectiveness, Price, and Simplicity. Each indepen- years of age; however, it appears to be most effective in children 12 years or younger. Simi- dent review is provided lar to clonidine (Catapres), it works as a selective agonist for the a2A-adrenergic receptor, by authors who have no although the actual mechanism of action is not known. financial association with the drug manufacturer. The series coordinator for Approximate AFP is Allen F. Shaugh- Drug Starting dosage Dose form monthly cost* nessy, PharmD, Tufts University Family Medicine Guanfacine 1 mg per day 1-mg, 2-mg, 3-mg, or 4-mg extended- $156 (2 to 3 mg Residency Program at (Intuniv) release tablets per day) Cambridge Health Alli- ance, Malden, Mass. *—Estimated retail price of one month’s treatment based on information obtained at http://www.drugstore.com (accessed August 16, 2010). A collection of STEPS pub- lished in AFP is available at http://www.aafp.org/ afp/steps. SAFETY tend to decrease over time; most patients Guanfacine can cause hypotension, although report not having these effects by the end of it does not cause symptoms in most patients, the eight- to nine-week treatment period.2-4 and changes in blood pressure are usually The dosage should be slowly titrated up to small.