THE CAMPAIGN CASINO, Who Wins

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Routledge Handbook of Political Management

This article was downloaded by: 10.3.98.104 On: 03 Oct 2021 Access details: subscription number Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: 5 Howick Place, London SW1P 1WG, UK Routledge Handbook of Political Management Dennis W. Johnson Political Consulting Worldwide Publication details https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/doi/10.4324/9780203892138.ch3 Fritz Plasser Published online on: 22 Aug 2008 How to cite :- Fritz Plasser. 22 Aug 2008, Political Consulting Worldwide from: Routledge Handbook of Political Management Routledge Accessed on: 03 Oct 2021 https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/doi/10.4324/9780203892138.ch3 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR DOCUMENT Full terms and conditions of use: https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/legal-notices/terms This Document PDF may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproductions, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The publisher shall not be liable for an loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material. Downloaded By: 10.3.98.104 At: 02:49 03 Oct 2021; For: 9780203892138, chapter3, 10.4324/9780203892138.ch3 First published 2009 by Routledge 270 Madison Ave, New York, NY 10016 Simultaneously published in the UK by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business © 2009 Taylor & Francis; individual chapters, the contributors This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2008. -

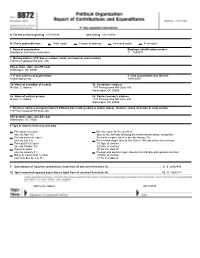

A for the Period Beginning 01/01/2014 and Ending 03/31/2014

A For the period beginning 01/01/2014 and ending 03/31/2014 B Check applicable box: ✔ Initial report Change of address Amended report Final report 1 Name of organization Employer identification number Republican Governors Association 11 - 3655877 2 Mailing address (P.O. box or number, street, and room or suite number) 1747 Pennsylvania NW Suite 250 City or town, state, and ZIP code Washington, DC 20006 3 E-mail address of organization: 4 Date organization was formed: [email protected] 10/04/2002 5a Name of custodian of records 5b Custodian's address Michael G. Adams 1747 Pennsylvania NW Suite 250 Washington, DC 20006 6a Name of contact person 6b Contact person's address Michael G. Adams 1747 Pennsylvania NW Suite 250 Washington, DC 20006 7 Business address of organization (if different from mailing address shown above). Number, street, and room or suite number 1747 Pennsylvania NW Suite 250 City or town, state, and ZIP code Washington, DC 20006 8 Type of report (check only one box) ✔ First quarterly report Monthly report for the month of: (due by April 15) (due by the 20th day following the month shown above, except the Second quarterly report December report, which is due by January 31) (due by July 15) Pre-election report (due by the 12th or 15th day before the election) Third quarterly report (1) Type of election: (due by October 15) (2) Date of election: Year-end report (3) For the state of: (due by January 31) Post-general election report (due by the 30th day after general election) Mid-year report (Non-election (1) Date of election: year only-due by July 31) (2) For the state of: 9 Total amount of reported contributions (total from all attached Schedules A) .......................................................................... -

Coordination Reconsidered

Columbia Law School Scholarship Archive Faculty Scholarship Faculty Publications 2013 Coordination Reconsidered Richard Briffault Columbia Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.columbia.edu/faculty_scholarship Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Richard Briffault, Coordination Reconsidered, 113 COLUM. L. REV. SIDEBAR 88 (2013). Available at: https://scholarship.law.columbia.edu/faculty_scholarship/19 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Publications at Scholarship Archive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Scholarship Archive. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COLUMBIA LAW REVIEW SIDEBAR VOL. 113 MAY 2, 2013 PAGES 88-101 COORDINATION RECONSIDERED Richard Briffault* At the heart of American campaign finance law is the distinction drawn by the Supreme Court in Buckley v. Valeo between contributions and expenditures. 1 According to the Court, contributions may be limited because they pose the dangers of corruption and the appearance of corruption, but expenditures pose no such dangers and therefore may not be limited. The distinction between the two types of campaign spending turns not on the form-the fact that contributions proceed from a donor to a candidate, while expenditures involve direct efforts to influence the voters-but on whether the campaign practice implicates the corruption concerns that the Court has held justify campaign finance regulation. As a result, not all expenditures are exempt from restriction. 2 Independent expenditures undertaken by an individual or group in support of a candidate or against her opponent are constitutionally protected from limitation. -

2018 Conference Program

CONFERENCE PROGRAM THE FSU REAL ESTATE CENTER’S 24TH REAL ESTATE TRENDS CONFERENCE OCTOBER 25 & 26 , 2 0 18 TALLAHASSEE, FLORIDA LEGACY LEADERS GOLD SPONSORS PROGRAM PARTNERS The Real Estate TRENDS Conference is organized to inform participants of the The Program Partner designation is reserved for emerging trends and issues facing the real estate industry, to establish and strengthen those who have made major gifts to advance the professional contacts, and to present the broad range of career opportunities available Real Estate Program at Florida State University. to our students. It is organized by the FSU Real Estate Center, the Florida State University Donna Abood Real Estate Network and the students’ FSU Real Estate Society. This event would not be Beth Azor possible without the generous financial support of its sponsors. Kenneth Bacheller Mark C. Bane Bobby Byrd LEGACY LEADERS Harold and Barbara Chastain Centennial Management Corp. Marshall Cohn Peter and Jennifer Collins JLL John Crossman/Crossman & Company The Kislak Family Foundation, Inc. Scott and Marion Darling Florida State Real Estate Network, Inc. Mark and Nan Casper Hillis Evan Jennings GOLD SPONSORS The Kislak Family Foundation, Inc. • Berkadia • Cushman & Wakefield • Lennar Homes Brett and Cindy Lindquist • Carroll Organization • The Dunhill Companies • The Nine @ Tallahassee George Livingston William and Stephanie Lloyd • CBRE • Eastdil Secured • Osprey Capital Shawn McIntyre/North American Properties • CNL Financial Group, Inc. • Florida Trend • Ryan, LLC Greg Michaud • Colliers International • Gilbane Building Company • Stearns Weaver Miller Kyle Mowitz and Justin Mowitz • Commercial Capital LTD • GreenPointe Communities, LLC • STR, Inc. Francis Nardozza • Culpepper Construction • Hatfield Development/Pou • Walker & Dunlop Kyle D. -

The Rise and Impact of Fact-Checking in U.S. Campaigns by Amanda Wintersieck a Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment O

The Rise and Impact of Fact-Checking in U.S. Campaigns by Amanda Wintersieck A Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy Approved April 2015 by the Graduate Supervisory Committee: Kim Fridkin, Chair Mark Ramirez Patrick Kenney ARIZONA STATE UNIVERSITY May 2015 ABSTRACT Do fact-checks influence individuals' attitudes and evaluations of political candidates and campaign messages? This dissertation examines the influence of fact- checks on citizens' evaluations of political candidates. Using an original content analysis, I determine who conducts fact-checks of candidates for political office, who is being fact- checked, and how fact-checkers rate political candidates' level of truthfulness. Additionally, I employ three experiments to evaluate the impact of fact-checks source and message cues on voters' evaluations of candidates for political office. i DEDICATION To My Husband, Aza ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I wish to express my sincerest thanks to the many individuals who helped me with this dissertation and throughout my graduate career. First, I would like to thank all the members of my committee, Professors Kim L. Fridkin, Patrick Kenney, and Mark D. Ramirez. I am especially grateful to my mentor and committee chair, Dr. Kim L. Fridkin. Your help and encouragement were invaluable during every stage of this dissertation and my graduate career. I would also like to thank my other committee members and mentors, Patrick Kenney and Mark D. Ramirez. Your academic and professional advice has significantly improved my abilities as a scholar. I am grateful to husband, Aza, for his tireless support and love throughout this project. -

Office of Career Services Political Consulting Firms

OFFICE OF CAREER SERVICES POLITICAL CONSULTING FIRMS A.B. Data Ltd. A.B. Data provides services in areas including integrated fundraising, direct mail, digital fundraising, analytics and planning, list services, and production management. The firm has offices in Washington DC, Wisconsin, and New York. www.abdata.com California Strategies, LLC California Strategies is a full-service public strategy firm that focuses on helping clients navigate through California’s political, regulatory, legislative, and media environments on a state and local level. The firm is located in California. www.calstrat.com Campaign Solutions Campaign Solutions is a full-service online consulting firm specializing in fundraising, advertising, mobile, social media, and web development. The firm has offices in Virginia, New Jersey, and California. www.campaignsolutions.com The Campaign Workshop The Campaign Workshop is a full-service political consulting firm that specializes in direct mail, print, and online advertising for issue advocacy, candidate, and ballot initiative campaigns. The firm is located in Washington, DC. www.thecampaignworkshop.com The Eppstein Group The Eppstein Group specializes in advertising, public relations, opinion polling, and elections. The firm is located in Texas. www.eppsteingroup.com First Tuesday Strategies First Tuesday Strategies is a full-service political and grassroots consulting firm that specializes in areas such as campaign strategy, online and print media, direct mail, video and radio production, marketing, and advertising. The firm is located in South Carolina. www.firsttuesdaystrategies.com Global Strategy Group Global Strategy Group (GSG) is a public affairs and research firm specializing in research, strategic communications, digital strategy, grassroots and grasstops organizing, marketing and branding. -

Gone Rogue: Time to Reform the Presidential Primary Debates

Joan Shorenstein Center on the Press, Politics and Public Policy Discussion Paper Series #D-67, January 2012 Gone Rogue: Time to Reform the Presidential Primary Debates by Mark McKinnon Shorenstein Center Reidy Fellow, Fall 2011 Political Communications Strategist Vice Chairman Hill+Knowlton Strategies Research Assistant: Sacha Feinman © 2012 President and Fellows of Harvard College. All rights reserved. How would the course of history been altered had P.T. Barnum moderated the famed Lincoln-Douglas debates in 1858? Today’s ultimate showman and on-again, off-again presidential candidate Donald Trump invited the Republican presidential primary contenders to a debate he planned to moderate and broadcast over the Christmas holidays. One of a record 30 such debates and forums held or scheduled between May 2011 and March 2012, this, more than any of the previous debates, had the potential to be an embarrassing debacle. Trump “could do a lot of damage to somebody,” said Karl Rove, the architect of President George W. Bush’s 2000 and 2004 campaigns, in an interview with Greta Van Susteren of Fox News. “And I suspect it’s not going to be to the candidate that he’s leaning towards. This is a man who says himself that he is going to run— potentially run—for the president of the United States starting next May. Why do we have that person moderating a debate?” 1 Sen. John McCain of Arizona, the 2008 Republican nominee for president, also reacted: “I guarantee you, there are too many debates and we have lost the focus on what the candidates’ vision for America is.. -

Effective Ads and Social Media Promotion

chapter2 Effective Ads and Social Media Promotion olitical messages are fascinating not only because of the way they are put together but also because of their ability to influence voters. People are Pnot equally susceptible to the media, and political observers have long tried to find out how media power actually operates.1 Consultants judge the effective- ness of ads and social media outreach by the ultimate results—who distributewins. This type of test, however, is never possible to complete until after the election. It leads invariably to the immutable law of communications: Winners have great ads and tweets, losers do not. or As an alternative, journalists evaluate communications by asking voters to indicate whether commercials influenced them. When asked directly whether television commercials helped them decide how to vote, most voters say they did not. For example, the results of a Media Studies Center survey placed ads at the bottom of the heap in terms of possible information sources. Whereas 45 percent of voters felt they learned a lot from debates, 32 percent cited newspa- per stories, 30 percent pointed to televisionpost, news stories, and just 5 percent believed they learned a lot from political ads. When asked directly about ads in a USA Today/Gallup poll, only 8 percent reported that presidential candidate ads had changed their views.2 But this is not a meaningful way of looking at advertising. Such responses undoubtedly reflect an unwillingness to admit that external agents have any effect on individual voting behavior. Many people firmly believe that they make up their copy,minds independently of partisan campaign ads. -

Trump the Ultimate INGOP Wildcard

V21, N25 Friday, March 4, 2016 Trump the ultimate INGOP wildcard could go wrong A few Hoosier with that?), prepar- ing to nominate a Republicans express billionaire dema- alarm, but party is gogue who has insulted everyone mostly mute from the Holy See to disabled citizens. By BRIAN A. HOWEY The only entities BLOOMINGTON – We have not feeling the entered the era of Trumpian Indi- Teflon howitzers ana. It is one filled with mystery and are Jesus Christ, vacuum. It is one that is releasing Mohammed and demons. With Donald Trump well God, and they positioned for may be next. For the Republican Democrats rejoic- presidential ing at the idea that nomination, Hillary Clinton will fueled by about Andrean HS students holding a Donald Trump cutout chanted “build a “cream” Trump, as 35% of the wall” at Latino Bishop Noll students last weekend. (NWI Times Photo) suggested by the Republican wobbly prognosti- electorate in about 15 states, Americans and Hoosiers are cators Karl Rove and Bill Kristol, the sobering dynamic is facing an unprecedented November election with the likely that the U.S. may be one terror assault away from a Presi- nominees possessing historically high negatives. dent Trump, whose candidacy rocketed past the punditry Any historic templates are now obsolete. following the Paris and San Bernardino attacks. ISIS seeks On the Republican side, the Trump phenomenon is Continued on page 4 being propelled by the uneducated and uninformed (what Lt. Gov. Holcomb ascends By BRIAN A. HOWEY INDIANAPOLIS – Sooooo, have you been to the Berry Bowl? Eric Holcomb responded, “Yes.” The Wigwam? TigArena? Northside Gym? Holcomb, then a U.S. -

An Overview of My Internship with Congressman David Skaggs and How This Set a Course for My Career in Political Campaigning

Erin Ainsworth Fish Summer 2016 Independent Study Course An overview of my internship with Congressman David Skaggs and how this set a course for my career in political campaigning. By my senior year at CU I had changed my major twice and had gone from dreaming of a career as a journalist and traveling the world working for National Geographic, to serving in the Peace Corp and teaching English in West Africa. I was all over the map as far as picking out a career for myself and couldn’t hone in on one area of interest. I excelled in foreign languages and history but there didn’t seem to be a job which I could envision in those areas and my father wasn’t too subtle about what he’d like me to pursue by sending me articles on beginning salaries for lawyers. He was a maritime lawyer and felt that the law was a perfect career. I had settled on a major in Political Science as I had always been interested in government and my mother was particularly active in local politics. She had a heavy influence on my knowledge of current affairs and our dinner conversations were about the war in Iran and the Ayatollah Khomeini, the Civil Rights movement which she was passionate about, or we’d discuss the Kennedy assassinations and what that meant to her generation. Politics and American Government felt familiar to me and it seemed like a natural progression to major in political science. However I knew I didn’t want to pursue a career in the law and yet nothing stood out as an “aha!” job for me and with that came a constant level of anxiety. -

Even After Multiple Credible Accusations, Top Anti-Choice Advocacy Organizations Stand by Kavanaugh at All Costs Anti-Choice Ac

Even After Multiple Credible Accusations, Top Anti-Choice Advocacy Organizations Stand By Kavanaugh At All Costs Susan B. Anthony List said they are “proud to continue supporting Judge Kavanaugh and we urge the U.S. Senate to confirm him as soon as possible.” The comments came in a September 24th statement, after multiple credible accusations of sexual assault had come to light. [Susan B. Anthony List, 9/24/18] Operation Rescue: “Operation Rescue Stands Behind Judge Kavanaugh in Face of Gutter-Level Attacks.” [Twitter, 9/24/18] Priests For Life’s Frank Pavone tweeted: “We need to pray more than ever for #JudgeKavanaugh and his family! Let us also pray for @POTUS Trump to be able to drain the swamp in Washington!” [Twitter, 8/24/18] Anti-Choice Activists Have Dismissed Credible Allegations That Kavanagh Is Sexual Assaulter, In Favor Of Undermining Or Gutting Roe Students for Life’s Kristan Hawkins: Kavanaugh “is in the political battle of his life because of the abortion lobby’s efforts to keep Roe v. Wade the law of the land.” Responding to Dr. Christine Blasey Ford’s account of sexual assault by Supreme Court nominee Brett Kavanaugh, Students for Life President Kristan Hawkins told Rewire News: “We want to see the process go forward to vet the current allegations, but, in looking at the way in which the charges were handled (hidden until the hearings were over and handled by those who have been very public about their goal to oppose this nominee no matter what), we still see Judge Kavanaugh as a qualified candidate who is in the political battle of his life because of the abortion lobby’s efforts to keep Roe v. -

True Conservative Or Enemy of the Base?

Paul Ryan: True Conservative or Enemy of the Base? An analysis of the Relationship between the Tea Party and the GOP Elmar Frederik van Holten (s0951269) Master Thesis: North American Studies Supervisor: Dr. E.F. van de Bilt Word Count: 53.529 September January 31, 2017. 1 You created this PDF from an application that is not licensed to print to novaPDF printer (http://www.novapdf.com) Page intentionally left blank 2 You created this PDF from an application that is not licensed to print to novaPDF printer (http://www.novapdf.com) Table of Content Table of Content ………………………………………………………………………... p. 3 List of Abbreviations……………………………………………………………………. p. 5 Chapter 1: Introduction…………………………………………………………..... p. 6 Chapter 2: The Rise of the Conservative Movement……………………….. p. 16 Introduction……………………………………………………………………… p. 16 Ayn Rand, William F. Buckley and Barry Goldwater: The Reinvention of Conservatism…………………………………………….... p. 17 Nixon and the Silent Majority………………………………………………….. p. 21 Reagan’s Conservative Coalition………………………………………………. p. 22 Post-Reagan Reaganism: The Presidency of George H.W. Bush……………. p. 25 Clinton and the Gingrich Revolutionaries…………………………………….. p. 28 Chapter 3: The Early Years of a Rising Star..................................................... p. 34 Introduction……………………………………………………………………… p. 34 A Moderate District Electing a True Conservative…………………………… p. 35 Ryan’s First Year in Congress…………………………………………………. p. 38 The Rise of Compassionate Conservatism…………………………………….. p. 41 Domestic Politics under a Foreign Policy Administration……………………. p. 45 The Conservative Dream of a Tax Code Overhaul…………………………… p. 46 Privatizing Entitlements: The Fight over Welfare Reform…………………... p. 52 Leaving Office…………………………………………………………………… p. 57 Chapter 4: Understanding the Tea Party……………………………………… p. 58 Introduction……………………………………………………………………… p. 58 A three legged movement: Grassroots Tea Party organizations……………... p. 59 The Movement’s Deep Story…………………………………………………… p.