Summary of the Workshop “Rethinking Creativity, Recognition and Indigeneity”1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Los Kjarkas Historia Jamás Contada

LOS KJARKAS: LA HISTORIA NO CONTADA LOS KJARKAS Actual formación de Los Kjarkas Introducción: Los más grandes de entre los grandes, los músicos andinos que han llevado al folklore latinoamericano a lo más alto, son sin duda alguna Los Kjarkas, un grupo que revolucionó el arte musical andino hace ya casi 50 años y que a lo largo de toda una vida nos han deleitado con impagables obras maestras con mayúsculas. Y es que todo en Los Kjarkas es grandioso: grandes músicos, grandes composiciones y una gran historia, por él han pasado intérpretes y compositores de gran calibre, manteniendo siempre un núcleo familiar en torno a la familia Hermosa. Sin embargo, no todo ha sido alegría, comprensión u honestidad dentro del grupo. En muchos foros, entrevistas o videos, se habla sobre la historia de los Kjarkas, pero se ha omitido gran parte de esta historia, historia que leerás hoy día. Es esta pues, la historia oculta de Los Kjarkas. LOS KJARKAS: LA HISTORIA NO CONTADA Advertencias: - Si eres una persona conservadora, un fanático a morir de Los Kjarkas, que los ve como “ídolos”, que no podrían hacer malo, y no deseas “tener” una mala imagen de ellos, te pido que dejes de leer este artículo, porque podrías cambiar de mirada y llevarte un gran disgusto. - Durante la historia, se nombrarán a otros grupos, que son necesarios de nombrar para poder entender la historia de Los Kjarkas. LOS KJARKAS: LA HISTORIA NO CONTADA Etimología del nombre: Sobre el nombre “Kjarkas” no hay nada dicho ciertamente. Se manejan dos significados y orígenes que se contradicen. -

C:\010 MWP-Sonderausgaben (C)\D

Dancando Lambada Hintergründe von S. Radic "Dançando Lambada" is a song of the French- Brazilian group Kaoma with the Brazilian singer Loalwa Braz. It was the second single from Kaomas debut album Worldbeat and followed the world hit "Lambada". Released in October 1989, the album peaked in 4th place in France, 6th in Switzerland and 11th in Ireland, but could not continue the success of the previous hit single. A dub version of "Lambada" was available on the 12" and CD maxi. In 1976 Aurino Quirino Gonçalves released a song under his Lambada-Original is the title of a million-seller stage name Pinduca under the title "Lambada of the international group Kaoma from 1989, (Sambão)" as the sixth title on his LP "No embalo which has triggered a dance wave with the of carimbó and sirimbó vol. 5". Another Brazilian dance of the same name. The song Lambada record entitled "Lambada das Quebradas" was is actually a plagiarism, because music and then released in 1978, and at the end of 1980 parts of the lyrics go back to the original title several dance halls were finally created in Rio de "Llorando se fue" ("Crying she went") of the Janeiro and other Brazilian cities under the name Bolivian folklore group Los Kjarkas from the "Lambateria". Márcia Ferreira then remembered Municipio Cochabamba. She had recorded this forgotten Bolivian song in 1986 and recorded the song composed by Ulises Hermosa and a legal Portuguese cover version for the Brazilian his brother Gonzalo Hermosa-Gonzalez, to market under the title Chorando se foi (same which they dance Saya in Bolivia, for their meaning as the Spanish original) with Portuguese 1981 LP Canto a la mujer de mi pueblo, text; but even this version remained without great released by EMI. -

INSTRUMENTAL ENSEMBLE Catalog Addendum

HAL LEONARD INSTRUMENTAL2012 ENSEMBLE catalog addendum Concert Band • Marching Band • Jazz Ensemble • Orchestra • Essential Elements • Rubank • Methods This brochure details products which have been created since publishing the 2011-2012 Hal Leonard Instrumental Ensemble Catalog. Please see this catalog, HL 90008184, for a complete listing of titles available, or visit our website at www.halleonard.com 1033585 Addendum.indd 1 5/18/12 2:31 PM 2 MARCHING BAND Inv. No. Title (Arranger) Series/Grade Price Inv. No. Title (Arranger) Series/Grade Price _____ 40004100 30-Second Blasters _____ 03745581 Kernkraft 400 (arr. Jay Dawson/Jim Reed) ......APCMB3 ......... $60.00 (arr. Paul Lavender/Will Rapp) ..CNTMB3 ......... $55.00 _____ 03745577 Afro Blue _____ 03745573 Kickbutt Cadences Vol. 2 (arr. Paul Murtha/Will Rapp)......ESPRT2 .......... $55.00 (Will Rapp) ................................ESPRT3 .......... $45.00 _____ 40004084 Americano (arr. Tom Wallace/ _____ 03745569 The Lady Is a Tramp Tony McCutchen) ......................APCMB3 ......... $60.00 (arr. Paul Murtha/Will Rapp)......PFELT4 ........... $65.00 _____ 40004080 Blackbird/Yesterday _____ 40004076 Magical Mystery Tour/Lady Madonna (arr. Tom Wallace) .....................APCMB3 ......... $80.00 (arr. Tom Wallace) .....................APCMB3 ......... $80.00 _____ 40004102 Bully(arr. Tom Wallace/ _____ 03745579 Misirlou (arr. Tim Waters) ...........ESPRT2 .......... $55.00 Tony McCutchen) ......................APCMB3 ......... $60.00 _____ 40004094 Moves like Jagger (arr. Tom Wallace/ _____ 03745563 Captain America March Tony McCutchen) ......................APCMB3 ......... $60.00 (arr. Paul Murtha) ......................PFELT3 ........... $65.00 _____ 40004096 On the Floor (arr. Tom Wallace/ _____ 03745567 Come Fly with Me (arr. Paul Murtha/ Tony McCutchen) ......................APCMB3 ......... $70.00 Will Rapp) ..................................PFELT4 ........... $65.00 _____ 03745565 Party Rock Anthem _____ 03745601 Crocodile Rock (arr. -

Performing Blackness in the Danza De Caporales

Roper, Danielle. 2019. Blackface at the Andean Fiesta: Performing Blackness in the Danza de Caporales. Latin American Research Review 54(2), pp. 381–397. DOI: https://doi.org/10.25222/larr.300 OTHER ARTS AND HUMANITIES Blackface at the Andean Fiesta: Performing Blackness in the Danza de Caporales Danielle Roper University of Chicago, US [email protected] This study assesses the deployment of blackface in a performance of the Danza de Caporales at La Fiesta de la Virgen de la Candelaria in Puno, Peru, by the performance troupe Sambos Illimani con Sentimiento y Devoción. Since blackface is so widely associated with the nineteenth- century US blackface minstrel tradition, this article develops the concept of “hemispheric blackface” to expand common understandings of the form. It historicizes Sambos’ deployment of blackface within an Andean performance tradition known as the Tundique, and then traces the way multiple hemispheric performance traditions can converge in a single blackface act. It underscores the amorphous nature of blackface itself and critically assesses its role in producing anti-blackness in the performance. Este ensayo analiza el uso de “blackface” (literalmente, cara negra: término que designa el uso de maquillaje negro cubriendo un rostro de piel más pálida) en la Danza de Caporales puesta en escena por el grupo Sambos Illimani con Sentimiento y Devoción que tuvo lugar en la fiesta de la Virgen de la Candelaria en Puno, Perú. Ya que el “blackface” es frecuentemente asociado a una tradición estadounidense del siglo XIX, este artículo desarrolla el concepto de “hemispheric blackface” (cara-negra hemisférica) para dar cuenta de elementos comunes en este género escénico. -

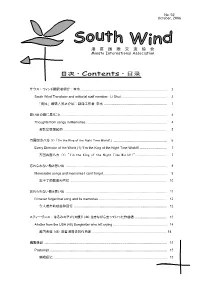

No.52 That Unforgettable Song and What It Means to Me

No. 52 October, 2006 ᷼࿖㓙ᵹදળ Minato International Association ⋡ᰴ 䊶 Contents 䊶 Ⳃᔩ 䉰䉡䉴 䊶 䉡䉞䊮䊄⠡⸶⠪⚫ 䋺 ᧘᳓ ............................................................................................ 2 South Wind Translator and editorial staff member: Li Shui ................................................. 3 Njफ亢nj㓪䕥ҎਬПҟ㒡ĩ㗏䆥Ꮉ㗙ᴢ∈ ................................................................... 3 ᗐ䈇䈱䈮ᕁ䈉䈖䈫 ................................................................................................................. 4 Thoughts from songs in Memories....................................................................................... 4 㗕℠䅽៥ᛇ䍋ⱘ .............................................................................................................. 5 ਁ࿖྾ᣇᣇ㩷㩿㪈㪀 䇸㪠㩾㫄㩷㫋㪿㪼㩷㪢㫀㫅㪾㩷㫆㪽㩷㫋㪿㪼㩷㪥㫀㪾㪿㫋㩷㪫㫀㫄㪼㩷㪮㫆㫉㫃㪻㩸㩸䇹 ......................................................... 6 Every Direction of the World (1) “I’m the King of the Night Time World!! ............................. 7 ϛಯ䴶ܿᮍ , PWKH.LQJRIWKH1LJKW7LPH:RUOG.................................. 7 ᔓ䉏䉌䉏䈭䈇䈫ᗐ䈇 ............................................................................................................ 8 Memorable songs and memories I can’t forget. ................................................................... 9 ᖬϡњⱘ℠᳆ಲᖚ ....................................................................................................... 10 ᔓ䉏䉌䉏䈭䈇䈫ᕁ䈇 ............................................................................................................ 11 I’ll never forget that -

Fiesta De La Virgen De La Candelaria ("The Flame Virgin"): This Festival Lasts Two Weeks (The First Two Weeks of February), the Main Day Being the 2Nd

Peru (Sth. America) From a collection by Cassandra Ward for her Queen’s Guide. Fiesta de La Virgen de la Candelaria ("The flame Virgin"): This festival lasts two weeks (the first two weeks of February), the main day being the 2nd . Peru In Quechua is better known as the Mamacha Candicha. This is one of the great celebrations in Peru with beautiful dancers, many bands and people dancing in the street. This feast is celebrated in Puno (near the Titicaca lake) next to Bolivia, like many other feast this has been transculturated from an Inca feast through Catholicism. There are people dressed as SUPAYS (devils in Quechua) and dance "La diablada" ('The devil dance' in Spanish). You can also dance the Tuntuna (Like the KJARKAS's "Llorando se fue" theme that was copied for Kaoma in the Lambada), this rhythm is a soft mix of African and Andean tunes because of the presence of African slaves here who were working in the mines. Mamacha Candicha is the Puno's Patron, in the Catholic representation she is Jesus’s Mother, but she assumes almost all the devotion that Incas gave to the PACHA (earth). For this celebration comes bands from many sites, there are Bolivian groups too. The folk music from Puno is very rich. The groups and bands come here with their best dressings (multicolours, lighting and jingling), there are awards for the best. The mamacha candicha is taken in a "procession" and receives flowers, medals, lighting candles, prayers, songs and dances.... Food: Leche Asada (8-10 servings) · 1 can of sweetened, condensed milk · 1 can of evaporated milk · 1 cup sugar · 1 tsp vanilla extract · 8 eggs, beaten · 1/4 cup water Mix the condensed milk, evaporated milk, 1/2 cup of sugar, the vanilla, and eggs. -

Introducción

RESUMEN DE LOS PRINCIPALES RESULTADOS DEL TALLER “REPENSANDO LA CREATIVIDAD, EL RECONOCIMIENTO Y LO INDÍGENA”1 Coroico, 17-20 de Julio, 2012 INTRODUCCIÓN El grupo de trabajo Alta-PI (Alternativas a la Propiedad Intelectual) partió de la idea de que ciertas encrucijadas respecto a cuestiones de creatividad, reconocimiento y lo indígena, hasta ahora, no se han resuelto. ¿Cómo se debe reconocer la creatividad? y ¿cómo se debe tomar en cuenta el reconocimiento cuando se trata de comunidades o colectividades de creador@s y guardianes de conocimientos? Mucha gente alrededor del mundo ya ha respondido a estas preguntas a través de la implementación de la propiedad intelectual o enfocándose en las obras creativas como patrimonio intangible o inmaterial. L@s que han iniciado este proyecto creen que la sociedad civil boliviana podría estar en una posición única para empezar a desenredar estos nudos que cada vez más igualan la cultura con propiedad. Por las normas internacionales, una proporción muy alta de los bolivianos se auto identifican o son identificados por otros como indígenas, y desde comienzos del siglo XXI, el país ha estado viviendo procesos de cambio los cuales incluyen cambios a niveles constitucionales y jurídicos, como la creación de una nueva Constitución en el 2009. En este contexto, Alta-PI propone facilitar un amplio diálogo en la sociedad civil boliviana 1 Este taller y la difusión de sus resultados han sido posibles gracias al apoyo de la National Science Foundation (#1156260, Michelle Bigenho—PI, Henry Stobart—Co-PI; además de los ya mencionados, el equipo organizador también incluye a Juan Carlos Cordero, Bernardo Rozo, y Phoebe Smolin). -

Facultad Latinoamericana De Ciencias Sociales, FLACSO Ecuador Departamento De Antropología, Historia Y Humanidades Convocatoria 2014-2016

www.flacsoandes.edu.ec Facultad Latinoamericana de Ciencias Sociales, FLACSO Ecuador Departamento de Antropología, Historia y Humanidades Convocatoria 2014-2016 Tesis para obtener el título de maestría en Antropología Éxito, orgullo y vergüenza. Los usos de la cultura auténtica en la disputa por la música folclórica andina Adriana Soledad Aguilar Molina Asesor: Alfredo Santillán Lectoras: Mercedes Prieto y Alicia Torres Quito, mayo 2019 I Dedicatoria A mi familia, por ser la luz que guía mis pasos y no dejarme vencer en cada tropiezo A mi Jatari, el pequeño ser que me recuerda lo que realmente importa en esta vida Y a mi abuelita María Piedad, quien desde el cielo a todos nos cuida II Epígrafe “En el Conservatorio debía enseñarse música ecuatoriana, pero los eruditos que han estado al frente, tampoco se han acordado de la música nacional. Esto es por una cuestión social, porque se piensa que los que tocan música ecuatoriana son chagras, indígenas, entonces les dejan a un lado”. Gonzalo Benítez (1915-2005) Músico y compositor ecuatoriano III Tabla de contenidos Resumen ................................................................................................................................ VIII Agradecimientos ....................................................................................................................... IX Introducción ............................................................................................................................... 1 Capítulo 1 .................................................................................................................................. -

Los Kjarkas and the Diasporic Community on the Internet

Sari Pekkola Los Kjarkas and the Diasporic Community on the Internet No se acaba el mundo The world will not end cuando un amor se va when a loved one goes away no se acaba el mundo The world will not end y no se derrumbará and not be overthrown.41 This article examines questions of how elements of musical traditions are repro- duced in new social contexts, and what kind of music-making processes are in- volved when Los Kjarkas, an urban folk music group from Bolivia, encounters a diasporic community in Europe.42 Transnational experiences and opportunities for new forms of communication are significant for this urban folk music culture, which travels between places and spaces, as will be discussed in this article. This essay also focuses on the relationship between representations of Bolivian urban folk music and spaces where old and new meanings of identity and relationships are based on a sense of community. Aspects concerning relationships between Andean popular music, Latin American music and Bolivian folk music and their relationships to the audience are explored. Issues such as how relationships bet- ween a musical culture and a globally marginalised musical culture are articulated on the Internet, and new as well as old identities are also studied. Furthermore, issues about how cultural events are organised in diasporic formations and staged in new media relating to a tour in Europe will also be addressed. I will attempt to show how Los Kjarkas and Andean diasporic groups contribute to the construc- tion of a relationship between folk, popular, rural and urban music as well as a relationship between a local and a global scene. -

Antropología De Las Músicas Populares Mexicanas En Bolivia 11

ANTROPOLOGÍA DE LAS MÚSICAS POPULARES MEXICANAS EN BOLIVIA 11 ANTROPOLOGÍA DE LAS MÚSICAS POPULARES MEXICANAS EN BOLIVIA Luis Omar Montoya Arias Universidad Iberoamericana-León Miembro del Sistema Nacional de Investigadores RECIBIDO: 7 DE SEPTIEMBRE DE 2015; ACEPTADO: MARZO DE 2017 Abstract: In order to study Mexican popular music in Bolivia, it is necessary to understand the racial segregation that exists in this Latin American nation. Bolivian everydayness is di- vided into collas and cambas. Colla is derived from the name used by the Incas to name the people of his empire (Collao / Collasuyo); is a term that describes people as “Indians”. Cam- ba applies to the descendants of Europeans; Means peon of hacienda, foreman of Spaniards. The collas are the natives and the cambas are the mestizos. Both terms are pejorative, and since Juan Evo Morales Ayma, assumed the presidency of the Republic of Bolivia, in 2005, its use is considered racist and violating human rights. Key words; collas, cambas, altiplano, east, Vallegrande. Resumen: Para estudiar a las músicas populares mexicanas en Bolivia, es necesario compren- der la segregación racial que existe en esta nación latinoamericana. La cotidianeidad bolivia- na está dividida en collas y cambas. Colla se desprende del nombre que usaban los incas para nombrar a la gente de su imperio (collao/collasuyo); es un término que cataloga a las personas como “indios”. Camba se aplica a los descendientes de europeos; significa peón de hacienda, capataz de españoles. Los collas son los indígenas y los cambas los mestizos. Am- bos términos son peyorativos, y desde que Juan Evo Morales Ayma, asumió la presidencia de la República de Bolivia, en 2005, su uso se considera marcadamente racista. -

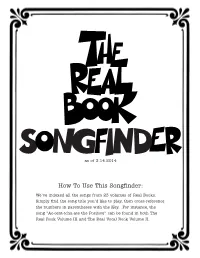

How to Use This Songfinder

as of 3.14.2014 How To Use This Songfinder: We’ve indexed all the songs from 23 volumes of Real Books. Simply find the song title you’d like to play, then cross-reference the numbers in parentheses with the Key. For instance, the song “Ac-cent-tchu-ate the Positive” can be found in both The Real Book Volume III and The Real Vocal Book Volume II. KEY Unless otherwise marked, books are for C instruments. For more product details, please visit www.halleonard.com/realbook. 01. The Real Book – Volume I 08. The Real Blues Book/00240264 C Instruments/00240221 09. Miles Davis Real Book/00240137 B Instruments/00240224 Eb Instruments/00240225 10. The Charlie Parker Real Book/00240358 BCb Instruments/00240226 11. The Duke Ellington Real Book/00240235 Mini C Instruments/00240292 12. The Bud Powell Real Book/00240331 Mini B Instruments/00240339 CD-ROMb C Instruments/00451087 13. The Real Christmas Book C Instruments with Play-Along Tracks C Instruments/00240306 Flash Drive/00110604 B Instruments/00240345 Eb Instruments/00240346 02. The Real Book – Volume II BCb Instruments/00240347 C Instruments/00240222 B Instruments/00240227 14. The Real Rock Book/00240313 Eb Instruments/00240228 15. The Real Rock Book – Volume II/00240323 BCb Instruments/00240229 16. The Real Tab Book – Volume I/00240359 Mini C Instruments/00240293 CD-ROM C Instruments/00451088 17. The Real Bluegrass Book/00310910 03. The Real Book – Volume III 18. The Real Dixieland Book/00240355 C Instruments/00240233 19. The Real Latin Book/00240348 B Instruments/00240284 20. The Real Worship Book/00240317 Eb Instruments/00240285 BCb Instruments/00240286 21. -

An Ethnomusicological Study of the Globalization of the Quena in Andean Music and the World

An ethnomusicological study of the globalization of the quena in Andean music and the world by Galo C. Bustamante A THESIS submitted to Oregon State University Honors College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Honors Baccalaureate of Science in Biology (Honors Scholar) Presented May 18, 2021 Commencement June 2021 AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Galo C. Bustamante for the degree of Honors Baccalaureate of Science in Biology presented on May 18, 2021. Title: An ethnomusicological study of the globalization of the quena in Andean music and the world. Abstract approved:_____________________________________________________ Eric Hill This ethnomusicological study has examined the forces that have globalized the Andean instrument of the quena and the genre of Andean music as a whole. This thesis specifically addresses the cultural, and socio-political factors over the last century that has led to the quena being circulated across the globe. Much ethnographic fieldwork, and many historical accounts have been published; this thesis takes many of those works and compiles the knowledge into one unified work which tracks the movement of the quena. This was accomplished through review of the existing primary literature and compiling the relevant knowledge into one cohesive body of text. The primary findings show that there have been three waves of spread or globalization: 1) spread from urban migration fueled by Peruvian indigenista movements, 2) a cultural explosion of folkloric interests in cosmopolitan centers such as Buenos Aires and Paris, 3) politicization of the music and a folk revitalization which brought Andean music to the forefront in the 1960’s through the 1980’s in Chile and the United States.