8515-8904-1-PB.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The La Solidaridad and Philippine Journalism in Spain (1889-1895)

44 “Our Little Newspaper”… “OUR LITTLE NEWSPAPER” THE LA SOLIDARIDAD AND PHILIPPINE JOURNALISM IN SPAIN (1889-1895) Jose Victor Z. Torres, PhD De La Salle University-Manila [email protected] “Nuestros periodiquito” or “Our little newspaper” Historian, archivist, and writer Manuel Artigas y was how Marcelo del Pilar described the periodical Cuerva had written works on Philippine journalism, that would serve as the organ of the Philippine especially during the celebration of the tercentenary reform movement in Spain. For the next seven years, of printing in 1911. A meticulous researcher, Artigas the La Solidaridad became the respected Philippine newspaper in the peninsula that voiced out the viewed and made notes on the pre-war newspaper reformists’ demands and showed their attempt to collection in the government archives and the open the eyes of the Spaniards to what was National Library. One of the bibliographical entries happening to the colony in the Philippines. he wrote was that of the La Solidaridad, which he included in his work “El Centenario de la Imprenta”, But, despite its place in our history, the story of a series of articles in the American period magazine the La Solidaridad has not entirely been told. Madalas Renacimiento Filipino which ran from 1911-1913. pag-usapan pero hindi alam ang kasaysayan. We do not know much of the La Solidaridad’s beginnings, its Here he cited a published autobiography by reformist struggle to survive as a publication, and its sad turned revolutionary supporter, Timoteo Paez as his ending. To add to the lacunae of information, there source. -

Province, City, Municipality Total and Barangay Population AURORA

2010 Census of Population and Housing Aurora Total Population by Province, City, Municipality and Barangay: as of May 1, 2010 Province, City, Municipality Total and Barangay Population AURORA 201,233 BALER (Capital) 36,010 Barangay I (Pob.) 717 Barangay II (Pob.) 374 Barangay III (Pob.) 434 Barangay IV (Pob.) 389 Barangay V (Pob.) 1,662 Buhangin 5,057 Calabuanan 3,221 Obligacion 1,135 Pingit 4,989 Reserva 4,064 Sabang 4,829 Suclayin 5,923 Zabali 3,216 CASIGURAN 23,865 Barangay 1 (Pob.) 799 Barangay 2 (Pob.) 665 Barangay 3 (Pob.) 257 Barangay 4 (Pob.) 302 Barangay 5 (Pob.) 432 Barangay 6 (Pob.) 310 Barangay 7 (Pob.) 278 Barangay 8 (Pob.) 601 Calabgan 496 Calangcuasan 1,099 Calantas 1,799 Culat 630 Dibet 971 Esperanza 458 Lual 1,482 Marikit 609 Tabas 1,007 Tinib 765 National Statistics Office 1 2010 Census of Population and Housing Aurora Total Population by Province, City, Municipality and Barangay: as of May 1, 2010 Province, City, Municipality Total and Barangay Population Bianuan 3,440 Cozo 1,618 Dibacong 2,374 Ditinagyan 587 Esteves 1,786 San Ildefonso 1,100 DILASAG 15,683 Diagyan 2,537 Dicabasan 677 Dilaguidi 1,015 Dimaseset 1,408 Diniog 2,331 Lawang 379 Maligaya (Pob.) 1,801 Manggitahan 1,760 Masagana (Pob.) 1,822 Ura 712 Esperanza 1,241 DINALUNGAN 10,988 Abuleg 1,190 Zone I (Pob.) 1,866 Zone II (Pob.) 1,653 Nipoo (Bulo) 896 Dibaraybay 1,283 Ditawini 686 Mapalad 812 Paleg 971 Simbahan 1,631 DINGALAN 23,554 Aplaya 1,619 Butas Na Bato 813 Cabog (Matawe) 3,090 Caragsacan 2,729 National Statistics Office 2 2010 Census of Population and -

The Development of the Philippine Foreign Service

The Development of the Philippine Foreign Service During the Revolutionary Period and the Filipino- American War (1896-1906): A Story of Struggle from the Formation of Diplomatic Contacts to the Philippine Republic Augusto V. de Viana University of Santo Tomas The Philippine foreign service traces its origin to the Katipunan in the early 1890s. Revolutionary leaders knew that the establishment of foreign contacts would be vital to the success of the objectives of the organization as it struggles toward the attainment of independence. This was proven when the Katipunan leaders tried to secure the support of Japanese and German governments for a projected revolution against Spain. Some patriotic Filipinos in Hong Kong composed of exiles also supported the Philippine Revolution.The organization of these exiled Filipinos eventually formed the nucleus of the Philippine Central Committee, which later became known as the Hong Kong Junta after General Emilio Aguinaldo arrived there in December 1897. After Aguinaldo returned to the Philippines in May 1898, he issued a decree reorganizing his government and creating four departments, one of which was the Department of Foreign Relations, Navy, and Commerce. This formed the basis of the foundation of the present Department of Foreign Affairs. Among the roles of this office was to seek recognition from foreign countries, acquire weapons and any other needs of the Philippine government, and continue lobbying for support from other countries. It likewise assigned emissaries equivalent to today’s ambassadors and monitored foreign reactions to the developments in the Philippines. The early diplomats, such as Felipe Agoncillo who was appointed as Minister Plenipotentiary of the revolutionary government, had their share of hardships as they had to make do with meager means. -

COMPLETION REPORT Images of Japan in Filipino Spanish-Language Newspapers, 1900-1910 Dr

COMPLETION REPORT Images of Japan in Filipino Spanish-Language Newspapers, 1900-1910 Dr. Wystan de la Peña Department of European Languages College of Arts and Letters University of the Philippines Diliman Images of Japan in Filipino Spanish Language Newspapers, 1900-1910 is a study on the representations of Japan found in select Spanish-language newspapers during the first decade of American colonial rule. It is also the period when Spanish-era educated Filipino intellectuals -- the generation which fought the revolutionary wars against Spain (1896-1898) and America (1899-1901) -- looked at Japan as a model of an Asian nation they would like the Philippines to be. The research revealed perspectives not usually found in primary materials accessed by non-Spanish-reading Filipino historians. Articles from La Solidaridad, the Filipino reformists' organ showed favorable representations of Japan. Japan’s emergence as a regional power was capitalized by the Katipunan, the independence movement founded in 1892, when it misled Spanish authorities into thinking that Tokyo had a stake in the anti-Spain revolution by making it appear that their newspaper, Ang Kalayaan, was being published in Yokohama. During the war with the United States, the Philippine government sent Mariano Ponce as diplomatic representative to Yokohama. Ponce’s correspondence with leading Japanese figures documents his insightful observations on Japanese culture. Ponce eventually married a Japanese woman. During the American colonial period, Fil-hispanic literary production, which first came out in newspapers, projected images of Japan as a model Asian country to be emulated by a nascent Philippine polity. This is seen particularly in the works of Jesus Balmori and published speeches of T.H. -

One Big File

MISSING TARGETS An alternative MDG midterm report NOVEMBER 2007 Missing Targets: An Alternative MDG Midterm Report Social Watch Philippines 2007 Report Copyright 2007 ISSN: 1656-9490 2007 Report Team Isagani R. Serrano, Editor Rene R. Raya, Co-editor Janet R. Carandang, Coordinator Maria Luz R. Anigan, Research Associate Nadja B. Ginete, Research Assistant Rebecca S. Gaddi, Gender Specialist Paul Escober, Data Analyst Joann M. Divinagracia, Data Analyst Lourdes Fernandez, Copy Editor Nanie Gonzales, Lay-out Artist Benjo Laygo, Cover Design Contributors Isagani R. Serrano Ma. Victoria R. Raquiza Rene R. Raya Merci L. Fabros Jonathan D. Ronquillo Rachel O. Morala Jessica Dator-Bercilla Victoria Tauli Corpuz Eduardo Gonzalez Shubert L. Ciencia Magdalena C. Monge Dante O. Bismonte Emilio Paz Roy Layoza Gay D. Defiesta Joseph Gloria This book was made possible with full support of Oxfam Novib. Printed in the Philippines CO N T EN T S Key to Acronyms .............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................. iv Foreword.................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... vii The MDGs and Social Watch -

Producing Rizal: Negotiating Modernity Among the Filipino Diaspora in Hawaii

PRODUCING RIZAL: NEGOTIATING MODERNITY AMONG THE FILIPINO DIASPORA IN HAWAII A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN ASIAN STUDIES AUGUST 2014 By Ai En Isabel Chew Thesis Committee: Patricio Abinales, Chairperson Cathryn Clayton Vina Lanzona Keywords: Filipino Diaspora, Hawaii, Jose Rizal, Modernity, Rizalista Sects, Knights of Rizal 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements……………………………………………………………………..…5 Chapter 1 Introduction: Rizal as a Site of Contestation………………………………………………………………………………………....6 Methodology ..................................................................................................................18 Rizal in the Filipino Academic Discourse......................................................................21 Chapter 2 Producing Rizal: Interactions on the Trans-Pacific Stage during the American Colonial Era,1898-1943…………………………..………………………………………………………...29 Rizal and the Philippine Revolution...............................................................................33 ‘Official’ Productions of Rizal under American Colonial Rule .....................................39 Rizal the Educated Cosmopolitan ..................................................................................47 Rizal as the Brown Messiah ...........................................................................................56 Conclusion ......................................................................................................................66 -

Philippine History and Government

Remembering our Past 1521 – 1946 By: Jommel P. Tactaquin Head, Research and Documentation Section Veterans Memorial and Historical Division Philippine Veterans Affairs Office The Philippine Historic Past The Philippines, because of its geographical location, became embroiled in what historians refer to as a search for new lands to expand European empires – thinly disguised as the search for exotic spices. In the early 1400’s, Portugese explorers discovered the abundance of many different resources in these “new lands” heretofore unknown to early European geographers and explorers. The Portugese are quickly followed by the Dutch, Spaniards, and the British, looking to establish colonies in the East Indies. The Philippines was discovered in 1521 by Portugese explorer Ferdinand Magellan and colonized by Spain from 1565 to 1898. Following the Spanish – American War, it became a territory of the United States. On July 4, 1946, the United States formally recognized Philippine independence which was declared by Filipino revolutionaries from Spain. The Philippine Historic Past Although not the first to set foot on Philippine soil, the first well document arrival of Europeans in the archipelago was the Spanish expedition led by Portuguese Ferdinand Magellan, which first sighted the mountains of Samara. At Masao, Butuan, (now in Augustan del Norte), he solemnly planted a cross on the summit of a hill overlooking the sea and claimed possession of the islands he had seen for Spain. Magellan befriended Raja Humabon, the chieftain of Sugbu (present day Cebu), and converted him to Catholicism. After getting involved in tribal rivalries, Magellan, with 48 of his men and 1,000 native warriors, invaded Mactan Island. -

FILIPINOS in HISTORY Published By

FILIPINOS in HISTORY Published by: NATIONAL HISTORICAL INSTITUTE T.M. Kalaw St., Ermita, Manila Philippines Research and Publications Division: REGINO P. PAULAR Acting Chief CARMINDA R. AREVALO Publication Officer Cover design by: Teodoro S. Atienza First Printing, 1990 Second Printing, 1996 ISBN NO. 971 — 538 — 003 — 4 (Hardbound) ISBN NO. 971 — 538 — 006 — 9 (Softbound) FILIPINOS in HIS TOR Y Volume II NATIONAL HISTORICAL INSTITUTE 1990 Republic of the Philippines Department of Education, Culture and Sports NATIONAL HISTORICAL INSTITUTE FIDEL V. RAMOS President Republic of the Philippines RICARDO T. GLORIA Secretary of Education, Culture and Sports SERAFIN D. QUIASON Chairman and Executive Director ONOFRE D. CORPUZ MARCELINO A. FORONDA Member Member SAMUEL K. TAN HELEN R. TUBANGUI Member Member GABRIEL S. CASAL Ex-OfficioMember EMELITA V. ALMOSARA Deputy Executive/Director III REGINO P. PAULAR AVELINA M. CASTA/CIEDA Acting Chief, Research and Chief, Historical Publications Division Education Division REYNALDO A. INOVERO NIMFA R. MARAVILLA Chief, Historic Acting Chief, Monuments and Preservation Division Heraldry Division JULIETA M. DIZON RHODORA C. INONCILLO Administrative Officer V Auditor This is the second of the volumes of Filipinos in History, a com- pilation of biographies of noted Filipinos whose lives, works, deeds and contributions to the historical development of our country have left lasting influences and inspirations to the present and future generations of Filipinos. NATIONAL HISTORICAL INSTITUTE 1990 MGA ULIRANG PILIPINO TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Lianera, Mariano 1 Llorente, Julio 4 Lopez Jaena, Graciano 5 Lukban, Justo 9 Lukban, Vicente 12 Luna, Antonio 15 Luna, Juan 19 Mabini, Apolinario 23 Magbanua, Pascual 25 Magbanua, Teresa 27 Magsaysay, Ramon 29 Makabulos, Francisco S 31 Malabanan, Valerio 35 Malvar, Miguel 36 Mapa, Victorino M. -

Scientific Authority, Nationalism, and Colonial Entanglements Between Germany, Spain, and the Philippines, 1850 to 1900

Scientific Authority, Nationalism, and Colonial Entanglements between Germany, Spain, and the Philippines, 1850 to 1900 Nathaniel Parker Weston A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2012 Reading Committee: Uta G. Poiger, Chair Vicente L. Rafael Lynn Thomas Program Authorized to Offer Degree: History ©Copyright 2012 Nathaniel Parker Weston University of Washington Abstract Scientific Authority, Nationalism, and Colonial Entanglements between Germany, Spain, and the Philippines, 1850 to 1900 Nathaniel Parker Weston Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Professor Uta G. Poiger This dissertation analyzes the impact of German anthropology and natural history on colonialism and nationalism in Germany, Spain, the Philippines, and the United States during the second half of the nineteenth-century. In their scientific tracts, German authors rehearsed the construction of racial categories among colonized peoples in the years prior to the acquisition of formal colonies in Imperial Germany and portrayed their writings about Filipinos as superior to all that had been previously produced. Spanish writers subsequently translated several German studies to promote continued economic exploitation of the Philippines and uphold notions of Spaniards’ racial supremacy over Filipinos. However, Filipino authors also employed the translations, first to demand colonial reform and to examine civilizations in the Philippines before and after the arrival of the Spanish, and later to formulate nationalist arguments. By the 1880s, the writings of Filipino intellectuals found an audience in newly established German scientific associations, such as the German Society for Anthropology, Ethnology, and Prehistory, and German-language periodicals dealing with anthropology, ethnology, geography, and folklore. -

Philippine Masonry to 1890 the Masonic Lodges Served As

PHILIPPINE MASONRY TO 1890 JOHN N. SCHUMACHER, S.J. THE MASONIC LODGES SERVED AS CENTERS FOR MANY OF the Liberal conspiracies in Spain against clerical and reactionary governments during the first three-quarters of the nineteenth century, 1 and Masonry played a considerable part in the emancipation of the Spanish-American republics.2 In Cuba, too, Masonic influence was strong in the insurrections of the second half of the nineteenth century.3 It might be expected then, that in a society far more theocratic in nature than those mentioned - as was the nineteenth century Philippines - that Masonry would play a considerable role in any nationalist movement. This was because of its anti-clerical orientation and because of the opportunity its secrecy allowed for clandestine activity. It is a fact that almost every Filipino nationalist leader of the Propaganda Period was at one time or another a Mason. But the role of Masonry in the nation alist movement and in the Revolution which followed it, has, it seems, fre quently been exaggerated and misinterpreted by the friends of Masonry as well as by its enemies. Particularly the writing of the Friars and Jesuits of the Revolutionary period (both published works and private correspond ence) are wont to see Masons in every corner.4 Books have not been lacking, 1 See Antonio Ballesteros y Beretta, Historia de Espa1ia y su influeneia en la historia universal (2nd ed.; Barcelona: Salvat, 1943 ff.), X, 183-184; Gerald Brenan, Spanish Labyrinth (2nd ed.; Cambridge: University Press, 1950), 206-208. Books such as Eduardo Comin Colomer, La Masoneria .en Espana (Apuntes para una interpretacion mas6nica de la historia patria) (Madrid: Editora Nacional, 1944) and the annotated edition by Mauricio Carlavilla of Miguel Morayta's M asoneria ~spanola. -

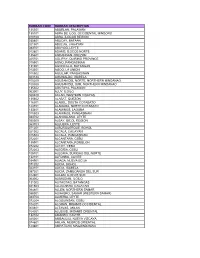

Rurban Code Rurban Description 135301 Aborlan

RURBAN CODE RURBAN DESCRIPTION 135301 ABORLAN, PALAWAN 135101 ABRA DE ILOG, OCCIDENTAL MINDORO 010100 ABRA, ILOCOS REGION 030801 ABUCAY, BATAAN 021501 ABULUG, CAGAYAN 083701 ABUYOG, LEYTE 012801 ADAMS, ILOCOS NORTE 135601 AGDANGAN, QUEZON 025701 AGLIPAY, QUIRINO PROVINCE 015501 AGNO, PANGASINAN 131001 AGONCILLO, BATANGAS 013301 AGOO, LA UNION 015502 AGUILAR, PANGASINAN 023124 AGUINALDO, ISABELA 100200 AGUSAN DEL NORTE, NORTHERN MINDANAO 100300 AGUSAN DEL SUR, NORTHERN MINDANAO 135302 AGUTAYA, PALAWAN 063001 AJUY, ILOILO 060400 AKLAN, WESTERN VISAYAS 135602 ALABAT, QUEZON 116301 ALABEL, SOUTH COTABATO 124701 ALAMADA, NORTH COTABATO 133401 ALAMINOS, LAGUNA 015503 ALAMINOS, PANGASINAN 083702 ALANGALANG, LEYTE 050500 ALBAY, BICOL REGION 083703 ALBUERA, LEYTE 071201 ALBURQUERQUE, BOHOL 021502 ALCALA, CAGAYAN 015504 ALCALA, PANGASINAN 072201 ALCANTARA, CEBU 135901 ALCANTARA, ROMBLON 072202 ALCOY, CEBU 072203 ALEGRIA, CEBU 106701 ALEGRIA, SURIGAO DEL NORTE 132101 ALFONSO, CAVITE 034901 ALIAGA, NUEVA ECIJA 071202 ALICIA, BOHOL 023101 ALICIA, ISABELA 097301 ALICIA, ZAMBOANGA DEL SUR 012901 ALILEM, ILOCOS SUR 063002 ALIMODIAN, ILOILO 131002 ALITAGTAG, BATANGAS 021503 ALLACAPAN, CAGAYAN 084801 ALLEN, NORTHERN SAMAR 086001 ALMAGRO, SAMAR (WESTERN SAMAR) 083704 ALMERIA, LEYTE 072204 ALOGUINSAN, CEBU 104201 ALORAN, MISAMIS OCCIDENTAL 060401 ALTAVAS, AKLAN 104301 ALUBIJID, MISAMIS ORIENTAL 132102 AMADEO, CAVITE 025001 AMBAGUIO, NUEVA VIZCAYA 074601 AMLAN, NEGROS ORIENTAL 123801 AMPATUAN, MAGUINDANAO 021504 AMULUNG, CAGAYAN 086401 ANAHAWAN, SOUTHERN LEYTE -

Preparatory Survey for Expressway Projects in Mega Manila Region

REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC WORKS AND HIGHWAYS (DPWH) PREPARATORY SURVEY FOR EXPRESSWAY PROJECTS IN MEGA MANILA REGION CENTRAL LUZON LINK EXPRESSWAY PROJECT (Phase I) FINAL REPORT MAIN TEXT NOVEMBER 2012 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY (JICA) CTI ENGINEERING INTERNATIONAL CO., LTD MITSUBISHI RESEARCH INSTITUTE, INC. ORIENTAL CONSULTANTS CO., LTD EI METROPOLITAN EXPRESSWAY CO., LTD CR(3) 12-145(1) CLLEX EXCHANGE RATE July 2011 1PhP= 1.86 Japan Yen 1US$=43.7Philippine Peso 1US$= 81.2 Japan Yen Central Bank of the Philippines TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary 1. BACKGROUND OF THE CLLEX PROJECT.............................................................................................. S-1 2. NECESSITY OF THE CLLEX PROJECT .................................................................................................... S-2 3. OBJECTIVE OF THE CLLEX PROJECT..................................................................................................... S-2 4. TRAFFIC DEMAND FORECAST ................................................................................................................ S-2 4.1. Existing Traffic Condition....................................................................................................................... S-2 4.2. Future Traffic Volume on CLLEX PHASE-1 Section ............................................................................ S-6 5. REVIEW OF 2010 FEASIBILITY STUDY OF CLLEX PHASE-1............................................................ S-10 5.1. Technical