Monetary Policy, Economic Order and Divergence Forces in the European Union

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2019 European Elections the Weight of the Electorates Compared to the Electoral Weight of the Parliamentary Groups

2019 European Elections The weight of the electorates compared to the electoral weight of the parliamentary groups Guillemette Lano Raphaël Grelon With the assistance of Victor Delage and Dominique Reynié July 2019 2019 European Elections. The weight of the electorates | Fondation pour l’innovation politique I. DISTINGUISHING BETWEEN THE WEIGHT OF ELECTORATES AND THE ELECTORAL WEIGHT OF PARLIAMENTARY GROUPS The Fondation pour l’innovation politique wished to reflect on the European elections in May 2019 by assessing the weight of electorates across the European constituency independently of the electoral weight represented by the parliamentary groups comprised post-election. For example, we have reconstructed a right-wing Eurosceptic electorate by aggregating the votes in favour of right-wing national lists whose discourses are hostile to the European Union. In this case, for instance, this methodology has led us to assign those who voted for Fidesz not to the European People’s Party (EPP) group but rather to an electorate which we describe as the “populist right and extreme right” in which we also include those who voted for the Italian Lega, the French National Rally, the Austrian FPÖ and the Sweden Democrats. Likewise, Slovak SMER voters were detached from the Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats (S&D) Group and instead categorised as part of an electorate which we describe as the “populist left and extreme left”. A. The data collected The electoral results were collected list by list, country by country 1, from the websites of the national parliaments and governments of each of the States of the Union. We then aggregated these data at the European level, thus obtaining: – the number of individuals registered on the electoral lists on the date of the elections, or the registered voters; – the number of votes, or the voters; – the number of valid votes in favour of each of the lists, or the votes cast; – the number of invalid votes, or the blank or invalid votes. -

It-Tlettax-Il Leġiżlatura Pl

IT-TLETTAX-IL LEĠIŻLATURA P.L. 730 Dokument imqiegħed fuq il-Mejda tal-Kamra tad-Deputati fis-Seduta Numru 55 tal-21 ta’ Novembru 2017 mid-Deputat Prim Ministru u Ministru għas-Saħħa, f’isem il-Prim Ministru. ___________________________ Raymond Scicluna Skrivan tal-Kamra ANNUAL REPORT 2016 Published in 2017 by the Broadcasting Authority 7 Mile End Road Ħamrun HMR 1718 Malta Compiled, produced and designed by: Mario Axiak B.A. Hons (Business Management), M.B.A. (Maastricht) Head Research & Communications The Hon. Dr Joseph Muscat KUOM, Ph.D., M.P Prime Minister Office of the Prime Minister Auberge De Castille Valletta June 2017 Honourable Prime Minister, Broadcasting Authority Annual Report 2016 In accordance with sub-article (1) of article 30 of the Broadcasting Act, Chapter 350 of the Laws of Malta, we have pleasure in forwarding the Broadcasting Authority’s Annual Report for 2016. Yours sincerely, ______________________________ ______________________________ Ms Tanya Borg Cardona Dr Joanna Spiteri Chairperson Chief Executive BROADCASTING AUTHORITY MALTA ANNUAL REPORT 2016 CONTENTS 1. Review of the Year 7 1.1 The Broadcasting Authority 7 1.2 Għargħur Transmitting Facilities 7 1.3 Sponsorship - Certificate Course in Proof Reading 7 1.4 Sponsorship - Malta Journalism Awards 8 1.5 Thematic Reports compiled by the Monitoring Department 8 1.6 Reach-out 8 1.7 Political Broadcasts 9 1.8 Equality Certification 9 1.9 Wear it Pink 9 2. Administrative Offences 11 3. Broadcasting Licences 13 3.1 Radio Broadcasting Licences 13 3.1.1 Community Radio Stations 13 3.1.2 Drive-In Cinema Event 13 3.1.3 Nationwide Analogue Radio (FM/AM) 13 3.1.4 Digital Radio Platform 13 3.1.5 Request for a Medium Wave Radio Station 13 3.2 Nationwide Television and Satellite Stations 13 3.2.1 Television Stations 13 3.2.2 Satellite Licences 15 4. -

It-Tlettax-Il Leġiżlatura Pl 2001

IT-TLETTAX-IL LEĠIŻLATURA P.L. 2001 Dokument imqiegħed fuq il-Mejda tal-Kamra tad-Deputati fis-Seduta Numru 138 tal-1 ta’ Ottubru 2018 mill-Ispeaker, l-Onor. Anġlu Farrugia. ___________________________ Raymond Scicluna Skrivan tal-Kamra 12th Conference of Presidents of Parliaments of Small European States 19-21 September 2018 Vaduz, Liechtenstein Hon Anglu Farrugia, Speaker Parliamentary Delegation Report to the House of Representatives. Date: 19-21 th September 2018 Venue: Vaduz, Liechtenstein Maltese delegation: Honourable Anglu Farrugia, President of the House of Representatives Programme: At the invitation of the President of Parliament of the Principality of Liechtenstein, Honourable Albert Frick, the Speaker of the House of Representatives, Parliament of Malta, Honourable Anglu Farrugia, was invited to participate at the 12th Conference of Presidents of Parliaments of Small European States. Participation of Speaker Anglu Farrugia at the 12th Conference of the Presidents of Parliaments of Small European States in Liechtenstein, held between the 19th and the 21st of September 2018 Between the 19th and the 21st September, I attended the 12th Conference of the Presidents of Parliaments of Small European States. The official opening was held on the 19th of September and we were welcomed by the President of the Landtag, Mr Albert Frick, who is the Speaker of the House of Representatives of Liechtenstein, Vaduz. The following day, at around 8 a.m., there was the opening of the Conference and the first session was entitled "The sovereignty of small states: origins and international recognition. The introductory speech was made by Dr Christian Frommelt, Director of the Liechtenstein Institute, who was then followed by interventions from the Speakers of Andorra, Cyprus, Iceland, Liechtenstein, Luxemburg, Malta, Monaco, Montenegro and San Marino. -

Review of European and National Election Results 2014-2019 Mid-Term January 2017

Review of European and National Election Results 2014-2019 Mid-term January 2017 STUDY Public Opinion Monitoring Series Directorate-General for Communication Published by EPRS | European Parliamentary Research Service Author: Jacques Nancy, Public Opinion Monitoring Unit PE 599.242 Directorate-General for Communication Public Opinion Monitoring Unit REVIEW EE2014 Edition Spéciale Mi-Législature Special Edition on Mid-term Legislature LES ÉLECTIONS EUROPÉENNES ET NATIONALES EN CHIFFRES EUROPEAN AND NATIONAL ELECTIONS RESULTS TABLES Mise à jour – 20 janvier 2017 Update – 20th January 2017 8éme Législature 8th Parliamentary Term DANS CETTE EDITION Page IN THIS EDITION Page EDITORIAL11 EDITORIAL I.COMPOSITION DU PARLEMENT EUROPÉEN 6 I. COMPOSITION OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT 6 A.REPARTITION DES SIEGES 7 A.DISTRIBUTION OF SEATS 7 B.COMPOSITION DU PARLEMENT 8 B.COMPOSITION OF THE PARLIAMENT 8 -9-9AU 01/07/2014 ON THE 01/07/2014 -10-10AU 20/01/2017 ON THE 20/01/2017 C.SESSIONS CONSTITUTIVES ET PARLEMENT 11 C.CONSTITUTIVE SESSIONS AND OUTGOING EP 11 SORTANT DEPUIS 1979 SINCE 1979 D.REPARTITION FEMMES - HOMMES 29 D.PROPORTION OF WOMEN AND MEN 29 AU 20/01/2017 ON 20/01/2017 -30-30PAR GROUPE POLITIQUE AU 20/01/2017 IN THE POLITICAL GROUPS ON 20/01/2017 ET DEPUIS 1979 AND SINCE 1979 E.PARLEMENTAIRES RÉÉLUS 33 E.RE-ELECTED MEMBERS OF PARLIAMENT 33 II.NOMBRE DE PARTIS NATIONAUX AU PARLEMENT 35 II.NUMBER OF NATIONAL PARTIES IN THE EUROPEAN 35 EUROPEEN AU 20/01/2017 PARLIAMENT ON 20/01/2017 III.TAUX DE PARTICIPATION 37 III. TURNOUT 37 -38-38TAUX DE PARTICIPATION -

Review of European and National Election Results Update: September 2019

REVIEW OF EUROPEAN AND NATIONAL ELECTION RESULTS UPDATE: SEPTEMBER 2019 A Public Opinion Monitoring Publication REVIEW OF EUROPEAN AND NATIONAL ELECTION RESULTS UPDATE: SEPTEMBER 2019 Directorate-General for Communication Public Opinion Monitoring Unit May 2019 - PE 640.149 IMPRESSUM AUTHORS Philipp SCHULMEISTER, Head of Unit (Editor) Alice CHIESA, Marc FRIEDLI, Dimitra TSOULOU MALAKOUDI, Matthias BÜTTNER Special thanks to EP Liaison Offices and Members’ Administration Unit PRODUCTION Katarzyna ONISZK Manuscript completed in September 2019 Brussels, © European Union, 2019 Cover photo: © Andrey Kuzmin, Shutterstock.com ABOUT THE PUBLISHER This paper has been drawn up by the Public Opinion Monitoring Unit within the Directorate–General for Communication (DG COMM) of the European Parliament. To contact the Public Opinion Monitoring Unit please write to: [email protected] LINGUISTIC VERSION Original: EN DISCLAIMER This document is prepared for, and primarily addressed to, the Members and staff of the European Parliament to assist them in their parliamentary work. The content of the document is the sole responsibility of its author(s) and any opinions expressed herein should not be taken to represent an official position of the Parliament. TABLE OF CONTENTS EDITORIAL 1 1. COMPOSITION OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT 5 DISTRIBUTION OF SEATS OVERVIEW 1979 - 2019 6 COMPOSITION OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT LAST UPDATE (31/07/2019) 7 CONSTITUTIVE SESSION (02/07/2019) AND OUTGOING EP SINCE 1979 8 PROPORTION OF WOMEN AND MEN PROPORTION - LAST UPDATE 02/07/2019 28 PROPORTIONS IN POLITICAL GROUPS - LAST UPDATE 02/07/2019 29 PROPORTION OF WOMEN IN POLITICAL GROUPS - SINCE 1979 30 2. NUMBER OF NATIONAL PARTIES IN THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT CONSTITUTIVE SESSION 31 3. -

Ben Nasan Khaled Ibrahim Pen Vs. Minister of Health, Etc. B

Notes in Preparation for Testimony in A) Court Case No. 395/2017: Ben Nasan Khaled Ibrahim Pen vs. Minister of Health, etc. B) Court Case No. 220/2016: Gafà Neville vs. Lindsay David C) Court Case No. 221/2016: Gafà Neville vs. Lindsay David These notes contain a summary of the assertions, evidence and testimony relating to the allegations that there have been illicit sales of Schengen Visas at the Maltese Consulate in Tripoli and in the issuance of Humanitarian Medical Visas by persons in the Office of the Maltese Prime Minister. If the allegations are correct, then corrupt officials have issued up to 88,000 Schengen Visas and an unknown number of Medical Visas, permitting an inflow in to the European Union of persons that could be potential security threats and/or illegal migrants. Furthermore, there are indications that persons that should have been entitled to Medical Visas free of charge might have been forced to pay for them or, in some cases not been able to access healthcare that under government agreements were guaranteed. The scheme, if the assertions prove to be correct, has netted the persons involved millions of euros. 1 TABLE OF CONTENT BACKGROUND ................................................................................................................................................. 4 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................................... 6 THE THREE LIBEL CASES .................................................................................................................................... -

Republic of Malta

Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights REPUBLIC OF MALTA EARLY PARLIAMENTARY ELECTIONS 3 June 2017 OSCE/ODIHR Election Assessment Mission Final Report Warsaw 9 October 2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...................................................................................................... 1 II. INTRODUCTION AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ........................................................... 3 III. BACKGROUND AND POLITICAL CONTEXT ................................................................. 3 IV. LEGAL FRAMEWORK ......................................................................................................... 4 V. ELECTORAL SYSTEM .......................................................................................................... 5 VI. ELECTION ADMINISTRATION .......................................................................................... 6 VII. VOTER REGISTRATION ...................................................................................................... 7 VIII. CANDIDATE REGISTRATION ............................................................................................ 8 IX. CAMPAIGN .............................................................................................................................. 9 X. POLITICAL PARTY AND CAMPAIGN FINANCE ......................................................... 11 A. DONATIONS AND EXPENDITURE ............................................................................................... 11 B. OVERSIGHT, REPORTING -

Of European and National Election Results Update: September 2018

REVIEW OF EUROPEAN AND NATIONAL ELECTION RESULTS UPDATE: SEPTEMBER 2018 A Public Opinion Monitoring Publication REVIEW OF EUROPEAN AND NATIONAL ELECTION RESULTS UPDATE: SEPTEMBER 2018 Directorate-General for Communication Public Opinion Monitoring Unit September 2018 - PE 625.195 TABLE OF CONTENTS EDITORIAL 1 1. COMPOSITION OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT 5 DISTRIBUTION OF SEATS EE2019 6 OVERVIEW 1979 - 2014 7 COMPOSITION OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT LAST UPDATE (10/09/2018) 8 CONSTITUTIVE SESSION (01/07/2014) 9 PROPORTION OF WOMEN AND MEN PROPORTION - LAST UPDATE 10 PROPORTIONS IN POLITICAL GROUPS - LAST UPDATE 11 PROPORTION OF WOMEN IN POLITICAL GROUPS - SINCE 1979 12 2. NUMBER OF NATIONAL PARTIES IN THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT 13 3. TURNOUT: EE2014 15 TURNOUT IN THE LAST EUROPEAN AND NATIONAL ELECTIONS 16 TURNOUT IN THE EE2014 18 TURNOUT COMPARISON: 2009 (2013) - 2014 19 TURNOUT IN THE EE2014 - BREAKDOWN BY GENDER 20 TURNOUT IN THE EE2014 - BREAKDOWN BY AGE 21 TURNOUT OVERVIEW SINCE 1979 22 TURNOUT OVERVIEW SINCE 1979 - BY MEMBER STATE 23 4. NATIONAL RESULTS BY MEMBER STATE 27-301 GOVERNMENTS AND OPPOSITION IN MEMBER STATES 28 COMPOSITION OF THE EP: 2014 AND LATEST UPDATE POLITICAL PARTIES IN THE EP MEMBERS OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT - BY MEMBER STATE EE2014 TOTAL RESULTS EE2014 ELECTORAL LISTS - BY MEMBER STATE RESULTS OF TWO LAST NATIONAL ELECTIONS AND THE EE 2014 DIRECT PRESIDENTIAL ELECTIONS SOURCES EDITORIAL First published in November 2014, the Review of European and National Elections offers a comprehensive, detailed and up-to-date overview on the composition of the European Parliament, national elections in all EU Member States as well as a historical overview on the now nearly forty years of direct elections to the European Parliament since 1979. -

Visit to Malta of Meps Ana Gomes, Sven Giegold and David Casa

Visit to Malta of MEPs Ana Gomes, Sven Giegold and David Casa (Members of the European Parliament Ad Hoc Mission on the Rule of Law in Malta, Nov/Dec 2017, following the assassination of journalist Daphne Caruana Galizia) Conclusions: 1. The investigation on the assassination of Daphne Caruana Galizia is stalling. People we spoke to suspect that the plan may be ensure the blame rests with the three suspected bombers and to eventually let them go free, after 20 months of detention. 2. Magistrate Vella, who has been in charge of the murder investigation, has been offered a promotion to become a judge and should, in a few weeks, leave the case. This is interpreted by many as a way to delay and stall the investigation. 3. The Police is ostensibly not following all relevant leads to find out who ordered the assassination. Excuses provided go from lack of resources to impossibility to investigate all people exposed by the deceased who might have had a motive to silence her. 4. Quite shockingly, the Police appeared not to have thoroughly investigated witness accounts - published by international media - that Minister of Economy, Chris Cardona (exposed by Mrs. Caruana Galizia and suing her for libel) had been seen drinking with one of the suspects prior to their arrest. 5. The Police has denied that policeman Sargent Cassar had tipped off the detainees. However, he was transferred from the investigations brigade. During the interrogation following the arrest, one Police inspector asked suspects who had tipped them off about their imminent arrest: they had no keys or phones with them, and one of the men had written his partner’s number on his arms. -

Political Advertising in the 2014 European Parliament Elections, DOI 10.1057/978-1-137-56981-3 APPENDIX 2CODEBOOKS

APPENDIX 1POLITICAL ADVERTISING PROJECT This book emerged from a content analysis study of electoral broadcasts (spots) and posters in the 2014 European Parliament elections. The project involving a coding of political advertising broadcasts and posters was led by Christina Holtz-Bacha, Edoardo Novelli and Kevin Rafter, and involved partners in different member states including: Austria: Jürgen Grimm, Christiane Grill; Belgium: Celeste Fornaro; Bulgaria: Lilia Raycheva; Cyprus: Vicky Triga, Dimitra Milioni, Kiriaki Stylianou; Croatia: Maja Simunjak, Lana Milanovic; Denmark: Orla Vigsø; Estonia: Marju Lauristin, Evelin Eikner; Finland: Tom Carlson; France: Jamil Dakhlia, Alexandre Borrell; Germany: Christina Holtz-Bacha, Greece: Stamatis Poulakidakos, Anastasia Veneti; Hungary: Norbert Merkovity, Zsusanna Mihàlyffy; Ireland: Kevin Rafter: Italy: Edoardo Novelli, Francesca Ruggieri, Melissa Mongiardo, Andrea Taddei; Latvia: Inta Brikse; Lithuania: Andrius Suminas; Luxembourg: Reimar Zeh; Malta: Carmen Sammut; Netherlands: Rens Vliegenthart, Bas Sietses; Poland: Ewa Nowak; Portugal: Iolanda Veríssimo, Claudia Alvares; Czech Republic: Anna Matuskova, Roman Hajek, Markeva Stechova; Romania: Valentina Marinescu, Silvia Branca, Bianca Mitu; Slovakia: Alena Kluknavska; Slovenia: Tomaz Dezelan, Alem Maksuti; Spain: Francisco Soane Perez; Sweden: Nicklas Håkansson, Bengt Johansson; United Kingdom: Dominic Wring, David Deacon. © The Author(s) 2017 215 C. Holtz-Bacha et al. (eds.), Political Advertising in the 2014 European Parliament Elections, -

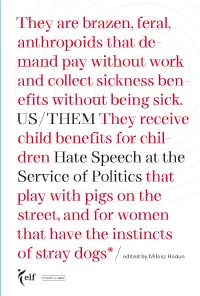

Here: on Hate Speech

They are brazen, feral, anthropoids that de- mand pay without work and collect sickness ben- efits without being sick. US / THEM They receive child benefits for chil- dren Hate Speech at the Service of Politics that play with pigs on the street, and for women that have the instincts of stray dogs * / edited by Miłosz Hodun LGBT migrants Roma Muslims Jews refugees national minorities asylum seekers ethnic minorities foreign workers black communities feminists NGOs women Africans church human rights activists journalists leftists liberals linguistic minorities politicians religious communities Travelers US / THEM European Liberal Forum Projekt: Polska US / THEM Hate Speech at the Service of Politics edited by Miłosz Hodun 132 Travelers 72 Africans migrants asylum seekers religious communities women 176 Muslims migrants 30 Map of foreign workers migrants Jews 162 Hatred refugees frontier workers LGBT 108 refugees pro-refugee activists 96 Jews Muslims migrants 140 Muslims 194 LGBT black communities Roma 238 Muslims Roma LGBT feminists 88 national minorities women 78 Russian speakers migrants 246 liberals migrants 8 Us & Them black communities 148 feminists ethnic Russians 20 Austria ethnic Latvians 30 Belgium LGBT 38 Bulgaria 156 46 Croatia LGBT leftists 54 Cyprus Jews 64 Czech Republic 72 Denmark 186 78 Estonia LGBT 88 Finland Muslims Jews 96 France 64 108 Germany migrants 118 Greece Roma 218 Muslims 126 Hungary 20 Roma 132 Ireland refugees LGBT migrants asylum seekers 126 140 Italy migrants refugees 148 Latvia human rights refugees 156 Lithuania 230 activists ethnic 204 NGOs 162 Luxembourg minorities Roma journalists LGBT 168 Malta Hungarian minority 46 176 The Netherlands Serbs 186 Poland Roma LGBT 194 Portugal 38 204 Romania Roma LGBT 218 Slovakia NGOs 230 Slovenia 238 Spain 118 246 Sweden politicians church LGBT 168 54 migrants Turkish Cypriots LGBT prounification activists Jews asylum seekers Europe Us & Them Miłosz Hodun We are now handing over to you another publication of the Euro- PhD. -

Notes in Preparation for Testimony in A) Court Case No. 395/2017: Ben Nasan Khaled Ibrahim Pen Vs. Minister of Health, Etc. B) C

Notes in Preparation for Testimony in A) Court Case No. 395/2017: Ben Nasan Khaled Ibrahim Pen vs. Minister of Health, etc. B) Court Case No. 220/2016: Gafà Neville vs. Lindsay David C) Court Case No. 221/2016: Gafà Neville vs. Lindsay David These notes contain a summary of the assertions, evidence and testimony relating to the allegations that there have been illicit sales of Schengen Visas at the Maltese Consulate in Tripoli and in the issuance of Humanitarian Medical Visas by persons in the Office of the Maltese Prime Minister. If the allegations are correct, then corrupt officials have issued up to 88,000 Schengen Visas and an unknown number of Medical Visas, permitting an inflow in to the European Union of persons that could be potential security threats and/or illegal migrants. Furthermore, there are indications that persons that should have been entitled to Medical Visas free of charge might have been forced to pay for them or, in some cases not been able to access healthcare that under government agreements were guaranteed. The scheme, if the assertions prove to be correct, has netted the persons involved millions of euros. TABLE OF CONTENT BACKGROUND.......................................................................................................................................................... 4 INTRODUCTION........................................................................................................................................................ 6 THE THREE LIBEL CASES............................................................................................................................................