Sour Grapes, Fermented Selves Musical Shulammites Modulate Subjectivity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The History of Rock, a Monthly Magazine That Reaps the Benefits of Their Extraordinary Journalism for the Reader Decades Later, One Year at a Time

L 1 A MONTHLY TRIP THROUGH MUSIC'S GOLDEN YEARS THIS ISSUE:1969 STARRING... THE ROLLING STONES "It's going to blow your mind!" CROSBY, STILLS & NASH SIMON & GARFUNKEL THE BEATLES LED ZEPPELIN FRANK ZAPPA DAVID BOWIE THE WHO BOB DYLAN eo.ft - ink L, PLUS! LEE PERRY I B H CREE CE BEEFHE RT+NINA SIMONE 1969 No H NgWOMI WI PIK IM Melody Maker S BLAST ..'.7...,=1SUPUNIAN ION JONES ;. , ter_ Bard PUN FIRS1tintFaBil FROM 111111 TY SNOW Welcome to i AWORD MUCH in use this year is "heavy". It might apply to the weight of your take on the blues, as with Fleetwood Mac or Led Zeppelin. It might mean the originality of Jethro Tull or King Crimson. It might equally apply to an individual- to Eric Clapton, for example, The Beatles are the saints of the 1960s, and George Harrison an especially "heavy person". This year, heavy people flock together. Clapton and Steve Winwood join up in Blind Faith. Steve Marriott and Pete Frampton meet in Humble Pie. Crosby, Stills and Nash admit a new member, Neil Young. Supergroups, or more informal supersessions, serve as musical summit meetings for those who are reluctant to have theirwork tied down by the now antiquated notion of the "group". Trouble of one kind or another this year awaits the leading examples of this classic formation. Our cover stars The Rolling Stones this year part company with founder member Brian Jones. The Beatles, too, are changing - how, John Lennon wonders, can the group hope to contain three contributing writers? The Beatles diversification has become problematic. -

Gknforgvillogt Folk Club Is a Non Smokingvenue

The Internationully F amous GLENFARG VILLAGE FOLK CLUB Meets everT Monday at 8.30 Pm In the Terrace Bar of The Glenfarg Hotel (01577 830241) GUEST LIST June 1999 7th SINGAROUNI) An informal, friendly and relared evening of song and banter. If you fancy performing a song, tune, poem or relating a story this is the night for you. 14th THE CORNER BOYS Drawing from a large repertoire of songs by some of the worlds finest songwriters, as well as their own fine original compositions, they sing and play with a rakish, wry humour. Lively, powerful, humorous and yet somehow strangely sensitive, their motto is... "Have Diesel will travel - book us before we die!" Rhythm Rock 'n' Folky Dokey, Goodtime Blues & Ragtime Country. 21st DAVID WILKIE & COWBOY CELTIC On the western plains of lfth Century North America, intoxicating Gaelic melodies drifted through the evening air at many a cowboy campfire. The Celtic origins of cowboy music are well documented and tonight is your chance to hear it performed live. Shake the trail dust from your jeans and mosey along for a great night of music from foot stompin' to hauntingly beautiful' 28th JULM HENIGAN As singer, instrumentalist and songwriter, Julie defies conventional categories. A native of the Missouri Ozarks, she has long had a deep affinity for American Folk Music. She plays guitar, banjo, fiddle and dulcimer. There is a strong Irish influence in Julie's music and her vocals are a stunning blend of all that is best in both the American and Irish traditions. 4th SUMMER PICNIC - LOCHORE MEADOWS, Near Kelty Z.OOpm 5th BLACKEYED BIDDY A warm welcome back to the club for this well loved pair. -

Nigel Pegrum - Studio Tel

Nigel John Pegrum – BRIEF BIO. (325 words, 1931 characters with spaces) March 2014 Bio summary 1949-1966 – Family and school days, learning music and recording including The Small Faces 1966-1973 – Various bands including Gnidrolog 1973-1989 – Steeleye Span, Plant Life Records, Pace Productions - international success as a musician and early success in production 1989-1991 – The Barron Knights – international touring 1991-present – Move to Cairns, Australia – Select Sound / Pegasus Studios – national and international awards for music production – maintaining side interest as a musician Awards – see: http://pegasusstudios.com.au/content/pegasus_studios-recording_awards.htm Websites – http://pegasusstudios.com.au & http://nigelpegrum.com.au (at the time of writing this document each site is pointing at the same content) Wiki on Nigel Pegrum - http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nigel_Pegrum Studio Tel. in Cairns, Qld., Australia - 07 4032 4700 Refer to full Bio. for more information Brief Bio. Nigel Pegrum was born in North Wales in 1949; he first started playing music aged seven, when his family moved to London. Soon after he started teaching himself about sound recording and spent much his school years creating and recording music for local clubs and playing in a range of bands, mainly as the drummer – recording in various London studios with these bands (including The Small Faces) helped him gather skills and experience along the way. From 1966 to 1973 Nigel worked with a variety of bands – in Spain and in Italy as well as in the UK – including experimental fusion band Gnidrolog, with whom he toured the UK and Europe supporting many big name bands. -

Off the Beaten Track

Off the Beaten Track To have your recording considered for review in Sing Out!, please submit two copies (one for one of our reviewers and one for in- house editorial work, song selection for the magazine and eventual inclusion in the Sing Out! Resource Center). All recordings received are included in “Publication Noted” (which follows “Off the Beaten Track”). Send two copies of your recording, and the appropriate background material, to Sing Out!, P.O. Box 5460 (for shipping: 512 E. Fourth St.), Bethlehem, PA 18015, Attention “Off The Beaten Track.” Sincere thanks to this issue’s panel of musical experts: Richard Dorsett, Tom Druckenmiller, Mark Greenberg, Victor K. Heyman, Stephanie P. Ledgin, John Lupton, Angela Page, Mike Regenstreif, Seth Rogovoy, Ken Roseman, Peter Spencer, Michael Tearson, Theodoros Toskos, Rich Warren, Matt Watroba, Rob Weir and Sule Greg Wilson. that led to a career traveling across coun- the two keyboard instruments. How I try as “The Singing Troubadour.” He per- would have loved to hear some of the more formed in a variety of settings with a rep- unusual groupings of instruments as pic- ertoire that ranged from opera to traditional tured in the notes. The sound of saxo- songs. He also began an investigation of phones, trumpets, violins and cellos must the music of various utopian societies in have been glorious! The singing is strong America. and sincere with nary a hint of sophistica- With his investigation of the music of tion, as of course it should be, as the Shak- VARIOUS the Shakers he found a sect which both ers were hardly ostentatious. -

Nigel Pegrum - Studio Tel

Nigel John Pegrum – BRIEF BIO. (750 words, 4397 characters with spaces) February 2014 Bio summary 1949-1966 – Family and school days, learning music and recording including The Small Faces 1966-1973 – Various bands including Gnidrolog 1973-1989 – Steeleye Span, Plant Life Records, Pace Productions - international success as a musician and early success in production 1989-1991 – The Barron Knights – international touring 1991-present – Move to Cairns, Australia – Select Sound / Pegasus Studios – national and international awards for music production – maintaining side interest as a musician Awards – see: http://pegasusstudios.com.au/content/pegasus_studios-recording_awards.htm Websites – http://pegasusstudios.com.au & http://nigelpegrum.com.au (at the time of writing this document each site is pointing at the same content) Wiki on Nigel Pegrum - http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nigel_Pegrum Studio Tel. in Cairns, Qld., Australia - 07 4032 4700 Bio. Nigel Pegrum was born in North Wales then moved to London with his parents when he was seven. It was there he began taking piano lessons, and taught himself guitar and ukulele for fun! At the age of nine he started experimenting with analogue tape recorders, creating and recording music for school plays and local film club movies. At eleven years old Nigel joined the school ‘rock band’ on drums and recorded a few demo tapes using homemade equipment. From age eleven to seventeen he played with a range of bands, including fledgling London band The Small Faces who of course went on to great things. During this time he recorded in many London studios – now legends in their own right – gathering skills and experience along the way. -

Representation Through Music in a Non-Parliamentary Nation

MEDIANZ ! VOL 15, NO 1 ! 2015 DOI: 10.11157/medianz-vol15iss1id8 - ARTICLE - Re-Establishing Britishness / Englishness: Representation Through Music in a non-Parliamentary Nation Robert Burns Abstract The absence of a contemporary English identity distinct from right wing political elements has reinforced negative and apathetic perceptions of English folk culture and tradition among populist media. Negative perceptions such as these have to some extent been countered by the emergence of a post–progressive rock–orientated English folk–protest style that has enabled new folk music fusions to establish themselves in a populist performance medium that attracts a new folk audience. In this way, English politicised folk music has facilitated an English cultural identity that is distinct from negative social and political connotations. A significant contemporary national identity for British folk music in general therefore can be found in contemporary English folk as it is presented in a homogenous mix of popular and world music styles, despite a struggle both for and against European identity as the United Kingdom debates ‘Brexit’, the current term for its possible departure from the EU. My mother was half English and I'm half English too I'm a great big bundle of culture tied up in the red, white and blue (Billy Bragg and the Blokes 2002). When the singer and songwriter, Billy Bragg wrote the above song, England, Half English, a friend asked him whether he was being ironic. He replied ‘Do you know what, I’m not’, a statement which shocked his friends. Bragg is a social commentator, political activist and staunch socialist who is proudly English and an outspoken anti–racist, which his opponents may see as arguably diametrically opposed combination. -

Dypdykk I Musikkhistorien - Del 27: Folkrock (25.11.2019 - TFB) Oppdatert 03.03.2020

Dypdykk i musikkhistorien - Del 27: Folkrock (25.11.2019 - TFB) Oppdatert 03.03.2020 Spilleliste pluss noen ekstra lyttetips: [Bakgrunnsmusikk: Resor och näsor (Under solen lyser solen (2001) / Grovjobb)] Starten Beatles og British invasion The house of the rising sun (The house of the rising sun (1964, singel) / Animals) Mr. Tambourine Man (Mr. Tambourine Man (1965) / Byrds) Candy man ; The Devil's got my woman (Candy man (1966, singel) / Rising Sons) Maggies farm Bob Dylan Live at the Newport Folk Festival USA One-way ticket ; The falcon ; Reno Nevada Celebrations For A Grey Day (1965) / Mimi & Richard Fariña From a Buick 6 (Highway 61 revisited (1965) / Bob Dylan) Sounds of silence (Sounds of silence (1966) / Simon & Garfunkel) Hard lovin’ looser (In my life (1966) / Judy Collins) Like a rolling stone (Live 1966 (1998) / Bob Dylan) 1 Eight miles high (Fifth Dimension (1966) / The Byrds) It’s not time now ; There she is (Daydream (1966) / The Lovin’ Spoonful) Jefferson Airplane takes off (1966) / Jefferson Airplane Carnival song ; Pleasant Street Goodbye And Hello (1967) / Tim Buckley Pleasures Of The Harbor (1967) I Phil Ochs Virgin Fugs (1967) / The Fugs Alone again or (Forever changes (1967) / Love) Morning song (One nation underground (1967) / Pearls Before Swine) Images of april (Balaklava (1968) / Pearls Before Swine) Rainy day ; Paint a lady (Paint a lady (1970) / Susan Christie) Country rock Buffalo Springfield Taxim (A beacon from Mars (1968) / Kaleidoscope) Little hands (Oar (1969) / Skip Spence) Carry on Deja vu (1970) / Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young 2 Britisk Donovan Sunshine superman (1966) The river song ; Jennifer Juniper The Hurdy Gurdy Man (1968) You know what you could be (The 5000 spirits or the layers of the onion (1967) / The Incredible String Band) Astral weeks (1968) / Van Morrison Child star (My People Were Fair And Had Sky In Their Hair.. -

Eleanor Mcevoy One of Ireland’S Most Accomplished Contemporary Female Singer/Songwriters

Dates For Your Diary Folk Federation of New South Wales Inc Folk News Issue 480 October - November 2016 $3.00 Dance News CD Reviews Eleanor McEvoy one of Ireland’s most accomplished contemporary female singer/songwriters folk music dance festivals reviews profiles diary dates sessions opportunities ADVERTISING SIZES Size mm Members Not Mem October-November 2016 Full page 210 x 297 $80 $120 In this issue Folk Federation of New South Wales Inc 1/2 page 210 x 146 $40 $70 Presidents Report p3 Post Office Box A182 or Dates for your diary p4 102 x 146 Sydney South NSW 1235 Festival News p9 ISSN 0818 7339 ABN9411575922 1/4 page 102 x 146 $25 $50 Folk News p10 jam.org.au 1/8 page 102 x 70 $15 $35 The Anti-Conscription Centenary p10 The Folk Federation of NSW Inc, Advertising artwork required by 5th Dance News p11 formed in 1970, is a Statewide body of each month. Advertisements can Vale: Jim Macquarrie p11 which aims to present, support, encour- be produced by Cornstalk if required. Steeleye Span Guitarist in Aust. p11 age and collect folk music, folk dance, Please contact the editor for enquiries Ewan MacColl, A Retrospective p12 folklore and folk activities as they about advertising (02) 6493 6758 exist in Australia in all their forms. It Folk Contacts p17 provides a link for people interested All cheques for advertisements and December 2016-January 2017 in the folk arts through its affiliations inserts to be made payable to the Folk with folk clubs throughout NSW and its Federation of NSW Inc Deadline date: 12th Dec 2016. -

14302 76969 1 1>

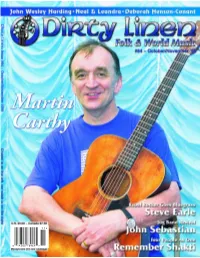

11> 0514302 76969 establishment,” he hastened to clarify. “I wish it were called the Legion of Honour, but it’s not.” Still in all, he thinks it’s good for govern- M artin C arthy ments to give cultural awards and is suitably honored by this one, which has previously gone to such outstanding folk performers as Jeannie Robertson. To decline under such circum- stances, he said, would have been “snotty.” Don’t More importantly, he conceives of his MBE as recognition he shares with the whole Call Me folk scene. “I’ve been put at the front of a very, very long queue of people who work hard to make a folk revival and a folk scene,” he said. Sir! “All those people who organized clubs for nothing and paid you out of their own pocket, and fed you and put you on the train the next morning, and put you to bed when you were drunk! What [the government is] doing, is taking notice of the fact that something’s going on for the last more than 40 years. It’s called the folk revival. They’ve ignored it for that long. And someone has suddenly taken notice, and that’s okay. A bit of profile isn’t gonna hurt us — and I say us, the plural, for the folk scene — isn’t gonna hurt us at all.” In the same year as Carthy’s moment of recognition, something happened that did hurt the folk scene. Lal Waterson, Carthy’s sister-in- law, bandmate, near neighbor and close friend, died of cancer. -

Dave and Maggie Hunt

Citation for Dave and Maggie Hunt It is unlikely that the people assembled here in Abbots Bromley will not know of Dave and Maggie Hunt and have some appreciation of their status not only in the folk world but also on its fringes. This Gold Badge Award gives us the opportunity to look back on two varied careers that have, separately and together, brought richness to folk music and community arts over many years. It also provides the opportunity to learn things about the two of them that perhaps were not apparent because you’ve only came across them in one of their guises. In the words of a non-folk song, ‘Let’s start at the very beginning – a very good place to start!’ Like many of us, Dave came to folk music in the 50s via Skiffle, and given its relationship to American folk music there was a natural progression to English folk music and that of its neighbours. The CND marches of his youth also provided a basic repertoire, but early exposure, via work at the Edinburgh Festival, to the likes of Rae and Archie Fisher, Bobby Campbell and Gordie McCulloch, Hamish Imlach, Norman Kennedy, and more started to broaden his knowledge. As an early attendee in 1963 of Wolverhampton’s Giffard Folk Club (he went to its second meeting for the princely entrance donation of 6d – six old pence) he soon graduated to resident status and then on to the committee of a club that was the starting point for all manner of folk activity, as we will see. -

Topic Records 80Th Anniversary Start Time: 8Pm Running Time: 2 Hours 40 Minutes with Interval

Topic Records 80th Anniversary Start time: 8pm Running time: 2 hours 40 minutes with interval Please note all timings are approximate and subject to change Martin Aston discusses the history behind the world’s oldest independent label ahead of this collaborative performance. When Topic Records made its debut in 1939 with Paddy Ryan’s ‘The Man That Waters The Workers’ Beer’, an accordion-backed diatribe against capitalist businessmen who underpay their employees, it’s unlikely that anyone involved was thinking of the future – certainly not to 2019, when the label celebrates its 80th birthday. In any case, the future would have seemed very precarious in 1939, given the outbreak of World War II, during which Topic ceased most activity (shellac was particularly hard to source). But post-1945, the label made good on its original brief: ‘To use popular music to educate and inform and improve the lot of the working man,’ explains David Suff, the current spearhead of the world’s oldest independent label – and the undisputed home of British folk music. Tonight at the Barbican (where Topic held their 60th birthday concerts), musical director Eliza Carthy – part of the Topic recording family since 1997, though her parents Norma Waterson and Martin Carthy have been members since the sixties and seventies respectively - has marshalled a line-up to reflect the passing decades, which hasn’t been without its problems. ‘We have far too much material, given it’s meant to be a two-hour show!’ she says. ‘It’s impossible to represent 80 years – you’re talking about the left-wing leg, the archival leg, the many different facets of society - not just communists but farmers and factory workers - and the folk scene in the Fifties, the Sixties, the Seventies.. -

Summer 2013 and Music Club Snape and Potiphar’S Apprentices

NNootteess The Newsletter of Readifolk Issue 18 Reading's folk song Summer 2013 and music club Snape and Potiphar’s Apprentices. You can read all about these me two acts, as well as all the other artists who are appearing at Welco the club during the coming quarter, in the preview section on pages 4 and 5. to another Readifolk Do make a special note of our Grand Charity Concert on 14 newsletter July which features our very own band Rye Wolf. Rye Wolf play a mix of traditional and selfpenned songs in true folk style and Rumblings from the Roots are rapidly making a name for themselves in the local area and further afield. The concert is in support of the local community Welcome to the Summer edition of Notes. radio station, Reading4U, which is of course where many of the band performers and others from Readifolk broadcast the Once again our editor has managed to put together a weekly Readifolk Radio Show (Friday evenings 6 8 pm on newsletter packed with interesting articles and information www.reading4u.co.uk). Reading Community Radio is run which we hope you will enjoy reading. We thank all of the entirely by volunteers there are no paid employees, and it contributors to this issue of Notes for their considerable efforts. relies on donations, sponsorship etc. for its funding. We hope that with your help this concert will be able to make a sizeable As usual you will find on the back page the full programme of contribution to those funds. events at Readifolk during the next three months.