Knowledge Management Implementation in a Library: Mapping Tools and Technologies to Phases of the KM Cycle

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Uila Supported Apps

Uila Supported Applications and Protocols updated Oct 2020 Application/Protocol Name Full Description 01net.com 01net website, a French high-tech news site. 050 plus is a Japanese embedded smartphone application dedicated to 050 plus audio-conferencing. 0zz0.com 0zz0 is an online solution to store, send and share files 10050.net China Railcom group web portal. This protocol plug-in classifies the http traffic to the host 10086.cn. It also 10086.cn classifies the ssl traffic to the Common Name 10086.cn. 104.com Web site dedicated to job research. 1111.com.tw Website dedicated to job research in Taiwan. 114la.com Chinese web portal operated by YLMF Computer Technology Co. Chinese cloud storing system of the 115 website. It is operated by YLMF 115.com Computer Technology Co. 118114.cn Chinese booking and reservation portal. 11st.co.kr Korean shopping website 11st. It is operated by SK Planet Co. 1337x.org Bittorrent tracker search engine 139mail 139mail is a chinese webmail powered by China Mobile. 15min.lt Lithuanian news portal Chinese web portal 163. It is operated by NetEase, a company which 163.com pioneered the development of Internet in China. 17173.com Website distributing Chinese games. 17u.com Chinese online travel booking website. 20 minutes is a free, daily newspaper available in France, Spain and 20minutes Switzerland. This plugin classifies websites. 24h.com.vn Vietnamese news portal 24ora.com Aruban news portal 24sata.hr Croatian news portal 24SevenOffice 24SevenOffice is a web-based Enterprise resource planning (ERP) systems. 24ur.com Slovenian news portal 2ch.net Japanese adult videos web site 2Shared 2shared is an online space for sharing and storage. -

Slides for Students

SLIDES FOR STUDENTS The Effective Use of Powerpoint in Education GARY D. FISK SLIDES FOR STUDENTS The Effective Use of Powerpoint in Education GARY D. FISK Blue Ridge | Cumming | Dahlonega | Gainesville | Oconee Copyright © 2019 by Gary D. Fisk All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in whole or in part without written permission from the publisher, except by reviewers who may quote brief excerpts in connections with a review in newspaper, magazine, or electronic publications; nor may any part of this book be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or other, without the written permission from the publisher. Published by: University of North Georgia Press Dahlonega, Georgia Printing Support by: Lightning Source Inc. La Vergne, Tennessee Book design by Corey Parson. ISBN: 978-1-940771-43-4 Printed in the United States of America For more information, please visit: http://ung.edu/university-press Or e-mail: [email protected] CONTENTS 0 Introduction vii 1 Presentation Software 1 2 Powerpointlessness 14 3 Educational Effectiveness and Student Perceptions 32 4 Avoiding Death by Powerpoint 53 5 Design for Emotion I 67 6 Design for Emotion II 84 7 Design for Sensation 100 8 Design for Perception I 117 9 Design for Perception II 135 10 Design for Attention 156 11 Design for Cognition I 170 12 Design for Cognition II 190 13 Design for Behavior 213 14 Technology Choices 232 15 Tips and Tricks for Slide Presentations 247 16 A Classroom Presentation Example 264 17 The Bright Future of Powerpoint in Education 292 A Appendix A 307 B Appendix B 310 C Appendix C 314 0 INTRODUCTION The creative spark that motivated this book was the observation that powerpoint presentations sometimes fail to produce a positive impact on student learning. -

Pretzi Free Download Free Powerpoint Presentation Templates for Students

pretzi free download Free Powerpoint Presentation Templates For Students. Transcript: Pros Not very different from powerpoint Limited options for creativity Can’t import videos Complicated Motion Sickness Time Consuming Fun for Students Free! Templates Alternatives to PowerPoint Complicated at first Can’t work offline with free version Still uses slides like powerpoint Not free! Works with flash Must download software Cons Cons Not very different from powerpoint Must download OpenOffice software Limited options for creativity Pros Cons Easy transition from powerpoint Free! New and improved Free! Social networking options Different, but easier than prezi http://www.prezi.com SlideRocket Pros http://www.sliderocket.com By: Kirsten Johnson Cons Flair Pros Prezi Google Presentations Easy transition from powerpoint Free! More options than google presentation Pros Pros Impress Its an app! Converts powerpoint files to flash Built in audio and video capabilities Cons Cons. Templates Presentation. Transcript: 1- The user creates a New Space 2- During some time it's modified according to the project needs 3- As the space results useful for a whole company or area the user decides to ask for saving it as Template 4-The Collaborate Team takes care of this process 5- The new process covers the Analysis of the Space that we should save as Template and the Estimation to finish it. 6- Also we should contemplate the current release dates to provide the user the go live Date Save Templates with Content Some Issues are: New Process: 1- URLs that are inherited -

200 Free Tools

200+ Free Book Marketing and Author Tools Book Marketing on a Shoestring Budget: 200+ Free Book Marketing and Author Tools Expand Your Book Marketing Efforts Without Going Broke! With Shelley Hitz, www.Self-Publishing-Coach.com © Self-Publishing-Coach.com - All Rights Reserved. www.self-publishing-coach.com Page 2 200+ Free Book Marketing and Author Tools NOTICE: You DO Have the Right to Reprint or Resell this Report! You Also MAY Give Away, Sell or Share the Content Herein © 2011 Copyright www.Self-Publishing-Coach.com. All rights reserved. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. You may sell or give away this report as long as it is not altered in any way, falsely misrepresented or distributed in any illegal or immoral manner. © Self-Publishing-Coach.com - All Rights Reserved. www.self-publishing-coach.com Page 3 200+ Free Book Marketing and Author Tools About The Expert Shelley Hitz Shelley Hitz is an entrepreneur, speaker, author and consultant to individuals, organizations and small businesses who want to multiply their impact through self publishing. She teaches from personal experience. Over a two year span, while working full-time, she self published five books, multiple audio CDs, authored two websites that attract thousands of visitors each month, and created multiple products that she sells through her website and at her speaking engagements. Her website, www.Self-Publishing-Coach.com also offers free book templates, articles, monthly newsletter, tele-classes, special reports, e-books, webinars, podcasts, videos and other resources to help you get self published! www.facebook.com/selfpublishingcoach www.twitter.com/self_publish www.youtube.com/selfpublishingcoach © Self-Publishing-Coach.com - All Rights Reserved. -

Smart Content Providers

Smart Content Providers Video Audio Photos Products/Other #REKT Acast 23hq 23degrees ABC News Adori Labs Accredible 360 Panorama Adventr Allears Achewood 360 Stories Adways Anchor FM Altizure 3DCrafts Alkışlarla Yaşıyorum ART19 deviantART Abstract All Things Digital AudioBoom Dinosaur Comics Acebot.ai Altru Audiomack Dribbble Airtable Alugha Audm Droplr Allego Aniboom Ausha EyeEm Allihoopa Animoto Backtracks Flickr Alpaca Maps Athenascope Bandcamp gfycat Alpha Hat Bambuser BingeWith GifVif Apester Brightcove BlogAudio Giphy AppFollow Buto.tv Blogcast Img.ly Apple Keynote CANAL+ Bubbli Imgur ArcGIS StoryMaps Cayke Buzzsprout instagram Archilogic CBS News Cadence 13 Kuula ARCHIVOS Cinema8 Canva meadd Are.na Cinnamon Changelog Mobypicture AskMen Cincopa Chirbit Momento360 Autodesk Screencast Clip Syndicate Clyp Ow.ly Avocode Clipfish DNBRadio PanoMoments Bad Panda Clippit Flat Pexels Badgr CloudApp Free Music Archive photozou BadJupiter CNBC Genius pikchur Beautiful AI CNN Grooveshark Pollstar Behance CNN Edition Himalaya Publitio Bitmark CNN Money Huffduffer Questionable Content Blogsend.io College Humor iHeartRadio Represent BlueprintUE Confreaks Infinity.fm SmugMug Bootkik Coub Instaread Someecards Boston.com Crackle Last.fm The Hype Machine Box Office Buz Daily Motion Liberated Syndication Tinypic Brainshark Discovery Channel Listle tochka.net Brainsonic dotSUB Listen Notes TwitrPix BranchTrack Dream Broker Megafono uludağ sözlük galeri Bravo Tv DTube Megaphone.fm Vidme buk.io Embedded Mymixtapez Minilogs xkcd Buncee embedly Mixcloud Zoomable -

Conceptual and Technical Foundations for Next Generation Presentation Solutions

Vrije Universiteit Brussel Faculty of Sciences and Bioengineering Sciences Department of Computer Science MindXpres Conceptual and Technical Foundations for Next Generation Presentation Solutions PhD Candidate: Promoter: Reinout Roels Prof. Dr. Beat Signer Dissertation submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Sciences Members of the Jury Prof. Dr. Olga De Troyer Vrije Universiteit Brussel (Chair) Prof. Dr. Johan Loeckx Vrije Universiteit Brussel (Secretary) Prof. Dr. Beat Signer Vrije Universiteit Brussel (Promoter) Prof. Dr. Jo Tondeur Vrije Universiteit Brussel Prof. Dr. Kris Luyten Universiteit Hasselt Prof. Dr. Katrien Verbert KU Leuven May 2019 Abstract Presentation software such as PowerPoint, also known as slideware, has become a de facto standard as support for oral presentations. However, these tools were initially created as simulators for physical slides and have adopted many of their characteris- tics, including their limitations. These limitations include a strictly linear navigation of presentations, relatively static content and a tedious and time-consuming author- ing process. Presentation software was introduced over 30 years ago but these tools have changed very little since their inception. This is especially remarkable given the other technological advances that were made in the same timespan. Even though slideware may not be the optimal medium for all scenarios, the fact remains that it is used everywhere. Therefore, addressing existing shortcomings and unmet user needs can have a major impact. In this dissertation we start by investigating the existing shortcomings of presentation tools. By means of a literature study, observations, a survey and the programmatic analysis of more than 12 000 PowerPoint documents, we derive user needs and pinpoint issues that should be addressed. -

OSINT Handbook September 2020

OPEN SOURCE INTELLIGENCE TOOLS AND RESOURCES HANDBOOK 2020 OPEN SOURCE INTELLIGENCE TOOLS AND RESOURCES HANDBOOK 2020 Aleksandra Bielska Noa Rebecca Kurz, Yves Baumgartner, Vytenis Benetis 2 Foreword I am delighted to share with you the 2020 edition of the OSINT Tools and Resources Handbook. Once again, the Handbook has been revised and updated to reflect the evolution of this discipline, and the many strategic, operational and technical challenges OSINT practitioners have to grapple with. Given the speed of change on the web, some might question the wisdom of pulling together such a resource. What’s wrong with the Top 10 tools, or the Top 100? There are only so many resources one can bookmark after all. Such arguments are not without merit. My fear, however, is that they are also shortsighted. I offer four reasons why. To begin, a shortlist betrays the widening spectrum of OSINT practice. Whereas OSINT was once the preserve of analysts working in national security, it now embraces a growing class of professionals in fields as diverse as journalism, cybersecurity, investment research, crisis management and human rights. A limited toolkit can never satisfy all of these constituencies. Second, a good OSINT practitioner is someone who is comfortable working with different tools, sources and collection strategies. The temptation toward narrow specialisation in OSINT is one that has to be resisted. Why? Because no research task is ever as tidy as the customer’s requirements are likely to suggest. Third, is the inevitable realisation that good tool awareness is equivalent to good source awareness. Indeed, the right tool can determine whether you harvest the right information. -

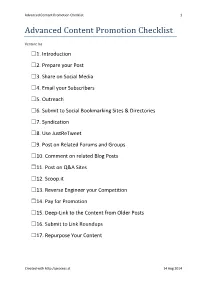

Advanced Content Promotion Checklist 1

Advanced Content Promotion Checklist 1 Advanced Content Promotion Checklist Venture Inc ☐ 1. Introduction ☐ 2. Prepare your Post ☐ 3. Share on Social Media ☐ 4. Email your Subscribers ☐ 5. Outreach ☐ 6. Submit to Social Bookmarking Sites & Directories ☐ 7. Syndication ☐ 8. Use JustReTweet ☐ 9. Post on Related Forums and Groups ☐ 10. Comment on related Blog Posts ☐ 11. Post on Q&A Sites ☐ 12. Scoop.it ☐ 13. Reverse Engineer your Competition ☐ 14. Pay for Promotion ☐ 15. Deep-Link to the Content from Older Posts ☐ 16. Submit to Link Roundups ☐ 17. Repurpose Your Content Created with http://process.st 14 Aug 2014 Advanced Content Promotion Checklist 2 ☐ 1. Introduction Content marketing is not easy, it takes a lot of elbow grease to create valuable content and even more to promote it! The promotion part is something that many companies tend to miss when looking at a content marketing strategy. A general rule of thumb is you should spend 30% of your time creating content and 70% promoting it. That’s why I created this checklist you can use to promote the content you work so hard to create. I’m writing this checklist for two purposes. Firstly, because I am interested in content promotion for my own company Process Street. Content marketing is something I’ve been experimenting with and seeing some great results with so far, writing this post is forcing me to research and learn more about content distribution. Secondly, because I want to make a template for this in Process Street so I can begin hand it off to my team. I am working towards a streamlined content marketing machine. -

Web 2.0 and Social Media for Business

Web 2.0 and Social Media for Business Roger McHaney Download free books at Roger W. McHaney Web 2.0 and Social Media for Business Download free eBooks at bookboon.com 2 Web 2.0 and Social Media for Business 2nd edition © 2013 Roger W. McHaney & bookboon.com ISBN 978-87-403-0514-2 Download free eBooks at bookboon.com 3 Web 2.0 and Social Media for Business Contents Contents 1 Introduction to Web 2.0 8 1.1 The Internet and World Wide Web 8 1.2 Web 2.0 Defined 10 1.3 Conclusions 31 1.4 Bibliography 31 2 Blogging for Business 34 2.1 Voice and Personality 36 2.2 Blog Environments 42 2.3 Building a Blog 48 2.4 Conclusions 68 2.5 Bibliography 68 3 More Blogging: WordPress Options 70 3.1 Customizing a WordPress Blog 70 3.2 General Settings 81 - ste the of th + - c + in ++ ity Be a part of the equation. RMB Graduate Programme applications are now open. Visit www.rmb.co.za to submit your CV before the 23rd of August 2013. Download free eBooks at bookboon.com 4 Click on the ad to read more Web 2.0 and Social Media for Business Contents 3.3 Using Widgets 83 3.4 Blog Posts 86 3.5 Adding Mobile and iPad Options 90 3.6 Managing Pages 92 3.7 Connecting with Search Engines 94 3.8 Connecting with Customers 98 3.9 Conclusions 103 3.10 Bibliography 103 4 Beyond Blogging: RSS and Podcasting 104 4.1 RSS Defined 104 4.2 RSS in Practice 109 4.3 Podcasting 118 4.4 Conclusions 134 4.5 Bibliography 135 5 Videocasting, Screencasting and Live Streaming 136 5.1 Videocasting 136 5.2 Screencasting 153 5.3 Live Streaming 156 The next step for top-performing graduates Masters in Management Designed for high-achieving graduates across all disciplines, London Business School’s Masters in Management provides specific and tangible foundations for a successful career in business. -

A Visually Impaired Law Clerk and the Supreme Court Linda C

Accommodations: What Libraries Do to Serve Patrons with Disabilities Working with Isaac: A Visually Impaired Law Clerk and the Supreme Court Linda C. Corbelli, Research Librarian and Melissa A. Williams, Technology/Research Librarian, Supreme Court of the United States Library I. Introduction arrival, the law clerks receive training from the During the October 2008 Term, retired Justice Office of Data Systems as well as the Library. Sandra Day O’Connor employed the Supreme These training sessions are designed to intro- DCourt’s first blind law clerk, Isaac Lidsky1. Dur- duce the law clerks to the resources available ing his time at the Court, Isaac worked on cir- to them during their tenure at the Court. The cuit court cases assigned to Justice O’Connor, Library utilizes PowerPoint slides, video, discus- as well as cases before the Supreme Court with sion and handouts to introduce various Library Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s chamber. His services and their access points. At the conclu- unique needs presented the Library’s staff with sion of the presentation the clerks are taken on both opportunities and challenges. Our tra- a Library tour. ditional methods of providing services often A basic explanation is in order to understand did not work well, and sometimes not at all, how the Library staff generally serves sighted for Isaac. Several existing procedures had to be law clerks. There are four Library departments adapted and new processes had to be developed continued on page 3 in order to deliver information to him in a use- ful format. Because of the nature and volume of the law clerks’ work, prompt implementa- tion was critical. -

An Investigation Into the Impact of Visual Aids in Post-Compulsory Education (Are Text-Based Slides the Optimum?)

An investigation into the impact of visual aids in post-compulsory education (Are text-based slides the optimum?) Submitted by Nick Louis Napper to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Education in April 2014 This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. Signature: ………………………………………………………….. 1 2 Abstract This study seeks insight into the use of visual aids in contemporary post-compulsory teaching. The importance of the study is linked to the large number of students who enter Higher Education; many of whom regularly receive lectures supported by visual displays which comprise textual summaries of a lecturer’s speech. This thesis comprises a two-part study and employs a mixed methods approach. The first part inquires into teachers’ and lecturers’ practice with regard to their visual aids, and the second compares the effectiveness of text, images and imagery displayed in support of a lecture. The investigation into lecturers’ practice found many post-compulsory teachers and lecturers had received no training in the design and use of visual aids during their initial teacher training. It is suggested this privation may underpin a de facto choice of projected text as a visual aid, the use of which is not clearly supported by contemporary models of memory and mental processing. -

Content Migration and Layout for the Mindxpres Presentation Tool

Faculteit Wetenschappen Departement Informatica en Toegepaste Informatica Content Migration and Layout for the MindXpres Presentation Tool Proefschrift ingediend met het oog op het behalen van de graad van Master in de Toegepaste Informatica Joris Vandermeersch Promotor: Prof. Dr. Beat Signer Begeleider: Reinout Roels Augustus 2015 Faculty of Science Department of Computer Science and Applied Computer Science Content Migration and Layout for the MindXpres Presentation Tool Graduation thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master in Applied Computer Science Joris Vandermeersch Promoter: Prof. Dr. Beat Signer Advisor: Reinout Roels August 2015 SAMENVATTING Klassieke presentaties worden wereldwijd gebruikt om kennis over te bren- gen en te delen. Microsoft PowerPoint is het populairste en meest bekende programma in dit gebied. Spijtig genoeg heeft deze software weinig evolu- tie gekend sinds ze het licht zag in de jaren 1980, ondanks een ongeloof- lijke stortvloed aan vernieuwingen in bijna elk ander aspect van informatie- en communicatietechnologie. Het basisconcept van digitale presentaties is steeds hetzelfde gebleven, gebaseerd op de oorspronkelijke fysieke overhead- en diaprojecties. De beperkingen in grootte zorgen vaak voor een minder dan ideale weergave van informatie, waardoor het moeilijk wordt voor de presentator om alles goed te kunnen uitleggen, alsook voor het publiek om alles te begrijpen. Presentatoren ondervinden vaak, tot zelfs gewoonlijk, problemen met het schikken van hun inhoud binnen dit formaat op een manier die duidelijk, overzichtelijk en esthetisch verantwoord is. Het grootste deel van de tijd nodig om een presentatie te maken wordt verspild aan het zoeken van een goede layout voor de voorziene informatie, vaak dan nog met weinig positief resultaat.