Wilhelm Spiegelberg a Life in Egyptology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cyberscribe 169-Sept 2009

Cyberscribe 169 1 CyberScribe 169 - September 2009 The CyberScribe did a little math this month and discovered that this issue marks the beginning of his fifteenth year as the writer of this column. He has no idea how many news items have been presented and discussed, but together we have covered a great deal of the Egyptology news during that time. Hopefully you have enjoyed the journey half as much as did the CyberScribe himself. And speaking of longevity, Zahi Hawass confirmed that he is about to retire from his position as head of the Supreme Council of Antiquities. Rumors have been rife for years as to how long he’d remain in this very important post. He has had a much longer tenure than most who held this important position, but at last his task seems to be ending. His times have been marked by controversy, confrontations, grandstanding and posturing…but at the same time he has made very substantial changes in Egyptology, in the monuments and museums of Egypt and in the preservation of Egypt’s heritage. Zahi Hawass has been the consummate showman, drawing immense good will and news attention to Egypt. Here is what he, himself, said about this retirement (read the entire article here, http://tiny.cc/4Q4wq), and understand that the quote below is just part of the interview: “Interviewer: Dr. Hawass, is it true that you plan to retire from the SCA next year? “Zahi Hawass: Yes, by law I have to retire. “Interviewer: What are your plans after leaving office? “Zahi Hawass: I will continue my excavations in the Valley of the Kings, writing books, give lectures everywhere.” This is surprising news, for the retirement of Hawass and the appointment of a successor has been a somewhat taboo subject among Egyptologists. -

Howard Carter

Howard Carter Howard Carter was a British archaeologist and Egyptologist who became famous when he uncovered an intact Egyptian tomb more than 3,000 years after it had been sealed. Early Life Howard was born on 9th May 1874 in Kensington, London. Howard’s father was an artist and taught him how to draw and paint the world around him accurately. These skills would prove to be essential in Howard’s later years. As a young child, Howard spent a lot of time with his relatives in Norfolk. It was here that his interest in Egyptology began, inspired by the nearby Didlington Hall. This manor house was home to a large collection of ancient Egyptian artefacts and it is believed that this is where Howard first decided that he wanted to become an archaeologist. When he was 17, Howard started work as an archaeological artist, creating drawings and diagrams of important Egyptian finds. Excavating in the Valley of the Kings After becoming an archaeologist and working on several dig sites, Howard Carter was approached by a wealthy man named Lord Carnarvon. Lord Carnarvon had a particular interest in an Egyptian location called the Valley of the Kings – the burial place of many Egyptian pharaohs. After hearing rumours of hidden treasures in the valley, Lord Carnarvon offered to fund an excavation which was to be led by Howard Carter. After working in harsh conditions for several years, Howard and his team had found very little. Frustrated with the lack of discovery, Lord Carnarvon told Howard that if nothing was found within the year, he would stop funding the excavation. -

German Centre for Cardiovascular Research (DZHK) ANNUAL REPORT

German Centre for Cardiovascular Research (DZHK) ANNUAL REPORT 2015 The DZHK is the largest research institution for cardiovascular diseases in Germany. Our goal is to promote scientific innovation and to bring it quickly into clinical application and to patient care in order to improve the prevention, diagnosis and treatment of cardiovascular diseases. Contents 3 Preface 4 1. The German Centre for Cardiovascular Research 5 2. Highlights in 2015 8 3. Research Strategy – Focus on Translation 10 4. Preclinical Research 13 5. Clinical Research 18 6. Research Highlights at the DZHK 28 7. Scientific Infrastructures and Resources at the DZHK 35 8. Cooperation and Scientific Exchange at the DZHK 40 9. External Cooperations 43 10. Promotion of Junior Scientists – the Young DZHK 46 11. The DZHK in the Public 52 12. Indicators of the Success of Translational Research at the DZHK 54 Facts and figures The German Centres for Health Research 57 Number of partners in the registered association 58 Finances and Staff 60 Scientific Achievements 67 Personalia, Prizes and Awards 69 Committees and Governance of the DZHK 71 Sites 75 Acronyms 82 Imprint 83 The German Centre for Cardiovascular Research | ANNUAL REPORT 2015 4 Preface In 2015, the DZHK once again recorded an excep- and promise to provide new knowledge and treatment tional growth. About 1,200 people now belong to our recommendations for important endemic diseases, such network: physicians, pharmacologists, physiologists, as heart failure and myocardial infarction. The coop- biologists, chemists, physicists, biostatisticians, ethicists erations between sites, between disciplines and even and many others. We incorporated the Cardiological within institutions have been intensified. -

Obituary Notices

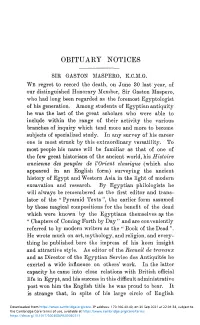

OBITUARY NOTICES SIR GASTON MASPEEO, K.C.M.G. WE regret to record the death, on June 30 last year, of our distinguished Honorary Member, Sir Gaston Maspero, who had long been regarded as the foremost Egyptologist of his generation. Among students of Egyptian antiquity he was the last of the great scholars who were able to include within the range of their activity the various branches of inquiry which tend more and more to become subjects of specialized study. In any survey of his career one is most struck by this extraordinary versatility. To most people his name will be familiar as that of one of the few great historians of the ancient world, his Histoire ancienne des peuples de I'Orient classique (which also appeared m an English form) surveying the ancient history of Egypt and Western Asia in the light of modern excavation and research. By Egyptian philologists he will always be remembered as the first editor and tems- lator of the " Pyramid Texts ", the earlier form assumed by those magical compositions for the benefit of the dead which were known by the Egyptians themselves as the " Chapters of Coming Forth by Day " and are conveniently referred to by modern writers as the " Book of the Dead ". He wrote much on art, mythology, and religion, and every- thing he published bore the impress of his keen insight and attractive style. As editor of the Recueil de travaux and as Director of the Egyptian Service des Antiquites he exerted a wide influence on others' work. In the latter capacity he came into close relations with British official life in Egypt, and his success in this difficult administrative post won him the English title he was proud to bear. -

Egyptian Religion a Handbook

A HANDBOOK OF EGYPTIAN RELIGION A HANDBOOK OF EGYPTIAN RELIGION BY ADOLF ERMAN WITH 130 ILLUSTRATIONS Published in tile original German edition as r handbook, by the Ge:r*rm/?'~?~~ltunf of the Berlin Imperial Morcums TRANSLATED BY A. S. GRIFFITH LONDON ARCHIBALD CONSTABLE & CO. LTD. '907 Itic~mnoCLAY B 80~8,L~~II'ED BRIIO 6Tllll&I "ILL, E.C., AY" DUN,I*Y, RUFIOLP. ; ,, . ,ill . I., . 1 / / ., l I. - ' PREFACE TO THE ENGLISH EDITION THEvolume here translated appeared originally in 1904 as one of the excellent series of handbooks which, in addition to descriptive catalogues, are ~rovidedby the Berlin Museums for the guida,nce of visitors to their great collections. The haud- book of the Egyptian Religion seemed cspecially worthy of a wide circulation. It is a survey by the founder of the modern school of Egyptology in Germany, of perhaps tile most interest- ing of all the departments of this subject. The Egyptian religion appeals to some because of its endless variety of form, and the many phases of superstition and belief that it represents ; to others because of its early recognition of a high moral principle, its elaborate conceptions of a life aftcr death, and its connection with the development of Christianity; to others again no doubt because it explains pretty things dear to the collector of antiquities, and familiar objects in museums. Professor Erman is the first to present the Egyptian religion in historical perspective; and it is surely a merit in his worlc that out of his profound knowledge of the Egyptian texts, he permits them to tell their own tale almost in their own words, either by extracts or by summaries. -

Ancient Egyptian Chronology.Pdf

Ancient Egyptian Chronology HANDBOOK OF ORIENTAL STUDIES SECTION ONE THE NEAR AND MIDDLE EAST Ancient Near East Editor-in-Chief W. H. van Soldt Editors G. Beckman • C. Leitz • B. A. Levine P. Michalowski • P. Miglus Middle East R. S. O’Fahey • C. H. M. Versteegh VOLUME EIGHTY-THREE Ancient Egyptian Chronology Edited by Erik Hornung, Rolf Krauss, and David A. Warburton BRILL LEIDEN • BOSTON 2006 This book is printed on acid-free paper. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Ancient Egyptian chronology / edited by Erik Hornung, Rolf Krauss, and David A. Warburton; with the assistance of Marianne Eaton-Krauss. p. cm. — (Handbook of Oriental studies. Section 1, The Near and Middle East ; v. 83) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-90-04-11385-5 ISBN-10: 90-04-11385-1 1. Egypt—History—To 332 B.C.—Chronology. 2. Chronology, Egyptian. 3. Egypt—Antiquities. I. Hornung, Erik. II. Krauss, Rolf. III. Warburton, David. IV. Eaton-Krauss, Marianne. DT83.A6564 2006 932.002'02—dc22 2006049915 ISSN 0169-9423 ISBN-10 90 04 11385 1 ISBN-13 978 90 04 11385 5 © Copyright 2006 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill, Hotei Publishing, IDC Publishers, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, and VSP. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use is granted by Brill provided that the appropriate fees are paid directly to The Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Suite 910, Danvers, MA 01923, USA. -

Daf Ditty Eruvin 103- Papyrus As Bandage

Daf Ditty Eruvin 103: Papyrus, Bandaging, Despair The Soul has Bandaged moments The Soul has Bandaged moments - When too appalled to stir - She feels some ghastly Fright come up And stop to look at her - Salute her, with long fingers - Caress her freezing hair - Sip, Goblin, from the very lips The Lover - hovered - o'er - Unworthy, that a thought so mean Accost a Theme - so - fair - The soul has moments of escape - When bursting all the doors - She dances like a Bomb, abroad, And swings opon the Hours, As do the Bee - delirious borne - Long Dungeoned from his Rose - Touch Liberty - then know no more - But Noon, and Paradise The Soul's retaken moments - When, Felon led along, With shackles on the plumed feet, And staples, in the song, The Horror welcomes her, again, These, are not brayed of Tongue - EMILY DICKINSON 1 Her bandaged prison of depression or despair is truly a hell from which no words can escape, whether a call for help, a poem, or a prayer. 2 3 Rashi . שדקמ but not outside of the בש ת on שדקמה ב י ת may wrap a reed over his wound in the הכ ן A If he ימג יסמ - the ימג and, wound the heals פר ו הא תבשב ובש ת ה י א . ;explains, as the Gemara later says . אד ו ר י י את א י ס ו ר because it’s an , שדקמ in the סא ו ר is trying to draw out blood, it is even MISHNA: With regard to a priest who was injured on his finger on Shabbat, he may temporarily wrap it with a reed so that his wound is not visible while he is serving in the Temple. -

Paola Davoli

Papyri, Archaeology, and Modern History Paola Davoli I. Introduction: the cultural and legal context of the first discoveries. The evaluation and publication of papyri and ostraka often does not take account of the fact that these are archaeological objects. In fact, this notion tends to become of secondary importance compared to that of the text written on the papyrus, so much so that at times the questions of the document’s provenance and find context are not asked. The majority of publications of Greek papyri do not demonstrate any interest in archaeology, while the entire effort and study focus on deciphering, translating, and commenting on the text. Papyri and ostraka, principally in Greek, Latin, and Demotic, are considered the most interesting and important discoveries from Greco-Roman Egypt, since they transmit primary texts, both documentary and literary, which inform us about economic, social, and religious life in the period between the 4th century BCE and the 7th century CE. It is, therefore, clear why papyri are considered “objects” of special value, yet not archaeological objects to study within the sphere of their find context. This total decontextualization of papyri was a common practice until a few years ago though most modern papyrologists have by now fortunately realized how serious this methodological error is for their studies.[1] Collections of papyri composed of a few dozen or of thousands of pieces are held throughout Europe and in the United States. These were created principally between the end of the 19th century and the first half of the 20th century, a period in which thousands of papyri were sold in the antiquarian market in Cairo.[2] Greek papyri were acquired only sporadically and in fewer numbers until the first great lot of papyri arrived in Cairo around 1877. -

A Study in American Jewish Leadership

Cohen: Jacob H Schiff page i Jacob H. Schiff Cohen: Jacob H Schiff page ii blank DES: frontis is eps from PDF file and at 74% to fit print area. Cohen: Jacob H Schiff page iii Jacob H. Schiff A Study in American Jewish Leadership Naomi W. Cohen Published with the support of the Jewish Theological Seminary of America and the American Jewish Committee Brandeis University Press Published by University Press of New England Hanover and London Cohen: Jacob H Schiff page iv Brandeis University Press Published by University Press of New England, Hanover, NH 03755 © 1999 by Brandeis University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America 54321 UNIVERSITY PRESS OF NEW ENGLAND publishes books under its own imprint and is the publisher for Brandeis University Press, Dartmouth College, Middlebury College Press, University of New Hampshire, Tufts University, and Wesleyan University Press. library of congress cataloging-in-publication data Cohen, Naomi Wiener Jacob H. Schiff : a study in American Jewish leadership / by Naomi W. Cohen. p. cm. — (Brandeis series in American Jewish history, culture, and life) Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn 0-87451-948-9 (cl. : alk. paper) 1. Schiff, Jacob H. (Jacob Henry), 1847-1920. 2. Jews—United States Biography. 3. Jewish capitalists and financiers—United States—Biography. 4. Philanthropists—United States Biography. 5. Jews—United States—Politics and government. 6. United States Biography. I. Title. II. Series. e184.37.s37c64 1999 332'.092—dc21 [B] 99–30392 frontispiece Image of Jacob Henry Schiff. American Jewish Historical Society, Waltham, Massachusetts, and New York, New York. -

The Petrie Museum of 'Race' Archaeology?

Think Pieces: A Journal of the Joint Faculty Institute of Graduate Studies, University College London 1(0) ‘UCLfacesRACEISM: Past, Present, Future’ The Petrie Museum of 'Race' Archaeology? Debbie Challice [email protected] The essay makes the case that the Petrie Museum at UCL—a collection of objects from Egypt and Sudan comprising over 7,000 years of history from the Nile valley in northern Africa—is as much a museum of ‘race’ archaeology as Egyptian archaelogy. Tracing the relationship between slavery, racism and curatorial practices at museums, I excavate the lifelong beliefs of William Petrie in migration, racial mixing and skull measuring through objects such as the craniometer now housed at the Department of Statistical Sciences. The correlation of racialised groups and purported intelligence in Petrie’s work is examined, and I finally claim that his ideas need to be re-examined for an understanding of the Petrie Museum and their legacy within UCL today. ‘Race’, Archaeology, Museums, William Matthew Flinders Petrie, UCL Petrie Museum The Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology at University College London (UCL) is made up of a collection of 80,000 objects from Egypt and Sudan that comprise over 7,000 years of history from the Nile valley in northern Africa. The museum is celebrated for its combination of objects, excavation and archival records, which give a unique insight into the ancient context of the collection as well as the work of the museum’s founding archaeologist William Matthew Flinders Petrie (1853-1942). These records also give an insight into the racially determinist viewpoints of Petrie and how he interpreted some of the objects in the museum according to ideas about race in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. -

How Ancient Egypt Became Common Knowledge to Britons, 1870-1922

“The Glamour of Egypt Possesses Us”: How Ancient Egypt Became Common Knowledge to Britons, 1870-1922 Holly Polish A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Arts in History Professor Katharine Norris, Faculty Director American University May 2009 Polish 1 Fun , a comedy magazine, reported on the 1896 “discovery” of an important papyrus, found in Egypt. 1 The papyrus depicts ancient Egyptians playing golf and wearing kilts and tams. It is a parody of paintings with which many are familiar, those in which figures are drawn alongside hieroglyphs relating a story. The included caption reports that the papyrus was examined by “experts on Egyptian matters” who “have all agreed that it deals, if not with golf itself, at least with a game of remarkable similarity.” 2 The writer continues and suggests that Scotland may want to reconsider its claim to the pastime. In that brief caption, the writer raises the point that the public relies on the work of “the Professor” and “experts on Egyptian matters” to decipher the ancient culture, and, furthermore, to decipher the origins of their own heritage. The satirist’s work depends on the British public’s familiarity with ancient Egyptian art and expression to be able to understand the joke. The parody in Fun was conceived in the context of an exciting period for study of Egypt, the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. While travelers, scholars, and archaeologists developed precise methodology and were able to travel more easily, the study of Egypt, took on the title Egyptology and, like many disciplines, became formalized. -

Bulletin De L'institut Français D'archéologie Orientale

MINISTÈRE DE L'ÉDUCATION NATIONALE, DE L'ENSEIGNEMENT SUPÉRIEUR ET DE LA RECHERCHE BULLETIN DE L’INSTITUT FRANÇAIS D’ARCHÉOLOGIE ORIENTALE en ligne en ligne en ligne en ligne en ligne en ligne en ligne en ligne en ligne en ligne BIFAO 114 (2014), p. 455-518 Nico Staring The Tomb of Ptahmose, Mayor of Memphis Analysis of an Early 19 th Dynasty Funerary Monument at Saqqara Conditions d’utilisation L’utilisation du contenu de ce site est limitée à un usage personnel et non commercial. Toute autre utilisation du site et de son contenu est soumise à une autorisation préalable de l’éditeur (contact AT ifao.egnet.net). Le copyright est conservé par l’éditeur (Ifao). Conditions of Use You may use content in this website only for your personal, noncommercial use. Any further use of this website and its content is forbidden, unless you have obtained prior permission from the publisher (contact AT ifao.egnet.net). The copyright is retained by the publisher (Ifao). Dernières publications 9782724708288 BIFAO 121 9782724708424 Bulletin archéologique des Écoles françaises à l'étranger (BAEFE) 9782724707878 Questionner le sphinx Philippe Collombert (éd.), Laurent Coulon (éd.), Ivan Guermeur (éd.), Christophe Thiers (éd.) 9782724708295 Bulletin de liaison de la céramique égyptienne 30 Sylvie Marchand (éd.) 9782724708356 Dendara. La Porte d'Horus Sylvie Cauville 9782724707953 Dendara. La Porte d’Horus Sylvie Cauville 9782724708394 Dendara. La Porte d'Hathor Sylvie Cauville 9782724708011 MIDEO 36 Emmanuel Pisani (éd.), Dennis Halft (éd.) © Institut français d’archéologie orientale - Le Caire Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org) 1 / 1 The Tomb of Ptahmose, Mayor of Memphis Analysis of an Early 19 th Dynasty Funerary Monument at Saqqara nico staring* Introduction In 2005 the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, acquired a photograph taken by French Egyptologist Théodule Devéria (fig.