What Has Pragmatism to Offer Law?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jus Cogens As a Vision of the International Legal Order Dr

Penn State International Law Review Volume 29 Article 2 Number 2 Penn State International Law Review 9-1-2010 Jus Cogens as a Vision of the International Legal Order Dr. Markus Petsche Follow this and additional works at: http://elibrary.law.psu.edu/psilr Part of the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Petsche, Dr. Markus (2010) "Jus Cogens as a Vision of the International Legal Order," Penn State International Law Review: Vol. 29: No. 2, Article 2. Available at: http://elibrary.law.psu.edu/psilr/vol29/iss2/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Penn State Law eLibrary. It has been accepted for inclusion in Penn State International Law Review by an authorized administrator of Penn State Law eLibrary. For more information, please contact [email protected]. I Articles I Jus Cogens as a Vision of the International Legal Order Dr. Markus Petsche* Table of Contents INTRODUCTION .............................................. 235 I. THE INAPPROPRIATENESS OF CHARACTERIZING JUS COGENS AS A RULE OF INTERNATIONAL LAW AND THE LIMITED RELEVANCE OF JUS COGENS FOR THE PRACTICE OF INTERNATIONAL LAW...................................238 A. FundamentalConceptual and Theoretical Flaws ofJus Cogens .................................... 238 1. Origins of Jus Cogens. .................. ..... 238 2. Jus Cogens as a Set of Norms Lacking Substance........ 242 3. Jus Cogens as a Set of Norms Lacking a Procedure for Its Determination. ............ ......... .......... 243 4. Jus Cogens as a Set of Norms Lacking a Proper Theoretical Basis.......................... 245 B. The Limited Relevance of Jus Cogens for the Law of Treaties: Rare and Unsuccessful Reliance on Jus * DEA (Paris 1); LL.M. (NYU); Ph.D. -

Gifts Basket for Professor Grzegorz W. Kolodko

„Ekonomista” 2019, nr 3 http://www.ekonomista.info.pl KONFERENCJE I SEMINARIA ANDRZEJ K. KOŹMIŃSKI* Gifts Basket for Professor Grzegorz W. Kolodko We are celebrating here two important anniversaries: Kozminski University’s 25th and Professor Grzegorz W. Kolodko’s 70th birthday. They are both young and hopeful. But Professor Kolodko seems younger. This is at least my impression when I try to follow his countless activities spanning around the globe. Birthdays are gifts’ time. Professor Kolodko has found by his bed two sizable baskets of gifts: one international and one Polish. In principle all the donors volunteered to bring their gifts personally. Unfortunately, some were hounded by bad luck with health prob- lems like Nuti, Galbraith Jr. or Phelps, others had to give priority to meetings with the highest authorities like Prof. Lin meeting President Xi exactly at this time, or to the call of duty like Saul Estrin who has a lecture at LSE. However, all the missing and missed contributors prepared videos, which will be shown and will be referred to in our debate. Because I do hope for a lively debate, you are all invited to. Today we are permitted to peep into the international baskets: special issue of Acta Oeconomica dedicated to Pro- fessor Kolodko and debate will be conducted in English. Tomorrow will be the Polish day referring to the sumptuous volume of 28 essays by top notch Polish economists, just of press by Polish Scientific publishers. To kick off our today’s debate, let me share with you some impressions I had when reading through this unique collection of scientific papers edited with care by promi- nent journal affiliated to the Hungarian Academy of Sciences. -

Western Philosophy Rev

Designed by John Cornet, Phoenix HS (Ore) Western Philosophy rev. September 2012 The very process of philosophy has been a driving force in the tranformation of the world. From the figure who dwells upon how to achieve power, to the minister who contemplates the paradox of the only truth (their faith) yet which is also stagnent, to the astronomers who are searching the stars for signs of other civilizations, to the revolutionaries who sought to construct a national government which would protect the rights of the minority, the very exercise of philosophy and philosophical thought is at a core of human nature. Philosophy addresses what are sometimes called the "big questions." These include questions of morality and ethics, ideology/faith,, politics, the truth of knowledge, the nature of reality, and the meaning of human existance (...just to name a few!) (Religion addresses some of the same questions, but while philosophy and religion overlap in some questions, they can and do differ significantly in the approach they take to answering them.) Subject Learning Outcomes Skills-Based Learning Outcomes Behavioral Expectations and Grading Policy Develop an appreciation for and enjoyment of Organize, maintain and learn how to study from a learning, particularly in how learning should subject-specific notebook Attendance, participation and cause us to question what we think we know Be able to demonstrate how to take notes (including being prepared are daily and have a willingness to entertain new utilizing two-column format) expectations perspectives on issues. Be able to engage in meaningful, substantive discussion A classroom culture of respect and Students will develop familiarity with major with others. -

Indigenous and Tribal People's Rights Over Their Ancestral Lands

INTER‐AMERICAN COMMISSION ON HUMAN RIGHTS OEA/Ser.L/V/II. Doc. 56/09 30 December 2009 Original: Spanish INDIGENOUS AND TRIBAL PEOPLES’ RIGHTS OVER THEIR ANCESTRAL LANDS AND NATURAL RESOURCES Norms and Jurisprudence of the Inter‐American Human Rights System 2010 Internet: http://www.cidh.org E‐mail: [email protected] OAS Cataloging‐in‐Publication Data Derechos de los pueblos indígenas y tribales sobre sus tierras ancestrales y recursos naturales: Normas y jurisprudencia del sistema interamericano de derechos humanos = Indigenous and tribal people’s rights over their ancestral lands and natural resources: Norms and jurisprudence of the Inter‐American human rights system / [Inter‐American Commission on Human Rights.] p. ; cm. (OEA documentos oficiales ; OEA/Ser.L)(OAS official records ; OEA/Ser.L) ISBN 978‐0‐8270‐5580‐3 1. Human rights‐‐America. 2. Indigenous peoples‐‐Civil rights‐‐America. 3. Indigenous peoples‐‐Land tenure‐‐America. 4. Indigenous peoples‐‐Legal status, laws, etc.‐‐America. 5. Natural resources‐‐Law and legislation‐‐America. I. Inter‐American Commission on Human Rights. II Series. III. Series. OAS official records ; OEA/Ser.L. OEA/Ser.L/V/II. Doc.56/09 Document published thanks to the financial support of Denmark and Spain Positions herein expressed are those of the Inter‐American Commission on Human Rights and do not reflect the views of Denmark or Spain Approved by the Inter‐American Commission on Human Rights on December 30, 2009 INTER‐AMERICAN COMMISSION ON HUMAN RIGHTS MEMBERS Luz Patricia Mejía Guerrero Víctor E. Abramovich Felipe González Sir Clare Kamau Roberts Paulo Sérgio Pinheiro Florentín Meléndez Paolo G. Carozza ****** Executive Secretary: Santiago A. -

The Virtue of Vulnerability

THE VIRTUE OF VULNERABILITY Nathalie Martin* My vulnerability to my own life is irrefutable. Nor do I wish it to be otherwise, As vulnerability is a guardian of integrity. Anne Truitt, sculptor and psychologist Ten years ago, vulnerability scholar Martha Fineman began examining how vulnerability connects us as human beings and what the universal human condition of vulnerability says about the obligations of the state to its institutions and individuals.1 Central to Fineman’s work is recognition that vulnerability is universal, constant, and inherent in the human condition.2 Fineman has spent the past decade examining how structures of our society will manage our common vulnerabilities, in hopes of using these vulnerabilities to move society toward a new vision of equality.3 While Fineman focuses on how vulnerability can transform society as a whole, here I examine the role of vulnerability in transforming individual relationships, particularly the attorney-client relationship. I argue that lawyers can benefit greatly by showing their vulnerabilities to clients. As a common syllogism goes, “All men are mortal. Socrates is a man. Therefore, Socrates is mortal.”4 Similarly, we could say that a particular * I am grateful for Nancy Huffstutler, who first brought the virtue of vulnerability into my conciseness, to my colleagues Jennifer Laws and Ernesto Longa for their fine research assistance, my friend John Brandt for teaching me what doctors know about vulnerability, for my friends Jenny Moore and Fred Hart, and my beautiful husband Stewart Paley. I also thank my wonderful editor, William Dietz. 1. Martha A. Fineman, The Vulnerable Subject: Anchoring Equality in the Human Condition, 20 YALE J.L. -

Rights, Respect, Responsibility: Don't Have Sex Without Them

Rights, Respect, Responsibility: Don’t Have Sex Without Them A Lesson Plan from Rights, Respect, Responsibility: A K-12 Curriculum Fostering responsibility by respecting young people’s rights to honest sexuality education. ADVANCE PREPARATION FOR LESSON: NSES ALIGNMENT: • Download the YouTube video on consent, “2 Minutes Will By the end of 12th grade, Change the Way You Think About Consent,” at https://www. students will be able to: youtube.com/watch?v=laMtr-rUEmY. HR.12.CC.3 – Define sexual consent and explain its • Also download the trailer for Pitch Perfect 2 - The Ellen Show implications for sexual decision- version (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KBwOYQd21TY), making. queuing it up to play a brief clip between 2:10 and 2:27. PS.12.CC.3 – Explain why using tricks, threats or coercion in • If you cannot download and save these to your desktop in relationships is wrong. advance, talk with your school’s IT person to ensure you have HR.12.INF.2 – Analyze factors, internet access to that link during class. including alcohol and other substances, that can affect the • Print out the skit scenarios and cut out each pair, making sure ability to give or perceive the the correct person 1 goes with the correct person 2. Determine provision of consent to sexual how many pairs there will be in your class and make several activity. copies of each scenario, enough for each pair to get one. TARGET GRADE: Grade 10 LEARNING OBJECTIVES: Lesson 1 By the end of this lesson, students will be able to: 1. -

METAPHYSICS and the WORLD CRISIS Victor B

METAPHYSICS AND THE WORLD CRISIS Victor B. Brezik, CSB (The Basilian Teacher, Vol. VI, No. 2, November, 1961) Several years ago on one of his visits to Toronto, M. Jacques Maritain, when he was informed that I was teaching a course in Metaphysics, turned to me and inquired with an obvious mixture of humor and irony indicated by a twinkle in the eyes: “Are there some students here interested in Metaphysics?” The implication was that he himself was finding fewer and fewer university students with such an interest. The full import of M. Maritain’s question did not dawn upon me until later. In fact, only recently did I examine it in a wider context and realize its bearing upon the present world situation. By a series of causes ranging from Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason in the 18th century and the rise of Positive Science in the 19th century, to the influence of Pragmatism, Logical Positivism and an absorbing preoccupation with technology in the 20th century, devotion to metaphysical studies has steadily waned in our universities. The fact that today so few voices are raised to deplore this trend is indicative of the desuetude into which Metaphysics has fallen. Indeed, a new school of philosophers, having come to regard the study of being as an entirely barren field, has chosen to concern itself with an analysis of the meaning of language. (Volume XXXIV of Proceedings of the American Catholic Philosophical Association deals with Analytical Philosophy.) Yet, paradoxically, while an increasing number of scholars seem to be losing serious interest in metaphysical studies, the world crisis we are experiencing today appears to be basically a crisis in Metaphysics. -

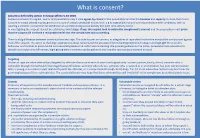

What Is Consent?

What is consent? Consent is defined by section 74 Sexual Offences Act 2003. Someone consents to vaginal, anal or oral penetration only if s/he agrees by choice to that penetration and has the freedom and capacity to make that choice. Consent to sexual activity may be given to one sort of sexual activity but not another, e.g.to vaginal but not anal sex or penetration with conditions, such as wearing a condom. Consent can be withdrawn at any time during sexual activity and each time activity occurs. In investigating the suspect, it must be established what steps, if any, the suspect took to obtain the complainant’s consent and the prosecution must prove that the suspect did not have a reasonable belief that the complainant was consenting. There is a big difference between consensual sex and rape. This aide focuses on consent, as allegations of rape often involve the word of the complainant against that of the suspect. The aim is to challenge assumptions about consent and the associated victim-blaming myths/stereotypes and highlight the suspect’s behaviour and motives to prove he did not reasonably believe the victim was consenting. We provide guidance to the police, prosecutors and advocates to identify and explain the differences, highlighting where evidence can be gathered and how the case can be presented in court. Targeting Victims of rape are often selected and targeted by offenders because of ease of access and opportunity - current partner, family, friend, someone who is vulnerable through mental health/ learning/physical difficulties, someone who sells sex, someone who is isolated or in an institution, has poor communication skills, is young, in a current or past relationship with the offender, or is compromised through drink/drugs. -

Introduction to Philosophy KRSN PHL1010 Institution Course ID

Introduction to Philosophy KRSN PHL1010 Institution Course ID Course Title Credit Hours Allen County CC HUM 125 Philosophy 3 Barton County CC Phil 1602 Introduction to Philosophy 3 Butler CC PL 290 Philosophy 1 3 Cloud County CC PH 100 Introduction to Philosophy 3 Coffeyville CC HUMN 104 Introduction to Philosophy 3 Colby CC Pl 101 Introduction to Philosophy 3 Cowley County CC PHO 6447 Introduction to Philosophy 3 Dodge City CC PHIL 201 Introduction to Philosophy 3 Fort Scott CC PH 1113 Philosophy of Life 3 Garden City CC PHIL 101 Introduction to Philosophy 3 Highland CC PHI 101 Introduction to Philosophy 3 Hutchinson CC PL 101 Introduction to Philosophy 3 Independence CC SOC2003 Introduction to Philosophy 3 Johnson County CC PHIL 121 Introduction to Philosophy 3 Kansas City KCC PHIL 0103 Introduction to Philosophy 3 Labette CC PHIL 101 Philosophy 1 3 Neosho County CC HUM 103 Introduction to Philosophy 3 Pratt CC PHL 130 Introduction to Philosophy 3 Seward County CC PH 2203 Introduction to Philosophy 3 Flint Hills TC Not Offered Not Offered Manhattan Area TC Not Offered Not Offered North Central KTC Not Offered Not Offered Northwest KTC Not Offered Not Offered Salina Area TC Not Offered Not Offered Wichita Area TC Not Offered Not Offered Emporia St. U. PI 225 Introduction to Philosophy 3 Fort Hays St. U. PHIL 120 Introduction to Philosophy 3 Kansas St. U. PHILO 100 Introduction to Philosophical Problems 3 Pittsburg St. U. PHIL 103 Introduction to Philosophy 3 U. Of Kansas PHIL 140 Introduction to Philosophy 3 Wichita St. -

PRAGMATISM and ITS IMPLICATIONS: Pragmatism Is A

PRAGMATISM AND ITS IMPLICATIONS: Pragmatism is a philosophy that has had its chief development in the United States, and it bears many of the characteristics of life on the American continent.. It is connected chiefly with the names of William James (1842-1910) and John Dewey. It has appeared under various names, the most prominent being pragmatism, instrumentalism, and experimentalism. While it has had its main development in America, similar ideas have been set forth in England by Arthur Balfour and by F. C. S. Schiller, and in Germany by Hans Vaihingen. WHAT PRAGMATISM IS Pragmatism is an attitude, a method, and a philosophy which places emphasis upon the practical and the useful or upon that which has satisfactory consequences. The term pragmatism comes from a Greek word pragma, meaning "a thing done," a fact, that which is practical or matter-of-fact. Pragmatism uses the practical consequences of ideas and beliefs as a standard for determining their value and truth. William James defined pragmatism as "the attitude of looking away from first things, principles, 'categories,' supposed necessities; and of looking towards last things, fruits, consequences, facts." Pragmatism places greater emphasis upon method and attitude than upon a system of philosophical doctrine. It is the method of experimental inquiry carried into all realms of human experience. Pragmatism is the modern scientific method taken as the basis of a philosophy. Its affinity is with the biological and social sciences, however, rather than with the mathematical and physical sciences. The pragmatists are critical of the systems of philosophy as set forth in the past. -

Holmes, Cardozo, and the Legal Realists: Early Incarnations of Legal Pragmatism and Enterprise Liability

Holmes, Cardozo, and the Legal Realists: Early Incarnations of Legal Pragmatism and Enterprise Liability EDMUND URSIN* TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................. 538 II. SETTING THE STAGE: TORT AND CONSTITUTIONAL LAW AT THE TURN OF THE TWENTIETH CENTURY ............................................................................ 545 III. HOLMES AND THE PATH OF THE LAW ................................................................. 550 A. Holmes and the Need for Judicial Creativity in Common Law Subjects ............................................................................................ 550 B. The Path Not Followed ............................................................................ 554 IV. THE INDUSTRIAL ACCIDENT CRISIS, THE WORKERS’ COMPENSATION SOLUTION, AND A CONSTITUTIONAL CONFRONTATION ....................................... 558 A. The Industrial Accident Crisis and the Workers’ Compensation Solution ............................................................................ 558 * © 2013 Edmund Ursin. Professor of Law, University of San Diego School of Law. Thanks to Richard Posner for valuable comments on an earlier draft of this Article and to Roy Brooks and Kevin Cole for always helpful comments on previous articles upon which I expand in this Article. See Edmund Ursin, Clarifying the Normative Dimension of Legal Realism: The Example of Holmes’s The Path of the Law, 49 SAN DIEGO L. REV. 487 (2012) [hereinafter Ursin, Clarifying]; -

Rules of Law, Laws of Science

Rules of Law, Laws of Science Wai Chee Dimock* My Essay is a response to legal realism,' to its well-known arguments against "rules of law." Legal realism, seeing itself as an empirical practice, was not convinced that there could be any set of rules, formalized on the grounds of logic, that would have a clear determinative power on the course of legal action or, more narrowly, on the outcome of litigated cases. The decisions made inside the courtroom-the mental processes of judges and juries-are supposedly guided by rules. Realists argued that they are actually guided by a combination of factors, some social and some idiosyncratic, harnessed to no set protocol. They are not subject to the generalizability and predictability that legal rules presuppose. That very presupposition, realists said, creates a gap, a vexing lack of correspondence, between the language of the law and the world it purports to describe. As a formal system, law operates as a propositional universe made up of highly technical terms--estoppel, surety, laches, due process, and others-accompanied by a set of rules governing their operation. Law is essentially definitional in this sense: It comes into being through the specialized meanings of words. The logical relations between these specialized meanings give it an internal order, a way to classify cases into actionable categories. These categories, because they are definitionally derived, are answerable only to their internal logic, not to the specific features of actual disputes. They capture those specific features only imperfectly, sometimes not at all. They are integral and unassailable, but hollowly so.