Dawn Lyon Billingsgate Paper for SRO Corrected August 2016.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

10. Taipei Fish Market 9. Aberdeen Seafood

10. Taipei Fish Market Location: Taipei, Taiwan Teipei Fish Market is among the major fish markets in China. It is located in the Zhongshan District of Teipie- the capital of Taiwan. Chinese are fond of eating seafood. The Chinese cuisine contains variety of sea food. The best seafood of China is supplied by this market. After serving the needs of local population the seafood is also exported to great measure. The Market is being maintained by some of the large commercial group so it has made its way to being in the top fish markets of the world. 9. Aberdeen Seafood Location: Aberdeen, Hong Kong 9. Aberdeen seafood is a famous fish Market of Hong Kong Island. As the Market is placed on an Island, it provides a diverse range of seafood. Aberdeen being a small village in Hong Kong attracts a lot of travellers every year and that creates a huge demand for seafood. Local People in Aberdeen usually spend their days on the boats catching the fishes and earning their livelihood. To meet their need and to cater to visitors cafes are set up on the boats which serve excellent sea-food. 8. Fulton Fish Market Location: New York, USA The Fulton Fish Market is located in Bronx, New York. The Market was originally a part of The Fulton Market which was a place for selling a varied of food and edible stuff. The fish Market section was later relocated in 2005 to Bronx. Now it is known as Fulton fish Market and is among the oldest fish markets of America. -

Britain's Distant Water Fishing Industry, 1830-1914

BRITAIN'S DISTANT WATER FISHING INDUSTRY, 1830-1914 A STUDY IN TECHNOLOGICAL CHANGE being a Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the University of Hull by MICHAEL STUART HAINES APRIL 1998 CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 4 LIST OF TABLES 5 INTRODUCTION 12 i THE THESIS 14 ii CONTEXT 15 iii SOURCES AND METHODOLOGY 19 PART ONE THE ECONOMIC CONTEXT OF TECHNOLOGICAL CHANGE 28 CHAPTER 1 THE FISH TRADE 29 i FISH AND THE FISHERIES 29 ii DEVELOPMENT OF THE FISHING INDUSTRY TO 1830 37 iii LATENT DEMAND 44 CHAPTER 2 DISTRIBUTION 50 i INLAND TRANSPORT 50 ii PORT INFRASTRUCTURE 68 iii ACTUAL DEMAND 78 PART TWO TECHNOLOGICAL CHANGE AND FISH PRODUCTION 84 CHAPTER 3 SAIL 85 i TRAWLING 85 ii SMACKS 96 iii ICE 118 iv STEAM AND SMACKS 127 CHAPTER 4 EARLY STEAMERS 134 i EXPERIMENTS AND TUGS 134 ii STEAM FISHING BOATS 143 CHAPTER 5 DEVELOPMENTS AFTER 1894 182 i THE OTTER-TRAWL 182 ii DEMERSAL FISHERIES 188 iii PELAGIC FISHERIES 198 iv MOTORS AND WIRELESSES 211 PART THREE RAMIFICATIONS OF TECHNOLOGICAL CHANGE 217 CHAPTER 6 THE INDUSTRY 218 i BUSINESS ORGANIZATION 218 ii HUMAN RESOURCES 233 CHAPTER 7 EXTERNAL FORCES 259 i EUROPEAN FISHING INDUSTRIES 259 ii PERCEPTIONS OF THE FISHERIES 274 iii LEGACY 288 PART FOUR BIBLIOGRAPHY 294 PART FIVE APPENDIX 306 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank the National Fishing Heritage Centre, Great Grimsby, for providing funds that enabled completion of this thesis. All the work was done from the University of Hull, and my gratitude is extended to the secretarial staff of the History Department and Kevin Watson for help with various practical matters, together with staff at the Brynmor Jones Library and Graduate Research Institute. -

Entertext Volume 8 ABSTRACTS

EnterText 8 EnterText Volume 8 ABSTRACTS Susan Ash Dr Barnardo and ‘The Queen’s Shades’: Liminal London, Hospitality and Victorian Child Rescue To support his ubiquitous philanthropic enterprises, Dr. Barnardo published autobiographical tales of child rescue set in the typical London spaces where the homeless ‘city arabs’ often took shelter: lodging houses, stairwells, archways and bridges. This essay examines two texts that depict a site known as ‘The Queen’s Shades,’ a ‘doss’ created by discarded boxes and detritus near Billingsgate Fish Market. In Our Father’s Sparrow, Barnardo gently fictionalises this location to create a story about hospitality among street children. In contrast, his version of ‘The Shades’ in ‘God’s Own Hand’ (an account of his early career) exemplifies monstrous corporeal and architectural collapse. I argue that Barnardo’s conflation of human sensations with architectural detritus denigrates maternity while justifying the ‘right’ reformer’s permeation into the poorest classes. I incorporate Derrida’s work on thresholds and hospitality to explore how ‘The Shades,’ neither inside nor outside any fixed architectural structure, opens up discussion about ‘liminal London’. Peter Coles and Gesche Würfel London-Luton: A Photographic Exploration of the Lea Valley Using photography, interviews and documentary research, this study examines various boundaries within the Lea River Valley, from its source to the estuary on the Thames. The work partly builds on a previous study by one of the authors on the 2012 Olympic Abstracts 12 EnterText 8 site, before construction work began and the area was closed to the public. The study also incorporates a reflection on the Meridian, which bisects a vertical stretch of the Lea from the Thames to Ware. -

Sustainable Seafood Coalition (SSC) Labelling Working Group Minutes

Sustainable Seafood Coalition (SSC) Labelling Working Group minutes Date: 8 May, 2013 Location: Billingsgate Seafood School, Billingsgate Fish Market, 1 Old Billingsgate Walk, 16 Lower Thames St, London EC3R 6DX Number of attendees: 14 total including members, non-member experts and 3 ClientEarth staff (acting as facilitator, secretariat - minute taker, and secretariat - presenter) Summary of agreed points: In order to make a claim of responsibility for fish that have been risk assessed and come out as high or medium risk, the guidance document should recommend that the following steps be taken (in addition to the AIPCE-CEP principles): 1. Engagement in the Fishery/Aquaculture Improvement Project (FIP/AIP) should be relative to the size of the business; 2. The Member should communicate externally their business' role and work in engaging with the Fishery/Aquaculture Improvement Project; 3. The member should be transparent about the commitment the business is making, the goal, and how it will be achieved; 4. Member should ensure their business has accurate and up-to-date documentation to prove their engagement; 5. Members should commit to a timeframe for achieving milestones within the FIP/AIP engagement; and 6. Members should review progress of the projects regularly. The guidance document should provide use examples and case studies of existing and past FIP/AIPs, along with references to other organisations’ work on FIPs and AIPs. NB: The agenda was not followed as had been set out prior to the meeting, but many of the relevant issues were covered and are outlined below. The Sustainable Seafood Coalition (SSC) Labelling working group minutes: 8 May 2013 Purpose of the meeting 1. -

Billingsgate Market the UK’S LARGEST INLAND FISH MARKET BJ

BILLINGSGATE MARKET THE UK’S LARGEST INLAND FISH MARKET BJ Bennett (Billingsgate) Ltd is one of the UK’s the quality of our product, the e ciency of our deliveries leading sh wholesalers specialising in and the customer care provided by our sta , has ensured salmon, exotics, farmed sh, freshwater sh that J.Bennett continues to thrive in an ever-competitive market. and indigenous prime species. London’s leading wholesale fi sh merchants The company has a sta of 30 dedicated to supplying J.Bennett has been established over one hundred excellent quality and good service. They are proud of Shop No.24 • O ce No.10 years and is a leader in it’s eld, sourcing product J. Bennett’s 100-plus year tradition and are happy to work worldwide with a reputation second to none. hard to maintain the standards that have taken J.Bennetts Billingsgate Market, Trafalgar Way, Poplar, London E14 5ST to the top of the fresh sh wholesale business. We plan to stay there for another 100 years at least. Tel : 020 7515 6007 Fax: 020 7987 8957 The company supplies the majority of caterers, retailers, E-Mail: [email protected] processors and salmon smokers in the UK, and can supply products anywhere in the UK in perfect chilled condition. J.Bennett Ltd We are one of the country’s largest suppliers of fresh O ce 10 salmon, supplying throughout the British Isles ad Europe. Billingsgate Market We deal in farmed, organic and wild salmon. Trafalgar Way Poplar The company was founded by John Bennett and remained London a family business until going public and becoming England Associated Fisheries in the late 1950s. -

Future of the Existing Sites

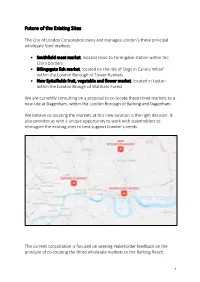

Future of the Existing Sites The City of London Corporation owns and manages London’s three principal wholesale food markets: • Smithfield meat market, located close to Farringdon station within the City’s borders • Billingsgate fish market, located on the Isle of Dogs in Canary Wharf within the London Borough of Tower Hamlets • New Spitalfields fruit, vegetable and flower market, located in Leyton within the London Brough of Waltham Forest We are currently consulting on a proposal to co-locate these three markets to a new site at Dagenham, within the London Borough of Barking and Dagenham. We believe co-locating the markets at this new location is the right decision. It also provides us with a unique opportunity to work with stakeholders to reimagine the existing sites to best support London’s needs. The current consultation is focused on seeking stakeholder feedback on the principle of co-locating the three wholesale markets to the Barking Reach, 1 Dagenham site. However, in the future, the City will be talking with stakeholders on exciting plans to incorporate the Smithfield site into the Culture Mile and we will be working with the Boroughs where the other two markets are currently located to communicate the future of these sites too. See below for more information about the existing market sites. Smithfield – Background Smithfield meat market was constructed in 1866-1867 to designs by Sir Horace Jones for the City Corporation. It is an important early Victorian market building and an exemplar of the type, with architectural and historical importance. The meat market is grade II* listed and is located within the Smithfield Conservation Area. -

An Assessment of Seafood Quality Certification Systems for World-Best-Practice Sustainable Production in Australia

International Specialised Skills Institute Inc An Assessment of Seafood Quality Certification Systems for World-Best-Practice Sustainable Production in Australia David O’Sullivan International ISS Institute/DEEWR Trades Fellowship Fellowship supported by the Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations, Australian Government t0 01 A 01 E ISS Institute Inc. 2009 © International Specialised Skills Institute ISS Institute Suite 101 685 Burke Road Camberwell Vic AUSTRALIA 3124 Telephone 03 9882 0055 Facsimile 03 9882 9866 Email [email protected] Web www.issinstitute.org.au Published by International Specialised Skills Institute, Melbourne. ISS Institute 101/685 Burke Road Camberwell 3124 AUSTRALIA Also extract published on www.issinstitute.org.au © Copyright ISS Institute 2009 This publication is copyright. No part may be reproduced by any process except in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. This project is funded by the Australian Government under the Strategic Intervention Program which supports the National Skills Shortages Strategy. This Fellowship was funded by the Australian Government through the Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations. The views and opinions expressed in the documents are those of the Authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Australian Government Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations. Whilst this report has been accepted by ISS Institute, ISS Institute cannot provide expert peer review of the report, and except as may be required by law no responsibility can be accepted by ISS Institute for the content of the report, or omissions, typographical, print or photographic errors, or inaccuracies that may occur after publication or otherwise. -

Influencing Canadian Seal Hunt Policy with a Consumer Boycott of Canadian Seafood

Influencing Canadian Seal Hunt Policy With a Consumer Boycott of Canadian Seafood prepared for The Directors of Animal Alliance of Canada & Environment Voters Prepared By Stephen Best August 2004 Stephen Best (519) 925‐3440 PO Box 988, (519) 925‐2003 Shelburne ON, Canada p (519) 940‐6222 L0N 1S0 [email protected] http://stephenbest.ca Influencing Canadian Seal Hunt Policy with a Consumer Boycott of Canadian Seafood Table of Contents Introduction ...................................................................................................................... 1 Why Canadian Seafood?................................................................................................. 4 The Efficacy of Consumer Boycotts............................................................................... 6 Economics of a Consumer Boycott................................................................................ 8 The Susceptibility of Canadian Seal Hunt Policy to a Consumer Boycott .................................................................................................... 9 The Susceptibility of the Canadian Fishing Industry to a Consumer Boycott .................................................................................................. 12 Anticipated Effect of a Canadian Seafood Boycott on Canadian Sealing Policy and the Sealing Industry.............................................. 14 Avoiding the Canadian Seafood Boycott ................................................................... 20 The Canadian Seafood to Boycott............................................................................... -

EPS Fish Box Collection at Billingsgate Fishmarket

CONTRIBUTIONS TO CASE STUDY A CIRCULAR ECONOMY RECYCLING #8 LONDON BILLINGSGATE FISH MARKET IS TURNING WASTE INTO REVENUE • The fi sh box market is the largest packaging appli- cation of expanded polystyrene (EPS) in Europe. • The material protects the 657,000 tonnes of fi sh landed at UK ports and fi sh farms every year. • On-site recycling of fi sh boxes at Billingsgate fi sh market in London has proven to be a viable com- mercial enterprise for a local waste and recycling company. DESCRIPTION Billingsgate fi sh market in London is the largest inland fi sh market in the UK. Regent Hill, a waste management and recycling company, takes advantage of the large amount of used fi sh boxes occurring at the market place. In Billingsgate market, the compaction element is located centrally and is easily acces- sible for all fi sh traders. The compacted material blocks are passed on to companies that convert the recyclable material to a usable compound. The new material is then used for manufacturing new products – in the case of the material sourced in Billings- gate, its insulation boards. Recycling works because the outlay for the machines is more than covered by the savings in disposal costs and by generated revenue. CONTRIBUTION TO A CIRCULAR ECONOMY On-site recycling at the fi sh market not only saves resources for collection and trans- portation of waste material, but also provides a closed-loop system to produce recy- cled material for the construction industry. PARTNERS Regent Hill, London Billingsgate Market “By introducing innovative and dedicated EPS recycling technology at the source of the waste, we have been able to increase our recycling rates and remove EPS from the landfi ll route. -

Billingsgate Fish Market Manager Jailed for 32 Months for £95,000 Theft

Appendix 1: London Evening Standard Report Billingsgate Fish Market manager jailed for 32 months for £95,000 theft Tristan Kirk Tuesday 3 May 2016 14 Desperate: Roshan Persad tried to blame the losses on the G4S security firm Central News The manager of London’s historic Billingsgate Fish Market who stole nearly £95,000 from traders’ rent to feed his gambling addiction has been jailed for two years and eight months. Roshan Persad, 48, stole the money from the market’s landlord over an 18-month period. He tried to shuffle funds around the market’s accounts to hide the missing sums, logging thousands of pounds of credit notes from traders to make it seem as though they were in arrears. Persad even suggested G4S guards had lost the cash while transporting it to the bank. Persad, from Hornchurch in Essex, denied the charges but a jury at the Old Bailey found him guilty of six counts of theft, seven of false accounting and one of fraud by abuse of position. Recorder Karim Khalil QC, sentencing, said: “You used the money to fund your gambling habit, which was far worse than you were prepared to admit. “As the losses mounted, you were left with few options: pay back the money from other sources, confess to your employers and seek support, or cover up the losses and hope no one would identify you as the thief — you chose the latter course.” Appendix 1: London Evening Standard Report Persad, who was employed by the City of London Corporation, started dipping into the accounts in March 2011. -

Sustainable Fishing Industry Well Supported by Recyclable EPS Fish Boxes

Sustainable fishing industry well supported by recyclable EPS fish boxes EPS or Expanded Polystyrene is a very light material made of 98% air and 2% polystyrene. Thanks to its unique properties, it has been preferred for over 50 years in multiple applications including fish boxes. It is approved for direct food contact both in the EU and the USA. Every day millions of EPS fish boxes travel across the world to deliver fresh fish safely to retailers. EPS fish boxes are generally used on a business-to-business basis: fish farmers use them to support the logistics of the fishing industry. Fish from fish farms and fish landed in the harbours are transported to processors using energy saving, hygienic, stable, easy-to-handle EPS fish boxes; processors then deliver them to fish mongers, markets and retailers, a well-established supply chain that can deliver fresh fish over long distances without any downgrade or food waste. The delicate nature of seafood presents a cold chain challenge. Fresh, chilled, frozen, and processed fishery products are transported all over the world. Therefore the decisive unique performance characteristic of the EPS fish box is its thermal insulating property. International regulatory measures require food industry and food professionals to comply with strict temperature requirements to protect food from contamination and preserve its hygienic condition. Spoilage can be controlled to a great degree: maintaining fish at the right temperature from packing until delivery ensures optimum safety, freshness and reduces food losses. Here EPS performs at its best. It is recognised as the optimal solution for thermal performance, impact resistance and excellent sustainability attributes (1) (2). -

Pirate Fish on Your Plate

Pirate Fish on Your Plate Tracking illegally-caught fsh from West Africa into the European market A report by the Environmental Justice Foundation ACKNoWlEDGMENTs This report was researched, written and produced by 5 st Peter’s st, london N1 8JD, UK the Environmental Justice Foundation. Tel 44 (0) 20 7359 0440 Design Alyson McCulloch ([email protected]) Fax 44 (0) 20 7359 7123 [email protected] Cover Image © simon Wheeler www.ejfoundation.org Printed on 100% post-consumer waste paper. The Environmental Justice Foundation is a UK-based non-governmental organisation working internationally. Thanks to Brian Emmerson and all at Emmerson Press for continued support. www.emmersonpress.co.uk More information about EJF’s work and pdf versions of this report can be found at www.ejfoundation.org EJF would like to thank the following people and their organisations for the invaluable time and assistance with Comments on the report, requests for further copies information, ideas and visual materials used in this report: or specifc queries about EJF should be directed to [email protected] Greenpeace International; Ministry for Fisheries and Aquaculture of Guinea; West Africa surveillance operations Coordination This document should be cited as: EJF (2007) Unit (soCU); Michael Earle; David Hammerstein MEP. Pirate Fish on your Plate – Tracking illegally-caught fsh from West Africa into the European market. In thanking these individuals, we in no way imply that they Environmental Justice Foundation, london, UK. or their organisations endorse the report’s content. IsBN No. 1-904523-12-9 EJF’s marine campaign is generously supported by the rufford Maurice laing Foundation In addition to the illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fshing that occurs in West African waters, a signifcant amount of IUU fshing is carried out by EU vessels and/or companies on the high seas, as well as within the territorial waters of both European and developing states.