Japanese American Internment and the Long Arc of Academic Freedom

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Choose Your Words Describing the Japanese Experience During WWII

Choose your Words Describing the Japanese Experience During WWII Dee Anne Squire, Wasatch Range Writing Project Summary: Students will use discussion, critical thinking, viewing, research, and writing to study the topic of the Japanese Relocation during WWII. This lesson will focus on the words used to describe this event and the way those words influence opinions about the event. Objectives: • Students will be able to identify the impact of World War II on the Japanese in America. • Students will write arguments to support their claims based on valid reasoning and evidence. • Students will be able to interpret words and phrases within video clips and historical contexts. They will discuss the connotative and denotative meanings of words and how those word choices shaped the opinion of Americans about the Japanese immigrants in America. • Students will use point of view to shape the content and style of their writing. Context: Grades 7-12, with the depth of the discussion changing based on age and ability Materials: • Word strips on cardstock placed around the classroom • Internet access • Capability to show YouTube videos Time Span: Two to three 50-minute class periods depending on your choice of activities. Some time at home for students to do research is a possibility. Procedures: Day 1 1. Post the following words on cardstock strips throughout the room: Relocation, Evacuation, Forced Removal, Internees, Prisoners, Non-Aliens, Citizens, Concentration Camps, Assembly Centers, Pioneer Communities, Relocation Center, and Internment Camp. 2. Organize students into groups of three or four and have each group gather a few words from the walls. -

Eleanor Roosevelt's Servant Leadership

Tabors: A Voice for the "Least of These:" Eleanor Roosevelt's Servant Le Servant Leadership: Theory & Practice Volume 5, Issue 1, 13-24 Spring 2018 A Voice for the “Least of These:” Eleanor Roosevelt’s Servant Leadership Christy Tabors, Hardin-Simmons University Abstract Greenleaf (2002/1977), the source of the term “servant leadership,” acknowledges a lack of nurturing or caring leaders in all types of modern organizations. Leaders and potential future leaders in today’s society need servant leader role-models they can study in order to develop their own servant leadership. In this paper, the author explores Eleanor Roosevelt’s life using Spears’ (2010) ten characteristics of servant leadership as an analytical lens and determines that Roosevelt functioned as a servant leader throughout her lifetime. The author argues that Eleanor Roosevelt’s servant leadership functions as a timeless model for leaders in modern society. Currently, a lack of literature exploring the direct link between Eleanor Roosevelt and servant leadership exists. The author hopes to fill in this gap and encourage others to contribute to this area of study further. Overall, this paper aims at providing practical information for leaders, particularly educational leaders, to utilize in their development of servant leadership, in addition to arguing why Eleanor Roosevelt serves as a model to study further in the field of servant leadership. Keywords: Servant Leadership, Leadership, Educational Leadership, Eleanor Roosevelt © 2018 D. Abbott Turner College of Business. SLTP. 5(1), 13-24 Published by CSU ePress, 2017 1 Servant Leadership: Theory & Practice, Vol. 5 [2017], Iss. 1, Art. 2 14 TABORS Eleanor Roosevelt, often remembered as Franklin D. -

Collection Highlights Since Its Founding in 1924, the Kalamazoo Institute of Arts Has Built a Collection of Nearly 5,000 Artworks

Collection Highlights Since its founding in 1924, the Kalamazoo Institute of Arts has built a collection of nearly 5,000 artworks. Enjoy an in-depth exploration of a selection of those artworks acquired by gift, bequest, or purchase support by special donors, as written by staff curators and guest editors over the years. Table of Contents KENOJUAK ASHEVAK Kenojuak Ashevak (ken-OH-jew-ack ASH-uh-vac), one of the most well-known Inuit artists, was a pioneering force in modern Inuit art. Ashevak grew up in a semi-nomadic hunting family and made art in various forms in her youth. However, in the 1950s, she began creating prints. In 1964, Ashevak was the subject of the Oscar-nominated documentary, Eskimo* Artist: Kenojuak, which brought her and her artwork to Canada’s—and the world’s—attention. Ashevak was also one of the most successful members of the Kinngait Co-operative, also known as the West Baffin Eskimo Co-operative, established in 1959 by James Houston, a Canadian artist and arts administrator, and Kananginak Pootoogook (ka-nang-uh-nak poo-to-guk), an Inuit artist. The purpose of the co-operative is the same as when it was founded—to raise awareness of Inuit art and ensure indigenous artists are compensated appropriately for their work in the Canadian (and global) art market. Ashevak’s signature style typically featured a single animal on a white background. Inspired by the local flora and fauna of the Arctic, Ashevak used bold colors to create dynamic, abstract, and stylized images that are devoid of a setting or fine details. -

November 5, 2009

ATTACHMENT 2 L ANDMARKSLPC 01-07-10 Page 1 of 18 P RESERVATION C OMMISSION Notice of Decision MEETING OF: November 5, 2009 Property Address: 2525 Telegraph Avenue (2512-16 Regent Street) APN: 055-1839-005 Also Known As: Needham/Obata Building Action: Landmark Designation Application Number: LM #09-40000004 Designation Author(s): Donna Graves with Anny Su, John S. English, and Steve Finacom WHEREAS, the proposed landmarking of 2525 Telegraph Avenue, the Needham/Obata Building, was initiated by the Landmarks Preservation Commission at its meeting on February 5, 2009; and WHEREAS, the proposed landmarking of the Needham/Obata Building is exempt from CEQA pursuant to Section 15061.b.3 (activities that can be seen with certainty to have no significant effect on the environment) of the CEQA Guidelines; and WHEREAS, the Landmarks Preservation Commission opened a public hearing on said proposed landmarking on April 2, 2009, and continued the hearing to May 7, 2009, and then to June 4, 2009; and WHEREAS, during the overall public hearing the Landmarks Preservation Commission took public testimony on the proposed landmarking; and WHEREAS, on June 4, 2009, the Landmarks Preservation Commission determined that the subject property is worthy of Landmark status; and WHEREAS, on July 9, 2009, following release of the Notice of Decision (NOD) on June 29, 2009, the property owner Ali Elsami submitted an appeal requesting that the City Council overturn or remand the Landmark decision; and WHEREAS, on September 22, 2009, the City Council considered Staff’s -

Executive Order 9066: a Tragedy of Democracy

Presidential power, government accountability and the challenges of an informed—or uninformed—electorate Volume XVI, No. 2 David Gray Adler The Newsletter of the Idaho Humanities Council Summer 2012 Andrus Center for Public Policy Boise State University “Public discussion is political duty.” Executive Order 9066: A –Justice Louis Brandeis Tragedy of Democracy An Interview with Artist Roger Shimomura President Lyndon Johnson used his power to push through a tremendous agenda of Great Society legislation between 1963 and 1968. Photo Credit: Historical photos for this article provided by the National Park Service The Minidoka Relocation Center, near Jerome, Idaho, became Idaho’s seventh largest city between 1942 and 1945, when nearly yndon Johnson had barely assumed the American 10,000 Japanese Americans from the West Coast were interned during World War II. LPresidency when southern Senators, familiar with the By Russell M. Tremayne Texan’s vaulting ambition, counseled patience and warned him not to try to accomplish too much, too soon. Above all, College of Southern Idaho they sought to warn him away from the temptation to exploit Editor’s Note: In June of 2012, College of Southern most historians agree. Internment is so recent and the his presidential honeymoon–undoubtedly lengthened by the Idaho History Professor Russ Tremayne, along with the issues are so relevant to our time that it is vital to revisit national sorrow that stemmed from the assassination of President Friends of Minidoka and the National Park Service, the events that led to what Dr. Tetsuden Kashima called John F. Kennedy–to push the big ideas, big policies and big pro- planned the 7th annual Civil Liberties Symposium—this “Judgment Without Trial.” grams that had animated his politics as Senate Majority Leader. -

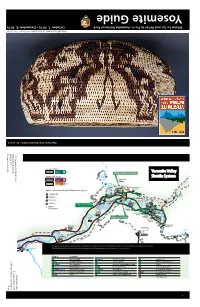

Yosemite Guide Yosemite

Yosemite Guide Yosemite Where to Go and What to Do in Yosemite National Park October 7, 2015 - December 8, 2015 8, December - 2015 7, October Park National Yosemite in Do to What and Go to Where Butterfly basket made by Julia Parker. Parker. Julia by made basket Butterfly NPS Photo / YOSE 50160 YOSE / Photo NPS Volume 40, Issue 8 Issue 40, Volume America Your Experience Yosemite, CA 95389 Yosemite, 577 PO Box Service Park National US DepartmentInterior of the Year-round Route: Valley Yosemite Valley Shuttle Valley Visitor Center Upper Summer-only Routes: Yosemite Shuttle System El Capitan Fall Yosemite Shuttle Village Express Lower Shuttle Yosemite The Ansel Fall Adams l Medical Church Bowl i Gallery ra Clinic Picnic Area l T al Yosemite Area Regional Transportation System F e E1 5 P2 t i 4 m e 9 Campground os Mirror r Y 3 Uppe 6 10 2 Lake Parking Village Day-use Parking seasonal The Ahwahnee Half Dome Picnic Area 11 P1 1 8836 ft North 2693 m Camp 4 Yosemite E2 Housekeeping Pines Restroom 8 Lodge Lower 7 Chapel Camp Lodge Day-use Parking Pines Walk-In (Open May 22, 2015) Campground LeConte 18 Memorial 12 21 19 Lodge 17 13a 20 14 Swinging Campground Bridge Recreation 13b Reservations Rentals Curry 15 Village Upper Sentinel Village Day-use Parking Pines Beach E7 il Trailhead a r r T te Parking e n il i w M in r u d 16 o e Nature Center El Capitan F s lo c at Happy Isles Picnic Area Glacier Point E3 no shuttle service closed in winter Vernal 72I4 ft Fall 2I99 m l E4 Mist Trai Cathedral ail Tr op h Beach Lo or M ey ses erce all only d R V iver E6 Nevada To & Fall The Valley Visitor Shuttle operates from 7 am to 10 pm and serves stops in numerical order. -

Executive Order 9066 and the Residents of Santa Cruz County

Executive Order 9066 and the Residents of Santa Cruz County By Rechs Ann Pedersen Japanese American Citizens League Float, Watsonville Fourth of July Parade, 1941 Photo Courtesy of Bill Tao Copyright 2001 Santa Cruz Public Libraries. The content of this article is the responsibility of the individual author. It is the library’s intent to provide accurate information, however, it is not possible for the library to completely verify the accuracy of all information. If you believe that factual statements in a local history article are incorrect and can provide documentation, please contact the library. 1 Table of Contents Introduction Bibliography Chronology Part 1: The attack on Pearl Harbor up to the signing of Executive Order 9066 (December 7, 1941 to February 18, 1942) Part 2: The signing of Executive Order 9066 to the move to Poston (February 19, 1942 to June 17, 1942) Part 3: During the internment (July 17, 1942 to December 24, 1942) Part 4: During the internment (1943) Part 5: During the internment (1944) Part 6: The release and the return of the evacuees (January 1945 through 1946) Citizenship and Loyalty Alien Land Laws Executive Order 9066: Authorizing the Secretary of War to Prescribe Military Areas Fear of Attack, Fear of Sabotage, Arrests Restrictions on Axis Aliens Evacuation: The Restricted Area Public Proclamation No. 1 Public Proclamation No. 4 Salinas Assembly Center and Poston Relocation Center Agricultural Labor Shortage Military Service Lifting of Restrictions on Italians and Germans Release of the Evacuees Debate over the Return of Persons of Japanese Ancestry Return of the Evacuees 2 Introduction "...the successful prosecution of the war requires every possible protection against espionage and against sabotage." (Executive Order 9066) "This is no time for expansive discourses on protection of civil liberties for Japanese residents of the Pacific coast, whether they be American citizens or aliens." Editorial. -

A Cultural History of Japanese American Internment Camps in Arkansas 1942-1945

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University Communication Theses Department of Communication 11-27-2007 Strangers in their Own Land: A Cultural History of Japanese American Internment Camps in Arkansas 1942-1945 Dori Felice Moss Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/communication_theses Part of the Communication Commons Recommended Citation Moss, Dori Felice, "Strangers in their Own Land: A Cultural History of Japanese American Internment Camps in Arkansas 1942-1945." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2007. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/communication_theses/32 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Communication at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Communication Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STRANGERS IN THEIR OWN LAND: A CULTURAL HISTORY OF JAPANESE AMERICAN INTERNMENT CAMPS IN ARKANSAS 1942-1945 by Dori Moss Under the Direction of Mary Stuckey ABSTRACT While considerable literature on wartime Japanese American internment exists, the vast majority of studies focus on the West Coast experience. With a high volume of literature devoted to this region, lesser known camps in Arkansas, like Rohwer (Desha County) and Jerome (Chicot and Drew County) have been largely overlooked. This study uses a cultural history approach to elucidate the Arkansas internment experience by way of local and camp press coverage. As one of the most segregated and impoverished states during the 1940s, Arkansas‟ two camps were distinctly different from the nine other internment camps used for relocation. Through analysis of local newspapers, Japanese American authored camp newspapers, documentaries, personal accounts and books, this study seeks to expose the seemingly forgotten story of internment in the South. -

Winter 2004 ACLU News

AMERICAN CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION OF NORTHERN CALIFORNIA WINTER 2004 BECAUSE FREEDOM CAN’T PROTECT ITSELF VOLUME LXVIII ISSUE 1 WHAT’S INSIDE news ACLUPAGE 3 PAGE 7 PAGE 8 PAGE 9 CENTER SPREAD PAGE 12 Landmark Settlement Marriages Shut Down: Reforming the SFPD: Backlash Profile: Taking Back the Nation: ACLU Forum: for LGBTI Students ACLU Files Suit SF’s Proposition H What’s in a Name? 2003 Year in Review Saving Choice, Saving Lives HISTORY IN THE MAKING: SAME-SEX COUPLES WED AT CITY HALL hey stepped out of San Francisco’s City Hall and into the history books. Thousands of same-sex couples braved wind, rain, and the wrath of the Tanti-gay lobby this February, waiting hours for a simple privilege that had been denied them for years: a marriage license. GIGI PANDIAN Couples line up outside City Hall, Feb. 17, 2004 “We’ve waited 51 long years for this day, for the right to Newsom explained that he had taken an oath to uphold that first day. get married,” said Del Martin, 83, and Phyllis Lyon, 79, the the California constitution, including its promise of equal Lyon and Martin met in Seattle in 1950, moved to San first couple to wed at City Hall on Feb. 12, 2004. “We’ve protection for all Californians. “What we were doing before Francisco, and bought a house together in 1955. Lyon been in a committed and loving relationship since 1953.” last Thursday [Feb. 12], from my perspective, was clearly, by worked as a journalist; Martin as a bookkeeper, and together Martin and Lyon were one of more than 3,000 gay and any objective, discriminatory,” he told CNN. -

Executive Order 9066 Termination” of the William J

The original documents are located in Box 34, folder “Executive Order 9066 Termination” of the William J. Baroody Files at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Copyright Notice The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Gerald R. Ford donated to the United States of America his copyrights in all of his unpublished writings in National Archives collections. Works prepared by U.S. Government employees as part of their official duties are in the public domain. The copyrights to materials written by other individuals or organizations are presumed to remain with them. If you think any of the information displayed in the PDF is subject to a valid copyright claim, please contact the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Digitized from Box 34 of the William J. Baroody Files at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library An American Promise By the President of the United States of America A Proclamation In this Bicentennial Year, we are commemorating the anniversary dates of many of the great events in American history. An honest reckoning, however, must include a recognition of our national mistakes as well as our national achievements. Learning from our mistakes is not pleasant, but as a great philosopher once admonished, we must do so if we want to avoid repeating them. February 19th is the anniversary of a sad day in American history. It was on that date in 1942, in the midst of the response to the hostilities that began on December 7, 1941, that Executive Order No. -

Chiura Obata (1885-1975)

Chiura Obata (1885-1975) Teacher Packet ©️2020 1 Table of Contents Biography - Chuira Obata 3 Lesson 1 : Obata Inspired Landscape Art (grades K -12) 3 Lesson 2 : Obata-Inspired Poetry (grades 2 - 7) 7 Lesson 3 : Environmentalism “Can Art Save the World?” (grades 4-8) 10 Lesson 4 : 1906 San Francisco Earthquake (grades 4 and above) 13 Lesson 5 : Japanese Incarceration Experience and Political Art (grades 6-12) 18 Resources 22 2 Biography - Chuira Obata Chiura Obata (1885-1975) was a renowned landscape artist, professor, and devoted environmentalist. Born 1885, in Japan, Obata studied ink painting before immigrating to California in 1903. After settling in Japantown in San Francisco, Obata established himself as an artist and took on large-scale commissioned art projects. After an influential trip to Yosemite in 1928, Obata began devoting his art to portraying landscapes and the beauty of nature. Throughout the next decade, Obata continued to earn recognition, but like many Japanese Americans during WWII, his life was violently uprooted as his family was interned, first at Tanforan and then at Topaz. During his imprisonment, Obata was able to start art schools at both camps, teaching hundreds of students and even holding an exhibition in 1942. After the end of the war, Obata returned to lecture at UC Berkeley, joined the Sierra Club’s environmentalist efforts, and consistently celebrated Japanese aesthetics until his death. Over the course of a seven-decade career, Obata became a prominent educator at UC Berkeley and a central leader in -

Obata As an Artist and a Lover of Nature

er 1993 me 55 ber 3 0 mal for bers of the YoseANte mite Association Janice T. Driesbach pact on Obata as an artist and a lover of nature. Chiura Obata B (1885-1975), a In Obata's words, that 1927 Japanese-born artist who spent Yosemite trip "was the greatest most of his adult life in the harvest for my whole life and San Francisco Bay Area, is future in painting. The expres- little-known for his Yosemite- sion from Great Nature is im- inspired work. But Obata, who measurable"' The classically- immigrated to California in trained sumi artist appears to 1903, produced a number of have arrived in the Sierra with A remarkable paintings, sketches a mission; he was determined and woodblock prints of the to record the wondrous land- Yosemite region from the time scapes of Tuolumne Meadows, of his first visit to the park in Mount Lyell, Mono Lake, and 1927 through the rest of his life. the rest of Yosemite's high That initial visit, which lasted country in pencil, sumi, and six weeks, had a profound im- watercolor. The sculptor T FACE. TWO Cover: Allorrriug at Mono Lake, 19 Color woodblock print, 11 x 151' Buck Meadow, June 17, 1927. Su on postcard, 3Y x 5% in. How Old Is the Moon, July 2, 19 Sumi on postcard, 5'U x 3'S in. Robert Boardman Howard, this abundant, great nature, t who accompanied Obata leave here would mean losin during a portion of the trip, great opportunity that come observed, "Every pause for only once in a thousand year rest saw Chiura at work.