The Princess and the Frog

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Metro Response to Public Comments Proposed License for Grimm's Fuel

Metro response to public comments Proposed license for Grimm’s Fuel Company Metro response to public comments received during the comment period in October through November 2018 regarding proposed license conditions for Grimm’s Fuel Company. Prepared by Hila Ritter January 4, 2019 BACKGROUND Grimm’s Fuel Company (Grimm’s), is a locally-owned and operated Metro-licensed yard debris composting facility that primarily accepts yard debris for composting. In general, Metro’s licensing requirements for a composting facility set conditions for receiving, managing, and transferring yard debris and other waste at the facility. The Oregon Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) also has distinct yet complementary requirements for composting facilities and monitors environmental impacts of facilities to protect air, soil, and water quality. Metro and DEQ work closely together to provide regulatory oversight of solid waste facilities such as Grimm’s. On October 22, 2018, Metro opened a formal public comment period for several new conditions of the draft license for Grimm’s. The public comment period closed on November 30, 2018. Metro also hosted a community conversation during that time to further solicit input and discuss next steps. During the formal comment period, Metro received 119 written comments from individuals and businesses (attached). Metro received an additional six written comments via email after the comment period closed at 5 p.m. on November 30, which did not become an official part of the record. After the comment period closed, members of the Tualatin community requested that Metro extend the term of Grimm’s current license for an additional two months to allow the public an opportunity to review the new proposed license in its entirety before it is issued. -

Summer Reading 2021 6

Summer Reading Grade 6 The purpose of the summer reading program is to encourage the enjoyment of reading and the development of independent reading skills. Summer is a time of fun, exploration and growth; it is a perfect time to read. It is our hope at St. Michael School that each of you will become lifelong readers. Students entering sixth grade are required to read two books during the summer. However, it is our hope you will read more than two. One of the books should be chosen from the Summer Reading Book List. 1. Required :Amal Unbound by Aisha Seed. Complete questions on the following page. 2. Free Choice. Choose one book from the Suggested Titles attached. Complete the corresponding assignment. Several of the books on the Reading List are some of the students’ favorites. Feel free to read more than one from the list. The reading and corresponding assignments will be collected on the first day of school. If you have questions or have other book ideas you may message me on Google Classroom Summer Reading, password: etsgxuf. Common Sense Media is an excellent resource to help you understand the nature of the content in the novels: commonsensemedia.org. Enjoy your time reading this summer! Grade 6 Summer Reading List Tuck Everlasting by Natalie Babbitt-Winnie Foster discovers a spring on her family’s property that grants immortality, and she meets members of the Tuck family who have drunk from the stream. Winnie must decide whether she, herself, wants immortality. The Phantom Tollbooth by Norton Juster, Jules Feiffer (illus.)- This ingenious fantasy centers around Milo, a bored ten-year old who comes home to find a large toy tollbooth sitting in his room. -

Download Season 5 Grimm Free Watch Grimm Season 5 Episode 1 Online

download season 5 grimm free Watch Grimm Season 5 Episode 1 Online. On Grimm Season 5 Episode 1, Nick struggles with how to move forward after the beheading of his mother, the death of Juliette and Adalind being pregnant. Watch Similar Shows FREE Amazon Watch Now iTunes Watch Now Vudu Watch Now YouTube Purchase Watch Now Google Play Watch Now NBC Watch Now Verizon On Demand Watch Now. When you watch Grimm Season 5 Episode 1 online, the action picks up right where the season finale of Grimm Season 4 left off, with Juliette dead in Nick's arms, Nick's mother's severed head in a box, and Agent Chavez's goons coming to kidnap Trubel. Nick is apparently drugged, and when he awakes, there is no sign that any of this occurred: no body, no box, no head, no Trubel. Was it all a truly horrible dream? Or part of a larger conspiracy? When he tries to tell his friends what happened, they hesitate to believe his claims, especially when he lays the blame at the feet of Agent Chavez. As his mental state deteriorates, will Nick be able to discover the truth about what happened and why? Where is Trubel now, and why did Chavez and her people come to kidnap her? Will his friends ever believe him, or will they continue to doubt his claims about what happened? And what will Nick do now that his and Adalind's baby is on the way? Tune in and watch Grimm Season 5 Episode 1, "The Grimm Identity," online right here at TV Fanatic to find out what happens. -

PRINCESS Books 11/2018

PRINCESS Books 11/2018 PICTURE BOOKS: Princess Palooza jj Allen, J The Very Fairy Princess jj Andrews, J The Very Fairy Princess: Here Comes the Flower Girl! Jj Andrews, J The Very Fairy Princess Takes the Stage jj Andrews, J The Princess and the Pizza jj Auch, M Snoring Beauty jj Bardhan-Quallen, S The Princess and the Pony jj Beaton, K Marisol McDonald Doesn’t Match = Marisol McDonald No Combina jj Brown, Monica Babar and Zephir jj Brunhoff, J Princess Peepers Picks a Pet jj Calvert, P Puss in Boots jj Cauley, L The Frog Princess jj Cecil, L The Princess and the Pea in Miniature: After the Fairy Tale by Hans Christian Andersen jj Child, L Princess Smartypants jj Cole, B Do Princesses Scrape Their Knees? Jj Coyle, C A Hero’s Quest jj DiCamillo, K The Mouse and the Princess jj DiCamillo, K A Friend for Merida jj Disney The Prince Won’t Go to Bed! Jj Dodds, D A Gold Star for Zog jj Donaldson, J Zog and the Flying Doctors jj Donaldson, J Dora Saves the Snow Princess jj Dora How to Become a Perfect Princess In Five Days jj Dube, P Olivia and the Fairy Princesses jj Falconer, I Olivia: The Princess jj Falconer, I The Most Wonderful Thing in the World jj French, V The Princess Knight jj Funke, C The Snow Rabbit jj Garoche, C Spells jj Gravett, E Fitchburg Public Library 610 Main St, Fitchburg, MA 01420 978-829-1789 www.fitchburgpubliclibrary.org Princesses Save the World jj Guthrie, S Princesses Wear Pants jj Guthrie, S Snoring Beauty jj Hale, B Princess Academy jj Hale, S PA1 Princess Hyacinth: (The Surprising Tale of a Girl Who Floated) -

Copyright and Use of This Thesis This Thesis Must Be Used in Accordance with the Provisions of the Copyright Act 1968

COPYRIGHT AND USE OF THIS THESIS This thesis must be used in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. Reproduction of material protected by copyright may be an infringement of copyright and copyright owners may be entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. Section 51 (2) of the Copyright Act permits an authorized officer of a university library or archives to provide a copy (by communication or otherwise) of an unpublished thesis kept in the library or archives, to a person who satisfies the authorized officer that he or she requires the reproduction for the purposes of research or study. The Copyright Act grants the creator of a work a number of moral rights, specifically the right of attribution, the right against false attribution and the right of integrity. You may infringe the author’s moral rights if you: - fail to acknowledge the author of this thesis if you quote sections from the work - attribute this thesis to another author - subject this thesis to derogatory treatment which may prejudice the author’s reputation For further information contact the University’s Copyright Service. sydney.edu.au/copyright PROFESSIONAL EYES: FEMINIST CRIME FICTION BY FORMER CRIMINAL JUSTICE PROFESSIONALS by Lili Pâquet A thesis submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences University of Sydney 2015 DECLARATION OF ORIGINALITY I hereby certify that this thesis is entirely my own work and that any material written by others has been acknowledged in the text. The thesis has not been presented for a degree or for any other purposes at The University of Sydney or at any other university of institution. -

The Frog Prince, Part I

TThehe FFrogrog PPrince,rince, PPartart I 4 Lesson Objectives Core Content Objectives Students will: Demonstrate familiarity with the fairy tale “The Frog Prince” Identify the fairy tale elements of “The Frog Prince” Identify fairy tales as a type of f ction Identify common characteristics of fairy tales, such as “once upon a time” beginnings, royal characters, elements of fantasy, problems and solutions, and happy endings Language Arts Objectives The following language arts objectives are addressed in this lesson. Objectives aligning with the Common Core State Standards are noted with the corresponding standard in parentheses. Refer to the Alignment Chart for additional standards addressed in all lessons in this domain. Students will: Describe how the princess feels when her golden toy falls into a well, and how the frog feels when the princess lets him into the castle, using words and phrases that suggest feelings (RL.1.4) Describe the princess, the frog, and the king with relevant details, expressing their ideas and feelings clearly (SL.1.4) Prior to listening to “The Frog Prince, Part I,” identify orally what they know and have learned about fairy tales and how princes are depicted in fairy tales Prior to listening to “The Frog Prince, Part I,” orally predict whether the title character is more like a frog or more like the princes they have heard about in other fairy tales and then compare the actual outcome to the prediction 54 Fairy Tales 4 | The Frog Prince, Part I © 2013 Core Knowledge Foundation Perform an aspect of a character from “The Frog Prince, Part I,” for an audience using eye contact, appropriate volume, and clear enunciation Core Vocabulary court, n. -

The Frog Prince Retellings

THIS LIST WILL BE PERIODICALLY UPDATED, as authors come out with new tales and/or as I discover others. Most of the links lead to the Kindle versions of the books. Ratings: These are reading GUIDELINES. Reading ages and abilities vary widely, so please keep in mind that I don’t even pretend to know what you or your kids/siblings/whoever can handle. These ratings are determined based on general reading levels and general content tolerance levels. The rating means a book has one or more of that kind of content, not necessarily all of them. Not every book rated PG-13 is going to have swearing, for example. Sometimes it’s rated that for violence. PG-13 does not necessarily mean ‘clean’. That’s why I’ve added clean to the series that qualify. G: as safe as a kids’ book or family documentary PG: mild violence, mild clean/sweet romance handled lightly, and/or exciting adventures that aren’t too tense. PG-13: some violence, mild physicality and sexuality, and/or mild swearing. PG-16: high levels of violence, psychologically medium-dark scenes, and/or mid-level sexual content, adult concepts, and/or medium-level swear words and frequency. Mature: intense violence, high level sexual content, intense ‘dark’ content, psychologically dark scenes or concepts, and/or lots of swearing. Clean: little to no mild swearing, violence that isn’t graphic, kissing and sexual content handled the same way you’d find in a Hallmark movie. Genre definitions: high fantasy: takes place in a secondary world that has no knowledge of Earth, contains magic/fantasy races/fantasy -

The Brothers Grimm Stories

The Brothers Grimm 항햗햔햙햍햊햗햘 핲햗햎햒햒 1 The Brothers Grimm Letter from the Chair: Dear Delegates, My name is John Ruela and I will be your Chair for the Brothers Grimm Crisis Committee at SHUMUN XXI. I am currently a sophomore majoring in History with minors in Arabic, Middle Eastern Studies and Religious Studies. Although I am personally most interested in the Middle East, I have a love for oral tradition that carried stories to become famous over centuries, and because of this the Brothers Grimm anthology is extremely interesting to me. In my free time, you can find me reading sci-fi, forfeiting sleep to watch bad Netflix shows, and talking too much about world news. Although I had a brief one year experience with Model Congress in high school, I started doing Model UN in my freshman year when I joined Seton Hall’s competitive Model UN team. I co-chaired in SHUMUN XX last year for the Napoleon’s 100 Days Crisis Committee. That was a blast and I cannot wait to experience chairing a fantasy committee this year! With a wide range of local legends and fables, we hope to see the sort of creativity that originally inspired these stories. During the conference I hope to see you excel in your debate and writing skills! I cannot wait to see you all. If you have any questions or concerns about SHUMUN XXI or the Brothers Grimm Crisis Committee, please feel free to email! Best Wishes, John Ruela Brothers Grimm Crisis Committee Chair SHUMUN XXI [email protected] 2 The Brothers Grimm Letter from the Crisis Director: Dear Delegates, Welcome to SHUMUN XXI! My name is Sebastian Kopec, and I have the pleasure of being your Crisis Director for the Brothers Grimm Crisis Committee. -

Reading Patch Club Fairy Tales Book List

Reading Patch Club Fairy Tales Book List Read 20 books for this patch. All books must come from this list. PICTURE BOOKS: These books are shelved by author’s last name unless noted. Extra! Extra! Fairy Tale News Arthur’s Tractor: A Fairy Tale from Hidden Forest with Mechanical Parts Ada, Alma Flor Goodhart, Pippa The Very Fairy Princess The Very Smart Pea and the Andrews, Julie Princess-to-be Grey, Mini The Princesses Have a Ball Bateman, Teresa Who is It? Grindley, Sally The Red Shoes Bazilian, Barbara Fairytale News Hawkins, Colin Puss in Boots Cech, John The Gold Miner’s Daughter: A Melodramatic Fairy Tale Beware of the Storybook Wolves Hopkins, Jackie Child, Lauren Joe Bright and the Seven Genre Dudes Fairly Fairy Tales Hopkins, Jackie Mims Codell, Esmé Raji Once Upon a Bathtime The Duchess of Whimsy: Hughes, Vi An Absolutely Delicious Fairy Tale De Sève, Randall Rapunzel Isadora, Rachel The Princess and the Frog (or any other Disney fairy tale) The Pied Piper’s Magic DISNEY (Marsoli, Lisa Ann) Kellogg, Steven Dinorella: A Prehistoric Fairy Tale Waynetta and the Cornstalk: Edwards, Pamela Duncan A Texas Fairy Tale Ketteman, Helen Princess Pigtoria and the Pea Edwards, Pamela Duncan An Undone Fairy Tale Lendler, Ian Fairy Trails: A Story Told in English and Spanish Sylvia Long’s Thumbelina Elya, Susan Middleton Long, Sylvia Singing to the Sun: A Fairy Tale A Fairy-Tail Adventure French, Vivian Man-Kong, Mary The Squirrel Wife: An Original Kiss Me! (I’m a Prince!) Fairy Tale McLeod, Heather Pearce, Philippa The Dog Prince: An Original Fairy Tale Cinderella, or, The Little Glass Slipper Mills, Lauren A Perrault, Charles Cinder-Elly Snow White Minters, Frances (or other Roberto Piumini fairy tale) Piumini, Roberto Dragon Pizzeria Morgan, Mary The Boy Who Thought He Was a Teddy Bear: A Fairy Tale How Prudence Proovit Proved the Truth Willis, Jeanne About Fairy Tales Paratore, Coleen EARLY READERS: These books are shelved by author’s last name unless noted. -

Fractured Fairy Tales Are Modern Ada, Alma Flor

Mann, Pamela. The Frog Princess. (Frog Scieszka, Jon. True Story of the 3 Little Pigs. Prince) (Three Pigs) McKinley, Robin. Beauty. (Beauty and the The Time Warp Trio Series. (Various) Fractured Beast) The Frog Prince, Continued. (Frog Meddaugh, Susan. Hog-Eye. (Three Pigs) Prince) Sneaker. (Cinderella) The Book That Jack Wrote. (House That McNaughton, Colin. Oops! Jack Built) Fairy Tales Minters, Frances. Cinder-Elly. (Cinderella) The Stinky Cheese Man and Other Fairly Sleepless Beauty. Stupid Tales. (Sleeping Beauty) Silverstein, Shel. In Search of Cinderella. (A Mori, Tuyosi. Socrates and the Three Little Light in the Attic. (Cinderella) Pigs. (Three Pigs) Stanley, Diane. Rumpelstiltskin's Daughter. Munsch, Robert. The Paper Bag Princess. (Rumpelstiltskin) Myers, Bernice. Sidney Rella and the Glass Strauss, Gwen. Trail of Stones (Various) Sneaker. (Cinderella) Tolhurst, Marilyn. Somebody and the Three Napoli, Donna Jo. The Magic Circle. Blairs. (Three Bears) (Hansel and Gretel) Trivizas, Eugenios. The Three Little Wolves The Prince of the Pond. (Frog Prince) and the Big Bad Pig. (Three Pigs) Zel. (Rapunzel) Tunnell, Michael O. Beauty and the Beastly Oppenheim, Joanne. "Not Now!" Said the Cow. Children. (Beauty and the Beast) (Little Red Hen) Turkle, Brinton. Deep in the Forest. (Three Orgel, Doris. Button Soup. (Stone Soup) Bears) Otfinoski, Steven. The Truth About Three Billy Vozar, David. Yo, Hungry Wolf. (Various) Goats Gruff. (Billy Goats Gruff) M.C. Turtle and the Hip Hop Hare. Perlman, Janet. Cinderella Penguin or the Little (Tortoise and the Hare) Glass Flipper.(Cinderella) Wegman, William. Cinderella. (Cinderella) Perlman, Janet. The Emperor Penguin's New Wildsmith, Brian. Jack and the Meanstalk. -

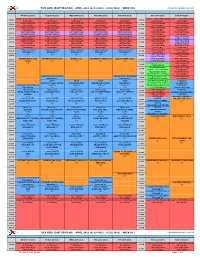

TLEX GRID (EAST REGULAR) - APRIL 2021 (4/12/2021 - 4/18/2021) - WEEK #16 Date Updated:3/25/2021 2:29:43 PM

TLEX GRID (EAST REGULAR) - APRIL 2021 (4/12/2021 - 4/18/2021) - WEEK #16 Date Updated:3/25/2021 2:29:43 PM MON (4/12/2021) TUE (4/13/2021) WED (4/14/2021) THU (4/15/2021) FRI (4/16/2021) SAT (4/17/2021) SUN (4/18/2021) SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM 05:00A 05:00A NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 05:30A 05:30A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 06:00A 06:00A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 06:30A 06:30A (SUBNETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 07:00A 07:00A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 07:30A 07:30A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 08:00A 08:00A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) CASO CERRADO CASO CERRADO CASO CERRADO -

Gas Tax up for Renewal Today County Sets June 5 Date for Public Hearing

SPORTS LOCAL Red & Black game Crash sends 1 ends in tie, 1B. to hospital, 3A. JASON MATTHEW WALKER/Lake City Reporter PATRICK SCOTT/Special to the Reporter WEEKEND EDITION FRIDAY & SATURDAY, MAY 16-17, 2014 | YOUR COMMUNITY NEWSPAPER SINCE 1874 | 75¢ Lake City Reporter LAKECITYREPORTER.COM Gas tax up for renewal Today County sets June 5 date for public hearing. Revenues from the tax have cally the county would scale back Antique Bottle show gone toward local road improve- the lost revenue amounts in those The Florida Antique By TONY BRITT a four cent local option fuel tax ments and transportation proj- projects,” County Manager Dale Bottle Collectors Show will [email protected] that has been in effect more than ects. Williams said after the meeting. be at the Columbia County 25 years. The hearing date was “We use the proceeds from the The tax will lapse Dec. 31 unless Fairground May 16 from The county commission will chosen at Thursday’s county com- tax to fund transportation projects 4-7 p.m. and May 17 from 8 decide June 5 whether to renew mission meeting. and if it’s not renewed then basi- GAS TAX continued on 3A a.m. to 3 p.m. Early buyers admission is $20; general admission is $3. There are still tables available at a cost of $35 each. A portion of the proceeds will go to Fellowship Church in High Springs. Call 386-804-9635 Tornado touches down with questions. Farmers Market No injuries in small twister. The Live Oak farm- ers market is now open By MEGAN REEVES Fridays from 12-6 p.m.