NOAA Technical Report NMFS SSRF-691

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Redalyc.A Review of the Flatfish Fisheries of the South Atlantic Ocean

Revista de Biología Marina y Oceanografía ISSN: 0717-3326 [email protected] Universidad de Valparaíso Chile Díaz de Astarloa, Juan M. A review of the flatfish fisheries of the south Atlantic Ocean Revista de Biología Marina y Oceanografía, vol. 37, núm. 2, diciembre, 2002, pp. 113-125 Universidad de Valparaíso Viña del Mar, Chile Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=47937201 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative Revista de Biología Marina y Oceanografía 37 (2): 113 - 125, diciembre de 2002 A review of the flatfish fisheries of the south Atlantic Ocean Una revisión de las pesquerías de lenguados del Océano Atlántico sur Juan M. Díaz de Astarloa1 2 1CONICET, Departamento de Ciencias Marinas, Facultad de Ciencias Exactas y Naturales, Universidad Nacional de Mar del Plata, Funes 3350, 7600 Mar del Plata, Argentina. [email protected] 2 Current address: Laboratory of Marine Stock-enhancement Biology, Division of Applied Biosciences, Graduate School of Agriculture, Kyoto University, kitashirakawa-oiwakecho, sakyo-ku, Kyoto, 606-8502 Japan. [email protected] Resumen.- Se describen las pesquerías de lenguados del Abstract.- The flatfish fisheries of the South Atlantic Atlántico sur sobre la base de series de valores temporales de Ocean are described from time series of landings between desembarcos pesqueros entre los años 1950 y 1998, e 1950 and 1998 and available information on species life información disponible sobre características biológicas, flotas, history, fleets and gear characteristics, and economical artes de pesca e importancia económica de las especies importance of commercial species. -

FISH LIST WISH LIST: a Case for Updating the Canadian Government’S Guidance for Common Names on Seafood

FISH LIST WISH LIST: A case for updating the Canadian government’s guidance for common names on seafood Authors: Christina Callegari, Scott Wallace, Sarah Foster and Liane Arness ISBN: 978-1-988424-60-6 © SeaChoice November 2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS GLOSSARY . 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY . 4 Findings . 5 Recommendations . 6 INTRODUCTION . 7 APPROACH . 8 Identification of Canadian-caught species . 9 Data processing . 9 REPORT STRUCTURE . 10 SECTION A: COMMON AND OVERLAPPING NAMES . 10 Introduction . 10 Methodology . 10 Results . 11 Snapper/rockfish/Pacific snapper/rosefish/redfish . 12 Sole/flounder . 14 Shrimp/prawn . 15 Shark/dogfish . 15 Why it matters . 15 Recommendations . 16 SECTION B: CANADIAN-CAUGHT SPECIES OF HIGHEST CONCERN . 17 Introduction . 17 Methodology . 18 Results . 20 Commonly mislabelled species . 20 Species with sustainability concerns . 21 Species linked to human health concerns . 23 Species listed under the U .S . Seafood Import Monitoring Program . 25 Combined impact assessment . 26 Why it matters . 28 Recommendations . 28 SECTION C: MISSING SPECIES, MISSING ENGLISH AND FRENCH COMMON NAMES AND GENUS-LEVEL ENTRIES . 31 Introduction . 31 Missing species and outdated scientific names . 31 Scientific names without English or French CFIA common names . 32 Genus-level entries . 33 Why it matters . 34 Recommendations . 34 CONCLUSION . 35 REFERENCES . 36 APPENDIX . 39 Appendix A . 39 Appendix B . 39 FISH LIST WISH LIST: A case for updating the Canadian government’s guidance for common names on seafood 2 GLOSSARY The terms below are defined to aid in comprehension of this report. Common name — Although species are given a standard Scientific name — The taxonomic (Latin) name for a species. common name that is readily used by the scientific In nomenclature, every scientific name consists of two parts, community, industry has adopted other widely used names the genus and the specific epithet, which is used to identify for species sold in the marketplace. -

Pleuronectidae, Poecilopsettidae, Achiridae, Cynoglossidae

1536 Glyptocephalus cynoglossus (Linnaeus, 1758) Pleuronectidae Witch flounder Range: Both sides of North Atlantic Ocean; in the western North Atlantic from Strait of Belle Isle to Cape Hatteras Habitat: Moderately deep water (mostly 45–330 m), deepest in southern part of range; found on mud, muddy sand or clay substrates Spawning: May–Oct in Gulf of Maine; Apr–Oct on Georges Bank; Feb–Jul Meristic Characters in Middle Atlantic Bight Myomeres: 58–60 Vertebrae: 11–12+45–47=56–59 Eggs: – Pelagic, spherical Early eggs similar in size Dorsal fin rays: 97–117 – Diameter: 1.2–1.6 mm to those of Gadus morhua Anal fin rays: 86–102 – Chorion: smooth and Melanogrammus aeglefinus Pectoral fin rays: 9–13 – Yolk: homogeneous Pelvic fin rays: 6/6 – Oil globules: none Caudal fin rays: 20–24 (total) – Perivitelline space: narrow Larvae: – Hatching occurs at 4–6 mm; eyes unpigmented – Body long, thin and transparent; preanus length (<33% TL) shorter than in Hippoglossoides or Hippoglossus – Head length increases from 13% SL at 6 mm to 22% SL at 42 mm – Body depth increases from 9% SL at 6 mm to 30% SL at 42 mm – Preopercle spines: 3–4 occur on posterior edge, 5–6 on lateral ridge at about 16 mm, increase to 17–19 spines – Flexion occurs at 14–20 mm; transformation occurs at 22–35 mm (sometimes delayed to larger sizes) – Sequence of fin ray formation: C, D, A – P2 – P1 – Pigment intensifies with development: 6 bands on body and fins, 3 major, 3 minor (see table below) Glyptocephalus cynoglossus Hippoglossoides platessoides Total myomeres 58–60 44–47 Preanus length <33%TL >35%TL Postanal pigment bars 3 major, 3 minor 3 with light scattering between Finfold pigment Bars extend onto finfold None Flexion size 14–20 mm 9–19 mm Ventral pigment Scattering anterior to anus Line from anus to isthmus Early Juvenile: Occurs in nursery habitats on continental slope E. -

A Practical Handbook for Determining the Ages of Gulf of Mexico And

A Practical Handbook for Determining the Ages of Gulf of Mexico and Atlantic Coast Fishes THIRD EDITION GSMFC No. 300 NOVEMBER 2020 i Gulf States Marine Fisheries Commission Commissioners and Proxies ALABAMA Senator R.L. “Bret” Allain, II Chris Blankenship, Commissioner State Senator District 21 Alabama Department of Conservation Franklin, Louisiana and Natural Resources John Roussel Montgomery, Alabama Zachary, Louisiana Representative Chris Pringle Mobile, Alabama MISSISSIPPI Chris Nelson Joe Spraggins, Executive Director Bon Secour Fisheries, Inc. Mississippi Department of Marine Bon Secour, Alabama Resources Biloxi, Mississippi FLORIDA Read Hendon Eric Sutton, Executive Director USM/Gulf Coast Research Laboratory Florida Fish and Wildlife Ocean Springs, Mississippi Conservation Commission Tallahassee, Florida TEXAS Representative Jay Trumbull Carter Smith, Executive Director Tallahassee, Florida Texas Parks and Wildlife Department Austin, Texas LOUISIANA Doug Boyd Jack Montoucet, Secretary Boerne, Texas Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries Baton Rouge, Louisiana GSMFC Staff ASMFC Staff Mr. David M. Donaldson Mr. Bob Beal Executive Director Executive Director Mr. Steven J. VanderKooy Mr. Jeffrey Kipp IJF Program Coordinator Stock Assessment Scientist Ms. Debora McIntyre Dr. Kristen Anstead IJF Staff Assistant Fisheries Scientist ii A Practical Handbook for Determining the Ages of Gulf of Mexico and Atlantic Coast Fishes Third Edition Edited by Steve VanderKooy Jessica Carroll Scott Elzey Jessica Gilmore Jeffrey Kipp Gulf States Marine Fisheries Commission 2404 Government St Ocean Springs, MS 39564 and Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission 1050 N. Highland Street Suite 200 A-N Arlington, VA 22201 Publication Number 300 November 2020 A publication of the Gulf States Marine Fisheries Commission pursuant to National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Award Number NA15NMF4070076 and NA15NMF4720399. -

CHECKLIST and BIOGEOGRAPHY of FISHES from GUADALUPE ISLAND, WESTERN MEXICO Héctor Reyes-Bonilla, Arturo Ayala-Bocos, Luis E

ReyeS-BONIllA eT Al: CheCklIST AND BIOgeOgRAphy Of fISheS fROm gUADAlUpe ISlAND CalCOfI Rep., Vol. 51, 2010 CHECKLIST AND BIOGEOGRAPHY OF FISHES FROM GUADALUPE ISLAND, WESTERN MEXICO Héctor REyES-BONILLA, Arturo AyALA-BOCOS, LUIS E. Calderon-AGUILERA SAúL GONzáLEz-Romero, ISRAEL SáNCHEz-ALCántara Centro de Investigación Científica y de Educación Superior de Ensenada AND MARIANA Walther MENDOzA Carretera Tijuana - Ensenada # 3918, zona Playitas, C.P. 22860 Universidad Autónoma de Baja California Sur Ensenada, B.C., México Departamento de Biología Marina Tel: +52 646 1750500, ext. 25257; Fax: +52 646 Apartado postal 19-B, CP 23080 [email protected] La Paz, B.C.S., México. Tel: (612) 123-8800, ext. 4160; Fax: (612) 123-8819 NADIA C. Olivares-BAñUELOS [email protected] Reserva de la Biosfera Isla Guadalupe Comisión Nacional de áreas Naturales Protegidas yULIANA R. BEDOLLA-GUzMáN AND Avenida del Puerto 375, local 30 Arturo RAMíREz-VALDEz Fraccionamiento Playas de Ensenada, C.P. 22880 Universidad Autónoma de Baja California Ensenada, B.C., México Facultad de Ciencias Marinas, Instituto de Investigaciones Oceanológicas Universidad Autónoma de Baja California, Carr. Tijuana-Ensenada km. 107, Apartado postal 453, C.P. 22890 Ensenada, B.C., México ABSTRACT recognized the biological and ecological significance of Guadalupe Island, off Baja California, México, is Guadalupe Island, and declared it a Biosphere Reserve an important fishing area which also harbors high (SEMARNAT 2005). marine biodiversity. Based on field data, literature Guadalupe Island is isolated, far away from the main- reviews, and scientific collection records, we pres- land and has limited logistic facilities to conduct scien- ent a comprehensive checklist of the local fish fauna, tific studies. -

Early Stages of Fishes in the Western North Atlantic Ocean Volume

ISBN 0-9689167-4-x Early Stages of Fishes in the Western North Atlantic Ocean (Davis Strait, Southern Greenland and Flemish Cap to Cape Hatteras) Volume One Acipenseriformes through Syngnathiformes Michael P. Fahay ii Early Stages of Fishes in the Western North Atlantic Ocean iii Dedication This monograph is dedicated to those highly skilled larval fish illustrators whose talents and efforts have greatly facilitated the study of fish ontogeny. The works of many of those fine illustrators grace these pages. iv Early Stages of Fishes in the Western North Atlantic Ocean v Preface The contents of this monograph are a revision and update of an earlier atlas describing the eggs and larvae of western Atlantic marine fishes occurring between the Scotian Shelf and Cape Hatteras, North Carolina (Fahay, 1983). The three-fold increase in the total num- ber of species covered in the current compilation is the result of both a larger study area and a recent increase in published ontogenetic studies of fishes by many authors and students of the morphology of early stages of marine fishes. It is a tribute to the efforts of those authors that the ontogeny of greater than 70% of species known from the western North Atlantic Ocean is now well described. Michael Fahay 241 Sabino Road West Bath, Maine 04530 U.S.A. vi Acknowledgements I greatly appreciate the help provided by a number of very knowledgeable friends and colleagues dur- ing the preparation of this monograph. Jon Hare undertook a painstakingly critical review of the entire monograph, corrected omissions, inconsistencies, and errors of fact, and made suggestions which markedly improved its organization and presentation. -

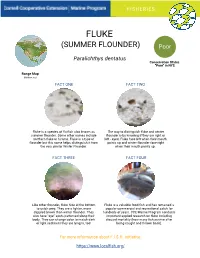

Copy of Summer Flounder/Fluke Fast Facts

YOFUISTH EERDUIECSATION FLUKE (SUMMER FLOUNDER) Poor Paralichthys dentatus Conservation Status "Poor" in NYS Range Map (fishbase.org) FACT ONE FACT TWO Fluke is a species of flatfish also known as The way to distinguish fluke and winter summer flounder. Some other names include flounder is by knowing if they are right or northern fluke or hirame. Fluke is a type of left - eyed. Fluke face left when their mouth flounder but this name helps distinguish it from points up and winter flounder face right the very similar Winter Flounder. when their mouth points up. FACT THREE FACT FOUR Like other flounder, fluke hide at the bottom Fluke is a valuable food fish and has remained a to catch prey. They are a lighter, more popular commercial and recreational catch for dappled brown than winter flounder. They hundreds of years. CCE Marine Program conducts also have “eye” spots patterned along their important applied research on fluke including body. They can change color to match dark discard mortality (how many fish survive after or light sediment they are lying in, too! being caught and thrown back). For more information about F.I.S.H. Initiative: https://www.localfish.org/ FISHERIES Overview Status Fluke are found in inshore and offshore Summer flounder are not overfished and are not waters from Nova Scotia, Canada, to the east subject to overfishing, according to the Atlantic coast of Florida along the East Coast of the States Marine Fisheries Commission (ASMFC). United States. It is a left-eyed flatfish that However, the population of Fluke has decreased over lives 12 to 14 years. -

Ecography ECOG-03961 Flanagan, P

Ecography ECOG-03961 Flanagan, P. H., Jensen, O. P., Morley, J. W. and Pinsky, M. L. 2019. Response of marine communities to local temperature changes. – Ecography doi: 10.1111/ ecog.03961 Supplementary material Appendix 1 2 3 4 5 6 Figure A1. Boxplots of annual survey sampling days per year in spring (a) and fall (b), bottom 7 temperature measurements per year in spring (c) and fall (d), and bottom temperatures per day of 8 year in spring (e) and fall (f) time series. Black bars indicate mean, gray boxes include 95% of 9 range, and whiskers include entire range of data points. 10 1 11 12 Figure A2. Histogram of Species Thermal Index values for the 246 demersal fish and invertebrate 13 species found in the Northeast U.S. Continental Shelf ecosystem and used in this study. 2 14 15 16 Figure A3. Maps of the difference in slopes of long-term trends (bottom temperature slope minus 17 CTI slope) in (a) spring and (b) fall strata. 3 18 19 Figure A4. Model II major axis linear regression between change in temperature-only model CTI 20 and change in observed CTI in spring (a) and fall (b) communities. Spring slope = 0.88, r2 = 21 0.066, P = 0.0223; fall slope = 0.465, r2 = 0.062, P = 0.026. 4 22 23 24 25 Figure A5. Pearson’s correlations between interannual values of bottom temperature or null 26 model CTI and observed CTI in each stratum and season. (a) Histogram of r values between 27 bottom temperature and observed CTI, with dashed line denoting mean (n = 160, mean r = 28 0.381). -

Pleuronectidae

FAMILY Pleuronectidae Rafinesque, 1815 - righteye flounders [=Heterosomes, Pleronetti, Pleuronectia, Diplochiria, Poissons plats, Leptosomata, Diprosopa, Asymmetrici, Platessoideae, Hippoglossoidinae, Psettichthyini, Isopsettini] Notes: Hétérosomes Duméril, 1805:132 [ref. 1151] (family) ? Pleuronectes [latinized to Heterosomi by Jarocki 1822:133, 284 [ref. 4984]; no stem of the type genus, not available, Article 11.7.1.1] Pleronetti Rafinesque, 1810b:14 [ref. 3595] (ordine) ? Pleuronectes [published not in latinized form before 1900; not available, Article 11.7.2] Pleuronectia Rafinesque, 1815:83 [ref. 3584] (family) Pleuronectes [senior objective synonym of Platessoideae Richardson, 1836; family name sometimes seen as Pleuronectiidae] Diplochiria Rafinesque, 1815:83 [ref. 3584] (subfamily) ? Pleuronectes [no stem of the type genus, not available, Article 11.7.1.1] Poissons plats Cuvier, 1816:218 [ref. 993] (family) Pleuronectes [no stem of the type genus, not available, Article 11.7.1.1] Leptosomata Goldfuss, 1820:VIII, 72 [ref. 1829] (family) ? Pleuronectes [no stem of the type genus, not available, Article 11.7.1.1] Diprosopa Latreille, 1825:126 [ref. 31889] (family) Platessa [no stem of the type genus, not available, Article 11.7.1.1] Asymmetrici Minding, 1832:VI, 89 [ref. 3022] (family) ? Pleuronectes [no stem of the type genus, not available, Article 11.7.1.1] Platessoideae Richardson, 1836:255 [ref. 3731] (family) Platessa [junior objective synonym of Pleuronectia Rafinesque, 1815, invalid, Article 61.3.2 Hippoglossoidinae Cooper & Chapleau, 1998:696, 706 [ref. 26711] (subfamily) Hippoglossoides Psettichthyini Cooper & Chapleau, 1998:708 [ref. 26711] (tribe) Psettichthys Isopsettini Cooper & Chapleau, 1998:709 [ref. 26711] (tribe) Isopsetta SUBFAMILY Atheresthinae Vinnikov et al., 2018 - righteye flounders GENUS Atheresthes Jordan & Gilbert, 1880 - righteye flounders [=Atheresthes Jordan [D. -

A Review of Soles of the Genus Aseraggodes from the South Pacific, with Descriptions of Seven New Species and a Diagnosis of Synclidopus

Memoirs of Museum Victoria 62(2): 191–212 (2005) ISSN 1447-2546 (Print) 1447-2554 (On-line) http://www.museum.vic.gov.au/memoirs/index.asp A review of soles of the genus Aseraggodes from the South Pacific, with descriptions of seven new species and a diagnosis of Synclidopus. JOHN E. RANDALL Bishop Museum, 1525 Bernice St. Honolulu, Hawai’i 96817–2704, USA ([email protected]) Abstract Randall, J.E. 2005. A review of soles of the genus Aseraggodes from the South Pacific, with descriptions of seven new species and a diagnosis of Synclidopus. Memoirs of Museum Victoria 62(2): 191–212 The soleid genus Parachirus Matsubara and Ochiai is referred to the synonymy of Aseraggodes Kaup. Aseraggodes persimilis (Günther) and A. ocellatus Weed are reclassified in the genus Pardachirus Günther. Synclidopus macleayanus (Ramsay) from Queensland and NSW is redescribed. A diagnosis is given for Aseraggodes, and a key and species accounts provided for the following 12 species of the genus from islands of Oceania in the South Pacific and the east coast of Australia: A. auroculus, sp. nov. from the Society Islands; A. bahamondei from Easter Island and Lord Howe Island; A. cyclurus, sp. nov. from the Society Islands; A. lateralis, sp. nov. from the Marquesas Islands; A. lenisquamis, sp. nov. from NSW; A. magnoculus sp. nov. from New Caledonia; A. melanostictus (Peters) from 73 m off Bougainville and a first record for the Great Barrier Reef from 115 m; A. nigrocirratus, sp. nov. from NSW; A. normani Chabanaud from southern Queensland and NSW; A. pelvicus, sp. nov. -

An Annotated Bibliography of Diet Studies of Fish of the Southeast United States and Gray’S Reef National Marine Sanctuary

Marine Sanctuaries Conservation Series MSD-05-2 An annotated bibliography of diet studies of fish of the southeast United States and Gray’s Reef National Marine Sanctuary U.S. Department of Commerce February 2005 National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration National Ocean Service Office of Ocean and Coastal Resource Management Marine Sanctuaries Division About the Marine Sanctuaries Conservation Series The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Marine Sanctuary Division (MSD) administers the National Marine Sanctuary Program. Its mission is to identify, designate, protect and manage the ecological, recreational, research, educational, historical, and aesthetic resources and qualities of nationally significant coastal and marine areas. The existing marine sanctuaries differ widely in their natural and historical resources and include nearshore and open ocean areas ranging in size from less than one to over 5,000 square miles. Protected habitats include rocky coasts, kelp forests, coral reefs, sea grass beds, estuarine habitats, hard and soft bottom habitats, segments of whale migration routes, and shipwrecks. Because of considerable differences in settings, resources, and threats, each marine sanctuary has a tailored management plan. Conservation, education, research, monitoring and enforcement programs vary accordingly. The integration of these programs is fundamental to marine protected area management. The Marine Sanctuaries Conservation Series reflects and supports this integration by providing a forum for publication and discussion of the complex issues currently facing the National Marine Sanctuary Program. Topics of published reports vary substantially and may include descriptions of educational programs, discussions on resource management issues, and results of scientific research and monitoring projects. The series facilitates integration of natural sciences, socioeconomic and cultural sciences, education, and policy development to accomplish the diverse needs of NOAA’s resource protection mandate. -

Amendment 1 to the Interstate Fishery Management Plan for Inshore Stocks of Winter Flounder

Fishery Management Report No. 43 of the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission Working towards healthy, self-sustaining populations for all Atlantic coast fish species or successful restoration well in progress by the year 2015. Amendment 1 to the Interstate Fishery Management Plan for Inshore Stocks of Winter Flounder November 2005 Fishery Management Report No. 43 of the ATLANTIC STATES MARINE FISHERIES COMMISSION Amendment 1 to the Interstate Fishery Management Plan for Inshore Stocks of Winter Flounder Approved: February 10, 2005 Amendment 1 to the Interstate Fishery Management Plan for Inshore Stocks of Winter Flounder Prepared by Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission Winter Flounder Plan Development Team Plan Development Team Members: Lydia Munger, Chair (ASMFC), Anne Mooney (NYSDEC), Sally Sherman (ME DMR), and Deb Pacileo (CT DEP). This Management Plan was prepared under the guidance of the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission’s Winter Flounder Management Board, Chaired by David Borden of Rhode Island followed by Pat Augustine of New York. Technical and advisory assistance was provided by the Winter Flounder Technical Committee, the Winter Flounder Stock Assessment Subcommittee, and the Winter Flounder Advisory Panel. This is a report of the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission pursuant to U.S. Department of Commerce, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Award No. NA04NMF4740186. ii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1.0 Introduction The Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission (ASMFC) authorized development of a Fishery Management Plan (FMP) for winter flounder (Pseudopleuronectes americanus) in October 1988. Member states declaring an interest in this species were the states of Maine, New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Connecticut, New York, New Jersey, and Delaware.