Primary Sources and Closure in Showdown! Making Modern Unions Rob Kristofferson and Simon Orpana

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Free a Peoples History of American Empire Pdf

FREE A PEOPLES HISTORY OF AMERICAN EMPIRE PDF Howard Zinn | 288 pages | 30 May 2008 | Henry Holt & Company Inc | 9780805087444 | English | New York, NY, United States A People's History of American Empire: A Graphic Adaptation - Zinn Education Project Uh-oh, it looks like your Internet Explorer is out of date. For a better shopping experience, please upgrade now. Javascript is not enabled in your browser. Enabling JavaScript in your browser will allow you to experience all the features of our site. Learn how to enable JavaScript on your browser. NOOK Book. Questions for Discussion 1. One thing that sets this book apart, particularly as a work in the "graphic novel" genre, is its great variety of visual imagery. We find within these pages various photographs, maps, printed-page excerpts, diagrams, posters and poster-like advertisements, newspaper and magazine clippings, political cartoons, and, of course, many A Peoples History of American Empire both comics-based and realistic. Point out memorable examples of each A Peoples History of American Empire these categories. What is meant in this book by the word "empire"? Discuss this key term with your fellow students. Define "ghost dance. What does he mean when he states on page 17 : "The nation's hoop is broken and scattered"? The phrase A Peoples History of American Empire White Men" appears on more than one occasion A Peoples History of American Empire these pages. When, and in what context, does the phrase first appear? Who does this phrase signify, both specifically and generally? Eugene V. Debs makes his first appearance in this book on page Who was Debs? Why was he both revered and hated? For what is he best known today? And where else do we encounter him in these pages? How does it work? Where has it been utilized, over the years and across the globe? In the bottom panel of page 33, we see a maid or domestic servant waiting on a wealthy white person. -

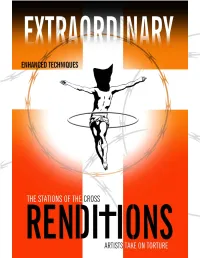

Torture of Detainees, and Summary Executions

Table of Contents 1 Introduction 2 STATION I: Jesus Is Condemned to Death Michael Connors 4 STATION II: Jesus Carries His Cross John Hitchcock 6 STATION III: Jesus Falls the First Time Michael Duffy 8 STATION IV: Jesus Meets His Mother Colm McCarthy 10 STATION V: Simon Helps Jesus Carry His Cross Miguel A. Peña 12 STATION VI: Veronica Wipes the Face of Jesus Mike Konopacki 14 STATION VII: Jesus Falls the Second Time Miguel A. Peña 16 STATION VIII: Jesus Meets the Pious Women of Jerusalem Colm McCarthy 18 STATION IX: Jesus Falls the Third Time Lester Doré 20 STATION X: Jesus Is Stripped of His Garments Steve Chappell 22 STATION XI: Jesus Is Nailed to the Cross Pamela Cremer 24 STATION XII: Jesus Dies on the Cross Mike Konopacki 26 STATION XIII: Jesus Is Taken Down from the Cross Quincy Neri 28 STATION XIV: Jesus Is Laid in the Tomb Lester Doré Extraordinary Renditions ince 9/11, the US empire has been embroiled in a “War on Terror” against Islamic fundamentalism. All sides in this “war” have used religious justification for the most Sheinous of crimes: mass killings of innocent civilians, torture of detainees, and summary executions. Fundamentalists of the three Abrahamic religions — Judaism, Christianity, and Islam — have rejected traditions of peace to wage “jihad” and “just war.” As citizen artists in an empire, we feel compelled to protest our government’s criminality and the failure of major religious, medical, and legal associations to speak out against these atrocities. Decisions to torture detainees to elicit information came directly from George W. -

Here Are Food Shelf Needs Including About 10,000 with This Saturday Is the Letter Carriers Food Drive and Since Some Form of Asbestosis

(ISSN 0023-6667) An Injury to One is an Injury to All! WEDNESDAY VOL. 113 MAY 7, 2008 NO. 21 Huge jump in Latino deaths (Washington, April 28) - - Workplace fatalities have increased sharply for Latino and immigrant workers, reports the new AFL- CIO annual study: Death on the Job: The Toll of Neglect. In 2006, fatal injuries among Latino workers increased by seven percent over 2005, with 990 fatalities among this group of work- ers, the highest number ever reported. The total number of fatal workplace injuries in the United States was 5,840, an increase from the year before. On average, 16 workers were fatally injured and another 11,200 workers were injured or made ill each day in 2006. These statistics do not include deaths from occupational diseases, which claim the lives Fire Fighter Local 101’s Honor Guard was led by Sandy Solem as those who attended of an estimated 50,000 to 60,000 more workers each year. Duluth’s Workers Memorial Day observance April 28 gave their respect. It was the start of The fatality rate among Hispanic workers in 2006 was 25 per- a solemn occasion that remembered ten workers who lost their lives in the last year. cent higher than the fatal injury rate for all U.S. workers. Since 1992, when data was first collected in the BLS Census of Fatal Ten remembered at Workers’ Memorial Occupational Injuries, the number of fatalities among Latino The Twin Port’s observance young to be gone. Their fami- A tree was planted behind workers has increased by 86 percent, from 533 fatal injuries in of Workers’ Memorial Day lies came from Wisconsin and the Duluth Labor Temple to 1992 to 990 deaths in 2006. -

IWW UPS Workers Organize Against Police Brutality by Screw Ups Targets and Holds Hundreds of Contracts Ferry These Packages to Their Intended Starting on Friday, Aug

OFFICIAL NEWSPAPER oF THE INDUSTRIAL WORKERS OF THE WORLD INDUSTRIALOctober 2014 #1768 Vol. 111 No. 7 $2/ £2/ €2 WORKER New Survey Of Online Baltimore Jimmy Review: Wobbly Poet Sharing Lessons IWW Sign-Ups: A Wake- John’s Workers File Keeps Tradition Of With Comrades In Up Call 3 ULP Lawsuit 5 Labor Poetry Alive 8 The FAU 12 IWW UPS Workers Organize Against Police Brutality By Screw Ups targets and holds hundreds of contracts ferry these packages to their intended Starting on Friday, Aug. 22, IWW with police departments, federal agencies, trailers. Those who were uncomfort- workers at a United Parcel Service (UPS) and military branches across the United able or unable to directly engage in sorting facility in Minneapolis began orga- States. The company has held at least 10 these actions posed with a sign reading nizing against their labor supporting the contracts with federal agencies in Mis- “#handsupdontship” in order to speak ongoing police violence against the popu- souri, and far more with county and local out. Actions like this took place in vari- lation of Ferguson, Mo., in the aftermath of police departments and other agencies. ous work areas across the building, and the murder of Michael Brown, an unarmed They sell product lines like “Urban Street were taken by people with a variety of 18-year-old black man. In a series of ac- Violence,” featuring photos of stereotypi- job positions. The following Monday, tions aimed at a local company shipping cal “thugs,” and previously were forced to several workers continued the action, questionable shooting-range targets to law withdraw a line of targets called “No setting more targets aside for the second enforcement agencies nationwide, workers More Hesitation,” featuring pictures of consecutive shift. -

2015 Biennial Conference

2015 Biennial Conference August 20-22 (Pre-conference session August 19) The Madison Concourse Hotel Madison, Wisconsin Dear Sister or Brother: Plans are set for the 2015 biennial conference of the American Postal Workers Union National Postal Press Association (PPA). Included in this booklet is hotel information, condensed schedule of events, workshop descriptions, listing of conference instructors and registration form. Established in 1967, this event is part of the PPA’s mission; helping communicators fulfill their responsibilities of informing and energizing the membership of our great union. The intensive four-day program consists of eleven workshops that will be helpful to all who attend; from novice to experienced, to local or state organizations interested in establishing or enhancing a communications program for its membership. Also featured will be two general sessions, along with four networking events. Faced with a variety of issues affecting our livelihood, these are indeed trying times for postal workers. As a means to confront these challenges, it is especially important to have an active, supportive and united membership. How can this be accomplished? We should consider the value of maintaining a presence with our members and in our communities by the regular use of effective communication mediums; such as newsletters, social media and by communicating through public forums as well. The PPA conference is an opportunity to learn more about communicating – a valuable activity that can influence not only the membership but also everyone the union needs to reach in order to promote and protect the interests of union members and their families. See you in Madison! In solidarity, Tony Carobine President Hotel Information The conference will be held at The Madison Concourse Hotel in Madison, Wisconsin. -

Disciplining Comics

Disciplining Comics: The Transdisciplinary Mellon Workshop at the University of Wisconsin-Madison Adam L. Kern I’m grateful for the opportunity to speak with you today, not on my research field of manga, but on the related field of comics studies. Specifically, I was asked that I share my experiences as the chief architect of a comics studies program at a major U.S. university, with the role of artists in our research and teach- ing. The program, simply called Comics Studies, emanated from a two-long year workshop, or series of talks, conferences, and events, funded by the A.W. Mellon Foundation, and held at the University of Wis- consin-Madison, one of the top ten public universities in the U.S. My four major goals were first to assess the state of the local comics studies community, which is to say, to see if anyone on campus was interest- ed in comics in their teaching or research, second, to gauge interest in building a comics studies program, and third, assuming there was enough interest, to figure out how to build a comics studies program when the field of comics studies is only now beginning to emerge, for there is little agreement on what comics is. How, in other words, can one discipline comics? And fourth, I wanted to figure out how manga would fit into comics studies. As an academic, for me, I always assumed that the key players in building a comics studies pro- gram on campus would be fellow academics—not businessmen, regular joes, former guests on the David Letterman show, or preschool aged kids. -

![Kp3hl [Free Pdf] a People's History of American Empire: the American Empire Project, a Graphic Adaptation Online](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5792/kp3hl-free-pdf-a-peoples-history-of-american-empire-the-american-empire-project-a-graphic-adaptation-online-10375792.webp)

Kp3hl [Free Pdf] a People's History of American Empire: the American Empire Project, a Graphic Adaptation Online

kp3hl [Free pdf] A People's History of American Empire: The American Empire Project, A Graphic Adaptation Online [kp3hl.ebook] A People's History of American Empire: The American Empire Project, A Graphic Adaptation Pdf Free Par Howard Zinn, Mike Konopacki, Paul Buhle *Download PDF | ePub | DOC | audiobook | ebooks Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook Détails sur le produit Rang parmi les ventes : #431639 dans eBooksPublié le: 2008-04-01Sorti le: 2008-04- 01Format: Ebook Kindle | File size: 78.Mb Par Howard Zinn, Mike Konopacki, Paul Buhle : A People's History of American Empire: The American Empire Project, A Graphic Adaptation before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised A People's History of American Empire: The American Empire Project, A Graphic Adaptation: Commentaires clientsCommentaires clients les plus utiles1 internautes sur 1 ont trouvé ce commentaire utile. L'Histoire de notre mondePar Jean Humbert gloupÉvidemment c'est un ouvrage très engagé à gauche. Normal son auteur est un activiste très à gauche (pour les États-Unis au moins) mais c'est, parait-il, un historien, un politologue de haut niveau. Le titre en lui-même ("l'Empire Américain") donne de suite le ton.Une précision, capitale, immédiatement : cet ouvrage est particulier : le livre de Zinn a été mis en bandes dessinées, avec sa participation.J'y ai découvert énormément de choses que j'ignorais (le massacre des grévistes dans le Colorado, l'accord USA-Espagne sur Cuba puis sur les Philippines, le bombardement au napalm de Royan pour "tester" une nouvelle arme, etc...) Effrayant.La thèse de l'auteur est que l'armée est au service de la finance et que ce duo dirige le monde, les prétentions humanitaires, sociales, vaguement paternalistes ne sont que des leurres. -

UE Workers in Chicago Facing Another Plant Closure

INDUSTRIAL OFFICIAL NEWSPAPER oF T H E I NDUS T R I A L Wo R K EWORKER R S O F T H E Wo R L D July 2009 #1717 Vol. 106 N o . 6 $1/ £ 1/ €1 More repression of Mexican workers Special: Wobbly art Massacre of ICE detainees stealing jobs? and poetry Indigenous in Peru 3 5 9 13 UE Workers in Chicago Facing Another Plant Closure By UE Local 1174 Workers at the Quad City Die Cast- The victory at Republic Windows ing plant in Moline, IL, which is slated and Doors Factory in Chicago would not to close on July 12, are facing the same have been possible without the support threat that the Republic workers faced: of thousands of people from around the being thrown out on the streets with world. We stood together in the face of nothing after years of hard work. This threats from bailed-out banks through plant closure could lead to a loss of 100 foreclosures, evictions and layoffs. A key jobs. piece of support was when international To fight this, the workers—who are unionists called the Bank of America members of UE Local 1174—are calling CEO and took action against local bank for local and international solidarity, branches. with action against Quad City Die Cast- The United Electrical, Radio and ing’s financier, Wells Fargo Bank. Machine Workers (UE) began a move- Wells Fargo received $25 billion ment exemplifying that with bold action in taxpayer money and immediately and support from around the country we planned a lavish retreat to Las Vegas in can win.