Disciplining Comics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Copyright 2013 Shawn Patrick Gilmore

Copyright 2013 Shawn Patrick Gilmore THE INVENTION OF THE GRAPHIC NOVEL: UNDERGROUND COMIX AND CORPORATE AESTHETICS BY SHAWN PATRICK GILMORE DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2013 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor Michael Rothberg, Chair Professor Cary Nelson Associate Professor James Hansen Associate Professor Stephanie Foote ii Abstract This dissertation explores what I term the invention of the graphic novel, or more specifically, the process by which stories told in comics (or graphic narratives) form became longer, more complex, concerned with deeper themes and symbolism, and formally more coherent, ultimately requiring a new publication format, which came to be known as the graphic novel. This format was invented in fits and starts throughout the twentieth century, and I argue throughout this dissertation that only by examining the nuances of the publishing history of twentieth-century comics can we fully understand the process by which the graphic novel emerged. In particular, I show that previous studies of the history of comics tend to focus on one of two broad genealogies: 1) corporate, commercially-oriented, typically superhero-focused comic books, produced by teams of artists; 2) individually-produced, counter-cultural, typically autobiographical underground comix and their subsequent progeny. In this dissertation, I bring these two genealogies together, demonstrating that we can only truly understand the evolution of comics toward the graphic novel format by considering the movement of artists between these two camps and the works that they produced along the way. -

2News Summer 05 Catalog

SAV THE BEST IN COMICS & E LEGO ® PUBLICATIONS! W 15 HEN % 1994 --2013 Y ORD OU ON ER LINE FALL 2013 ! AMERICAN COMIC BOOK CHRONICLES: The 1950 s BILL SCHELLY tackles comics of the Atomic Era of Marilyn Monroe and Elvis Presley: EC’s TALES OF THE CRYPT, MAD, CARL BARKS ’ Donald Duck and Uncle Scrooge, re-tooling the FLASH in Showcase #4, return of Timely’s CAPTAIN AMERICA, HUMAN TORCH and SUB-MARINER , FREDRIC WERTHAM ’s anti-comics campaign, and more! Ships August 2013 Ambitious new series of FULL- (240-page FULL-COLOR HARDCOVER ) $40.95 COLOR HARDCOVERS (Digital Edition) $12.95 • ISBN: 9781605490540 documenting each 1965-69 decade of comic JOHN WELLS covers the transformation of MARVEL book history! COMICS into a pop phenomenon, Wally Wood’s TOWER COMICS , CHARLTON ’s Action Heroes, the BATMAN TV SHOW , Roy Thomas, Neal Adams, and Denny O’Neil lead - ing a youth wave in comics, GOLD KEY digests, the Archies and Josie & the Pussycats, and more! Ships March 2014 (224-page FULL-COLOR HARDCOVER ) $39.95 (Digital Edition) $11.95 • ISBN: 9781605490557 The 1970s ALSO AVAILABLE NOW: JASON SACKS & KEITH DALLAS detail the emerging Bronze Age of comics: Relevance with Denny O’Neil and Neal Adams’s GREEN 1960-64: (224-pages) $39.95 • (Digital Edition) $11.95 • ISBN: 978-1-60549-045-8 LANTERN , Jack Kirby’s FOURTH WORLD saga, Comics Code revisions that opens the floodgates for monsters and the supernatural, 1980s: (288-pages) $41.95 • (Digital Edition) $13.95 • ISBN: 978-1-60549-046-5 Jenette Kahn’s arrival at DC and the subsequent DC IMPLOSION , the coming of Jim Shooter and the DIRECT MARKET , and more! COMING SOON: 1940-44, 1945-49 and 1990s (240-page FULL-COLOR HARDCOVER ) $40.95 • (Digital Edition) $12.95 • ISBN: 9781605490564 • Ships July 2014 Our newest mag: Comic Book Creator! ™ A TwoMorrows Publication No. -

Decoding the Visual Rhetoric: Memory and Trauma in Lynda Barry's One! Hundred! Demons!

http://wjel.sciedupress.com World Journal of English Language Vol. 8, No. 2; 2018 Decoding the Visual Rhetoric: Memory and Trauma in Lynda Barry’s One! Hundred! Demons! Partha Bhattacharjee & Priyanka Tripathi Department of Humanties and Social Sciences, Indian Institute of Technology Patna, India. Correspondence: E-mail: [email protected] Received: September 2, 2018 Accepted: September 20, 2018 Online Published: September 23, 2018 doi:10.5430/wjel.v8n2p37 URL: https://doi.org/10.5430/wjel.v8n2p37 Abstract Memory is an important tool in Lynda Barry’s One! Hundred! Demons! (2002) as she reconnoitres in non-linear fragments the personal trauma she faced while she was growing up. Layered into nineteen disjointed chapters, Barry’s graphic narrative is an amalgamation of images, collages and photographs, often following the pattern of a scrapbook style that justifies not only the events drawn in her narrative but also the motive of visual rhetoric in comics where visual images communicate and concretize meaning. Initially published as web comics (slate.com), each chapter consists of hand-painted vignettes of multifarious themes which are directly or indirectly linked to Barry’s life, covering from her childhood to adulthood. In the backdrop of these tools, techniques of visual rhetoric the objective of this paper is to investigate the form of the graphic narrative, the visual language employed in order to explore the traumatised childhood, memory and truth-telling in comics. Keywords: Trauma, Memory, Collage, Visual Language 1. Introduction Comics Studies emerges as a scholarly field in the second half of the 20th century and gains its boost to reach the acme in the current century. -

THE COMIX BOOK LIFE of DENIS KITCHEN Spring 2014 • the New Voice of the Comics Medium • Number 5 Table of Contents

THE COMIX BOOK LIFE OF DENIS KITCHEN 0 2 1 82658 97073 4 in theUSA $ 8.95 ADULTS ONLY! A TwoMorrows Publication TwoMorrows Cover art byDenisKitchen No. 5,Spring2014 ™ Spring 2014 • The New Voice of the Comics Medium • Number 5 TABLE OF CONTENTS HIPPIE W©©DY Ye Ed’s Rant: Talking up Kitchen, Wild Bill, Cruse, and upcoming CBC changes ............ 2 CBC mascot by J.D. KING ©2014 J.D. King. COMICS CHATTER About Our Bob Fingerman: The cartoonist is slaving for his monthly Minimum Wage .................. 3 Cover Incoming: Neal Adams and CBC’s editor take a sound thrashing from readers ............. 8 Art by DENIS KITCHEN The Good Stuff: Jorge Khoury on artist Frank Espinosa’s latest triumph ..................... 12 Color by BR YANT PAUL Hembeck’s Dateline: Our Man Fred recalls his Kitchen Sink contributions ................ 14 JOHNSON Coming Soon in CBC: Howard Cruse, Vanguard Cartoonist Announcement that Ye Ed’s comprehensive talk with the 2014 MOCCA guest of honor and award-winning author of Stuck Rubber Baby will be coming this fall...... 15 REMEMBERING WILD BILL EVERETT The Last Splash: Blake Bell traces the final, glorious years of Bill Everett and the man’s exquisite final run on Sub-Mariner in a poignant, sober crescendo of life ..... 16 Fish Stories: Separating the facts from myth regarding William Blake Everett ........... 23 Cowan Considered: Part two of Michael Aushenker’s interview with Denys Cowan on the man’s years in cartoon animation and a triumphant return to comics ............ 24 Art ©2014 Denis Kitchen. Dr. Wertham’s Sloppy Seduction: Prof. Carol L. Tilley discusses her findings of DENIS KITCHEN included three shoddy research and falsified evidence inSeduction of the Innocent, the notorious in-jokes on our cover that his observant close friends might book that almost took down the entire comic book industry .................................... -

Free Catalog

Featured New Items DC COLLECTING THE MULTIVERSE On our Cover The Art of Sideshow By Andrew Farago. Recommended. MASTERPIECES OF FANTASY ART Delve into DC Comics figures and Our Highest Recom- sculptures with this deluxe book, mendation. By Dian which features insights from legendary Hanson. Art by Frazetta, artists and eye-popping photography. Boris, Whelan, Jones, Sideshow is world famous for bringing Hildebrandt, Giger, DC Comics characters to life through Whelan, Matthews et remarkably realistic figures and highly al. This monster-sized expressive sculptures. From Batman and Wonder Woman to The tome features original Joker and Harley Quinn...key artists tell the story behind each paintings, contextualized extraordinary piece, revealing the design decisions and expert by preparatory sketches, sculpting required to make the DC multiverse--from comics, film, sculptures, calen- television, video games, and beyond--into a reality. dars, magazines, and Insight Editions, 2020. paperback books for an DCCOLMSH. HC, 10x12, 296pg, FC $75.00 $65.00 immersive dive into this SIDESHOW FINE ART PRINTS Vol 1 dynamic, fanciful genre. Highly Recommened. By Matthew K. Insightful bios go beyond Manning. Afterword by Tom Gilliland. Wikipedia to give a more Working with top artists such as Alex Ross, accurate and eye-opening Olivia, Paolo Rivera, Adi Granov, Stanley look into the life of each “Artgerm” Lau, and four others, Sideshow artist. Complete with fold- has developed a series of beautifully crafted outs and tipped-in chapter prints based on films, comics, TV, and ani- openers, this collection will mation. These officially licensed illustrations reign as the most exquisite are inspired by countless fan-favorite prop- and informative guide to erties, including everything from Marvel and this popular subject for DC heroes and heroines and Star Wars, to iconic classics like years to come. -

Free a Peoples History of American Empire Pdf

FREE A PEOPLES HISTORY OF AMERICAN EMPIRE PDF Howard Zinn | 288 pages | 30 May 2008 | Henry Holt & Company Inc | 9780805087444 | English | New York, NY, United States A People's History of American Empire: A Graphic Adaptation - Zinn Education Project Uh-oh, it looks like your Internet Explorer is out of date. For a better shopping experience, please upgrade now. Javascript is not enabled in your browser. Enabling JavaScript in your browser will allow you to experience all the features of our site. Learn how to enable JavaScript on your browser. NOOK Book. Questions for Discussion 1. One thing that sets this book apart, particularly as a work in the "graphic novel" genre, is its great variety of visual imagery. We find within these pages various photographs, maps, printed-page excerpts, diagrams, posters and poster-like advertisements, newspaper and magazine clippings, political cartoons, and, of course, many A Peoples History of American Empire both comics-based and realistic. Point out memorable examples of each A Peoples History of American Empire these categories. What is meant in this book by the word "empire"? Discuss this key term with your fellow students. Define "ghost dance. What does he mean when he states on page 17 : "The nation's hoop is broken and scattered"? The phrase A Peoples History of American Empire White Men" appears on more than one occasion A Peoples History of American Empire these pages. When, and in what context, does the phrase first appear? Who does this phrase signify, both specifically and generally? Eugene V. Debs makes his first appearance in this book on page Who was Debs? Why was he both revered and hated? For what is he best known today? And where else do we encounter him in these pages? How does it work? Where has it been utilized, over the years and across the globe? In the bottom panel of page 33, we see a maid or domestic servant waiting on a wealthy white person. -

Visitor Guide — Room 1

VISITOR GUIDE — ROOM 1 — THE SPIRIT OF WILL EISNER For its 10th Comics Biennial, the Thomas The one hundred works in this exhibition, Henry Museum is honouring one of the on loan from private collections, present the most influential authors of American comic major stages in the career of an author who books: Will Eisner (1917-2005). Will Eisner was focussed on elevating his discipline left an indelible mark on pop culture with to the rank it deserved, that of an art form The Spirit, a cult series which was to have in its own right. In the complete stories of an impact on the creativity of several The Spirit, Eisner’s very specific narration is generations, from the underground comix there to be discovered (or re-discovered): movement of the 1960s (Robert Crumb, plunge into the very dark atmosphere of Harvey Kurtzman) to the dark comics of the his flagship series, wander through his 1980s (Frank Miller, Alan Moore). theatrical sets and view New York City and the life of its most humble inhabitants from THE THOMAS HENRY MUSEUM Following the end of The Spirit in 1952, Will a different perspective. HAS ADAPTED TO THE CURRENT REGULATIONS RELATING Eisner pondered the theory of his art and TO THE HEALTH CRISIS AND IS OPEN TO THE PUBLIC. taught a ‘sequential art’ class, at the School of Visual Art in New York. After a long break, THIS EXHIBITION HAS BEEN CREATED IN PARTNERSHIP during which he was creating comics and WITH GALERIE 9e ART (REFERENCES). illustrations for educational purposes, he returned to the forefront of the comic book scene in 1978, inventing a new form of narration: the graphic novel. -

Comic Book Club Handbook

COMIC BOOK CLUB HANDBOOK Starting and making the most of book clubs for comics and graphic novels! STAFF COMIC BOOK LEGAL Charles Brownstein, Executive Director Alex Cox, Deputy Director DEFENSE FUND Samantha Johns, Development Manager Kate Jones, Office Manager Comic Book Legal Defense Fund is a non-profit organization Betsy Gomez, Editorial Director protecting the freedom to read comics! Our work protects Maren Williams, Contributing Editor readers, creators, librarians, retailers, publishers, and educa- Caitlin McCabe, Contributing Editor tors who face the threat of censorship. We monitor legislation Robert Corn-Revere, Legal Counsel and challenge laws that would limit the First Amendment. BOARD OF DIRECTORS We create resources that promote understanding of com- Larry Marder, President ics and the rights our community is guaranteed. Every day, Milton Griepp, Vice President Jeff Abraham, Treasurer we publish news and information about censorship events Dale Cendali, Secretary as they happen. We are partners in the Kids’ Right to Read Jennifer L. Holm Project and Banned Books Week. Our expert legal team is Reginald Hudlin Katherine Keller available at a moment’s notice to respond to First Amend- Paul Levitz ment emergencies. CBLDF is a lean organization that works Andrew McIntire hard to protect the rights that our community depends on. For Christina Merkler Chris Powell more information, visit www.cbldf.org Jeff Smith ADVISORY BOARD Neil Gaiman & Denis Kitchen, Co-Chairs CBLDF’s important Susan Alston work is made possible Matt Groening by our members! Chip Kidd Jim Lee Frenchy Lunning Join the fight today! Frank Miller Louise Nemschoff http://cbldf.myshopify Mike Richardson .com/collections William Schanes José Villarrubia /memberships Bob Wayne Peter Welch CREDITS CBLDF thanks our Guardian Members: Betsy Gomez, Designer and Editor James Wood Bailey, Grant Geissman, Philip Harvey, Joseph Cover and interior art by Rick Geary. -

E Hundred Demons Stephen E

162 Graphic Novels of Art Spiegelman © 2009 by The Modern Language Association of America. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. Second printing 2010 Teaching the alie op de Beeck Graphic Novel tobifictionalography: .uu.-u.ug Do in Lynda Barry's Edited by e Hundred Demons Stephen E. Tabachnick the far left margin of the copyright page to Lynda Barry's One 'Hu.w.ared Demons, hand-scrawled uppercase print advises, "Please note: is a work of autobifictionalography." Just beneath the table of con this word appears again in red, curly cursive lettering on torn green Barry's looping letters look approachable and greeting-card friendly. hand printing on another paper scrap asks the question, "A re stories 0 true or 0 fa lse?," with red check marks in each box to im- that these stories, perhaps all stories, are a li ttle of both. Barry pro a postmodern critical viewpoi nt in a noncombative way, encourag- genuine curiosity about the relation of autobiography to fiction and of to comics. She asks how well any written, drawn, or spoken ~LtmmL represents the truth, or a truth, and she playfully complicates The Modern Language Association of America by casting a semiautobiographical Lynda as her protagonist. Fur- New York 2009 she urges amateurs to write and illustrate work of their own, by tak up the Asian brushwork technique that inspired Demons in the first Michel de Certeau has ca lled "making do." Barry's combina of critical and creative inquiry-effectively demonstrating her own in an unaffected manner-makes Demons an excellent text for the and graduate classroom. -

AML 3285.0989 a Cultural History of American Women in Comics Fall 2017

AML 3285.0989 A Cultural History of American Women in Comics Fall 2017 Time: T 5-6, R 6 —► Tuesdays ll:45am-l :40pm, Thursdays 12:50pm-l :40pm Place:TUR 2318 Canvas Website:http://elearning.ufl.edu/ Course Website:https://americanwomenincomics.wordpress.com/ Instructor Name:Dr. Margaret Galvan Email:[email protected] Office: TUR 4348 Office Hours:Tuesdays 10:30am-11:30am, Thursdays 2:45pm-3:45pm, and by appointment Course Description: Despite a long history of female creators, readers, and nuanced characters, women’s participation in American comics has frequently been overlooked. Contemporary scholars have focused on recovering these forgotten women. In this class we will explore why women’s contributions have not been visible in comics histories. We will start by reading how comics have been variously defined. Reading these definitions alongside this understudied tradition of women’s comics, we will ask: is there something about the definitions that exclude women in comics? We will read comics by women in addition to reading comics for and about women, since female random and characters have also been minimized. We will read a variety of forms, both print and digital, and consider how we might wield this digital space to right the balance. Course assignments will include digital reflections on a shared course website, a short formal essay, and a research project that includes an annotated bibliography, proposal, Wikipedia edits, and formal paper. Books to Purchase: Lynda Barry, Syllabus (2014), Drawn & Quarterly, ISBN: 1770461612 Kate Beaton,Hark! A Ir agrant (2011), Drawn & Quarterly, ISBN: 1770460608 Thi Bui, The Best We Could Do (2017), Abrams, ISBN: 1419718770 Emil Ferris, My Favorite ThinglsMonsters (2017), Fantagraphics, ISBN: 1606999591 Cristy C. -

Feminist (And/As) Alternative Media Practices in Women’S Underground Comix in the 1970S1

Małgorzata Olsza Feminist (and/as) Alternative Media Practices in Women’s Underground Comix in the 1970s1 Abstract: The American underground comix scene in general, and women’s comix that flourished as a part of that scene in the 1970s in particular, grew out of and in response to the mainstream American comics scene, which, from its “Golden Age” to the 1970s, had been ruled and construed in accordance with commercial business practices and “assembly-line” processes. This article discusses underground comix created by women in the 1970s in the wider context of alternative and second-wave feminist media practices. I explain how women’s comix used “activist aesthetics” and parodic poetics, combining a radical political and social message with independent publishing and distributive networks. Keywords: American comics, American comix, women’s comix, feminist art and theory, media practices Introduction Toughly mainly associated with popular culture, mass production, and thus consumerism, the history of comics also intertwines with the history of the American counterculture and feminism. In the present article, I examine women’s underground comix from the 1970s as a product and an integral element of a complex and dynamic network of historical, cultural, and social factors, including the mainstream comics industry, men’s underground comix, and alternative media practices, demonstrating how the media practices adopted by female comix authors were used to promote the ideals of second-wave feminism. As Elke Zobl and Ricarda Drüeke point out in Feminist Media, “[u]sing media to transport their messages, to disrupt social orders and to spin novel social processes, feminists have long recognized the importance of self-managed, alternative media” (11). -

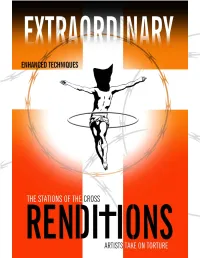

Torture of Detainees, and Summary Executions

Table of Contents 1 Introduction 2 STATION I: Jesus Is Condemned to Death Michael Connors 4 STATION II: Jesus Carries His Cross John Hitchcock 6 STATION III: Jesus Falls the First Time Michael Duffy 8 STATION IV: Jesus Meets His Mother Colm McCarthy 10 STATION V: Simon Helps Jesus Carry His Cross Miguel A. Peña 12 STATION VI: Veronica Wipes the Face of Jesus Mike Konopacki 14 STATION VII: Jesus Falls the Second Time Miguel A. Peña 16 STATION VIII: Jesus Meets the Pious Women of Jerusalem Colm McCarthy 18 STATION IX: Jesus Falls the Third Time Lester Doré 20 STATION X: Jesus Is Stripped of His Garments Steve Chappell 22 STATION XI: Jesus Is Nailed to the Cross Pamela Cremer 24 STATION XII: Jesus Dies on the Cross Mike Konopacki 26 STATION XIII: Jesus Is Taken Down from the Cross Quincy Neri 28 STATION XIV: Jesus Is Laid in the Tomb Lester Doré Extraordinary Renditions ince 9/11, the US empire has been embroiled in a “War on Terror” against Islamic fundamentalism. All sides in this “war” have used religious justification for the most Sheinous of crimes: mass killings of innocent civilians, torture of detainees, and summary executions. Fundamentalists of the three Abrahamic religions — Judaism, Christianity, and Islam — have rejected traditions of peace to wage “jihad” and “just war.” As citizen artists in an empire, we feel compelled to protest our government’s criminality and the failure of major religious, medical, and legal associations to speak out against these atrocities. Decisions to torture detainees to elicit information came directly from George W.