Coping with Memory Loss

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Compare and Contrast Two Models Or Theories of One Cognitive Process with Reference to Research Studies

! The following sample is for the learning objective: Compare and contrast two models or theories of one cognitive process with reference to research studies. What is the question asking for? * A clear outline of two models of one cognitive process. The cognitive process may be memory, perception, decision-making, language or thinking. * Research is used to support the models as described. The research does not need to be outlined in a lot of detail, but underatanding of the role of research in supporting the models should be apparent.. * Both similarities and differences of the two models should be clearly outlined. Sample response The theory of memory is studied scientifically and several models have been developed to help The cognitive process describe and potentially explain how memory works. Two models that attempt to describe how (memory) and two models are memory works are the Multi-Store Model of Memory, developed by Atkinson & Shiffrin (1968), clearly identified. and the Working Memory Model of Memory, developed by Baddeley & Hitch (1974). The Multi-store model model explains that all memory is taken in through our senses; this is called sensory input. This information is enters our sensory memory, where if it is attended to, it will pass to short-term memory. If not attention is paid to it, it is displaced. Short-term memory Research. is limited in duration and capacity. According to Miller, STM can hold only 7 plus or minus 2 pieces of information. Short-term memory memory lasts for six to twelve seconds. When information in the short-term memory is rehearsed, it enters the long-term memory store in a process called “encoding.” When we recall information, it is retrieved from LTM and moved A satisfactory description of back into STM. -

Psychogenic and Organic Amnesia. a Multidimensional Assessment of Clinical, Neuroradiological, Neuropsychological and Psychopathological Features

Behavioural Neurology 18 (2007) 53–64 53 IOS Press Psychogenic and organic amnesia. A multidimensional assessment of clinical, neuroradiological, neuropsychological and psychopathological features Laura Serraa,∗, Lucia Faddaa,b, Ivana Buccionea, Carlo Caltagironea,b and Giovanni A. Carlesimoa,b aFondazione IRCCS Santa Lucia, Roma, Italy bClinica Neurologica, Universita` Tor Vergata, Roma, Italy Abstract. Psychogenic amnesia is a complex disorder characterised by a wide variety of symptoms. Consequently, in a number of cases it is difficult distinguish it from organic memory impairment. The present study reports a new case of global psychogenic amnesia compared with two patients with amnesia underlain by organic brain damage. Our aim was to identify features useful for distinguishing between psychogenic and organic forms of memory impairment. The findings show the usefulness of a multidimensional evaluation of clinical, neuroradiological, neuropsychological and psychopathological aspects, to provide convergent findings useful for differentiating the two forms of memory disorder. Keywords: Amnesia, psychogenic origin, organic origin 1. Introduction ness of the self – and a period of wandering. According to Kopelman [33], there are three main predisposing Psychogenic or dissociative amnesia (DSM-IV- factors for global psychogenic amnesia: i) a history of TR) [1] is a clinical syndrome characterised by a mem- transient, organic amnesia due to epilepsy [52], head ory disorder of nonorganic origin. Following Kopel- injury [4] or alcoholic blackouts [20]; ii) a history of man [31,33], psychogenic amnesia can either be sit- psychiatric disorders such as depressed mood, and iii) uation specific or global. Situation specific amnesia a severe precipitating stress, such as marital or emo- refers to memory loss for a particular incident or part tional discord [23], bereavement [49], financial prob- of an incident and can arise in a variety of circum- lems [23] or war [21,48]. -

Types of Memory and Models of Memory

Inf1: Intro to Cognive Science Types of memory and models of memory Alyssa Alcorn, Helen Pain and Henry Thompson March 21, 2012 Intro to Cognitive Science 1 1. In the lecture today A review of short-term memory, and how much stuff fits in there anyway 1. Whether or not the number 7 is magic 2. Working memory 3. The Baddeley-Hitch model of memory hEp://www.cartoonstock.com/directory/s/ short_term_memory.asp March 21, 2012 Intro to Cognitive Science 2 2. Review of Short-Term Memory (STM) Short-term memory (STM) is responsible for storing small amounts of material over short periods of Nme A short Nme really means a SHORT Nme-- up to several seconds. Anything remembered for longer than this Nme is classified as long-term memory and involves different systems and processes. !!! Note that this is different that what we mean mean by short- term memory in everyday speech. If someone cannot remember what you told them five minutes ago, this is actually a problem with long-term memory. While much STM research discusses verbal or visuo-spaal informaon, the disNncNon of short vs. long-term applies to other types of sNmuli as well. 3/21/12 Intro to Cognitive Science 3 3. Memory span and magic numbers Amount of informaon varies with individual’s memory span = longest number of items (e.g. digits) that can be immediately repeated back in correct order. Classic research by George Miller (1956) described the apparent limits of short-term memory span in one of the most-cited papers in all of psychology. -

What Is It Like to Be Confabulating?

What is it like to be Confabulating? Sahba Besharati, Aikaterini Fotopoulou and Michael D. Kopelman Kings College London, Institute of Psychiatry, London UK Different kinds of confabulations may arise in neurological and psychiatric disorders. This chapter first offers conceptual distinctions between spontaneous and momentary (“provoked”) confabulations, as well as between these types of confabulation and other kinds of false memories. The chapter then reviews current explanatory theories, emphasizing that both neurocognitive and motivational factors account for the content of confabulations. We place particular emphasis on a general model of confabulation that considers cognitive dysfunctions in memory and executive functioning in parallel with social and emotional factors. It is argued that all these dimensions need to be taken into account for a phenomenologically rich description of confabulation. The role of the motivated content of confabulation and the subjective experience of the patient are particularly relevant in effective management and rehabilitation strategies. Finally, we discuss a case example in order to illustrate how seemingly meaningless false memories are actually meaningful if placed in the context of the patient’s own perspective and autobiographical memory. Key words: Confabulation; False memory; Motivation; Self; Rehabilitation. 1 Memory is often subject to errors of omission and commission such that recollection includes instances of forgetting, or distorting past experience. The study of pathological forms of exaggerated memory distortion has provided useful insights into the mechanisms of normal reconstructive remembering (Johnson, 1991; Kopelman, 1999; Schacter, Norman & Kotstall, 1998). An extreme form of pathological memory distortion is confabulation. Different variants of confabulation are found to arise in neurological and psychiatric disorders. -

Handbook of Metamemory and Memory Evolution of Metacognition

This article was downloaded by: 10.3.98.104 On: 29 Sep 2021 Access details: subscription number Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: 5 Howick Place, London SW1P 1WG, UK Handbook of Metamemory and Memory John Dunlosky, Robert A. Bjork Evolution of Metacognition Publication details https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/doi/10.4324/9780203805503.ch3 Janet Metcalfe Published online on: 28 May 2008 How to cite :- Janet Metcalfe. 28 May 2008, Evolution of Metacognition from: Handbook of Metamemory and Memory Routledge Accessed on: 29 Sep 2021 https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/doi/10.4324/9780203805503.ch3 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR DOCUMENT Full terms and conditions of use: https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/legal-notices/terms This Document PDF may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproductions, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The publisher shall not be liable for an loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material. Evolution of Metacognition Janet Metcalfe Introduction The importance of metacognition, in the evolution of human consciousness, has been emphasized by thinkers going back hundreds of years. While it is clear that people have metacognition, even when it is strictly defined as it is here, whether any other animals share this capability is the topic of this chapter. -

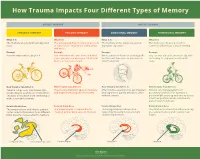

How Trauma Impacts Four Different Types of Memory

How Trauma Impacts Four Different Types of Memory EXPLICIT MEMORY IMPLICIT MEMORY SEMANTIC MEMORY EPISODIC MEMORY EMOTIONAL MEMORY PROCEDURAL MEMORY What It Is What It Is What It Is What It Is The memory of general knowledge and The autobiographical memory of an event The memory of the emotions you felt The memory of how to perform a facts. or experience – including the who, what, during an experience. common task without actively thinking and where. Example Example Example Example You remember what a bicycle is. You remember who was there and what When a wave of shame or anxiety grabs You can ride a bicycle automatically, with- street you were on when you fell off your you the next time you see your bicycle out having to stop and recall how it’s bicycle in front of a crowd. after the big fall. done. How Trauma Can Affect It How Trauma Can Affect It How Trauma Can Affect It How Trauma Can Affect It Trauma can prevent information (like Trauma can shutdown episodic memory After trauma, a person may get triggered Trauma can change patterns of words, images, sounds, etc.) from differ- and fragment the sequence of events. and experience painful emotions, often procedural memory. For example, a ent parts of the brain from combining to without context. person might tense up and unconsciously make a semantic memory. alter their posture, which could lead to pain or even numbness. Related Brain Area Related Brain Area Related Brain Area Related Brain Area The temporal lobe and inferior parietal The hippocampus is responsible for The amygdala plays a key role in The striatum is associated with producing cortex collect information from different creating and recalling episodic memory. -

Vascular Dementia Vascular Dementia

Vascular Dementia Vascular Dementia Other Dementias This information sheet provides an overview of a type of dementia known as vascular dementia. In this information sheet you will find: • An overview of vascular dementia • Types and symptoms of vascular dementia • Risk factors that can put someone at risk of developing vascular dementia • Information on how vascular dementia is diagnosed and treated • Information on how someone living with vascular dementia can maintain their quality of life • Other useful resources What is dementia? Dementia is an overall term for a set of symptoms that is caused by disorders affecting the brain. Someone with dementia may find it difficult to remember things, find the right words, and solve problems, all of which interfere with daily activities. A person with dementia may also experience changes in mood or behaviour. As the dementia progresses, the person will have difficulties completing even basic tasks such as getting dressed and eating. Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia are two common types of dementia. It is very common for vascular dementia and Alzheimer’s disease to occur together. This is called “mixed dementia.” What is vascular dementia?1 Vascular dementia is a type of dementia caused by damage to the brain from lack of blood flow or from bleeding in the brain. For our brain to function properly, it needs a constant supply of blood through a network of blood vessels called the brain vascular system. When the blood vessels are blocked, or when they bleed, oxygen and nutrients are prevented from reaching cells in the brain. As a result, the affected cells can die. -

A Patient's Guide to Parkinson's Disease Dementia (PDD)

A Patient’s Guide to Parkinson’s Disease Dementia (PDD) This material is provided by UCSF Weill Institute for Neurosciences as an educational resource for patients. Models for illustrative purposes only. A patient’s guide to Parkinson’s Disease Dementia (PDD) What is dementia? eventually parts of the brain that are important for mental functions such as memory and thinking become injured. Dementia is a general term for any disease that causes a change in memory and/or thinking skills that is severe enough to impair How is age related to PDD? a person’s daily functioning. Symptoms of dementia vary from Both PD and PDD are more common with increasing age. Most person to person and may affect one’s ability to remember things, people with PD start having movement symptoms between ages concentrate, plan and organize, communicate or find one’s way 50 and 85, although some people have shown signs earlier. Up to around, among other possible symptoms. There are many causes 80% of people with PD eventually develop dementia. The average of dementia and Parkinson’s disease can be one of them. Not at all time from onset of movement problems to development people with Parkinson’s disease develop dementia. of dementia is about 10 years. What is Parkinson’s disease dementia? What happens in PDD? Parkinson’s disease dementia (PDD) is changes in thinking and People with PDD may have trouble focusing, remembering things, behavior in someone with a diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease (PD). or making sound judgments. They may develop depression, anxiety PD is an illness characterized by gradually progressive problems or irritability. -

Memory-Modulation: Self-Improvement Or Self-Depletion?

HYPOTHESIS AND THEORY published: 05 April 2018 doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00469 Memory-Modulation: Self-Improvement or Self-Depletion? Andrea Lavazza* Neuroethics, Centro Universitario Internazionale, Arezzo, Italy Autobiographical memory is fundamental to the process of self-construction. Therefore, the possibility of modifying autobiographical memories, in particular with memory-modulation and memory-erasing, is a very important topic both from the theoretical and from the practical point of view. The aim of this paper is to illustrate the state of the art of some of the most promising areas of memory-modulation and memory-erasing, considering how they can affect the self and the overall balance of the “self and autobiographical memory” system. Indeed, different conceptualizations of the self and of personal identity in relation to autobiographical memory are what makes memory-modulation and memory-erasing more or less desirable. Because of the current limitations (both practical and ethical) to interventions on memory, I can Edited by: only sketch some hypotheses. However, it can be argued that the choice to mitigate Rossella Guerini, painful memories (or edit memories for other reasons) is somehow problematic, from an Università degli Studi Roma Tre, Italy ethical point of view, according to some of the theories of the self and personal identity Reviewed by: in relation to autobiographical memory, in particular for the so-called narrative theories Tillmann Vierkant, University of Edinburgh, of personal identity, chosen here as the main case of study. Other conceptualizations of United Kingdom the “self and autobiographical memory” system, namely the constructivist theories, do Antonella Marchetti, Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, not have this sort of critical concerns. -

Metamemory and Memory Discrepancies in Directed Forgetting of Emotional Information

Research Reports Metamemory and Memory Discrepancies in Directed Forgetting of Emotional Information Dicle Çapan a, Simay Ikier b [a] Department of Psychology, Koç University, Istanbul, Turkey. [b] Department of Psychology, Bahçeşehir University, Istanbul, Turkey. Europe's Journal of Psychology, 2021, Vol. 17(1), 44–52, https://doi.org/10.5964/ejop.2567 Received: 2019-12-17 • Accepted: 2020-04-23 • Published (VoR): 2021-02-26 Handling Editor: Rhian Worth, University of South Wales, Pontypridd, United Kingdom Corresponding Author: Dicle Çapan, Koç University, Rumelifeneri Mahallesi, Sarıyer Rumeli Feneri Yolu, 34450 Sarıyer Istanbul, Turkey. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Directed Forgetting (DF) studies show that it is possible to exert cognitive control to intentionally forget information. The aim of the present study was to investigate how aware individuals are of the control they have over what they remember and forget when the information is emotional. Participants were presented with positive, negative and neutral photographs, and each photograph was followed by either a Remember or a Forget instruction. Then, for each photograph, participants provided Judgments of Learning (JOLs) by indicating their likelihood of recognizing that item on a subsequent test. In the recognition phase, participants were asked to indicate all old items, irrespective of instruction. Remember items had higher JOLs than Forget items for all item types, indicating that participants believe they can intentionally forget even emotional information—which is not the case based on the actual recognition results. DF effect, which was calculated by subtracting recognition for Forget items from Remember ones was only significant for neutral items. Emotional information disrupted cognitive control, eliminating the DF effect. -

Mild Cognitive Impairment Or Dementia

What To Know When You Have Mild Cognitive Impairment or Dementia People who are told they have mild cognitive impairment (MCI) experience symptoms that are similar to dementia, but aren’t as serious. People with MCI have changes in memory or thinking typically poorer than would be expected for someone their age, but the changes don’t interfere with daily activities. It should be noted that people with MCI have a higher risk of developing dementia, but not all will. Dementia is an umbrella term to describe symptoms that are severe enough to interfere with daily activities. The most common cause of dementia in older adults is Alzheimer’s disease. Other causes include Lewy body dementia, vascular dementia and Frontotemporal diseases. A diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease or a related disorder doesn’t change who you are and it doesn’t mean you need to stop doing things you find meaningful. It does mean that over time you might have to do them in a different way or have some assistance. The disease does not affect the entire brain all at once. Many areas of the brain are not affected, or are affected much later. Important Messages Dementia can affect memory, We All Should Know thinking, communication and doing everyday tasks. Dementia is not a natural part of aging. It’s possible to live well with dementia. Dementia is caused by diseases of the brain and will There is more to a person affect each person differently. than the dementia. Ways to Work With Mild Cognitive Impairment or Dementia 1 6 Stop multi-tasking. -

CHAPTER 6: MEMORY STRATEGIES: MNEMONIC DEVICES in Order to Remember Information, You First Have to Find It Somewhere in Your Memory

CHAPTER 6: MEMORY STRATEGIES: MNEMONIC DEVICES In order to remember information, you first have to find it somewhere in your memory. To be successful in college you need to use active learning strategies that help you store information and retrieve it. Mnemonic devices can help you do that. Mnemonics are techniques for remembering information that is otherwise difficult to recall. The idea behind using mnemonics is to encode complex information in a way that is much easier to remember. Two common types of mnemonic devices are acronyms and acrostics. Acronyms Acronyms are words made up of the first letters of other words. As a mnemonic device, acronyms help you remember the first letters of items in a list, which in turn helps you remember the list itself. Instructor OLC to accompany 100% Online Student Success 1 Examples The following are examples of popular mnemonic acronyms: HOMES Huron, Ontario, Michigan, Erie, Superior Names of the Great Lakes FACE The letters of the treble clef notes in the spaces from bottom to top spells “FACE”. ROY G. BIV Red, Orange, Yellow, Green, Blue, Indigo, Colors of the spectrum Violet MRS GREN Movement, Respiration, Sensitivity, Growth, Common attributes of living Reproduction, Excretion, Nutrition things Create Your Own Acronym Now think of a few words you need to remember. This could be related to your studies, your work, or just a subject of interest. Five steps to creating acronyms are*: 1. List the information you need to learn in meaningful phrases. 2. Circle or underline a keyword in each phrase. 3. Write down the first letter of each keyword.