Explanations of the Grounds of Nullity Defects Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Texas Nepotism Laws Made Easy

Texas Nepotism Laws Made Easy 2016 Editor Zindia Thomas Assistant General Counsel Texas Municipal League www.tml.org Updated July 2016 Table of Contents 1. What is nepotism? .................................................................................................................... 1 2. What types of local government officials are subject to the nepotism laws? .......................... 1 3. What types of actions are generally prohibited under the nepotism law? ............................... 1 4. What relatives of a public official are covered by the statutory limitations on relationships by consanguinity (blood)? .................................................................................. 1 5. What relationships by affinity (marriage) are covered by the statutory limitations? .............. 2 6. What happens if it takes two marriages to establish the relationship with the public official? ......................................................................................................................... 3 7. What actions must a public official take if he or she has a nepotism conflict? ....................... 3 8. Do the nepotism laws apply to cities with a population of less than 200? .............................. 3 9. May a close relative be appointed to an unpaid position? ....................................................... 3 10. May other members of a governing body vote to hire a person who is a close relative of a public official if the official with the nepotism conflict abstains from deliberating and/or -

Diaconal Policies for the Ordained

POLICY MANUAL FOR THE DIACONATE DIOCESE OF BEAUMONT (12-1-1997) (Rev. 8-1-2012) INTRODUCTION TO DIOCESAN POLICIES REGARDING THE DIACONATE The Second Vatican Council restored the diaconate to the Latin Church "as a proper and permanent rank of the hierarchy" (cf. Lumen Gentium, #29) This vocation to the diaconate is a great gift of God to the Church and for this reason is "an important enrichment for the Church's mission" (cf. Catechism of the Catholic Church #1571). "Catholic doctrine, expressed in liturgy, Magisterium and the constant practice of the Church, recognizes that there are two degrees of ministerial participation in the priesthood of Christ: the episcopacy and the presbyterate. The diaconate is intended to help and serve them.... Catholic doctrine also teaches that the degrees of priestly participation (episcopate and presbyterate) and the degree of service (diaconate) are all three conferred by a sacramental act called 'ordination', that is, by the Sacrament of Holy Orders" (cf. Catechism of the Catholic Church #1554). By the imposition of the Bishop's hands and the specific prayer of consecration, the Deacon receives a particular configuration to Christ, the Head and shepherd of the Church, who, for love of the Father, made himself the least and the servant of all (cf. Mk 10: 43-45; Mt 20:28; 1 Pt 5:3). Sacramental grace gives Deacons the necessary strength to serve the People of God in the "diakonia" of liturgy, of the Word and of charity, in communion with the Bishop and his presbyterate (cf. Catechism of the Catholic Church, # 1588). -

Stages of Papal Law

Journal of the British Academy, 5, 37–59. DOI https://doi.org/10.5871/jba/005.037 Posted 00 March 2017. © The British Academy 2017 Stages of papal law Raleigh Lecture on History read 1 November 2016 DAVID L. D’AVRAY Fellow of the British Academy Abstract: Papal law is known from the late 4th century (Siricius). There was demand for decretals and they were collected in private collections from the 5th century on. Charlemagne’s Admonitio generalis made papal legislation even better known and the Pseudo-Isidorian collections brought genuine decretals also to the wide audience that these partly forged collections reached. The papal reforms from the 11th century on gave rise to a new burst of papal decretals, and collections of them, culminating in the Liber Extra of 1234. The Council of Trent opened a new phase. The ‘Congregation of the Council’, set up to apply Trent’s non-dogmatic decrees, became a new source of papal law. Finally, in 1917, nearly a millennium and a half of papal law was codified by Cardinal Gasparri within two covers. Papal law was to a great extent ‘demand- driven’, which requires explanation. The theory proposed here is that Catholic Christianity was composed of a multitude of subsystems, not planned centrally and each with an evolving life of its own. Subsystems frequently interfered with the life of other subsystems, creating new entanglements. This constantly renewed complexity had the function (though not the purpose) of creating and recreating demand for papal law to sort out the entanglements between subsystems. For various reasons other religious systems have not generated the same demand: because the state plays a ‘papal’ role, or because the units are small, discrete and simple, or thanks to a clear simple blueprint, or because of conservatism combined with a tolerance of some inconsistency. -

Myths About Marriage Annulments in the Catholic Church

Myths about marriage annulments in the Catholic Church Reverend Langes J. Silva, JCD, STL Judicial Vicar/Vice-Chancellor Diocese of Salt Lake City Part I The exercise of functions in the Roman Catholic Church is divided in three branches: executive, legislative and judicial. The judicial function in every diocese is exercised by the Diocesan Bishop and his legitimate delegate, the Judicial Vicar in the office of the Diocesan Tribunal. The Judicial Vicar, a truly expert in Canon Law, assisted by a number of Judges, Defenders of the Bond, a Promoter of Justice, Notaries and Canonical Advocates, exercises the judicial function by conducting all canonical trials and procedures. The Roman Catholic Church has taken significant steps, especially after the Second Vatican Council and the review of the Code of Canon Law, to ensure fair, yet efficient, procedures, to those wishing to exercise their rights under canon law; for example, when seeking an ecclesiastical annulment, when all hopes of restoring common life have been exhausted or when, indeed, there was a judicial factor affecting the validity of the celebration of marriage. This presentation “Myths about declarations of invalidity of marriage (Annulments) in the Catholic Church” is organized as a series of twelve parts reflecting on fifteen common myths or misunderstandings about the annulment process. I do argue that the current system is a wonderful tool, judicially and pastorally speaking, for people to wish to restore their status in the Church, in order to help those who feel it has -

Legislating First Cousin Marriage in the Progressive Era

KISSING COUSINS: LEGISLATING FIRST COUSIN MARRIAGE IN THE PROGRESSIVE ERA Lori Jean Wilson Consanguineous or close-kin marriages are older than history itself. They appear in the religious texts and civil records of the earliest known societies, both nomadic and sedentary. Examples of historical cousin-marriages abound. However, one should not assume that consanguineous partnerships are archaic or products of a bygone era. In fact, Dr. Alan H. Bittles, a geneticist who has studied the history of cousin-marriage legislation, reported to the New York Times in 2009 that first-cousin marriages alone account for 10 percent of global marriages.1 As of 2010, twenty-six states in the United States permit first cousin marriage. Despite this legal acceptance, the stigma attached to first-cousin marriage persists. Prior to the mid- nineteenth century, however, the American public showed little distaste toward the practice of first cousin marriage. A shift in scientific opinion emerged in the mid-nineteenth century and had anthropologists questioning whether the custom had a place in western civilization or if it represented a throwback to barbarism. The significant shift in public opinion however, occurred during the Progressive Era as the discussion centered on genetics and eugenics. The American public vigorously debated whether such unions were harmful or beneficial to the children produced by first cousin unions. The public also debated what role individual states, through legislation, should take in restricting the practice of consanguineous marriages. While divergent opinions emerged regarding the effects of first cousin marriage, the creation of healthy children and a better, stronger future generation of Americans remained the primary goal of Americans on both sides of the debate. -

Canonical Procedures

CANONICAL PROCEDURES MARRIAGE, SACRAMENTAL RECORDS, ASCRIPTION TO CHURCHES SUI IURIS Diocese of Cleveland CANONICAL PROCEDURES MARRIAGE, SACRAMENTAL RECORDS, ASCRIPTION TO CHURCHES SUI IURIS April 2014 (minor revisions September 2016) THE TRIBUNAL OF THE DIOCESE OF CLEVELAND 1404 East Ninth Street, Seventh Floor Cleveland, OH 44114-2555 Phone: 216-696-6525, extension 4000 Fax: 216-696-3226 Website: www.dioceseofcleveland.org/tribunal CANONICAL PROCEDURES TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ..................................................................................................................................... V FOREWORD .................................................................................................................................................. IX PURPOSE OF THIS BOOKLET ......................................................................................................................... XI I. THE PRE-NUPTIAL FILE ............................................................................................................................... 1 A. INFORMATION FOR MARRIAGE FORM .................................................................................................................. 1 1. Spiritual and Personal Assessment Sections ........................................................................................... 1 2. Canonical Assessment Section ................................................................................................................ 1 3. Marriage Outside of Proper -

Quick Guidelines

There is no guarantee that an affirmative 6. The promises (cautiones) must be signed by both decision will be reached. Therefore, no date for a the Catholic and non-Catholic party should a subsequent marriage should ever be set until the case dispensation for disparity of worship or permission is concluded and the decision is ratified. for mixed religion be required for the proposed new marriage. 7. Efforts must be made to secure the present OTHER TYPES OF CASES whereabouts and testimony of the Respondent. 8. A Catholic Petitioner must do everything possible to ensure the religious education of the children PAULINE PRIVILEGE from the former marriage. Archdiocese of Los Angeles 9. The principles of justice toward the previous Metropolitan Tribunal Pauline Privilege refers to the dissolution of spouse and any children of the former marriage a marriage between two unbaptized persons. must be fulfilled by the Petitioner. 10. The Catholic parties must seriously practice their To invoke the Pauline Privilege: Faith. a. Both parties must have been unbaptized at the time of marriage, and the other party must still be unbaptized. PRIOR BOND (LIGAMEN) QUICK b. Proof of non-baptism of both parties at the time of the marriage must be established. Ligamen, or prior bond, is one of the GUIDELINES c. The Petitioner must sincerely seek to be baptized. impediments to marriage in the Church and causes the d. The other party does not intend to be baptized and existing marriage to be invalid. does not wish to be reconciled with the Petitioner. One or both parties have a prior valid marriage that has/have not ended by the death of the UNDERSTANDING former spouse, and the church has not issued an THE PROCESS OF FAVOR OF THE FAITH affirmative decision on the nullity of the prior marriage(s). -

Ligamen 2015

LIGAMEN PETITION #________________________ (Prior Valid Bond) Please type or print clearly. It is important that each item have a response. If a question is not applicable, write “N/A.” If you do not know an answer, write “unknown.” PETITIONER RESPONDENT ______________________________________________PRESENT LAST NAME________________________________________________ __________________________________________________MAIDEN NAME__________________________________________________ _____________________________________________FIRST AND MIDDLE NAMES___________________________________________ ________________________________________________STREET ADDRESS_________________________________________________ ________________________________________________CITY / STATE / ZIP_________________________________________________ __________________________________________________TELEPHONE____________________________________________________ Home Work Cell Home Work Cell ___________________________________________DATE AND PLACE OF BIRTH_____________________________________________ RELIGION OF BAPTISM RELIGION PROFESSED AT TIME OF WEDDING PRESENT RELIGION 1. Date and Place of Wedding Date City State 2. By a [ ] non-Catholic Minister [ ] Justice of the Peace in Name of Church, Synagogue, Courthouse, Home, Other 3. Date and Place of Divorce Date Court Parish/County State 4. This was my first marriage [ ] YES [ ] NO; If NO, ON ANOTHER SHEET OF PAPER, please list ALL your previous marriages with the name and religion of spouse, wedding date, place, when and how each -

MANUAL of POLICY Title Nepotism: Public Officials 1512 Legal

MANUAL OF POLICY Title Nepotism: Public Officials 1512 Legal Authority Approval of the Board of Trustees Page 1 of 2 Date Approved by Board Board Minute Order dated November 26, 2019 I. Purpose The purpose of this policy is to provide provisions regarding nepotism prohibition of public officials as defined by the consanguinity and affinity relationship. II. Policy A. Nepotism Prohibitions Applicable to Public Officials As public officials, the members of the Board of Trustees and the College President are subject to the nepotism prohibitions of Chapter 573 of the Texas Government Code. South Texas College shall not employ any person related within the second degree by affinity (marriage) or within the third degree by consanguinity (blood) to any member of the Board or the College President when the salary, fees, or compensation of the employee is paid from public funds or fees of office. A nepotism prohibition is not applicable to the employment of an individual with the College if: 1) the individual is employed in the position immediately before the election or appointment of the public official to whom the individual is related in a prohibited degree; and 2) that prior employment of the individual is continuous for at least: a. 30 days, if the public official is appointed; b. six months, if the public official is elected at an election other than the general election for state and county officers; or c. one year, if the public official is elected at the general election for state and county officers. If an individual whose employment is not subject to the nepotism prohibition continues in a position, the College President or the member of the Board of Trustees to whom the individual is related in a prohibited degree may not participate in any deliberation or voting on the employment, reemployment, change in status, compensation, or dismissal of the individual if that action applies only to the individual and is not taken regarding a bona fide class or category of employees. -

The Revision of Canon Law: Theological Implications Thomas J

THE REVISION OF CANON LAW: THEOLOGICAL IMPLICATIONS THOMAS J. GREEN The Catholic University of America HE SECOND Vatican Council profoundly desired to bring the Church Tup to date (aggiornamento) and make it a more vital instrument of God's saving presence in a rapidly changing world. Crucial to the revital- ization of the Church's mission was the reform of its institutional struc tures. Understandably, then, a significant aspect of postconciliar reform has been an unprecedented effort to reform canon law. Indeed, the time- honored relationship between total ecclesial renewal and canonical reform was recognized by Pope John XXIII in his calling for the revision of canon law as early as January 1959, when he announced the forthcoming Second Vatican Council.1 Two decades have elapsed since that initial call for canonical reform, and the process of revising the Code of Canon Law (henceforth Code) seems to have reached a critical stage. A consideration of some key moments in that process should help one gain a better perspective on the present status of canonical reform.2 The Pontifical Commission for the Revision of the Code of Canon Law (henceforth Code Commission) was established by John XXIII on March 20, 1963.3 However, it began to function only after the Council, since a principal aspect of its mandate was to reform the Code in light of conciliar principles. Only then could the Code be an instrument finely adapted to the Church's life and mission.4 On November 20, 1965 Pope Paul VI 1 See AAS 51 (1959) 65-69. See also J. -

Third Degree of Consanguinity

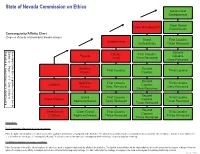

State of Nevada Commission on Ethics Great-Great Grandparents 4 Great Grand Great Grandparents Uncles/Aunts Consanguinity/Affinity Chart 3 5 (Degrees of family relationship by blood/marriage) Grand First Cousins Grandparents Uncles/Aunts Twice Removed 2 4 6 Second Uncles First Cousins Parents Cousins Aunts Once Removed 1 3 5 Once Removed 7 Brothers Second First Cousins Third Cousins Sisters Cousins 2 4 6 8 Second Nephews First Cousins Third Cousins Children Cousins Nieces Once Removed Once Removed 1 3 5 Once Removed 7 9 Second Grand First Cousins Third Cousins Grand Children Cousins Nephews/Nieces Twice Removed Twice Removed 1 2 4 6 Twice Removed 8 0 Second Great Grand Great Grand First Cousins Third Cousins Cousins Children Nephews/Nieces Thrice Removed Thrice Removed 1 3 5 7 Thrice Removed 9 1 Instructions: For Consanguinity (relationship by blood) calculations: Place the public officer/employee for whom you need to establish relationship by consanguinity in the blank box. The labeled boxes will then list the relationships by title to the public officer/employee. Anyone in a box numbered 1, 2, or 3 is within the third degree of consanguinity. Nevada Ethics in Government Law addresses consanguinity within third degree by blood, adoption or marriage. For Affinity (relationship by marriage) calculations: Place the spouse of the public officer/employee for whom you need to establish relationship by affinity in the blank box. The labeled boxes will then list the relationships by title to the spouse and the degree of distance from the public officer/employee by affinity. A husband and wife are related in the first degree by marriage. -

Documents, Part VIII

Sec. viIi CONTENTS vIiI–1 PART VIII. GLOSSATORS: MARRIAGE CONTENTS A. GRATIAN OF BOLOGNA, CONCORDANCE OF DISCORDANT CANONS, C.27 q.2 .............VIII–2 B. PETER LOMBARD, FOUR BOOKS OF SENTENCES, 4.26–7 ...................................................VIII–12 C. DECRETALS OF ALEXANDER III (1159–1181) AND INNOCENT III (1198–1216) 1B. Veniens ... (before 1170), ItPont 3:404 .....................................................................................VIII–16 2. Sicut romana (1173 or 1174), 1 Comp. 4.4.5(7) ..........................................................................VIII–16 3. Ex litteris (1175 X 1181), X 4.16.2..............................................................................................VIII–16 4. Licet praeter solitum (1169 X 1179, probably 1176 or1177), X 4.4.3.........................................VIII–17 5. Significasti (1159 X 1181), 1 Comp. 4.4.6(8)..............................................................................VIII–18 6 . Sollicitudini (1166 X 1181), 1 Comp. 4.5.4(6) ............................................................................VIII–19 7 . Veniens ad nos (1176 X 1181), X 4.1.15 .....................................................................................VIII–19 8m. Tuas dutu (1200) .......................................................................................................................VIII–19 9 . Quod nobis (1170 or 1171), X 4.3.1 ............................................................................................VIII–19 10 . Tuae nobis