Thesissatidpornwichundaphd2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thailand's Red Networks: from Street Forces to Eminent Civil Society

Southeast Asian Studies at the University of Freiburg (Germany) Occasional Paper Series www.southeastasianstudies.uni-freiburg.de Occasional Paper N° 14 (April 2013) Thailand’s Red Networks: From Street Forces to Eminent Civil Society Coalitions Pavin Chachavalpongpun (Kyoto University) Pavin Chachavalpongpun (Kyoto University)* Series Editors Jürgen Rüland, Judith Schlehe, Günther Schulze, Sabine Dabringhaus, Stefan Seitz The emergence of the red shirt coalitions was a result of the development in Thai politics during the past decades. They are the first real mass movement that Thailand has ever produced due to their approach of directly involving the grassroots population while campaigning for a larger political space for the underclass at a national level, thus being projected as a potential danger to the old power structure. The prolonged protests of the red shirt movement has exceeded all expectations and defied all the expressions of contempt against them by the Thai urban elite. This paper argues that the modern Thai political system is best viewed as a place dominated by the elite who were never radically threatened ‘from below’ and that the red shirt movement has been a challenge from bottom-up. Following this argument, it seeks to codify the transforming dynamism of a complicated set of political processes and actors in Thailand, while investigating the rise of the red shirt movement as a catalyst in such transformation. Thailand, Red shirts, Civil Society Organizations, Thaksin Shinawatra, Network Monarchy, United Front for Democracy against Dictatorship, Lèse-majesté Law Please do not quote or cite without permission of the author. Comments are very welcome. Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to the author in the first instance. -

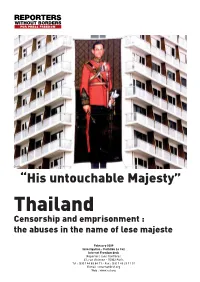

Thailand Censorship and Emprisonment : the Abuses in the Name of Lese Majeste

© AFP “His untouchable Majesty” Thailand Censorship and emprisonment : the abuses in the name of lese majeste February 2009 Investigation : Clothilde Le Coz Internet Freedom desk Reporters sans frontières 47, rue Vivienne - 75002 Paris Tel : (33) 1 44 83 84 71 - Fax : (33) 1 45 23 11 51 E-mail : [email protected] Web : www.rsf.org “But there has never been anyone telling me "approve" because the King speaks well and speaks correctly. Actually I must also be criticised. I am not afraid if the criticism concerns what I do wrong, because then I know. Because if you say the King cannot be criticised, it means that the King is not human.”. Rama IX, king of Thailand, 5 december 2005 Thailand : majeste and emprisonment : the abuses in name of lese Censorship 1 It is undeniable that King Bhumibol According to Reporters Without Adulyadej, who has been on the throne Borders, a reform of the laws on the since 5 May 1950, enjoys huge popularity crime of lese majeste could only come in Thailand. The kingdom is a constitutio- from the palace. That is why our organisa- nal monarchy that assigns him the role of tion is addressing itself directly to the head of state and protector of religion. sovereign to ask him to find a solution to Crowned under the dynastic name of this crisis that is threatening freedom of Rama IX, Bhumibol Adulyadej, born in expression in the kingdom. 1927, studied in Switzerland and has also shown great interest in his country's With a king aged 81, the issues of his suc- agricultural and economic development. -

University Life

English Newsletter by Komaba Students https://www.komabatimes.com/ Content University Life …………………… page 1 Perspectives …………………… page 12 Exploring Japan ………………… page 20 Komaba Writers’ Studio x Pensado … page 24 Creative Komaba ……………… page 29 27 Articles // April 2020 // Issue 9 UNIVERSITY LIFE The Good, the Bad, and PEAK: How I Discovered the Secret to University Life Through Movie Magic By: Paul Namkoong There wasn’t a single moment when I that the originals became unrecognizable, was - didn’t think about it. all the more appealing: tracted to movies because of how different the method of production was. Everything in my life had led up to this opportu- Spending 50 hours on creating a tiny, 3-minute nity. I followed what I saw on TV and the news. advertisement for our fledgling PEAK program From the short experience I’ve had working on I picked out the targets, staked them out, and turned out to be one of the most life-changing set, I remember getting hypnotized by the team- planned out all of the enthralling details. It didn’t experiences I’ve ever had. work and organization of each individual contrib- come easy, to play god over whom I took and utor. I once saw them as nobodies, mere scroll- whom I spared. But I fell in love with the power it Film is murder, and I am its (terrible) executioner. ing words upon scrolling words in an endless gifted me. I closed my eyes and envisioned what stream of movie credits. But when I saw the key would slip out of their lips, the unnatural move- I like shooting movies. -

(Title of the Thesis)*

University of Huddersfield Repository Treewai, Pichet Political Economy of Media Development and Management of the Media in Bangkok Original Citation Treewai, Pichet (2015) Political Economy of Media Development and Management of the Media in Bangkok. Doctoral thesis, University of Huddersfield. This version is available at http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/id/eprint/26449/ The University Repository is a digital collection of the research output of the University, available on Open Access. Copyright and Moral Rights for the items on this site are retained by the individual author and/or other copyright owners. Users may access full items free of charge; copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided: • The authors, title and full bibliographic details is credited in any copy; • A hyperlink and/or URL is included for the original metadata page; and • The content is not changed in any way. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/ POLITICAL ECONOMY OF MEDIA DEVELOPMENT AND MANAGEMENT OF THE MEDIA IN BANGKOK PICHET TREEWAI A thesis submitted to the University of Huddersfield in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Strategy, Marketing and Economics The University of Huddersfield March 2015 Abstract This study is important due to the crucial role of media in the dissemination of information, especially in emerging economies, such as Thailand. -

Working Paper 1

Working Paper 1 Armed Forces, the State, and Society Series AUTHORITARIAN POLICING AND DEMOCRATIZATION: THE CASE OF THAILAND EUGÉNIE MÉRIEAU Abstract: In this paper, I argue that the post-1970s democratization in Thailand had minimal effects on the entrenched practices of authoritarian policing. Democratization, in fact, did not put an end to these practices but instead correlated with their legalization through the enactment of a set of empowering legislation. This empirical finding invites a reconsid- eration of the hypothesis of covariation between regime type and policing practices. The NYU SCHOOL OF PROFESSIONAL STUDIES CENTER FOR GLOBAL AFFAIRS facilitates change by educating and inspiring our community to become global citizens capable of identifying and im- plementing solutions to pressing global challenges. We believe that the development of solu- tions to global problems must be informed by an understanding that the world’s challenges are not merely challenges for and among states, but among states and non-state actors; urban and rural communities; regional organizations as well as traditional diplomatic outlets. Through rig- orous graduate and non-degree programs and public events we prepare global citizens who will be at home – and thus be effective agents of change – in all of these environments. This working paper does represent the views of NYU, its staff, or faculty. ©The Author 2020 EUGÉNIE MÉRIEAU is a Postdoctoral Fellow at the Centre for Asian Legal Studies, National University of Singapore. She previously held positions at Sciences Po (France), Göttingen University (Germany) and Thammasat University (Thailand) and worked as a consultant for the International Commission of Jurists. -

A Comparative Study of Product Placement in Movies in the United States and Thailand

California State University, San Bernardino CSUSB ScholarWorks Theses Digitization Project John M. Pfau Library 2007 A comparative study of product placement in movies in the United States and Thailand Woraphat Banchuen Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project Part of the International Business Commons, and the Marketing Commons Recommended Citation Banchuen, Woraphat, "A comparative study of product placement in movies in the United States and Thailand" (2007). Theses Digitization Project. 3265. https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project/3265 This Project is brought to you for free and open access by the John M. Pfau Library at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses Digitization Project by an authorized administrator of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF PRODUCT PLACEMENT IN MOVIES IN THE UNITED STATES AND THAILAND A Project Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Business Administration by Woraphat Banchuen June 2007 A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF PRODUCT PLACEMENT IN MOVIES IN THE UNITED STATES AND THAILAND A Project Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino by Woraphat Banchuen June 2007 Victoria Seitz, Committee Chair, Marketing ( Dr. Nabil Razzouk © 2007 Woraphat Banchuen ABSTRACT Product placement in movies is currently very popular in U.S. and Thai movies. Many companies attempted to negotiate with filmmakers so as to allow their products to be placed in their movies. Hence, the purpose of this study was to gain more understanding of how the products were placed in movies in the United States and Thailand. -

Interview with Thanathorn Juangroongruangkit Kong Tsung

Interview with Tanathorn Juangroongruangkit NOVEMBER 2019–JANUARY 2020 VOLUME 5, NUMBER 1 Kong Tsung-gan • Richard Heydarian • Antony Dapiran 32 9 772016 012803 VOLUME 5, NUMBER 1 NOVEMBER 2019–JANUARY 2020 HONG KONG 3 Kong Tsung-gan Unwavering CHINA 5 Richard Heydarian Red Flags: Why Xi’s China Is in Jeopardy by George Magnus JOURNAL 7 Sunisa Manning Superstition INTERVIEW 9 Mutita Chuachang Tanathorn Juangroongruangkit NOTEBOOK 12 Faisal Tehrani Cursed CLIMATE 13 Jef Sparrow Losing Earth: Te Decade We Could Have Stopped Climate Change by Nathaniel Rich; Tis Is Not a Drill: An Extinction Rebellion Handbook by Clare Farrell, Alison Green, Sam Knights and William Skeaping (eds) ANTHROPOLOGY 14 Michael Vatikiotis Te Lisu: Far from the Ruler by Michele Zack ASIAN LIBRARY 15 Sean Gleeson Cambodia 1975–1982 by Michael Vickery DIARY 17 Antony Dapiran Hong Kong burning SOCIETY 22 Joe Freeman McMindfulness: How Mindfulness Became the New Capitalist Spirituality by Ronald E. Purser BORNEO 23 James Weitz Te Last Wild Men of Borneo: A True Story of Death and Treasure by Carl Hofman SHORT STORY 24 Andrew Lam “Dear TC” POEMS Rory Harris “frayed”, “shoes” ESSAYS 25 Paul Arthur un\\martyred: [self-]vanishing presences in Vietnamese poetry by Nha Tuyen POETRY 26 Robert Yeo “Small town romance” SINGAPORE 27 Teophilus Kwek On the fence NEIGHBOURHOOD 29 Fahmi Mustafa George Town PROFILE 30 Abby Seif Wilfred Chan TRIBUTE 32 Greg Earl B.J. Habibie FILM 33 Alexander Wells Danger Close: Te Battle of Long Tan THE BOOKSELLER 34 Lok Man Law Albert Wan mekongreview.com -

(Title of the Thesis)*

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Huddersfield Repository University of Huddersfield Repository Treewai, Pichet Political Economy of Media Development and Management of the Media in Bangkok Original Citation Treewai, Pichet (2015) Political Economy of Media Development and Management of the Media in Bangkok. Doctoral thesis, University of Huddersfield. This version is available at http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/26449/ The University Repository is a digital collection of the research output of the University, available on Open Access. Copyright and Moral Rights for the items on this site are retained by the individual author and/or other copyright owners. Users may access full items free of charge; copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided: • The authors, title and full bibliographic details is credited in any copy; • A hyperlink and/or URL is included for the original metadata page; and • The content is not changed in any way. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/ POLITICAL ECONOMY OF MEDIA DEVELOPMENT AND MANAGEMENT OF THE MEDIA IN BANGKOK PICHET TREEWAI A thesis submitted to the University of Huddersfield in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Strategy, Marketing and Economics The University of Huddersfield March 2015 Abstract This study is important due to the crucial role of media in the dissemination of information, especially in emerging economies, such as Thailand. -

FULLTEXT01.Pdf

Essential reading for anyone interested in ai politics and culture e ai monarchy today is usually presented as both guardian of tradition and the institution to bring modernity and progress to the ai people. It is moreover Saying the seen as protector of the nation. Scrutinizing that image, this volume reviews the fascinating history of the modern monarchy. It also analyses important cultural, historical, political, religious, and legal forces shaping Saying the Unsayable Unsayable the popular image of the monarchy and, in particular, of King Bhumibol Adulyadej. us, the book o ers valuable Monarchy and Democracy insights into the relationships between monarchy, religion and democracy in ailand – topics that, a er the in Thailand September 2006 coup d’état, gained renewed national and international interest. Addressing such contentious issues as ai-style democracy, lése majesté legislation, religious symbolism and politics, monarchical traditions, and the royal su ciency economy, the book will be of interest to a Edited by broad readership, also outside academia. Søren Ivarsson and Lotte Isager www.niaspress.dk Unsayable-pbk_cover.indd 1 25/06/2010 11:21 Saying the UnSayable Ivarsson_Prels_new.indd 1 30/06/2010 14:07 NORDIC INSTITUTE OF ASIAN STUDIES NIAS STUDIES IN ASIAN TOPICS 32 Contesting Visions of the Lao Past Christopher Goscha and Søren Ivarsson (eds) 33 Reaching for the Dream Melanie Beresford and Tran Ngoc Angie (eds) 34 Mongols from Country to City Ole Bruun and Li Naragoa (eds) 35 Four Masters of Chinese Storytelling -

Puangchon Unchanam ([email protected])

THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK GRADUATE SCHOOL AND UNIVERSITY CENTER Ph.D. Program in Political Science Student’s Name: Puangchon Unchanam ([email protected]) Dissertation Title: The Bourgeois Crown: Monarchy and Capitalism in Thailand, 1985-2014 Banner ID Number: 0000097211 Sponsor: Professor Corey Robin ([email protected]) Readers: Professor Susan Buck-Morss ([email protected]) Professor Vincent Boudreau ([email protected]) Abstract Most scholars believe that monarchy is irrelevant to capitalism. Once capitalism becomes a dominant mode of production in a state, the argument goes, monarchy is either abolished by the bourgeoisie or transformed into a constitutional monarchy, a symbolic institution that plays no role in the economic and political realms, which are exclusively reserved for the bourgeoisie. The monarchy of Thailand, however, fits neither of those two narratives. Under Thai capitalism, the Crown not only survives but also thrives politically and economically. What explains the political hegemony and economic success of the Thai monarchy? Examining the relationship between the transformation of the Thai monarchy’s public images in the mass media and the history of Thai capitalism, this study argues that the Crown has become a “bourgeois monarchy.” Embodying both royal glamour and middle-class ethics, the “bourgeois monarchy” in Thailand has been able to play an active role in the national economy and politics while secretly accumulating wealth because it provides a dualistic ideology that complements the historical development of Thai capitalism, an ideology that not only motivates the Thai bourgeoisie to work during times of economic growth but also tames bourgeois anxiety when economic crisis hits the country. -

298744 Karin Zackari

Framing the Subjects Human Rights and Photography in Contemporary Thai History Hongsaton Zackari, Karin 2020 Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Hongsaton Zackari, K. (2020). Framing the Subjects: Human Rights and Photography in Contemporary Thai History. (1 ed.). MediaTryck Lund. Total number of authors: 1 General rights Unless other specific re-use rights are stated the following general rights apply: Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal Read more about Creative commons licenses: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. LUND UNIVERSITY PO Box 117 221 00 Lund +46 46-222 00 00 Framing the Subjects Human Rights and Photography in Contemporary Thai History KARIN ZACKARI JOINT FACULTIES OF HUMANITIES AND THEOLOGY | LUND UNIVERSITY Joint Faculties of Humanities and Theology 213166 Department of History Human Rights Studies 789189 ISBN 978-91-89213-16-6 9 Framing the Subjects Human Rights and Photography in Contemporary Thai History Karin Zackari DOCTORAL DISSERTATION with due permission of the Joint Faculties of Humanities and Theology, Lund University, Sweden. -

Supachalasai Chyatat

Theorising the Politics of Survivors: Memory, Trauma, and Subjectivity in International Politics Chyatat Supachalasai Thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Ph.D. Department of International Politics Aberystwyth University June 2017 DECLARATION This work has not previously been accepted in substance for any degree and is not being concurrently submitted in candidature for any degree. Signed……………………………………………. (candidate) Date……………………………………………13/7/2017 …. STATEMENT 1 This thesis is the result of my own investigations, except where otherwise stated. Other sources are acknowledged by footnotes giving explicit references. A bibliography is appended. Signed……………………………………………. (candidate) Date……………………………………………….13/7/2017 STATEMENT 2 I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter- library loan, and for the title and summary to be made available to outside organisations. Signed……………………………………………. (candidate) Date……………………………………………….13/7/2017 i Summary This thesis aims to develop a theory of the politics of survivors based on the interrelated issues of memory, trauma, and subjectivity. It defines survivors as those who psychologically suffered from a traumatic event and whose mentalities continue to be affected by traumas. This thesis understands survivors as active participants in political resistance aimed at overthrowing current, authoritarian governments. In order to develop an appropriate theory of the politics of survivors, this thesis examines literature across the disciplines of social science. First, it adopts memory literature to argue that the political crises survivors have endured lead to the development of collective memory among survivors. Second, it incorporates literature of trauma to demonstrate that trauma cannot be conveyed in its entirety in testimony or language.