Sitelines Spring 2012

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cornelia Hahn Oberlander Reflections

The Cultural Landscape Foundation Pioneers of American Landscape Design ___________________________________ CORNELIA HAHN OBERLANDER ORAL HISTORY REFLECTIONS ___________________________________ Nina Antonetti Susan Ng Chung Allegra Churchill Susan Cohen Cheryl Cooper Phyllis Lambert Eva Matsuzaki Gino Pin Sandy Rotman Moshe Safdie Bing Thom Shavaun Towers Hank White Elisabeth Whitelaw © 2011 The Cultural Landscape Foundation, all rights reserved. May not be used or reproduced without permission. Scholar`s Choice: Cornelia Hahn Oberlander-From Exegesis to Green Roof by Nina Antonetti Assistant Professor, Landscape Studies, Smith College 2009 Canadian Center for Architecture Collection Support Grant Recipient, December 2009 March 2011 What do a biblical garden and a green roof have in common? The beginning of an answer is scrawled across the back of five bank deposit slips in the archives of Cornelia Hahn Oberlander at the CCA. These modest slips of paper, which contain intriguing exegesis and landscape iconography, are the raw material for a nineteen-page document Oberlander faxed to her collaborator Moshe Safdie when answering the broad programming requirements of Library Square, the Vancouver Public Library and its landscape. For the commercial space of the library, Oberlander considered the Hanging Gardens of Babylon and the hanging gardens at Isola Bella, Lago Maggiore; for the plaza, the civic spaces of ancient Egypt and Greece; and for the roof, the walled, geometric gardens of the Middle Ages and Early Renaissance. Linking book to landscape, she illustrated the discovery of the tree of myrrh during the expedition of Hatshepsut, referenced the role of plants in Genesis and Shakespeare, and quoted a poem by environmental orator Chief Seattle. -

Richard Haag Reflections

The Cultural Landscape Foundation Pioneers of American Landscape Design ___________________________________ RICHARD HAAG ORAL HISTORY REFLECTIONS ___________________________________ Charles Anderson Lucia Pirzio-Biroli/ Michele Marquardi Luca Maria Francesco Fabris Falken Forshaw Gary R. Hilderbrand Jeffrey Hou Linda Jewell Grant Jones Douglas Kelbaugh Reuben Rainey Nancy D. Rottle Allan W. Shearer Peter Steinbrueck Michael Van Valkenburgh Thaisa Way © 2014 The Cultural Landscape Foundation, all rights reserved. May not be used or reproduced without permission. Reflections of Richard Haag by Charles Anderson May 2014 I first worked with Rich in the 1990's. I heard a ton of amazing stories during that time and we worked on several great projects but he didn't see the need for me to use a computer. That was the reason I left his office. Years later he invited me to work with him on the 2008 Beijing Olympic competition. In the design charrettes he and I did numerous drawings but I did much of my work on a tablet computer. In consequent years we met for lunch and I showed him my projects on an iPad. For the first time I saw a glint in his eye towards that profane technology. I arranged for an iPad to arrive in his office on Christmas Eve in 2012. Cheryl, his wife, made sure Rich was in the office that day to receive it. His name was engraved on it along with the quote, "The cosmos is an experiment", a phrase he authored while I worked for him. He called © 2014 The Cultural Landscape Foundation, all rights reserved. May not be used or reproduced without permission. -

2 People Downtown

U U. 2 people downtown 2.1 FAMILIES AND CHILDREN McAfee: Looking at this particular area in the down Oberlander: This could be a chance to town, I tend to think it is a somewhat romantic notion recognize Mr. Moir who has been very patiently waiting--member of the Vancouver to expect large numbers of families with children, School Board. You are certainly a part of a network which goes well beyond the down particularly with school-age youngsters, to be able to town and to some degree the stitching relates to whatever the School Board is up afford to choose this area over other parts of the city. to. Moir: Mr. Chairman, I just couldn’t help If I was looking at family housing policy, I don’t think noticing that in these three very excellent presentations, there is no mention of the that I need to have a child on every block in the city. children, particularly as we come from a system that has lost over 2,100 students a I would rather see the rest of the city be the areas year for over ten years. We’re continuing to decline, at a rate of 1,800 to 1,900 that we focus families in, and that even if we’re students a year, and my question is, “How important are the children to the talking about the ‘single-mother’ on social assistance population mix in the urban core?” “Are they important, and if so what should be or very modest income, requiring quite heavy government done to ensure that this happens in the redevelopment?” subsidies, we would probably be better to look for smaller scattered housing sites, in areas that are already schooled, rather than trying to put a few token youngsters in this area, and then see the problems of having to equip ferry systems across False Creek in order to get to schools on the south shore; or have the six- or eight-year o!ds trotting along down Denman Street and Davie Street into the West End in order to get to the existing schools. -

National Register of Historic Places Continuation Sheet Condominium 1 Sonoma County, California Section Number 7 Page 1

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 (Oct. 1990) H"^l United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. 1. Name of Property________________________________________________________ historic name Condominium 1 ________________________________________________________ other names/site number __________________________________ 2. Location street & number 110-128 Sea Walk Drive_____________ NA I I not for publication city or town The Sea Ranch_________________ ___NA[~1 vicinity state California_______ code CA county Sonoma. code 097_ zip code 95497 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1986, as amended, i hereby certify that this ^ nomination D request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property ^ meets D does not meet the National Register Criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant 03 nationally D statewide D locally. -

J&J History Book.Indd

Like Darwin’s F inches The Story of Jones & Jones By Anne Elizabeth Powell A PROPOSAL About the Book ike Darwin’s Finches: The Story of Jones & Jones extinct had they lived on the same island. What we is the fi rst comprehensive examination of the have always done is handicap ourselves at the outset by L singular practice of Seattle-based Jones & Jones, saying, ‘Let’s go where it’s harder—where the answers the fi rm established in 1969 by Grant Jones and haven’t been found yet.’ ” Ilze Grinbergs Jones to practice landscape architecture, architecture, environmental planning, and urban design But just as signifi cant as the Jones & Jones approach is as a fully integrated collaborative. What defi nes this the Jones & Jones perspective. Through the lenses of practice as “singular?” In the words of Grant Jones, these practitioners the earth is held in sharp focus as “I think what sets us apart is not the projects—not the a living organism—alive, the product of natural forms work—but the idea that you can grow and evolve and and processes at work. The earth is their client, and their survive by tackling the diffi cult and the impossible. designs place nature fi rst, seek to discern the heart and You don’t look for the commonplace; you don’t look for soul of the land—to fi nd the signature in each landscape— the safe place to ply your craft. Jones & Jones is sort of like and to celebrate this intrinsic beauty. Darwin’s fi nches in that we’ve always been looking for ways to crack a nut that no one else has been able to crack. -

Bloedel Reserve | February 2012

RICHARD HAAG | BLOEDEL RESERVE | FEBRUARY 2012 Bibliography (partial) Ament, Deloris Tarzan. “The Great Escape: Bainbridge Island’s Bloedel Reserve Offers a Tranquil, Green Retreat to Soothe the Spirit.” Seattle Times (9 October 1988) K1, K5. American Academy in Rome, “Annual Exhibition 1998,” June 12-July 12, 1998 (exhibition catalog), 52-55, 106. Appleton, Jay. The Experience of Landscape. Rev. ed. London: John Wiley and Sons, 1996: 248, 250, 254. Arbor Fund, Foundation. Bloedel Reserve. 2010. http://www.bloedelreserve. Beason, Tyrone. “Paul Hayden Kirk Left His Mark On Architecture Of Northwest.” The Seattle Times, May 25, 1995. “Bloedel Reserve: Jury Comments,” [ASLA President’s Award of Design Excellence] (Architectural League of New York’s Inhabited Landscapes exhibition), Places 4:4 (1987): 14-15. Botta, Marina. “Seattle: 140 Acres of Green Rooms.” Abitare (Italy) 272 (March 1989): 219-23. Fabris, Luca M.F. La Natura Come Amante/Nature as a Lover. Maggioli S.p.A. 2010: 7, 9, 13, 70-93. Frankel, Felice (photographs) and Jory Johnson (text). “The Bloedel Reserve.” Modern Landscape Architecture: Redefining the Garden. New York: Abbeville Press, 1991, 52- 69. Frey, Susan Rademacher, “A Series of Gardens,” Landscape Architecture Magazine (September 1986): cover, 55-61, 128. [ASLA President’s Award of Design Excellence coverage and site impressions.] Haag, Richard. “Contemplations of Japanese Influence on the Bloedel Reserve.” Washington Park Arboretum Bulletin 53:2 (Summer 1990): 16-19. Haddad, Laura. “Richard Haag: Bloedel Reserve and Gas Works Park.” Book Review. Arcade, 16.3 (Spring 1998) 34. Illman, Deborah. 1998 UW Showcase: Arts and Humanities at the University of Washington. -

Landmark NOMINATION Application Name: Year Built: 1965-67 (Phase O

Landmark NOMINATION Application Name: Year Built: 1965-67 (Phase One); 1970-71 (Phase Two) (Common, present or historic) Historic – Battelle Memorial Institute Seattle Research Center Present – Talaris Conference Center Street and Number: 4000 NE 41st Street, Seattle, Washington 98105 Assessor’s File No. 1525049010 ________________________________ Legal Description: See attached _________________________________ Plat Name: Town of Yesler Block: n/a Lot: Government Lot 2 Present Owner: 4000 Property, LLC. Present Use: Conference Center Address: 4000 NE 41st Street , Seattle, WA 98105 __________________ Original Owner: Battelle Memorial Institute (BMI) ___________________ Original Use: Research/Institutional Campus __________________________ Architect: NBBJ, Inc.; Rich Haag Associates, Landscape Architect _____ Builder: Farwest Construction Company Description: Present and original (if known) physical appearance and characteristics See attached Landmark Nomination Report Statement of significance: See attached Landmark Nomination Report Photographs: See attached Landmark Nomination Report for graphics—maps, plans and photographs Submitted by: Friends of Battelle/Talaris, contact: Janice Sutter Phone 206.683.9280 Address 4616 25th Ave NE, #146, Seattle, WA 98105 Date March 28, 2013 (revised August 5, 2013) Reviewed Date Historic Preservation Officer Legal Description for Battelle Memorial Institute/Talaris (attachment to Landmark Nomination Application Form) That portion of Government Lot 2 and of the Northeast Quarter of the Northwest Quarter -

Bibliography and Chronology of Regional Planning in British Columbia

BIBLIOGRAPHY AND CHRONOLOGY OF REGIONAL PLANNING IN BRITISH COLUMBIA PREPARED BY FRANCES CHRISTOPHERSON PUBLISHED WITH THE ASSISTANCE OF THE MINISTRY OF MUNICIPAL AFFAIRS DISTRIBUTED BY THE UNION OF BC MUNICIPALITIES AND THE PLANNING INSTITUTE OF BC FIFTY YEARS OF REGIONAL PLANNING IN BRITISH COLUMBIA CELEBRATING THE PAST ANTICIPATING THE FUTURE EXECUTIVE December 2000 Linda Allen Diana Butler Ken Cameron This bibiography and cronology were commissioned to celebrate Joan Chess 50 years of Regional Planning in British Columbia. Nancy Chiavario Neil Connelly Frances Christopherson, retired GVRD Librarian, generously John Curry Gerard Farry offered to author this work on a voluntary basis. Marino Piombini, George Ferguson Senior Planner, Greater Vancouver Regional District provided Harry Harker great assistance. Don Harasym Blake Hudema Others whose assistance is gratefully acknowledge include Erik Karlsen W.T. Lane Annette Dignan, and Chris Plagnol of the GVRD, Karoly Krajczar Darlene Marzari of Translink, and Peggy McBride of the UBC Fine Arts Library, Joanne Monaghan H.P. Oberiander Funds for publication were provided by the Minister of Tony Pan- Municipal Affairs. The Union of BC Municipalities assisted Garry Runka Jay Simons in the distribution. Additional copies may be obtained from Hilda Symonds UBCM or the or the Planning Institute of BC. Peter Tassie Richard Taylor I wish to thank the executive for their enthusiastic participation Tony Roberts in our activities and in particular Gerard Farry for facilitating this Brahm Wiesman publication. Brahm Wiesman Chairman FIFTY YEARS OF REGIONAL PLANNING IN BRITISH COLUMBIA CELEBRATING THE PAST, ANTICIPATING THE FUTURE: PART I BIBLIOGRAPHY PART II CHRONOLOGY Entries are arranged by publication date, then by corporate or individual author. -

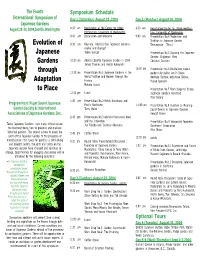

Evolution of Japanese Gardens Through Adaptation to Place

The Fourth Symposium Schedule International Symposium of Day 1.(Saturday) August 28 ,2004 Day 3.(Monday) August 30 ,2004 Japanese Gardens August 28-30, 2004,Seattle, Washington 8:30 am Registration at the Center for Urban 8:30 am Registration:Center for Urban Horticul- Horticulture, University of Washington ture, University of Washington 9:00 am Declaration and Welcome 9:00 am Presentation No.4 Modernism and Tradition in Japanese Garden Evolution of 9:30 am Keynote Address:Can Japanese Gardens Tatsunosuke Tatsui evolve and change? Japanese Takeo Uesugi Presentation No.5 Evolving the Japanese Garden: Shigemori Mirei 10:30 am Address:Seattle Japanese Garden in 2004 Christian Tschumi Gardens James Thomas and Koichi Kobayashi 10:00 am Presentation No.6 Revitalized classic through 11:15 am Presentation No.1:Japanese Gardens in the gardens for public use in Tokyo World:Tradition and Modern through the Noritaka Tashiro, Katsutoyo Shiina, Adaptation History Masao Igarashi Makoto Suzuki to Place Presentation No.7 From Daigo to Ithaca: 12:15 pm Lunch Japanese Gardens Revisited Marc Keane 1:45 pm Presentation No.2:Welch Sanctuary and Program Host: Puget Sound Japanese Pacific Northwest 11:00 am Presentation No.8 Function as Meaning- Garden Society & International Terry Welch Social Events in Japanese Gardens Associations of Japanese Gardens, Inc. Kendall Brown 2:45 pm Presentation No.3:World . of Kuniyoshi Araki and His Innovation Presentation No.9 Vancouver Japanese Today Japanese Gardens face many critical issues: Jun Takeda and Tsutomu Akamatsu -

The Sea Ranch Soundings

THE SEA RANCH ASSOCIATION PRSRT STD P.O. BOX 16 U.S. POSTAGE PAID MEDFORD, OR THE SEA RANCH, CA 95497-0016 PERMIT NO. 125 Address Service Requested A QUARTERLY NEWSPAPER WRITTEN BY AND FOR THE SEA RANCH ASSOCIATION MEMBERS NUMBER 122 FALL 2014 IN THIS ISSUE: Sea Ranch Celebrates Volunteers; Community NORTH COAST MUSIC NIGHT Spirit Award Presented to Jim DeWilder Around 120 Sea Ranchers gathered at SEAL DOCENT UPDATE One-Eyed Jacks on August 31 to share good food and drink and celebrate volunteerism on the coast. Commu- NOBEL PRIZE WINNER nity Manager Frank Bell welcomed the group for the seventh annual picnic and read a long list of folks who have joined the ranks of volunteers for committees, SEA RANCH HISTORY task forces and other organizations, both on and off The Sea Ranch, since last year’s event. The afternoon was also the occasion for the presentation of the TSRVFD Considers Rosemarie Hocker Community Spirit Forming Fire Award. The award was first presented in 2011 Protection District and was developed by the Communica- by Bonnie Plakos, President, and Don McMahan, tion Committee and established by the Vice President, TSR Volunteer Fire Department Community Manager. lt is named in Board honor of former Board Member Rose- marie Hocker, who passed away that Many Sea Ranchers have had to call year. In leadership roles and in her vol- 9-1-1 and have been relieved to see big unteer work behind the scenes, Rosema- red trucks and friendly faces at the door rie, by encouragement and example, ex- in a very short time (day or night, rain emplified what is meant by Community or shine). -

Complete Teachers' Guide to Enemy

“EnemyAliens” The Internment of Jewish Refugees in Canada, 1940-1943 TEACHER’S GUIDE “ENEMY ALIENS”: The Internment of Jewish Refugees in Canada, 1940-1943 © 2012, Vancouver Holocaust Education Centre Lessons: Nina Krieger Text: Paula Draper Research: Katie Powell, Katie Renaud, Laura Mehes Translation: Myriam Fontaine Design: Kazuko Kusumoto Copy Editing: Rome Fox, Anna Migicovsky Cover image: Photograph of an internee in a camp uniform, taken by internee Marcell Seidler, Camp N (Sherbrooke, Quebec), 1940-1942. Seidler secretly documented camp life using a handmade pinhole camera. − Courtesy Eric Koch / Library and Archives Canada / PA-143492 Vancouver Holocaust Education Centre 50 - 950 West 41st Avenue Vancouver, BC V5Z 2N7 604 264 0499 / [email protected] / www.vhec.org Material may be reproduced for non-commercial purposes provided that the publisher and author are acknowledged. The exhibit Enemy Aliens: The Internment of Jewish Refugees in Canada, 1940 – 1943 was generously funded by the Community Historical Recognition Program of the Department of Citizenship, Immigration and Multiculturalism Canada. With the generous support of: Oasis Foundation The Ben and Esther Dayson Charitable Foundation The Kahn Family Foundation Isaac and Sophie Waldman Endowment Fund of the Vancouver Foundation Frank Koller The Vancouver Holocaust Education Centre gratefully acknowledges the financial investment by the Department of Canadian Heritage in the creation of this online presentation for the Virtual Museum of Canada. Teacher’s Guide made possible through the generous support of the Mordehai and Hana Wosk Family Endowment Fund of the Vancouver Holocaust Centre Society. With special thanks to the former internees and their families, who generously shared their experiences and artefacts in the creation of the exhibit. -

LAKE UNION Historical WALKING TOUR

B HistoryLink.org Lake Union Walking Tour | Page 1 b Introduction: Lake Union the level of Lake Union. Two years later the waters of Salmon Bay were raised behind the his is a Cybertour of Seattle’s historic Chittenden Locks to the level of Lake Union. South Lake Union neighborhood, includ- Historical T As the Lake Washington Ship Canal’s ing the Cascade neighborhood and portions Walking tour Government Locks (now Hiram of the Denny Regrade. It was written Chittenden Locks) neared its 1917 and curated by Paula Becker with completion, the shores of Lake Union the assistance of Walt Crowley and sprouted dozens of boat yards. For Paul Dorpat. Map by Marie McCaffrey. most of the remaining years of the Preparation of this feature was under- twentieth century, Lake Union was written by Vulcan Inc., a Paul G. Allen one of the top wooden-boat building Company. This Cybertour begins at centers in the world, utilizing rot- Lake Union Park, then loosely follows resistant local Douglas fir for framing the course of the Westlake Streetcar, and Western Red Cedar for planking. with forays into the Cascade neighbor- During and after World War I, a hood and into the Seattle Center area. fleet of wooden vessels built locally for the war but never used was moored Seattle’s in the center of Lake Union. Before “Little Lake” completion of the George Washington ake Union is located just north of the Washington, Salmon Bay, and Puget Sound. Memorial Bridge (called Aurora Bridge) in L geographic center and downtown core A little more than six decades later, Mercer’s 1932, a number of tall-masted ships moored of the city of Seattle.