Acta Neophilologica

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Memorial Services

BATTLE OF CRETE COMMEMORATIONS ATHENS & CRETE, 12-21 MAY 2019 MEMORIAL SERVICES Sunday, 12 May 2019 10.45 – Commemorative service at the Athens Metropolitan Cathedral and wreath-laying at the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier at Syntagma Square Location: Mitropoleos Street - Syntagama Square, Athens Wednesday, 15 May 2019 08.00 – Flag hoisting at the Unknown Soldier Memorial by the 547 AM/TP Regiment Location: Square of the Unknown Soldier (Platia Agnostou Stratioti), Rethymno town Friday, 17 May 2019 11.00 – Commemorative service and wreath-laying at the Army Cadets Memorial Location: Kolymbari, Region of Chania 11.30 – Commemorative service and wreath-laying at the 110 Martyrs Memorial Location: Missiria, Region of Rethymno Saturday, 18 May 2019 10.00 – Commemorative service and wreath-laying at the Memorial to the Fallen Greeks Location: Latzimas, Rethymno Region 11.30 – Commemorative service and wreath-laying at the Australian-Greek Memorial Location: Stavromenos, Region of Rethymno 13.00 – Commemorative service and wreath-laying at the Greek-Australian Memorial | Presentation of RSL National awards to Cretan students Location: 38, Igoumenou Gavriil Str. (Efedron Axiomatikon Square), Rethymno town 18.00 – Commemorative service and wreath-laying at the Memorial to the Fallen Inhabitants Location: 1, Kanari Coast, Nea Chora harbour, Chania town 1 18.00 – Commemorative service and wreath-laying at the Memorial to the Fallen & the Bust of Colonel Stylianos Manioudakis Location: Armeni, Region of Rethymno 19.30 – Commemorative service and wreath-laying at the Peace Memorial for Greeks and Allies Location: Preveli, Region of Rethymno Sunday, 19 May 2019 10.00 – Official doxology Location: Presentation of Mary Metropolitan Church, Rethymno town 11.00 – Memorial service and wreath-laying at the Rethymno Gerndarmerie School Location: 29, N. -

Memorial Services

BATTLE OF CRETE COMMEMORATIONS CRETE, 15-21 MAY 2018 MEMORIAL SERVICES Tuesday, 15 May 2018 11.00 – Commemorative service at the Agia Memorial at the “Brigadier Raptopoulos” military camp Location: Agia, Region of Chania Wednesday, 16 May 2018 08.00 – Flag hoisting at the Unknown Soldier Memorial by the 547 AM/TP Regiment Location: Square of the Unknown Soldier (Platia Agnostou Stratioti), Rethymno town 18.30 – Commemorative service at the Memorial to the Fallen Residents of Nea Chora Location: 1, Kanaris Coast, Nea Chora harbour, Chania town Thursday, 17 May 2018 10.30 – Commemorative service at the Australian-Greek Memorial Location: Stavromenos, Region of Rethymno 11.00 – Commemorative service at the Army Cadets Memorial (followed by speeches at the Orthodox Academy of Crete) Location: Kolymvari, Region of Chania 12.00 – Commemorative service at the Greek-Australian Memorial Location: 38, Igoumenou Gavriil Str., Rethymno town 18.00 – Commemorative service at the Memorial to the Fallen & the Bust of Colonel Stylianos Manioudakis Location: Armeni, Region of Rethymno 19.30 – Commemorative service at the Peace Memorial in Preveli Location: Preveli, Region of Rethymno 1 Friday, 18 May 2018 10.00 – Flag hoisting at Firka Fortress Location: Harbour, Chania town 11.30 – Commemorative service at the 110 Martyrs Memorial Location: Missiria, Region of Rethymno 11.30 – Military marches by the Military Band of the 5th Infantry Brigade Location: Harbour, Chania town 13.00 – Commemorative service at the Battle of 42nd Street Memorial Location: Tsikalaria -

70 Xronia Program 2011.Indd

70 YEARS SINCE THE BATTLE OF CRETE ΠΡΟΓΡΑΜΜΑ ΕΚΔΗΛΩΣΕΩΝ PROGRAMME OF COMMEMORATIVE EVENTS ΠΡΟΓΡΑΜΜΑ ΕΚ∆ΗΛΩΣΕΩΝ PROGRAMME OF COMMEMORATIVE EVENTS ΠΕΡΙΦΕΡΕΙΑ ΚΡΗΤΗΣ – ΠΕΡΙΦΕΡΕΙΑΚΗ ΕΝΟΤΗΤΑ ΧΑΝΙΩΝ Γραφείο Τύπου & ∆ηµοσίων Σχέσεων Πλατεία Ελευθερίας 1, 73100 Χανιά Τηλ. 28213-40160 / Φαξ 28213-40222 E-mail: [email protected] REGION OF CRETE – REGIONAL UNIT OF CHANIA Press, Public & International Relations Office 1 Εleftherias Square, Chania 73100 Tel. 28213-40160 / Fax 28213-40222 E-mail: [email protected] Συντονισµός εκδηλώσεων: Σήφης Μαρκάκης, Υπεύθυνος Τύπου & ∆ηµοσίων Σχέσεων της Π.Ε. Χανίων Coordination of events: Iosif Markakis, Head of the Press, Public & International Rela- tions Office of the Regional Unit of Chania Επιµέλεια κειµένων: Αθανασία Ζώτου, Υπ/λος Π.Ε. Χανίων Text editing: Athanasia Zotou, Civil Servant, Regional Unit of Chania Μετάφραση: Ρούλα Οικονοµάκη, Υπ/λος Π.Ε. Χανίων Translation: Roula Ikonomakis, Civil Servant, Regional Unit of Chania ∆ηµιουργικό: Μάριος Γιαννιουδάκης Art work: Marios Giannioudakis 70 ΧΡΟΝΙΑ ΑΠΟ ΤΗΝ ΜΑΧΗ ΤΗΣ ΚΡΗΤΗΣ 70 YEARS SINCE THE BATTLEBATTLE OFOF CRETECRETE ΜΗΝΥΜΑ MESSAGE FROM ΤΟΥ ΠΡΩΘΥΠΟΥΡΓΟΥ ΤΗΣ ΕΛΛΑ∆ΑΣ G.A. PAPANDREOU, PRIME MINISTER OF GREECE ΓΙΩΡΓΟΥ Α. ΠΑΠΑΝ∆ΡΕΟΥ Today we pay tribute to the heroic fighters who sacrificed their lives with self- Αποτίουµε σήµερα φόρο τιµής στους ηρωικούς αγωνιστές της Μάχης της denial for the sake of our country by taking part in the Battle of Crete where Κρήτης, που µε αυτοθυσία και αυταπάρνηση έδωσαν την ζωή τους για την they defended the inalienable right of every people to freedom, independence, πατρίδα, προασπίζοντας το αναφαίρετο δικαίωµα κάθε λαού στην ελευθερία, την integrίty and decency. ανεξαρτησία, την αξιοπρέπεια. -

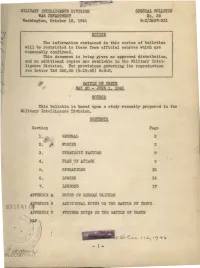

Oct 18 !41 Appendix C Further Notes on the Battle of Crete

MILITARY INTELLIG~~CE DIVISION SPECIAL BULLETIN W.AR DEPARTMENT No. 35 Washington. October 15, 1941 G-2/ 2657-231 NOTICE The information contained in this series of bulletins will be restricted to items from official sources which are . reasonably confirmed. This document is being given an approved distribution, and no additional copies are available in the Military Intel ligence Division. For provisions governing its reproduction see Letter TAG 350.05 (9-19-40) M-B-M. BATTLE OF CRETE MAY 20 - JUNE l, 1941 SOURCE This bulletin is based upon a stud~r recently prepe..red in the Military Intelligence Division. CONTENTS Section Page l. GENERAL 2 2. FORCES 3 r 3. STRAT~GIC FACTORS 8 4. PLAN OF ATTACK 9 5. OPERATIONS 10 6. LOSSES 16 ?. LESSONS 17 APPENDIX A NOTES ON GEPJ·IAN GLIDERS PENDIX B ADDITIONAL NOTES ON THE BATTLE OF CRETE OCT 18 !41 APPENDIX C FURTHER NOTES ON THE BATTLE OF CRETE - l- ·' . -- .- - _.,._·~-·: ·~;;; .... ·~ . ~;.; ,.,-, ··;. ::--·_ ~ . -- 13A'l'TLE OF CBET.E* MAY 20 - JUliE 1, 1941 1. G.ElmBAL The German conquest of Crete, effected bet\v-een Hay 20 and June 1, 1941, constitutes the first occasion in history \V"hen an ex peditionary force tr~~sported by air and e~ air fleet conquered a distant island protected by an overwhelmingly superior navy and a land garrison \IThich was considerably stronger, numerically, th~~ the invading force. Such an outcome would have been ~thinkable two years ago. Today, however, the result of that campaign a\ITakens among soldiers merely a mild feeling of surprise; the importance of air po\'ler has been brought home to the world since 1939. -

![Downloads/Article/838/Tavronitis%20Waterplan Sept2012.Pdf> [Accessed 03 December 2015]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8886/downloads-article-838-tavronitis-20waterplan-sept2012-pdf-accessed-03-december-2015-5328886.webp)

Downloads/Article/838/Tavronitis%20Waterplan Sept2012.Pdf> [Accessed 03 December 2015]

REPORT ON PROJECT’S TARGETED AREAS AND PILOT SUB-BASINS CHARACTERISTICS ACTION A1 LIFE14 CCA/GR/000389 - AgroClimaWater Promoting water efficiency and supporting the shift towards a climate resilient agriculture in Mediterranean countries Deliverable A1.2: Report on project’s targeted areas and pilot sub-basins characteristics Action A1: Identification of targeted project’s areas and selection of pilot sub-basins – Gaining local support in the targeted project’s areas Sub Action A1.1: Identification of targeted project’s areas and selection of pilot sub-basins – Collection of generic data Action: A1 (sub-action A1.1) Release: Final Version Action IOTSP Responsible: Contribution to HYETOS, UNIBAS, LRI, action’s RODAXAGRO, KEDHP, implementation: MIRABELLO, AFI JANUARY 2016 Project LIFE14 ENV/GR/000389–AgroClimaWater is implemented with the contribution of the LIFE Programme of the European Union and project’s partner scheme LIFE14 CCA/GR/000389 - AGROCLIMAWATER Blank on purpose REPORT ON PROJECT’S TARGETED AREAS AND PILOT SUB-BASINS CHARACTERISTICS ACTION A1 Terminology / Abbreviations Term Description 2D Two-dimensional AATO Authority of Optimum Territorial Ambit AFI Assofruit Italia Società Cooperativa Agricola AWMS Agricultural Water Management Strategy AWU Annual work unit BC Before christ C Celsius CBBM Consorzio di Bonifica di Bradano e Metaponto CCDA Common Database on Designated Areas d Day DEYA Municipal Water & Sewage Company DEYAAN Municipal Enterprise of Agios Nikolaos DEYABA Inter municipal Water & Sewage Company of the Northern Coast of the Prefecture of Chania (Diamimotiki Epihirisi Ydrefsis Apohetefsis Voriou Axona) E East Elev Elevation ELSTAT Hellenic Statistical Authority EU European Union Fig. Figure GDP Gross Domestic Product GPV Gross Production Value GR Greece GVA Gross Value Added ha Hectare HCV areas High Conservation Value areas hr Hour i.e. -

The Battle of Crete: Nazi's Elite War-Machine Stopped Largely By

The Battle of Crete: Nazi’s Elite War-Machine Stopped Largely by Crete’s Non-Combatant Population by: Manolis Velivasakis, President Pancretan Association of America. Good afternoon Ladies and Gentlemen, I am very pleased to see all of you here today and especially to see many friends and colleagues! I want to thank Nick Laringakis, AHI’s Executive Director, for his kind invitation to this Noon Forum, to speak to you on the subject of the Battle of Crete, an event which as it turns out, was pivotal in the eventual defeat of the Nazis. As a brief introduction, I was born in small village high up in the Psiloritis Mountains in Heraklion Crete. I came to the United States 35 years ago, as a young Engineering student, and somehow never managed to find my way back, for a good reason perhaps! Over the years, besides running a Design Office with a world-wide Architectural/Engineering practice, I have always found it necessary to be involved with the Greek-American and Cretan American community. Currently, I am serving as President of the Pancretan Association of America, an umbrella organization of some and 8,000 members organized in 84 local Chapters around the country. Although an Engineer by training and profession, History has always captivated me since I was a young man! Particularly the history of the place of my birth, Crete, and the constant struggles of its inhabitants against foreign invaders and conquerors for many centuries. In particular the Battle of Crete against the German invaders during World War II and the subsequent Resistance against the Nazi occupation of the island, were such events that have captured my imagination, especially since both my parents lived through them, and years later 1 recounted to me and my sister on many occasions, their recollections and hardships during those trying times! The Cretan version of the popular song of Digenis Akritas goes like this…. -

Cretan Association of South Australia Κρητικός Σύνδεσμος Νότιας Αυστραλίας

CRETAN FEDERATION OF AUSTRALIA & NEW ZEALAND 02 80TH ANNIVERSARY OF THE BATTLE OF CRETE THE ODE “They shall grow not old, as we that are left grow old; Age shall not weary them, nor the years condemn. At the going down of the sun and in the morning We will remember them.” Η ΩΔΗ Δεν θα γεράσουν σαν εμάς, που μείναμε να γεράσουμε, Τα γηρατειά δεν θα τους κουράσουν, Ούτε τα χρόνια θα τους καταδικάσουν Κατά την δύση του ηλίου, και το πρωί, Θα τους θυμόμαστε 80TH ANNIVERSARY OF THE BATTLE OF CRETE 03 Pancretan Association Cretan Brotherhood of of Melbourne - Australia Melbourne & Victoria P.O. Box 4512, 148 - 150 Nicholson Street, Knox City Centre, VIC 3152 East Brunswick, VIC 3057 ΕΤΩΣ ΙΔΡΥΣΕΩΣ 1980 Postal Address: Cretan Association Cretan Association P.O. Box 280 of Queensland Preston VIC 3072, of Sydney & N.S.W. Melbourne, Australia. PO Box 5007, 1/57 Sydenham Road, West End, QLD 4101 Marrickville, NSW 2204 Telephone: +61 419 856 736 Email: [email protected] Cretan Association of Website: Cretan Association Canberra & Districts www.cretan.com.au of New Zealand PO Box 263, Facebook: 7 Bury Grove Strathmore Woden, ACT 2606 Cretan Federation Of Australia Wellington 6022, NZ And New Zealand Cretan Association Cretan Brotherhood of Cretan Association of South Australia Western Australia of Tasmania 220 Port Road, 39 Paperbark Way, 54 Lipscombe Avenue, Alberton, S.A. 5014 Morley, WA 6062 Sandy Bay, TAS 7005 04 80TH ANNIVERSARY OF THE BATTLE OF CRETE Cretan Federation of Australia & New Zealand National Executive Tony Tsourdalakis Herc Kaselakis -

Battle of C Rete BATTLE of CRETE

BATTLE OF CRETE Dates: 26 April - 02 May 2020 (6 Nights/7 Days) Battle of Crete Total Price (Per Person)*: 1550€ (sharing 2 persons) 200€ (plus for single supplement) *Special prices for groups Day 1 – Sunday 26 April - Arrival Day 3 – Tuesday 28 April – Maleme - Maleme airfield - Arrival at Chania Airport - 2 stands, battle development - Travel to Hotel - Galatas - Ice breaking drink - 2 stands, battle development - Return to Chania Day 2 – Monday 27 April - Study Day 4 - Wednesday 29 April-Souda - Study period Bay - Souda Cemetery - Souda Bay - Free afternoon - Chania - Battle development - Travel to Retymnon - Overnight in Rethymnon *Maleme Airport Day 5-Thursday 30 April - Rethymno Day 7 –Saturday 02 May–Departure - Battle for Rethymno - 3 stands, battle development. - Travel to the Heraklio Airport - Travel to Heraklio - Departure - Overnight in Heraklio Day 6–Friday 01 May – Heraklio - Battle for Heraklio - 2 stands, battle development - Knossos archaeological site Battle of Crete - Return to Heraklio - Group dinner What is Included What is NOT Included 3*/4* hotel accommodation (basic) Flights costs including breakfast Pick up transport from/to airport Information pack Evening presentations (where appropriate) All transportation costs All entrance fees All presentations in battlefields Tour manager available day and night All dinners Bottled water each day Farewell dinner Memorabilia gift of Crete War Battle Map of Greece Recommended Reading List - Antill, Peter, Crete 1941 Germany's Lightning Airborne Assault, London: Osprey 2005. - Beevor, Anthony, Crete The Battle and the Resistance, John Murray, 2005. - Ewer, Peter, Forgotten Anzacs: The Campaign in Greece 1941, Victoria: Scribe, 2016. - Kippenberger, Howard, Infantry Brigadier, London: Oxford University Press, 1961. -

Reports of Overseas Travel Undertaken by Members of Parliament for Three Months Ended 30 September 2014 Funded by Th E Parliamentary Travel Allowance

REPORTS OF OVERSEAS TRAVEL UNDERTAKEN BY MEMBERS OF PARLIAMENT FOR THREE MONTHS ENDED 30 SEPTEMBER 2014 FUNDED BY TH E PARLIAMENTARY TRAVEL ALLOWANCE MEMBERS OF PARLIAMENT LBAKER MLA 15~Jun - 14 14-Jul-14 LONDON, INVESTIGATE FUNCTIONS $5,918 SCOTLAND, UNDERTAKEN BY CHILDREN'S WALES COMMISS IONERS IN ENGLAND, SCOTLAND AND WALES. HON C HOLT MLC 27-Jun -14 25-Jul-14 CANADA & USA EXPLORE NEW MODELS AND $18,677 TOOLS FOR BUILDING THE CAPACITY OF REGIONAL LEADERS INCLUDING ABORIGINAL COMMUNITIES TO REVITALISE THROUGH LEADERSHIP. J QUIGLEY MLA 29-Jun-14 9-Aug-14 ITALY ATIEND THE EUROPEANI $7,111 ASIAN LEGAL CONFERENCE INCLUDING SESSIONS ON REFUGEE AND OTHER AREAS OF LAW. A MITCHELL MLA 1-Ju l-14 11 -Jul-14 LONDON, ATIEND VARIOUS MEETINGS S2,024 EDINBURGH & EXCHANGING INFORMATION DUBAI ON YOUTH ENGAGEMENT AND MENTAL HEALTH ISSUES OF EMPLOYEES. INVITED TO SPEAK AT THE WOMEN IN MINING UK RECEPTION. T KRSTICEVIC MLA 8-Jul-14 19-Jul-14 GREECE ATIEND THE PARLIAMENTARY 812,050 ANZAC STUDY AND CULTURAL TOUR OF GREECE UNDERTAKING SITE VISITS AND VARIOUS MEETINGS. HON M LEWIS MLC 8-Jul-14 19-Jul-14 GREECE ATIEND THE PARLIAMENTARY 810,453 ANZAC STUDY AND CULTURAL TOUR OF GREECE UNDERTAKING SITE VISITS, INSPECT THE MAIN PORT, VISIT AND RECEIVE BRIEF ON THE ATHENS UNDERGROUND METRO SYSTEM AND ATIEND VARIOUS MEETINGS. F ALBAN MLA 8-Jul-14 19-Jul-14 GREECE ATIEND THE PARLIAMENTARY $14,698 ANZAC STUDY AND CULTURAL TOUR OF GREECE UNDERTAKING HISTORICAL SITE VISITS AND ATIEND OFFICIAL MEETINGS AT THE GREEK PARLIAMENT. HON J CHOWN MLC 8-Jul-14 21-Jul-14 GREECE COMPARE OPERATIONS OF 811,420 THE GREEK AND AUSTRALIAN PARLIAMENTARY SYSTEMS, INVESTIGATE TRADE & BUSINESS OPPORTUNITIES AND LEARN FROM THE RECENT BUILDING OF A LARGE SCALE UNDERGROUND LIGHT RAIL SYSTEMS SUCH AS ATHENS. -

Mediterranean Front

Mediterranean Front The Desert War , #1 The Year of Wavell, 1940 -41 by Alan Moorehead, 1910-1983 Published: 1941 J J J J J I I I I I Table of Contents Preface & Chapter 1 … thru … Chapter 19 J J J J J I I I I I Preface THE WAR in Africa and the Middle East fell naturally into three phases, each lasting twelve months. At first General Wavell had command from 1940 to 1941, and that was the year of tremendous experiments, of thrusting about in the dark; the year of bluff and quick movement when nobody knew what was going to happen. Whole armies and fleets were flung about from one place to another, and in its frantic efforts to find a new equilibrium the Middle East erupted at half a dozen places at once. At one stage Wavell had five separate campaigns on his hands—the Western Desert, Greece, Crete, Italian East Africa and Syria—and there were other side- shows like Iraq and British Somaliland as well. Most of this was essentially colonial warfare carried out with small groups of men using weapons that would be regarded as obsolete now. Looking back, I see what a feeling of excitement and high adventure we had then when we went off on these little isolated expeditions. We did not quite realise the real grimness of war except at certain moments. The honours between the sides were fairly even. The Germans held Greece and Crete; we held Syria, Abyssinia and all Italian East Africa. The Axis and the British were balanced in the desert. -

The Battle of Greece and Crete an Australian Hellenic Connection

THE BATTLE OF GREECE AND CRETE AN AUSTRALIAN HELLENIC CONNECTION BACKGROUND The Hellenic people had always been recalcitrant and reluctant boarders in their own countries under Ottoman landlords and it is no secret that freedom burned deeply in their souls. This hunger for freedom was carried on through successive generations after the wars of independence and all men of military age served for a period of two years of more under the Hellenic flag. The Hellenic Republic had therefore been fighting to keep alive its very existence and way of life along many of its land and maritime borders. THE BATTLE IN GREECE When the phony war between that of Great Britain the Nazi Germany World War II was over and the real battle lines were established, Mussolini, the Italian dictator wishing to emulate the Roman emperors embarked upon a journey of expansion by attacking weaker nations within his so called sphere of influence. Ethiopia, Libya and Greece much to the chagrin of his Nazi ally in Hitler. The Hellenic response of “OHI” by Metaxas to Mussolini’s representative on the 28 October 1940 did not come as a complete surprise to the Hellenic people. The Hellenic forces knew of the looming threat from the West and had secretly prepared for such an exigency against their Italian neighbours. A humiliated Mussolini looked towards his Nazi ally in Hitler to make things good and bring about the equilibrium necessary for further aggression in the strategy of expansion. Hitler was not amused by the antics of his brother in arms Mussolini, who strut the world stage as if he were a Roman emperor. -

The Battle of Greece & Crete an Australian Hellenic Connection

THE BATTLE OF GREECE & CRETE AN AUSTRALIAN HELLENIC CONNECTION The Voice from the Pavement - Peter Adamis DISCLAIMER. This article is but a mere grain of text amongst the thousands of text books that have been written about the Battle of Greece and Crete. As the author, I apologize for having transgressed in areas where others know better in terms of the battles referred to in the article. It is not possible to describe the horrors of war, nor is it possible to highlight the decisions being made by the men on the ground during a time oh high expectations and. This article skims but the surface and lightly at that in trying to bring together but a small thread of what occurred during the Battle of Greece and Crete. The author also apologizes for any errors be they of grammar or text related, that may have crept in unnoticed and will gladly make amends as required. PREAMBLE. The Hellenic people in conjunction with their Serbian orthodox brethren had always been recalcitrant and reluctant boarders in their own countries under Ottoman landlords and it is no secret that freedom burned deeply in their souls. This hunger for freedom was carried on through successive generations after the wars of independence and all men of military age served for a period of two years of more under the Hellenic flag. The Hellenic Republic had therefore been fighting to keep alive its very existence and way of life along many of its land and maritime borders. THE BATTLE IN GREECE. When the phony war between that of Great Britain the Nazi Germany World War II was over, the real battle lines were established.