Nomination of Historic Building, Structure, Site, Or Object

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

View the Program Book

PRESERVATION ACHIEVEMENT AWARDS 2021 AWARDS ACHIEVEMENT PRESERVATION e join eas us pl in at br ing le e c 1996 2021 p y r e e e a c s rs n e a rv li ati o n al 2021 PRESERVATION ACHIEVEMENT AWARDS WEDNESDAY, JUNE 9, 2021 CONGRATULATIONS TO THE 2021 PRESERVATION ACHIEVEMENT AWARD HONOREES Your knowledge, commitment, and advocacy create a better future for our city. And best wishes to the Preservation Alliance as you celebrate 25 years of invaluable service to the Greater Philadelphia region. pmcpropertygroup.com 1 PRESERVATION ACHIEVEMENT AWARDS 2021 WELCOME TO THE 2021 PRESERVATION ACHIEVEMENT AWARDS HONORING THE INDIVIDUALS, ORGANIZATIONS, BUSINESSES, AND PROJECTS THROUGHOUT GREATER PHILADELPHIA THAT EXEMPLIFY OUTSTANDING ACHIEVEMENT IN HISTORIC PRESERVATION TABLE OF CONTENTS Our Sponsors . 4 Executive Director’s Welcome . .. 6 Board of Directors . 8 Celebrating 25 Years: A Look Back . 9 Special Recognition Awards . 11 Advisory Committee. 11 James Biddle Award . 12 Board of Directors Award . 13 Rhoda and Permar Richards Award. 13 Economic Impact Award . 14 Preservation Education Awards . 14-15 John Andrew Gallery Community Action Awards . 15-16 Public Service Awards . 16-17 Young Friends of the Preservation Alliance Award . 17 AIA Philadelphia Henry J . Magaziner Award . .. 18 AIA Philadelphia Landmark Building Award . .. 18 Members of the Grand Jury . .. 19 Grand Jury Awards and Map . 20 In Memoriam . 46 Video by Mitlas Productions LLC | Graphic design by Peltz Creative Program editing by Fabien Communications 25TH ANNIVERSARY OF THE PRESERVATION ALLIANCE FOR GREATER PHILADELPHIA 2 3 PRESERVATION ACHIEVEMENT AWARDS 2021 OUR SPONSORS ALABASTER PMC Property Group Brickstone IBEW Local Union 98 Post Brothers MARBLE A. -

Finding Aid for the Mellor, Meigs & Howe Collection in The

George Howe, P.S.F.S. Building, ca. 1926 THE ARCHITECTURAL ARCHIVES OF THE UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA MELLOR, MEIGS & HOWE COLLECTION (Collection 117) A Finding Aid for The Mellor, Meigs & Howe Collection in The Architectural Archives, University of Pennsylvania © 2003 The Architectural Archives of the University of Pennsylvania. All rights reserved. The Architectural Archives, University of Pennsylvania Mellor, Meigs & Howe Collection Finding Aid Archival Description Descriptive Summary Title: Mellor, Meigs & Howe Collection, 1915-1975, bulk 1915-1939. Coll. ID: 117 Origin: Mellor, Meigs & Howe, Architects, and successor, predecessor and related firms. Extent: Architectural drawings: 1004 sheets; Photographs: 83 photoprints; Boxed files: 1/2 cubic foot. Repository: The Architectural Archives, University of Pennsylvania 102 Meyerson Hall Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104-6311 (215) 898-8323 Abstract: The Mellor, Meigs & Howe Collection comprises architectural records related to the practices of Mellor, Meigs & Howe and its predecessor and successor firms. The bulk of the collection documents architectural projects of the following firms: Mellor, Meigs & Howe; Mellor & Meigs; Howe and Lescaze; and George Howe, Architect. It also contains materials related to projects of the firms William Lescaze, Architect and Louis E. McAllister, Architect. The collection also contains a small amount of personal material related to Walter Mellor and George Howe. Indexes: This collection is included in the Philadelphia Architects and Buildings Project, a searchable database of architectural research materials related to architects and architecture in Philadelphia and surrounding regions: http://www.philadelphiabuildings.org Cataloging: Collection-level records for materials in the Architectural Archives may be found in RLIN Eureka, the union catalogue of members of the Research Libraries Group. -

Penn Center Plaza Transportation Gateway Application ID 8333219 Exhibit 1: Project Description

MULTIMODAL TRANSPORTATION FUND APPLICATION Center City District: Penn Center Plaza Transportation Gateway Application ID 8333219 Exhibit 1: Project Description The Center City District (CCD), a private-sector sponsored business improvement district, authorized under the Commonwealth’s Municipality Authorities Act, seeks to improve the open area and entrances to public transit between the two original Penn Center buildings, bounded by Market Street and JFK Boulevard and 15th and 16th Streets. In 2014, the CCD completed the transformation of Dilworth Park into a first class gateway to transit and a welcoming, sustainably designed civic commons in the heart of Philadelphia. In 2018, the City of Philadelphia completed the renovations of LOVE Park, between 15th and 16th Street, JFK Boulevard and Arch Street. The adjacent Penn Center open space should be a vibrant pedestrian link between the office district and City Hall, a prominent gateway to transit and an attractive setting for businesses seeking to capitalize on direct connections to the regional rail and subway system. However, it is neither well designed nor well managed. While it is perceived and used as public space, its divided ownership between the two adjacent Penn Center buildings and SEPTA has long hampered efforts for a coordinated improvement plan. The property lines runs east/west through the middle of the plaza with Two Penn Center owning the northern half, 1515 Market owning the southern half and neither party willing to make improvements without their neighbor making similar improvements. Since it opened in the early 1960s, Penn Center plaza has never lived up to its full potential. The site was created during urban renewal with the demolition of the above ground, Broad Street Station and the elevated train tracks that ran west to 30th Street. -

Program Code Title Date Start Time CE Hours Description Tour Format

Tour Program Code Title Date Start Time CE Hours Description Accessibility Format ET101 Historic Boathouse Row 05/18/16 8:00 a.m. 2.00 LUs/GBCI Take an illuminating journey along Boathouse Row, a National Historic District, and tour the exteriors of 15 buildings dating from Bus and No 1861 to 1998. Get a firsthand view of a genuine labor of Preservation love. Plus, get an interior look at the University Barge Club Walking and the Undine Barge Club. Tour ET102 Good Practice: Research, Academic, and Clinical 05/18/16 9:00 a.m. 1.50 LUs/HSW/GBCI Find out how the innovative design of the 10-story Smilow Center for Translational Research drives collaboration and accelerates Bus and Yes SPaces Work Together advanced disease discoveries and treatment. Physically integrated within the University of Pennsylvania’s Perelman Center for Walking Advanced Medicine and Jordan Center for Medical Education, it's built to train the next generation of Physician-scientists. Tour ET103 Longwood Gardens’ Fountain Revitalization, 05/18/16 9:00 a.m. 3.00 LUs/HSW/GBCI Take an exclusive tour of three significant historic restoration and exPansion Projects with the renowned architects and Bus and No Meadow ExPansion, and East Conservatory designers resPonsible for them. Find out how each Professional incorPorated modern systems and technologies while Walking Plaza maintaining design excellence, social integrity, sustainability, land stewardshiP and Preservation, and, of course, old-world Tour charm. Please wear closed-toe shoes and long Pants. ET104 Sustainability Initiatives and Green Building at 05/18/16 10:30 a.m. -

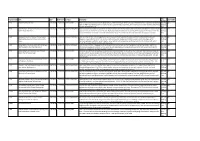

Historic-Register-OPA-Addresses.Pdf

Philadelphia Historical Commission Philadelphia Register of Historic Places As of January 6, 2020 Address Desig Date 1 Desig Date 2 District District Date Historic Name Date 1 ACADEMY CIR 6/26/1956 US Naval Home 930 ADAMS AVE 8/9/2000 Greenwood Knights of Pythias Cemetery 1548 ADAMS AVE 6/14/2013 Leech House; Worrell/Winter House 1728 517 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 519 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 600-02 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 2013 601 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 603 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 604 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 605-11 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 606 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 608 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 610 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 612-14 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 613 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 615 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 616-18 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 617 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 619 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 629 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 631 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 1970 635 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 636 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 637 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 638 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 639 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 640 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 641 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 642 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 643 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 703 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 708 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 710 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 712 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 714 ADDISON ST Society Hill -

Adaptive Reuse: Recent Hotel Conversions in Downtown Philadelphia Catherine S

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Theses (Historic Preservation) Graduate Program in Historic Preservation 1-1-2005 Adaptive Reuse: Recent Hotel Conversions in Downtown Philadelphia Catherine S. Jefferson University of Pennsylvania Follow this and additional works at: http://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses Part of the Historic Preservation and Conservation Commons Jefferson, Catherine S., "Adaptive Reuse: Recent Hotel Conversions in Downtown Philadelphia" (2005). Theses (Historic Preservation). 30. http://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/30 Presented to the Faculties of the University of Pennsylvania in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Historic Preservation 2005. Advisor: David Hollenberg This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. http://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/30 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Adaptive Reuse: Recent Hotel Conversions in Downtown Philadelphia Disciplines Historic Preservation and Conservation Comments Presented to the Faculties of the University of Pennsylvania in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Historic Preservation 2005. Advisor: David Hollenberg This thesis or dissertation is available at ScholarlyCommons: http://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/30 ADAPTIVE REUSE: RECENT HOTEL CONVERSIONS IN DOWNTOWN PHILADELPHIA Catherine Sarah Jefferson A THESIS in Historic Preservation Presented to the Faculties of the University of Pennsylvania in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE IN HISTORIC PRESERVATION 2005 _____________________________ _____________________________ Advisor Reader David Hollenberg John Milner Lecturer in Historic Preservation Adjunct Professor of Architecture _____________________________ Program Chair Frank G. Matero Associate Professor of Architecture ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This thesis would not have been possible without the assistance and support of a number of people. -

Theodore Roosevelt Middle School), in Assessor's Parcel Block No. 1061, Lot No

FILE NO. 180003 ORDINANCE NO. 37-19 1 [Planning Code - Landmark Designation - 460 Arguello Boulevard (aka Theodore Roosevelt Middle School)] 2 3 Ordinance amending the Planning Code to designate 460 Arguello Boulevard (aka 4 Theodore Roosevelt Middle School), in Assessor's Parcel Block No. 1061, Lot No. 049, 5 as a Landmark under Article 10 of the Planning Code; affirming the Planning 6 Department's determination under the California Environmental Quality Act; and 7 making public necessity, convenience, and welfare findings under Planning Code, 8 Section 302, and findings of consistency with the General Plan, and the eight priority 9 policies of Planning Code, Section 101.1. 10 NOTE: Unchanged Code text and uncodified text are in plain Ariai font. Additions to Codes are in single-underline italics Times New Roman font. 11 Deletions to Codes are in strikf!through italics Times New Roman font. Board amendment additions are in double-underlined Arial font. 12 Board amendment deletions are in strikethrough Arial font. Asterisks (* * * *) indicate the omission of unchanged Code 13 subsections or parts of tables. 14 15 Be it ordained by the People of the City and County of San Francisco: 16 Section 1. Findings. 17 (a) CEQA and Land Use Findings. 18 (1) The Planning Department has determined that the proposed Planning Code 19 amendment is subject to a Categorical Exemption from the California Environmental Quality 20 Act (California Public Resources Code section 21000 et seq., "CEQA") pursuant to Section 21 15308 of the Guidelines for implementation of the statute for actions by regulatory agencies 22 for protection of the environment (in this case, landmark designation). -

David Mcgirr

1 BYERA HADLEY TRAVELLING SCHOLARSHIP REPORT – DAVID MCGIRR Byera Hadley Scholarship Report Student: David McGirr - UTS Project Title: Modernising the Modernists Proposal: To investigate and analyse current and recent international examples of the modification and adaptive reuse of Modernist buildings. Abstract As the Modernist Project recedes ever further into history, and a contemporary society moves forward, the once progressive and dynamic Modernist building finds itself in the unusual position of becoming urban artifact. Modernism is the ‘new heritage’, and as such faces a challenge to ensure its future survival and relevance.1 This Modernist heritage has shown itself, particularly in Australia, which has a rich history of Architecture from the Modernist era2, to be especially vulnerable to perceived obsolescence and subsequent demolition. Controversy and publicity surrounding recent projects and proposals such as alterations to The National Gallery of Australia, and UTS Kuringai Campus demonstrate that not only is the issue of modification to Modernist buildings a current and relevant topic, but also a matter which would benefit from an objective evaluation of overseas case studies. Often Modernist buildings do not receive the same amount of public support or Government protection as buildings from the more distant past. Subsequently it is the view of many (from preservationists to the progressives) that, in order to remain in some way extant, Modernist buildings must be true to their inherent ideological tenets. In other words, they need to stay “modern”. Significant modification and adaptive reuse3, is often seen as the most viable means of sustaining a historic building, yet this practice is one which has only recently been applied to Modernist buildings. -

Agnes Scott College Bulletin: Catalogue Number 1916-1917

SERIES 14 NUMBER 3 AGNES SCOTT COLLEGE BULLETIN CATALOGUE NUMBER 1916-1917 ENTERED AS SECOND-CLASS MATTER AT THE POST OFFICE. DECATUR, GEORGIA I AGNES SCOTT COLLEGE BULLETIN CATALOGUE NUMBER 1916-1917 BOARD OF TRUSTEES J. K. Orr, Chairman Atlanta F. H. Gaines Decatur C, M. Candler Decatur J. G. Patton Decatur George B. Scott Decatur W. S. Kendrick Atlanta John J. Eagan Atlanta L. C. Mandeville Carrollton, Ga. D. H. Ogden Atlanta K. G. Matheson Atlanta J. T. LuPTON Chattanooga, Tenn. J. P. McCallie Chattanooga, Tenn. W. C. Vereen Moultrie, Ga. L. M. Hooper Selma, Ala. J. S. Lyons Atlanta Frank M, Inman Atlanta EXECUTIVE AND ADVISORY COMMITTEE C. M. Candler John J. Eagan J. K. Orr F. H. Gaines (r. "R. ScOTT FINANCE COMMITTEE Frank M. Inman J. T. Lupton G. B. Scott W. C. Vereen L. C. Mandeville Agnes Scott College CALENDAR 1917—September 18, Dormitories open for reception of Students. September 19, 10 A. M., Session opens. September 18-20, Registration and Classification of Students. September 21, Classes begin. November 39, Tranksgiving Day. December 19, 1:20 P. M., to January 3, 8 A. M., Christmas Eecess. 1918—January 15, Mid-Year Examinations begin. January 26, Second Semester begins. January 28, Classes Resumed. February 22, Colonel George W. Scott's Birthday. March 29, 1:20 P. M., to April 2, 8 A. M., Spring Vacation. April 26, Memorial Day. May 14, Final Examinations begin. May 26, Baccalaureate Sermon. May 28, Alumnae Day, May 29, Commencement Day. Officers and Instructors OFFICERS OF INSTRUCTION AND GOVERNMENT 1916-1917 (arranged in order of appointment) F. -

Evolution of a Modern American Architecture: Adding to Square Shadows

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Theses (Historic Preservation) Graduate Program in Historic Preservation 1-1-2007 Evolution of A Modern American Architecture: Adding to Square Shadows Fon Shion Wang University of Pennsylvania Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses Part of the Historic Preservation and Conservation Commons Wang, Fon Shion, "Evolution of A Modern American Architecture: Adding to Square Shadows" (2007). Theses (Historic Preservation). 93. https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/93 A Thesis in Historic Preservation Presented to the Faculties of the University of Pennsylvania in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Historic Preservation 2007. Advisor: David G. De Long This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/93 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Evolution of A Modern American Architecture: Adding to Square Shadows Disciplines Historic Preservation and Conservation Comments A Thesis in Historic Preservation Presented to the Faculties of the University of Pennsylvania in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Historic Preservation 2007. Advisor: David G. De Long This thesis or dissertation is available at ScholarlyCommons: https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/93 EVOLUTION OF A MODERN AMERICAN ARCHITECTURE: ADDING TO SQUARE SHADOWS Fon Shion Wang A THESIS In Historic Preservation Presented to the Faculties of the University of Pennsylvania in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE IN HISTORIC PRESERVATION 2007 ________________________ ______________________________ Advisor Reader David G. De Long John Milner Professor Emeritus of Architecture Adjunct Professor of Architecture _______________________________ Program Chair Frank G. -

The Architecture of the Bryn Mawr Campus George E

Bryn Mawr College Scholarship, Research, and Creative Work at Bryn Mawr College Architecture, Grounds, and History Facilities 1978 The Architecture of the Bryn Mawr Campus George E. Thomas Published in Bryn Mawr Now. The ad te is not visible on the document and is based on a reference to the lecture being given during the Centennial year of Joseph Taylor's will. Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy . Follow this and additional works at: http://repository.brynmawr.edu/facilities_history Part of the Architecture Commons, and the Educational Administration and Supervision Commons Citation Thomas, George E., "The Architecture of the Bryn Mawr Campus" (1978). Architecture, Grounds, and History. Paper 5. http://repository.brynmawr.edu/facilities_history/5 This paper is posted at Scholarship, Research, and Creative Work at Bryn Mawr College. http://repository.brynmawr.edu/facilities_history/5 For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE ARCHITECTURE OF THE BRYN MAWR CAMPUS "AI the en d of the cenlury, Rockefeller Hall. ,closing the campus off to the west, directing the attention inwards, back to the Co ll ege center." The Rockefeller Hall archway and towers under construc tion. by GEORGE THOMAS Visiting Lecturer In Growth and Structure of CIties Excerpts from a memorial lecture for the late John Forsythe, Trflasurer of Bryn Mawr Col/ege for 24 years, given by the noted architectural historian George Thomas, who this year Is teaching several courses In the College's interdepartmental cities program, including one this semester on PhI/adel phia architecture from the 19'th century Greek , Revival period to today's nationally recognized "PhI/ adelphia School." . -

Aohwmpjz2014120054q0

Interview with Robert Heckert 12/28/77 I'm Robert Heckert, a good friend of Walter's, who has asked me to come here to record some impressions and recollections of the city of Philadelphia as I knew it back as far as 50 years ago. I came to the city in 1927 to settle down and was then associated with the Philadelphia Ethical Culture Society. it was not until 1943 that I became a radio commentator on station WIBG at that time. And a little later on with station KYW, where I became fairly well known throughout the Philadelphia area. Walter would like me to characterize if I would some of the early mayors of the city going back to that time. Well, the first one I remember clearly and the first one with whom I had some contact was Mayor Harry Mackey. As everybody knows at that time all Philadelphia mayors were Republicans. And Harry Mackey was a good Republican. A good soldier in the Vare machine organization. I>want to say a good thing about Mayor Mackey. He came into the mayors office in January 1928. It was a good time in the city and in the country, economically speaking, and we were enjoying great prosperity and Philadelphia was no exception to that rule. But in the middle of Mayor Mackey's term the great Depression struck the nation and of course Philadelphia along with it. And I remember very distinctly that there were hundreds, literally many hundreds of unemployed absolutely destitute men who were housed in an old warehouse around 16th and Hamilton streets where they were given simple food and shelter.