Director's Portrait Alain Tanner

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

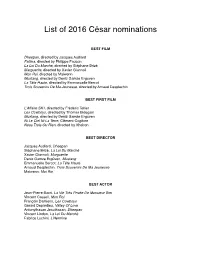

List of Cesar Nominations 2016

List of 2016 César nominations! ! ! ! BEST! FILM! Dheepan, directed by Jacques Audiard! Fatima, directed by Philippe Faucon! La Loi Du Marché, directed by Stéphane Brizé! Marguerite, directed by Xavier Giannoli! Mon Roi, directed by Maiwenn! Mustang, directed by Deniz Gamze Erguven! La Tête Haute, directed by Emmanuelle Bercot! !Trois Souvenirs De Ma Jeunesse, directed by Arnaud Desplechin! ! ! BEST FIRST FILM! L’Affaire SK1, directed by Frédéric Tellier! Les Cowboys, directed by Thomas Bidegain! Mustang, directed by Deniz Gamze Erguven! Ni Le Ciel Ni La Terre, Clément Cogitore! !Nous Trois Ou Rien, directed by Kheiron! ! ! BEST DIRECTOR! Jacques Audiard, Dheepan! Stéphane Brizé, La Loi Du Marché! Xavier Giannoli, Marguerite! Deniz Gamze Ergüven, Mustang! Emmanuelle Bercot, La Tête Haute! Arnaud Desplechin, Trois Souvenirs De Ma Jeunesse! !Maïwenn, Moi Roi! ! ! BEST ACTOR! Jean-Pierre Bacri, La Vie Très Privée De Monsieur Sim! Vincent Cassell, Mon Roi! François Damiens, Les Cowboys! Gérard Depardieu, Valley Of Love! Antonythasan Jesuthasan, Dheepan! Vincent Lindon, La Loi Du Marché! !Fabrice Luchini, L’Hermine! ! ! ! BEST ACTRESS! Loubna Abidar, Much Loved! Emmanuelle Bercot, Mon Roi! Cécile de France, La Belle Saison! Catherine Deneuve, La Tête Haute! Catherine Frot, Marguerite! Isabelle Huppert, Valley Of Love! !Soria Zeroual, Fatima! ! BEST SUPPORTING ACTOR! Michel Fau, Marguerite! Louis Garrel, Mon Roi! Benoit Magimel, La Tête Haute! André Marcon, Marguerite! !Vincent Rottiers, Dheepan! ! ! BEST SUPPORTING ACTRESS! Sara Forestier, -

MARY SHELLEY (Run), P

JUNE 018 GAZETTE 2 ■ Vol. 46, No. 6 Rediscovering Rediscovering Alain Tanner LA SALAMANDRE, June 9, 14 MORE FRIDAY MATINEES! OPEN-CAPTIONED SCREENINGS! ALSO: 164 N. State Street Trnka, Inoue, Gunn, Clouzot www.siskelfilmcenter.org CHICAGO PREMIERE! THOMAS PIPER IN PERSON! 2017, Thomas Piper, USA, 75 min. “A pleasure on multiple fronts: sensorially, conceptually, narratively.”—Jennifer Reut, Landscape Architecture Magazine Five seasons in the gardens and career of Dutch garden designer Piet Oudolf, creator of Chicago’s acclaimed Lurie Garden in Millennium Park, are traced in this lush documentary that blooms with details of Oudolf’s other high-profile projects including Manhattan’s High Line and the waterfront Battery Gardens. Beginning with an autumn walk through the designer’s own sprawling but intricately planted garden in the Dutch village of Hummelo, the film conveys his deep and thoughtful appreciation for botanical life in all its seasons. DCP digital. (BS) Director Thomas Piper will be present for audience discussion on Friday at 7:45 pm. The 7:45 pm screening on Fri., June 15, is a Movie Club event (see p. 3). FIVE June 15—21 Fri., 6/15 at 2:15 pm, 6 pm, and 7:45 pm; Sat., 6/16 at 6:15 pm; SEASONS Sun., 6/17 at 2 pm; Mon., 6/18 at 6 pm; THE GARDENS Tue., 6/19 at 8:15 pm; OF PIET OUDOLF Wed., 6/20 at 6 pm; Thu., 6/21 at 8:30 pm CHICAGO PREMIERE! “Vivid and beautifully meditative memory piece on BOOM the downtown New York art and music scene of the late 1970s and early ‘80s.” THEFOR LATE TEENAGE REAL: YEARS —Chris Barsanti, The Playlist OF JEAN-MICHEL BASQUIAT 2017, Sara Driver, USA, 78 min. -

Here Was Obviously No Way to Imagine the Event Taking Place Anywhere Else

New theatre, new dates, new profile, new partners: WELCOME TO THE 23rd AND REVAMPED VERSION OF COLCOA! COLCOA’s first edition took place in April 1997, eight Finally, the high profile and exclusive 23rd program, years after the DGA theaters were inaugurated. For 22 including North American and U.S Premieres of films years we have had the privilege to premiere French from the recent Cannes and Venice Film Festivals, is films in the most prestigious theater complex in proof that COLCOA has become a major event for Hollywood. professionals in France and in Hollywood. When the Directors Guild of America (co-creator This year, our schedule has been improved in order to of COLCOA with the MPA, La Sacem and the WGA see more films during the day and have more choices West) decided to upgrade both sound and projection between different films offered in our three theatres. As systems in their main theater last year, the FACF board an example, evening screenings in the Renoir theater made the logical decision to postpone the event from will start earlier and give you the opportunity to attend April to September. The DGA building has become part screenings in other theatres after 10:00 p.m. of the festival’s DNA and there was obviously no way to imagine the event taking place anywhere else. All our popular series are back (Film Noir Series, French NeWave 2.0, After 10, World Cinema, documentaries Today, your patience is fully rewarded. First, you will and classics, Focus on a filmmaker and on a composer, rediscover your favorite festival in a very unique and TV series) as well as our educational program, exclusive way: You will be the very first audience to supported by ELMA and offered to 3,000 high school enjoy the most optimal theatrical viewing experience in students. -

The Beauty of the Real: What Hollywood Can

The Beauty of the Real The Beauty of the Real What Hollywood Can Learn from Contemporary French Actresses Mick LaSalle s ta n f or d ge n e r a l b o o k s An Imprint of Stanford University Press Stanford, California Stanford University Press Stanford, California © 2012 by Mick LaSalle. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system without the prior written permission of Stanford University Press. Printed in the United States of America on acid-free, archival-quality paper Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data LaSalle, Mick, author. The beauty of the real : what Hollywood can learn from contemporary French actresses / Mick LaSalle. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-8047-6854-2 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Motion picture actors and actresses--France. 2. Actresses--France. 3. Women in motion pictures. 4. Motion pictures, French--United States. I. Title. PN1998.2.L376 2012 791.43'65220944--dc23 2011049156 Designed by Bruce Lundquist Typeset at Stanford University Press in 10.5/15 Bell MT For my mother, for Joanne, for Amy and for Leba Hertz. Great women. Contents Introduction: Two Myths 1 1 Teen Rebellion 11 2 The Young Woman Alone: Isabelle Huppert, Isabelle Adjani, and Nathalie Baye 23 3 Juliette Binoche, Emmanuelle Béart, and the Temptations of Vanity 37 4 The Shame of Valeria Bruni Tedeschi 49 5 Sandrine Kiberlain 61 6 Sandrine -

Alain Tanner Филм ÑÐ ¿Ð¸ÑÑ ŠÐº (ФилмографиÑ)

Alain Tanner Филм ÑÐ ¿Ð¸ÑÑ ŠÐº (ФилмографиÑ) Light Years Away https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/light-years-away-1402542/actors The Woman from Rose Hill https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-woman-from-rose-hill-18542955/actors The Diary of Lady M https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-diary-of-lady-m-18604474/actors https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/la-vall%C3%A9e-fant%C3%B4me- La vallée fantôme 21647262/actors The Man Who Lost His Shadow https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-man-who-lost-his-shadow-24938017/actors A Flame in My Heart https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/a-flame-in-my-heart-27666257/actors The Salamander https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-salamander-3212693/actors The Middle of the World https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-middle-of-the-world-3224550/actors No Man's Land https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/no-man%27s-land-3342426/actors Nice Time https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/nice-time-3382446/actors Charles, Dead or Alive https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/charles%2C-dead-or-alive-384776/actors Fleurs de sang https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/fleurs-de-sang-48746792/actors Les hommes du port https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/les-hommes-du-port-50184103/actors Messidor https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/messidor-512192/actors Fourbi https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/fourbi-5475762/actors Requiem https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/requiem-56306217/actors The Apprentices https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-apprentices-64732218/actors Jonah Who Will Be 25 in the Year https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/jonah-who-will-be-25-in-the-year-2000- 2000 670633/actors In the White City https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/in-the-white-city-679684/actors Rousseau chez Alain Tanner https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/rousseau-chez-alain-tanner-90159411/actors. -

Une Année Studieuse

Extrait de la publication DU MÊME AUTEUR Aux Éditions Gallimard DES FILLES BIEN ÉLEVÉES MON BEAU NAVIRE (Folio no 2292) MARIMÉ (Folio no 2514) CANINES (Folio no 2761) HYMNES À L’AMOUR (Folio no 3036) UNE POIGNÉE DE GENS. Grand Prix du roman de l’Académie française 1998 (Folio no 3358) AUX QUATRE COINS DU MONDE (Folio no 3770) SEPT GARÇONS (Folio no 3981) JE M’APPELLE ÉLISABETH (Folio no 4270) L’ÎLE. Nouvelle extraite du recueil DES FILLES BIEN ÉLEVÉES (Folio 2 € no 4674) JEUNE FILLE (Folio no 4722) MON ENFANT DE BERLIN (Folio no 5197) Extrait de la publication une année studieuse Extrait de la publication Extrait de la publication ANNE WIAZEMSKY UNE ANNÉE STUDIEUSE roman GALLIMARD © Éditions Gallimard, 2012. Extrait de la publication À Florence Malraux Extrait de la publication Un jour de juin 1966, j’écrivis une courte lettre à Jean-Luc Godard adressée aux Cahiers du Cinéma, 5 rue Clément-Marot, Paris 8e. Je lui disais avoir beaucoup aimé son dernier i lm, Masculin Féminin. Je lui disais encore que j’aimais l’homme qui était derrière, que je l’aimais, lui. J’avais agi sans réaliser la portée de certains mots, après une conversation avec Ghislain Cloquet, rencontré lors du tournage d’Au hasard Balthazar de Robert Bresson. Nous étions demeurés amis, et Ghislain m’avait invitée la veille à déjeuner. C’était un dimanche, nous avions du temps devant nous et nous étions allés nous promener en Normandie. À un moment, je lui parlai de Jean-Luc Godard, de mes regrets au souvenir de trois rencontres « ratées ». -

111714906.Pdf

1 4 Films by Alain Tanner Screening at the Wooden Shoe, 704 South St., Philadelphia. Zine published in collaboration with Shooting Wall. Friday November 2 7PM La Salamandre (The Salamander) 1971 124min. Starring Bulle Ogier, Jean-Luc Bideau, & Jacques Denis Saturday November 3 7 PM Le Milieu du monde (The Middle of the World ) 1974 115min. Starring Olimpia Carlisi, Philippe Léotard, & Juliet Berto Friday November 9 7 PM Jonas qui aura 25 ans en l'an 2000 (Jonah Who Will Be 25 in the Year 2000) 1976 116min. Starring Jean-Luc Bideau, Myriam Boyer, Raymond Bussiéres, Jacques Denis, Roger Jendly, Dominique Labourier, Myriam Mé- ziéres, Miou-Miou, Rufus Saturday November 10 7PM Messidor 1979 123min. Starring Clémentine Amouroux & Catherine Rétouré Contents About Alain Tanner & Resources 3 A Long Introduction 4 Ben Webster Le Milieu du monde 16 Ross Wilbanks Investigating Reality: Character, Idealism, & 19 Political Ideology in Alain Tanner‟s La Salamandre Josh Martin Don‟t Fuck the Boss! 22 Ben Webster 2 About Alain Tanner (courtesy Wikipedia) Alain Tanner (born 6 December 1929, Geneva) is a Swiss film director. Tanner found work at the British Film Institute in 1955, subtitling, translating, and organizing the archive. His first film, Nice Time (1957), a short documen- tary film about Piccadilly Circus during weekend evenings, was made with Claude Goretta. Produced by the British Film Institute Experimental Film Fund, it was first shown as part of the third Free Cinema programme at the Na- tional Film Theatre in May 1957. The debut film won a prize at the film festival in Venice and much critical praise. -

Movie Museum OCTOBER 2012 COMING ATTRACTIONS

Movie Museum OCTOBER 2012 COMING ATTRACTIONS THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY SUNDAY MONDAY 2 Hawaii Premieres! Hawaii Premiere! 2 Hawaii Premieres! TRAIN OF LIFE 2 Hawaii Premieres! LA RAFLE OUR HAPPY LIVES BAD FAITH aka Train de vie SECRETS OF STATE (2010-France/Ger/Hung) aka Nos vies heureuses aka Mauvaise foi (1998-Fr/Bel/Neth/Isr/Rom) aka Secret defense French w/Eng subtitles, w.s (1999-France) (2006-Belgium/France) French w/subtitles & w.s. (2008-France) Jean Reno, Mélanie Laurent. French w/subtitles, w.s. French w/subtitles & w.s. with Lionel Abelanski, Rufus. French w/Eng subtitles, w.s 12:00, 2:15 & 9:00pm only Marie Payen, Sami Bouajila. D: Roschdy Zem. 12:00, 1:45 & 8:15pm only Gerard Lanvin, Vahina Giocante ---------------------------------- 12 & 8pm only 12:00, 1:30 & 8:15pm only ---------------------------------- 12:00, 1:45 & 8:30pm only BAD FAITH ---------------------------------- --------------------------------- Hawaii Premiere! ---------------------------------- aka Mauvaise foi TRAIN OF LIFE SUMMER THINGS LA RAFLE OUR HAPPY LIVES (2006-Belgium/France) aka Train de vie Embrassez qui vous voudrez (2010-France/Ger/Hung) aka Nos vies heureuses French w/subtitles & w.s. (1998-Fr/Bel/Neth/Isr/Rom) (2002-France/UK/Italy) French w/Eng subtitles, w.s (1999-France) Cécile De France, Roschdy French w/subtitles & w.s. French w/subtitles & w.s. Jean Reno, Mélanie Laurent, French w/subtitles, w.s. Zem, Jean-Pierre Cassel. with Lionel Abelanski, Rufus. Charlotte Rampling. Gad Elmaleh, Hugo Leverdez. Marie Payen, Sami Bouajila. 4:30, 6:00 & 7:30pm only 2:30, 4:15 & 6:00pm only 3:00, 4:45 & 6:30pm only 3:45 & 6:00pm only 3:30 & 6:00pm only 4 5 6 7 8 Hawaii Premiere! 50th Anniversary CONVERSATIONS SUMMER THINGS Cuban Missile Crisis PROMETHEUS (2012-US/UK) WITH MY GARDENER (2002-France/UK/Italy) X-MEN: FIRST CLASS (2007-France) French w/subtitles & w.s. -

The Regents of the University of California, Berkeley – UC Berkeley Art Museum & Pacific Film Archive (BAMPFA)

Recordings at Risk Sample Proposal (Fourth Call) Applicant: The Regents of the University of California, Berkeley – UC Berkeley Art Museum & Pacific Film Archive (BAMPFA) Project: Saving Film Exhibition History: Digitizing Recordings of Guest Speakers at the Pacific Film Archive, 1976 to 1986 Portions of this successful proposal have been provided for the benefit of future Recordings at Risk applicants. Members of CLIR’s independent review panel were particularly impressed by these aspects of the proposal: • The broad scholarly and public appeal of the included filmmakers; • Well-articulated statements of significance and impact; • Strong letters of support from scholars; and, • A plan to interpret rights in a way to maximize access. Please direct any questions to program staff at [email protected] Application: 0000000148 Recordings at Risk Summary ID: 0000000148 Last submitted: Jun 28 2018 05:14 PM (EDT) Application Form Completed - Jun 28 2018 Form for "Application Form" Section 1: Project Summary Applicant Institution (Legal Name) The Regents of the University of California, Berkeley Applicant Institution (Colloquial Name) UC Berkeley Art Museum & Pacific Film Archive (BAMPFA) Project Title (max. 50 words) Saving Film Exhibition History: Digitizing Recordings of Guest Speakers at the Pacific Film Archive, 1976 to 1986 Project Summary (max. 150 words) In conjunction with its world-renowned film exhibition program established in 1971, the UC Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive (BAMPFA) began regularly recording guest speakers in its film theater in 1976. The first ten years of these recordings (1976-86) document what has become a hallmark of BAMPFA’s programming: in-person presentations by acclaimed directors, including luminaries of global cinema, groundbreaking independent filmmakers, documentarians, avant-garde artists, and leaders in academic and popular film criticism. -

San Francisco Cinematheque Program Notes

•• * 'i \ ,*" ::iK](Vi4i:,« .%, J'T'^Kf; A-,o;A r^.^K-''; .. .. •• . •• •• 4»t «4, .. »« • ••* : :»ii'-*-'*s : »" "* >*4 * * V"a'*-;a'v-jv-a' * S»«Jt «.««J .*•••. " ' • * * ' * '^ -* "x* * * >» — -*. From the collection of the J Z ^ k Prelinger V JJibraryLi San Francisco, California 2007 San Francisco Cinematheque 1998 Program Notes San Francisco Cinematheque P.O. Box 880338 San Francisco, California 94118 Telephone: 415 822 2885 Facsimile: 415 822 1952 Email: [email protected] www.sfcineniatheque.org San Francisco Cinematheque Director Steve Anker ARTISTIC Co-Director Irina Leimbacher Interim Managing director. Spring 1998 Elise Hurwitz Administrative Manager, Spring 1998 Douglas Conrad Interim Ofhce Manager, Fall 1998 Claire Bain CURATORUL ASSISTANTS/TECHNICL\NS Thierry DiDonna Eduardo Morrell Mark Wilson Program Note Coordinator Jeff Lambert Program Note Book Producer Christine Metropoulos PROGRAM Note Editors/Contributors Steve Anker Christian Bruno Jeff Lambert Irina Leimbacher Janis Crystal Lipzin Maja Manojlovic John K. Mrozik Steve Polta Matthew Swiezynski Eric Theise Board of Directors Stefan Ferreira Cluver Sandra Peters Kerri Condron Julia Segrove-Jaurigui Elise Hurwitz Laura Takeshita Marina McDougall Program Co-Sponsors Canyon Cinema San Francisco Art Institute Headlands Center for the Arts San Francisco International Asian American Jewish Film Festival Film Festival Museum of Modem Art (New York City) San Francisco International Film Festival Pacific Film Archive Yerba Buena Center for the Arts San Francisco Cinematheque -

And the Ship Sails On

And The Ship Sails On by Serge Toubiana at the occasion of the end of his term as Director-General of the Cinémathèque française. Within just a few days, I shall come to the end of my term as Director-General of the Cinémathèque française. As of February 1st, 2016, Frédéric Bonnaud will take up the reins and assume full responsibility for this great institution. We shall have spent a great deal of time in each other's company over the past month, with a view to inducting Frédéric into the way the place works. He has been able to learn the range of our activities, meet the teams and discover all our on-going projects. This friendly transition from one director-general to the next is designed to allow Frédéric to function at full-steam from day one. The handover will have been, both in reality and in the perception, a peaceful moment in the life of the Cinémathèque, perhaps the first easy handover in its long and sometimes turbulent history. That's the way we want it - we being Costa-Gavras, chairman of our board, and the regulatory authority, represented by Fleur Pellerin, Minister of Culture and Communication, and Frédérique Bredin, Chairperson of the CNC, France's National Centre for Cinema and Animation. The peaceful nature of this handover offers further proof that the Cinémathèque has entered into a period of maturity and is now sufficiently grounded and self-confident to start out on the next chapter without trepidation. But let me step back in time. Since moving into the Frank Gehry building at 51 rue de Bercy, at the behest of the Ministry of Culture, the Cinémathèque française has undergone a profound transformation. -

22—25 Juin 2017

22—25 juin 2017 TOULOUSE MÉTROPOLE 13e festival international de littérature LE MARATHON DES MOTS SOMMAIRE Direction - Programmation : Serge Roué Direction déléguée : Dalia Hassan Coordination générale : Noémie de La Soujeole assistée de Marion Lemmet Communication : Édouard de Cazes ÉDITOS assisté de Laure Perrinet Service de presse : Shanaz Barday Olivier POIVRE DʼARVOR ........................................ 5 (Faits & Gestes - 01 53 34 64 84) Jean-Luc MOUDENC ............................................... 5 assistée de Camille Carnevale Carole DELGA ......................................................... 7 Évènements spéciaux : Elsa Viguier Coordination des bénévoles : Charlotte Barbe Philippe WAHL ......................................................... 7 assistée de Nelly Frisicaro Serge ROUÉ | Dalia HASSAN .................................. 9 Collaboration artistique : Patrick Autréaux, Laurent Belvèze, Jean-Jacques Cubaynes (Lettres occitanes) et Guillaume Poix Coordination technique : Jean-Pierre Siguier (SED Spectacles) PROGRAMME Jeudi 22 juin ............................................................................................................ 11 TOULOUSE, LE MARATHON DU LIVRE Vendredi 23 juin ................................................................................................. 23 Association Loi 1901 (Siret 481 981 165 000 30 - Code APE : 8230Z Samedi 24 juin ..................................................................................................... 43 Licences n°2-1052821 et n° 3-1052822) Dimanche