All That Divides Us

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Deadlands: Reloaded Core Rulebook

This electronic book is copyright Pinnacle Entertainment Group. Redistribution by print or by file is strictly prohibited. This pdf may be printed for personal use. The Weird West Reloaded Shane Lacy Hensley and BD Flory Savage Worlds by Shane Lacy Hensley Credits & Acknowledgements Additional Material: Simon Lucas, Paul “Wiggy” Wade-Williams, Dave Blewer, Piotr Korys Editing: Simon Lucas, Dave Blewer, Piotr Korys, Jens Rushing Cover, Layout, and Graphic Design: Aaron Acevedo, Travis Anderson, Thomas Denmark Typesetting: Simon Lucas Cartography: John Worsley Special Thanks: To Clint Black, Dave Blewer, Kirsty Crabb, Rob “Tex” Elliott, Sean Fish, John Goff, John & Christy Hopler, Aaron Isaac, Jay, Amy, and Hayden Kyle, Piotr Korys, Rob Lusk, Randy Mosiondz, Cindi Rice, Dirk Ringersma, John Frank Rosenblum, Dave Ross, Jens Rushing, Zeke Sparkes, Teller, Paul “Wiggy” Wade-Williams, Frank Uchmanowicz, and all those who helped us make the original Deadlands a premiere property. Fan Dedication: To Nick Zachariasen, Eric Avedissian, Sean Fish, and all the other Deadlands fans who have kept us honest for the last 10 years. Personal Dedication: To mom, dad, Michelle, Caden, and Ronan. Thank you for all the love and support. You are my world. B.D.’s Dedication: To my parents, for everything. Sorry this took so long. Interior Artwork: Aaron Acevedo, Travis Anderson, Chris Appel, Tom Baxa, Melissa A. Benson, Theodor Black, Peter Bradley, Brom, Heather Burton, Paul Carrick, Jim Crabtree, Thomas Denmark, Cris Dornaus, Jason Engle, Edward Fetterman, -

Finding Grace in the Concert Hall: Community and Meaning Among Springsteen Fans

FINDING GRACE IN THE CONCERT HALL: COMMUNITY AND MEANING AMONG SPRINGSTEEN FANS By LINDA RANDALL A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of WAKE FOREST UNIVERSITY On Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS In the Department of Religion December 2008 Winston Salem, North Carolina Approved By: Lynn Neal, PhD. Advisor _____________________________ Examining Committee: Jeanne Simonelli, Ph.D. Chair _____________________________ LeRhonda S. Manigault, Ph.D _____________________________ ii Acknowledgements First and foremost, my thanks go out to Drs. Neal and Simonelli for encouraging me to follow my passion and my heart. Dr. Neal helped me realize a framework within which I could explore my interests, and Dr. Simonelli kept my spirits alive so I could nurse the project along. My concert-going partner in crime, cruisin’tobruce, also deserves my gratitude, sharing expenses and experiences with me all over the eastern seaboard as well as some mid-America excursions. She tolerated me well, right up until the last time I forgot the tickets. I also must recognize the persistent assistance I received from my pal and companion Zero, my Maine Coon cat, who spent hours hanging over my keyboard as I typed. I attribute all typos and errors to his help, and thank him for the opportunity to lay the blame at his paws. And lastly, my thanks and gratitude goes out to Mr. Bruce Frederick Springsteen, a man of heart and of conscience who constantly keeps me honest and aware that “it ain’t no sin to be glad you’re alive (Badlands).” -

Maddison Barnett Dancer

3WJ+boy 167 Moore Street, Howick Auckland, New Zealand, 2014 www.3wjplusboy.co.nz MADDISON BARNETT DANCER HEIGHT: 5’6”cm EYES: GREEN HAIR: LIGHT BROWN MUSIC VIDEO CAI XUKUN ‘YOUNG’ KIEL TUTIN DRAX PROJECT ‘TOTO’ BIANCA IKINOFO PARRI$ ‘FRIDAY’ PARRIS GOEBEL SAVAGE ‘ZOOBY DOO’ PARRIS GOEBEL PSY ‘LOVE’ PARRIS GOEBEL SAM V ‘I JUST WANNA LOVE YOU’ PARRIS GOEBEL JUSTIN BIEBER ‘WHAT DO YOU MEAN’ PARRIS GOEBEL JUSTIN BIEBER ‘CHILDREN’ PARRIS GOEBEL JUSTIN BIEBER ‘SORRY’ PARRIS GOEBEL TELEVISION PRODUCE 101 CHINA DANCER - 3 MONTH CONTRACT LONG SHONG CHEN MINI REQUEST NBC’S WORLD OF DANCE (SEASON ONE) NAPPYTABS SUPER RUGBY NRL SUPER BANG BANG TVC PARRIS GOEBEL TVNZ THE PALACE SERIES CHARLOTTE PURDY REEBOX X LES MILLS LES MILLS INTERNATIONAL PROMO GANDALF ARCHER-MILLS LES MILLS ‘BODY JAM’ GANDALF ARCHER-MILLS STAGE/LIVE PERFORMANCE JOLIN TSAI UGLY BEAUTY WORLD TOUR - TAIWAN KIEL TUTIN NZX AIMS GAMES OPENING PERFORMANCE 2019 KIEL TUTIN ARMAGEDDON K-POP SHOWCASE 2019 KIEL TUTIN MOMENTUM PROD. DUALITY PRODUCTION 2018 KAYLA PAIGE THE O’NEILL TWINS CAPITAL JAMES STADIUM TOUR THE O’NEILL TWINS GOOGLE GOOGLE PRODUCT LAUNCH BIANCA IKINOFO SKYCITY DANCE TEAM NEW ZEALAND BREAKERS GAMES KAYLA PAIGE NZX AIMS GAMES OPENING PERFORMANCE 2018 KIEL TUTIN TALK2ME TE KAHA O TE RANGATAHI 2018 KYRA AOAKE THE ROYAL FAMILY CHINA TOUR 2017 PARRIS GOEBEL SORORITY DANCE 2 DANCE - SWITZERLAND KYRA AOAKE PARRI$ THE PARRI$ PROJECT’ - WORLD TOUR PARRIS GOEBEL MINI REQUEST NBC’S WORLD OF DANCE (SEASON ONE) NAPPYTABS THE ROYAL FAMILY WORLD OF DANCE GUEST PERF. 2015 PARRIS GOEBEL THE ROYAL FAMILY PARRIS GOEBEL PRESENTS: MOONCHILD PARRIS GOEBEL THE ROYAL FAMILY SKULLS AND CROWNS - U.S.A. -

Safaris to the Heart of All That Jazz

Safaris to the heart of all that jazz.... JoniMitchell.com 2014 Biography Series by Mark Scott, Part 6 of 16 In January of 1974, Joni began an extensive tour of North America with the L.A. Express, wrapping up with three concerts at the New Victoria Theatre in London, England. The final concert at the New Victoria was videotaped and an edited version was broadcast on the BBC television program The Old Grey Whistle Test in November of 1974. Larry Carlton and Joe Sample were playing with The Crusaders at the time and both opted not to go on the road with Joni and the L.A. Express. Guitarist Robben Ford replaced Larry Carlton and Larry Nash filled in for Joe Sample on piano. In a 2011 interview for JoniMitchell.com, Max Bennett said that although the pay was good for this tour, the musicians could have made more money playing gigs in L.A. and doing session work in the recording studios. Max said that the musicians loved the music, however, and that they were treated royally in every way throughout the tour. Excellent food, first class accommodations, limousines, private buses and private planes were all provided for the band’s comfort. Max also made a point of mentioning the quality of the audiences that attended the concerts. Attention was focused on the performances so completely that practically complete silence reigned in the theaters and auditoriums until after the last note of any given song was performed. For Max Bennett, “As far as tours go - I've been on several tours - this was the epitome of any great tour I've ever been on. -

Ugly Beauty: Chaucer's Poetic Ecclesiology Britta B. Rowe Ivy

Ugly Beauty: Chaucer’s Poetic Ecclesiology Britta B. Rowe Ivy, Virginia B.A., University of Virginia, 1990 M.A., University of Virginia, 2014 A Dissertation Presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of English University of Virginia August, 2017 © Copyright by Britta B. Rowe All Rights Reserved August 2017 i Abstract Over the last several decades, the “religious turn” in Chaucer studies has opened up numerous avenues for analysis of Chaucer’s poetics without completely resolving questions about their specifically Christian character, or lack thereof. Approaches to answering such questions include biographical analysis, which in Chaucer’s case seems least likely to yield substantial conclusions: we simply don’t have enough biographical data to be confident that Chaucer held strongly to one, or another, or no version of Christian faith. Our limited sources of knowledge about Chaucer’s distinctly secular professional life certainly give us no basis for confident assertions about his own personal piety. Unlike his contemporary John Lydgate, for example, Chaucer was no monk. On the other hand, given the numerous, lively and vigorous forms of lay piety in Chaucer’s era, his lack of religious vocation and/or sacerdotal ordination is not per se a limiting factor on the possibility that his poetics is robustly Christian at a deep philosophical level. One important movement of lay piety, founded on protest against ecclesial corruption, was inspired in large part by the indignation and influence of another Chaucer contemporary, John Wyclif, and this movement has been the focus of a substantial body of scholarship over the last several decades. -

Dissertation (Fan Liao)

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, IRVINE The Paradoxical Peking Opera: Performing Tradition, History, and Politics in 1949-1967 China A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Drama and Theatre by Fan Liao Committee in charge: University of California, San Diego Professor Janet L. Smarr, Chair Professor Paul G. Pickowicz, Co-Chair Professor Nancy A. Guy Professor Marianne McDonald Professor John S. Rouse University of California, Irvine Professor Stephen Barker 2012 The Dissertation of Fan Liao is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: Co-Chair Chair University of California, San Diego University of California, Irvine 2012 iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page……………………………………………………………………………iii Table of Contents……………………………………………………………....................iv Vita………………………………………………………………………………………...v Abstract…………………………………………………………………………………...vi Introduction………………………………………………………………………………..1 Chapter One………………………………………….......................................................29 Reform of Jingju Old Repertoire in the 1950s Chapter Two……………………………………………………………………………...81 Making History: The Creation of New Jingju Historical Plays Chapter Three…………………………………………………………………………...135 Inventing Traditions: The Creation of New Jingju Plays with Contemporary Themes Conclusion……………………………………………………………………………...204 Appendix……………………………………………………………………………….211 Bibliography……………………………………………………………………………229 iv VITA 2003 -

A Knickerbocker Tour of New York State, 1822: "Our Travels, Statistical

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Electronic Texts in American Studies Libraries at University of Nebraska-Lincoln 1822 A Knickerbocker tour of New York State, 1822: "Our Travels, Statistical, Geographical, Mineorological, Geological, Historical, Political and Quizzical"; Written by Myself XYZ etc. Johnston Verplanck New York American Louis Leonard Tucker , editor The New York State Library Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/etas Part of the American Studies Commons Verplanck, Johnston and Tucker, Louis Leonard , editor, "A Knickerbocker tour of New York State, 1822: "Our Travels, Statistical, Geographical, Mineorological, Geological, Historical, Political and Quizzical"; Written by Myself XYZ etc." (1822). Electronic Texts in American Studies. 61. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/etas/61 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Libraries at University of Nebraska-Lincoln at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Texts in American Studies by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. I iC 1\ N A D I I I 0 iI I' I ~ I A Knickerbocker tour of New York State, 1822 ~~Our Travels, Statistical, Geographical, Mineorological, Geological, Historical, Political and "Quizzical" Written by myself XYZ etc. Edited, with an Introduction and Notes, By LoUIS LEONARD TUCKER The University of the State of New York The State Education Department The New York State Library Albany 1968 THE UNIVERSITY OF THE STATE OF NEW YORK Regents of the University (with years when terms expire) 1969 JOSEPH W. MCGOVERN, A.B., LL.B., L.H.D., LL.D., Chancellor · New York 1970 EVERETT J. -

Kiel Tutin Resume

KIEL TUTIN CHOREOGRAPHER MUSIC VIDEO TWICE ‘I CAN’T STOP ME’ CHOREOGRAPHER LEE SUHYUN ‘ALIEN’ CHOREOGRAPHER BLACKPINK ‘LOVESICK GIRLS’ CHOREOGRAPHER JUUN D ‘ANH LA GA NGOC’ CHOREOGRAPHER RAINIE YANG ‘BAD BAD LADY’ CHOREOGRAPHER BLACKPINK & SELENA GOMEZ ‘ICE CREAM’ CHOREOGRAPHER ITZY ‘NOT SHY’ CHOREOGRAPHER J.Y.PARK ‘WHEN WE DISCO’ CHOREOGRAPHER HYUNA ‘GOOD GIRL’ CHOREOGRAPHER SOMI ‘WHAT YOU WAITING FOR’ CHOREOGRAPHER BLACKPINK ‘HOW YOU LIKE THAT’ CHOREOGRAPHER R1SE ‘SUNR1SE’ CHOREOGRAPHER NIZI ‘MAKE YOU HAPPY’ CHOREOGRAPHER TWICE ‘FANFARE’ CHOREOGRAPHER TWICE ‘MORE & MORE’ CHOREOGRAPHER HAILEE STEINFELD ‘I LOVE YOU’S' CHOREOGRAPHER ZHANG BICHEN (DIAMOND) ‘MY WAY’ CHOREOGRAPHER COCO LEE ‘FANCY’ CHOREOGRAPHER TODRICK HALL ‘FAG’ CHOREOGRAPHER TWICE ‘FEEL SPECIAL’ CHOREOGRAPHER KUN ‘YOUNG’ CHOREOGRAPHER SOMI ‘BIRTHDAY’ CHOREOGRAPHER TWICE ‘FANCY’ CHOREOGRAPHER BLACKPINK ‘KILL THIS LOVE’ CHOREOGRAPHER AMANDA ‘NEW DAY’ CHOREOGRAPHER R.TEE X ANDA ‘WHAT YOU WAITING FOR’ CHOREOGRAPHER AMANDA ‘UTOPIA’ CHOREOGRAPHER JOLIN TSAI ‘WOMXNLY (DANCE VERSION’ CHOREOGRAPHER JOLIN TSAI ‘UGLY BEAUTY’ CHOREOGRAPHER JENNIE (FROM BLACKPINK) ‘SOLO’ CHOREOGRAPHER BLACKPINK ‘DDU-DU DDU-DU’ CHOREOGRAPHER JENNIFER LOPEZ ‘DINERO (FEAT. CARDI B) CHOREOGRAPHER JENNIFER LOPEZ ‘EL ANILLO’ CHOREOGRAPHER JOLIN TSAI ‘STAND UP’ CHOREOGRAPHER MONSTA X ‘SPOTLIGHT’ CHOREOGRAPHER ANNA ‘TIPTOE’ CHOREOGRAPHER ANNA ‘E-HUH?’ CHOREOGRAPHER ANNA ‘PARTY CRASHER’ CHOREOGRAPHER STAN WALKER ‘YOU NEVER KNOW’ CHOREOGRAPHER iKON ‘BOUNCE (RHYTHM TA)’ CO-CHOREOGRAPHER CL ‘HELLO BITCHES’ AS. CHOREOGRAPHER PSY ‘DADDY’ CO-CHOREOGRAPHER G-DRAGON & T.O.P ‘ZUTTER’ AS. CHOREOGRAPHER BIGBANG ‘BANG BANG BANG’ AS. CHOREOGRAPHER JOLIN TSAI ‘MEDUSA’ CHOREOGRAPHER JOLIN TSAI ‘PLAY’ CHOREOGRAPHER JOLIN TSAI ‘PHONY QUEEN’ CHOREOGRAPHER 4MINUTE ‘CRAZY’ CHOREOGRAPHER TOURS JOLIN TSAI ‘UGLY BEAUTY WORLD TOUR’ CHOREOGRAPHER TODRICK HALL ‘HAUS PARTY WORLD TOUR’ CHOREOGRAPHER COCO LEE ‘ME TO YOU’ TOUR CHOREOGRAPHER JENNIFER LOPEZ ‘IT’S MY PARTY’ U.S.A. -

Evaluating Cultural Landscape Remediation Design Based on VR Technology

International Journal of Geo-Information Article Evaluating Cultural Landscape Remediation Design Based on VR Technology Zhengsong Lin 1, Lu Zhang 2, Su Tang 3, Yang Song 4 and Xinyue Ye 4,* 1 School of Art and Design, Wuhan Institute of Technology, Wuhan 430205, China; [email protected] 2 School of Arts Communication, China University of Geosciences, Wuhan 430074, China; [email protected] 3 Foreign Language Department, Wuhan Huaxia University of Technology, Wuhan 430223, China; [email protected] 4 Department of Landscape Architecture and Urban Planning, Texas A & M University, College Station, TX 77840, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Due to the recent excessive pursuit of rapid economic development in China, the cultural heritage resources have been gradually destroyed. This paper proposes cultural recovery and ecological remediation patterns, and adopts virtual reality (VR) technology to evaluate the visual aesthetic effect of the restored landscape. The results show that: (1) the average vegetation coverage increased, providing data support for remediation design evaluation; and (2) the fixation counts and average saccade counts of the subjects increased after the remediation design, indicating that the restored cultural landscape reduced visual fatigue and provided a better visual aesthetic experience. Furthermore, the comparative analysis of the quality of the water environment shows that the remediation design project improved the ecological environment quality of the relics area. The results Citation: Lin, Z.; Zhang, L.; Tang, S.; of this study will contribute to rural revitalization in minority areas in southwest China. Song, Y.; Ye, X. Evaluating Cultural Landscape Remediation Design Keywords: VR technology; visual aesthetic experience; ecological remediation evaluation; Tujia Based on VR Technology. -

Tour Essentials

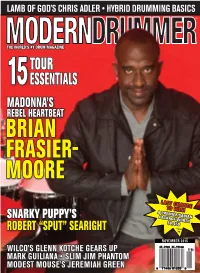

LAMB OF GOD’S CHRIS ADLER • HYBRID DRUMMING BASICS THE WORLD’S #1 DRUM MAGAZINE TOUR 15 ESSENTIALS MADONNA’S REBEL HEARTBEAT BRIAN FRASIER- MOORE LAST CHANCE TO WIN! A PREMIER/SABIAN SNARKY PUPPY’S PACKAGE WORTH $6,450 Page ROBERT “SPUT” SEARIGHT 75 NOVEMBER 2015 WILCO’S GLENN KOTCHE GEARS UP MARK GUILIANA • SLIM JIM PHANTOM MODEST MOUSE’S JEREMIAH GREEN 12 Modern Drummer June 2014 June 2014 Modern Drummer 1 THE ULTIMATE DRUM MIC PACK, FROM THE INNOVATORS The Audix DP7 Drum Pack is the standard for capturing the unique sound of your drums in studio and for live sound. The DP7 is jam packed with our popular D6 for kick drum, an i5 mic for snare, two D2s for rack toms, a D4 for the floor tom and two ADX51s for overhead miking. With a sleek, foam-lined aluminum case to keep the mics safe, the DP7 is truly everything a drummer needs in a single package. DP7 Photo of Anthony Jones, Pink Martini www.audixusa.com 503.682.6933 ©2015 Audix Corporation All Rights Reserved. Audix and the Audix Logo are trademarks of Audix Corporation. 2 Modern Drummer June 2014 PROUD PROUD DW Proud Ad - Josh F - FULL (MD).indd 1 7/16/15 11:30 AM VICFIRTH.COM VICFIRTH.COM ©2015 Vic Firth Company ©2015 outside the box designs. outside the box sounds. Introducing the new Vic Firth Split Brush Let’s face it. Your sticks can’t do everything. Next-level music requires next-level thinking. That’s why we’re constantly collaborating with the world’s top players to create fresh sounds and take your music to new places. -

Inheritance and Innovation in the Process of Artistic Creation in Major Kunqu Productions in the People‘S Republic of China, 2001-2015

RETURN OF THE SOUL: INHERITANCE AND INNOVATION IN THE PROCESS OF ARTISTIC CREATION IN MAJOR KUNQU PRODUCTIONS IN THE PEOPLE‘S REPUBLIC OF CHINA, 2001-2015 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‗I AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN THEATRE OCTOBER 2019 By Ming Yang Dissertation Committee: Elizabeth A. Wichmann-Walczak, Chairperson Julie A. Iezzi Kirstin A. Pauka Cathryn H. Clayton Kate A. Lingley Chin-Tang Lo, Ex-Officio Keywords: Kunqu, inheritance, innovation, literature, performance, production I © 2019, Ming Yang II ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This dissertation would not have been possible without the support of individuals and institutions dedicated to the studies of Chinese theatre and Chinese culture. I wish to express my most sincere gratitude to the Kunqu and Xiqu artists and scholars who granted me interviews, shared with me their knowledge and experience, and offered their insights on this dissertation. I am grateful to the administrators at the Northern Kunqu Opera Theatre, the Shanghai Kunqu Troupe, the Kunju Theatre of the Jiangsu Performing Arts Group Co., LTD, and the Suzhou Kunju Troupe for allowing me to observe their rehearsals and performances and for their help in introducing me to artists on the creative teams of productions in this research. I would also like to acknowledge the following institutions for their financial support: the Asian Cultural Council and the Ah Kin (Buck) Yee Graduate Fellowship in Chinese Studies for their fellowships to help me initiate my study at the University of Hawai‗i at Mānoa; the John Young Scholarship in the Arts and the East-West Center Degree Fellowship for further supporting it; the UH-Beida (Peking/Beijing University) Exchange Program Award for the opportunity to conduct eleven months of field research in China; the East-West Center Field Research Fund for supporting the field research; and the Chun Ku and Soo Yong Huang Foundation Scholarship in Chinese Studies, the Faith C. -

Beauty and Skin Color Hierarchy in the Philippines and the US

Colonial Faces: Beauty and Skin Color Hierarchy in the Philippines and the U.S. By Joanne Laxamana Rondilla A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Ethnic Studies in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Catherine Ceniza Choy, Chair Professor Patricia Penn Hilden Professor Abigail De Kosnik Professor Margaret Hunter Fall 2012 Copyright © 2012 Joanne Laxamana Rondilla All rights reserved Abstract Colonial Faces: Beauty and Skin Color Hierarchy in the Philippines and the U.S. by Joanne Laxamana Rondilla Doctor of Philosophy in Ethnic Studies University of California, Berkeley Professor Catherine Ceniza Choy, Chair “Colonial Faces: Beauty and Skin Color Hierarchy in the Philippines and the U.S.” investigates how perceptions of beauty, skin color hierarchy, the globalization of beauty standards, and the ongoing colonial relationship between the Philippines and the U.S. are related. This project takes a transnational approach in order to compare beauty and skin color hierarchy among Filipinas in the Philippines and in the diaspora. It examines how beauty standards are constructed locally and globally, and how Filipino women in the Philippines and the U.S. respond to these standards. It addresses the popularity of skin-lightening products in the Philippines and looks at how Filipino American women are affected by this practice. This project also explores how skin-lightening products are marketed and analyzes the role of mixed-race models in this marketing. 1 To my sisters. For our daughters. i Table of Contents Abstract Dedication Table of Contents List of Figures Acknowledgments Chapter 1: Introduction Research Questions and Methodology Situating the Conversation The Chapters at a Glance Chapter 2: Skin Color Hierarchy in the Philippines and the U.S.