Transformations of Identity and Society in Essex, C.AD 400-1066

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Research Framework Revised.Vp

Frontispiece: the Norfolk Rapid Coastal Zone Assessment Survey team recording timbers and ballast from the wreck of The Sheraton on Hunstanton beach, with Hunstanton cliffs and lighthouse in the background. Photo: David Robertson, copyright NAU Archaeology Research and Archaeology Revisited: a revised framework for the East of England edited by Maria Medlycott East Anglian Archaeology Occasional Paper No.24, 2011 ALGAO East of England EAST ANGLIAN ARCHAEOLOGY OCCASIONAL PAPER NO.24 Published by Association of Local Government Archaeological Officers East of England http://www.algao.org.uk/cttees/Regions Editor: David Gurney EAA Managing Editor: Jenny Glazebrook Editorial Board: Brian Ayers, Director, The Butrint Foundation Owen Bedwin, Head of Historic Environment, Essex County Council Stewart Bryant, Head of Historic Environment, Hertfordshire County Council Will Fletcher, English Heritage Kasia Gdaniec, Historic Environment, Cambridgeshire County Council David Gurney, Historic Environment Manager, Norfolk County Council Debbie Priddy, English Heritage Adrian Tindall, Archaeological Consultant Keith Wade, Archaeological Service Manager, Suffolk County Council Set in Times Roman by Jenny Glazebrook using Corel Ventura™ Printed by Henry Ling Limited, The Dorset Press © ALGAO East of England ISBN 978 0 9510695 6 1 This Research Framework was published with the aid of funding from English Heritage East Anglian Archaeology was established in 1975 by the Scole Committee for Archaeology in East Anglia. The scope of the series expanded to include all six eastern counties and responsi- bility for publication passed in 2002 to the Association of Local Government Archaeological Officers, East of England (ALGAO East). Cover illustration: The excavation of prehistoric burial monuments at Hanson’s Needingworth Quarry at Over, Cambridgeshire, by Cambridge Archaeological Unit in 2008. -

Great Totham Parish

Great Totham Parish Magazine sent to every home in Great Totham April 2019 Easter Services at St. Peter’s Church Maundy Thursday 18th April 7:30pm until 9pm Eucharist of the Last Supper followed by Prayer Watch Good Friday 19th April 2pm Stations of the Cross Easter Day 21st April 6am Dawn Eucharist 8am Morning Prayer 10am Family Communion All Welcome Inside This Edition: Looking forward to Easter Children’s Activities 2 Sunday (see page 10 for details) 8am Holy Communion (Prayerbook) or Morning Prayer 10am Parish Communion or Service of the Word (with Sunday Club for children) 6pm Evensong Choir Practice Mondays 10.30 am Senior Citizens Lunch Club Tuesdays in the Honywood Hall 11am Study & Discussion Wednesdays 10.30am at Honywood Hall Thursday 10.30am Edward Bear Club (Toddler Service, followed by coffee and play) Parish Contacts: Mother’s Union During the Interregnum 4th Friday of each month, 1.45pm for all church matters please Bell-ringing Practice contact: Fridays at 7.45 pm Associate Priest Rev’d Sue Godsmark : 01621 891513 Email : [email protected] If you are unable to contact the Associate Priest please speak to the Churchwardens Churchwardens Isobel Doubleday : 01621 891329 Karen Tarpey : 01621 892122 Baptism Co-ordinator Janet Gleghorn : 01621 892746 Magazine: Enquiries : Helen Mutton : 01621 891067 Adverts : Pauline Stebbing : 01621 892059 Email : [email protected] Website: www.essexinfo.net/st-peter-s-church-great-totham 3 Church News Dedication of Communion Wine Vessels Earlier this year, a glass communion wine vessel was broken and a replacement was proving difficult (impossible) to find. -

ADDENDUM to UTT/ 13/3123/FUL (STRETHALL) (Referred To

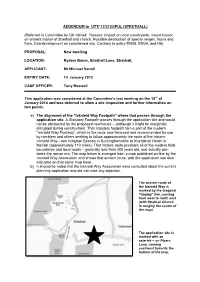

ADDENDUM to UTT/ 13/3123/FUL (STRETHALL) (Referred to Committee by Cllr Menell. Reason: Impact on local countryside, visual impact on ancient manor of Strethall and church. Possible destruction of special verges, fauna and flora. Overdevelopment on constrained site. Contrary to policy ENV8, ENV9, and H6) PROPOSAL: New dwelling LOCATION: Ryders Barns, Strethall Lane, Strethall, APPLICANT: Mr Michael Vanoli EXPIRY DATE: 14 January 2013 CASE OFFICER: Tony Boswell This application was considered at the Committee’s last meeting on the 15th of January 2014 and was deferred to allow a site inspection and further information on two points. a) The alignment of the “Icknield Way Footpath” where that passes through the application site. A Statutory Footpath passes through the application site and would not be obstructed by the proposed new house – (although it might be marginally disrupted during construction). That statutory footpath forms part of the modern “Icknield Way Footway”, which is the route now favoured and recommended for use by ramblers and others seeking to follow approximately the route of the historic Icknield Way - rom Ivinghoe Beacon in Buckinghamshire to Knettishall Heath in Norfolk (approximately 110 miles). That historic route predates all of the modern field boundaries and local roads – generally less than 300 years old, and actually pre- dates the roman era. The map below is enlarged from a map published on-line by the Icknield Way Association and shows that ancient route, with the application site also indicated on that same map base. b) It should be noted that the Icknield Way Association were consulted about the current planning application and did not raise any objection. -

Reading History in Early Modern England

READING HISTORY IN EARLY MODERN ENGLAND D. R. WOOLF published by the press syndicate of the university of cambridge The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge, United Kingdom cambridge university press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge CB2 2RU, UK www.cup.cam.ac.uk 40 West 20th Street, New York, NY 10011–4211, USA www.cup.org 10 Stamford Road, Oakleigh, Melbourne 3166, Australia Ruiz de Alarco´n 13, 28014 Madrid, Spain © Cambridge University Press 2000 This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published 2000 Printed in the United Kingdom at the University Press, Cambridge Typeset in Sabon 10/12pt [vn] A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloguing in Publication data Woolf, D. R. (Daniel R.) Reading History in early modern England / by D. R. Woolf. p. cm. (Cambridge studies in early modern British history) ISBN 0 521 78046 2 (hardback) 1. Great Britain – Historiography. 2. Great Britain – History – Tudors, 1485–1603 – Historiography. 3. Great Britain – History – Stuarts, 1603–1714 – Historiography. 4. Historiography – Great Britain – History – 16th century. 5. Historiography – Great Britain – History – 17th century. 6. Books and reading – England – History – 16th century. 7. Books and reading – England – History – 17th century. 8. History publishing – Great Britain – History. I. Title. II. Series. DA1.W665 2000 941'.007'2 – dc21 00-023593 ISBN 0 521 78046 2 hardback CONTENTS List of illustrations page vii Preface xi List of abbreviations and note on the text xv Introduction 1 1 The death of the chronicle 11 2 The contexts and purposes of history reading 79 3 The ownership of historical works 132 4 Borrowing and lending 168 5 Clio unbound and bound 203 6 Marketing history 255 7 Conclusion 318 Appendix A A bookseller’s inventory in history books, ca. -

History of the Welles Family in England

HISTORY OFHE T WELLES F AMILY IN E NGLAND; WITH T HEIR DERIVATION IN THIS COUNTRY FROM GOVERNOR THOMAS WELLES, OF CONNECTICUT. By A LBERT WELLES, PRESIDENT O P THE AMERICAN COLLEGE OP HERALDRY AND GENBALOGICAL REGISTRY OP NEW YORK. (ASSISTED B Y H. H. CLEMENTS, ESQ.) BJHttl)n a account of tljt Wu\\t% JFamtlg fn fHassssacIjusrtta, By H ENRY WINTHROP SARGENT, OP B OSTON. BOSTON: P RESS OF JOHN WILSON AND SON. 1874. II )2 < 7-'/ < INTRODUCTION. ^/^Sn i Chronology, so in Genealogy there are certain landmarks. Thus,n i France, to trace back to Charlemagne is the desideratum ; in England, to the Norman Con quest; and in the New England States, to the Puri tans, or first settlement of the country. The origin of but few nations or individuals can be precisely traced or ascertained. " The lapse of ages is inces santly thickening the veil which is spread over remote objects and events. The light becomes fainter as we proceed, the objects more obscure and uncertain, until Time at length spreads her sable mantle over them, and we behold them no more." Its i stated, among the librarians and officers of historical institutions in the Eastern States, that not two per cent of the inquirers succeed in establishing the connection between their ancestors here and the family abroad. Most of the emigrants 2 I NTROD UCTION. fled f rom religious persecution, and, instead of pro mulgating their derivation or history, rather sup pressed all knowledge of it, so that their descendants had no direct traditions. On this account it be comes almost necessary to give the descendants separately of each of the original emigrants to this country, with a general account of the family abroad, as far as it can be learned from history, without trusting too much to tradition, which however is often the only source of information on these matters. -

Beowulf and the Sutton Hoo Ship Burial

Beowulf and The Sutton Hoo Ship Burial The value of Beowulf as a window on Iron Age society in the North Atlantic was dramatically confirmed by the discovery of the Sutton Hoo ship-burial in 1939. Ne hÿrde ic cymlīcor cēol gegyrwan This is identified as the tomb of Raedwold, the Christian King of Anglia who died in hilde-wæpnum ond heaðo-wædum, 475 a.d. – about the time when it is thought that Beowulf was composed. The billum ond byrnum; [...] discovery of so much martial equipment and so many personal adornments I never yet heard of a comelier ship proved that Anglo-Saxon society was much more complex and advanced than better supplied with battle-weapons, previously imagined. Clearly its leaders had considerable wealth at their disposal – body-armour, swords and spears … both economic and cultural. And don’t you just love his natty little moustache? xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx(Beowulf, ll.38-40.) Beowulf at the movies - 2007 Part of the treasure discovered in a ship-burial of c.500 at Sutton Hoo in East Anglia – excavated in 1939. th The Sutton Hoo ship and a modern reconstruction Ornate 5 -century head-casque of King Raedwold of Anglia Caedmon’s Creation Hymn (c.658-680 a.d.) Caedmon’s poem was transcribed in Latin by the Venerable Bede in his Ecclesiatical History of the English People, the chief prose work of the age of King Alfred and completed in 731, Bede relates that Caedmon was an illiterate shepherd who composed his hymns after he received a command to do so from a mysterious ‘man’ (or angel) who appeared to him in his sleep. -

75 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

75 bus time schedule & line map 75 Colchester Town Centre View In Website Mode The 75 bus line (Colchester Town Centre) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Colchester Town Centre: 6:41 AM - 8:15 PM (2) Maldon: 6:08 AM - 7:20 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 75 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 75 bus arriving. Direction: Colchester Town Centre 75 bus Time Schedule 64 stops Colchester Town Centre Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday Not Operational Morrisons Wycke Hill, Maldon Tuesday 6:41 AM - 8:15 PM Randolph Close, Maldon 1 Randolph Close, Maldon Civil Parish Wednesday 6:41 AM - 8:15 PM Lambourne Grove, Maldon Thursday 6:41 AM - 8:15 PM 155 Fambridge Road, Maldon Civil Parish Friday 6:41 AM - 8:15 PM Milton Road, Maldon Saturday 7:15 AM - 8:20 PM 1 Milton Road, Maldon Civil Parish Shakespeare Drive, Maldon 23 Shakespeare Drive, Maldon Civil Parish 75 bus Info Rydal Drive, Maldon Direction: Colchester Town Centre 1 Kestrel Mews, Maldon Civil Parish Stops: 64 Trip Duration: 63 min Blackwater Leisure Centre, Maldon Line Summary: Morrisons Wycke Hill, Maldon, 3 Tideway, Maldon Civil Parish Randolph Close, Maldon, Lambourne Grove, Maldon, Milton Road, Maldon, Shakespeare Drive, Maldon, Jersey Road, Maldon Rydal Drive, Maldon, Blackwater Leisure Centre, 31 Park Drive, Maldon Civil Parish Maldon, Jersey Road, Maldon, Meadway, Maldon, Berridge House, Maldon, Victoria Road, Maldon, The Meadway, Maldon Swan Hotel, Maldon Town Centre, Tesco Store, 16 Park Drive, -

GT.TOTHAM MAG - Nov 19 Final

2 Sunday (see page 10 for details) 8am Holy Communion (Prayerbook) or Morning Prayer 10am Parish Communion or Service of the Word (with Sunday Club for children) 6pm Evensong Choir Practice Mondays 10.30 am Senior Citizens Lunch Club Tuesdays in the Honywood Hall 11am Study & Discussion Wednesdays 10.30am at Honywood Hall Thursday 10.30am Edward Bear Club (Toddler Service, followed by coffee and play) Parish Contacts: Mother’s Union 4th Friday of each month, 1.45pm During the Interregnum for all church matters please Bell-ringing Practice contact: Fridays at 7.45 pm Associate Priest Rev’d Sue Godsmark : 01621 891513 Email : [email protected] If you are unable to contact the Associate Priest please speak to the Churchwardens: Churchwardens Isobel Doubleday : 01621 891329 Karen Tarpey : 01621 892122 Baptisms For enquiries about baptisms, please contact Rev’d Sue Godsmark. Magazine: Enquiries : Helen Mutton : 01621 891067 Adverts : Pauline Stebbing : 01621 892059 Email : [email protected] Website: www.achurchnearyou.com/church/6657 3 Church News Pets Welcome Service A variety of pets, large and small (or a photo), were welcomed at our churchyard service of thanksgiving on 22nd September, when we were blessed with fine weather. Light refreshments were served after the service. 4 Church News Harvest Festival We celebrated Harvest on 29th September this year. The church was beautifully decorated (thanks to all who helped) and offerings of food were brought to the altar for donation to the Maldon Food Bank. A delicious lunch was shared after the service. October Sunday Club Activities 5 Church News Meet Rev’d Tracey Harvey Hi, my name is Rev’d Tracey Harvey. -

Essex, Where It Remains to This Day, the Oldest Friends' School in the United Kingdom

The Journal of the Friends Historical Society Volume 60 Number 2 CONTENTS page 75-76 Editorial 77-96 Presidential Address: The Significance of the Tradition: Reflections on the Writing of Quaker History. John Punshon 97-106 A Seventeenth Century Friend on the Bench The Testimony of Elizabeth Walmsley Diana Morrison-Smith 107-112 The Historical Importance of Jordans Meeting House Sue Smithson and Hilary Finder 113-142 Charlotte Fell Smith, Friend, Biographer and Editor W Raymond Powell 143-151 Recent Publications 152 Biographies 153 Errata FRIENDS HISTORICAL SOCIETY President: 2004 John Punshon Clerk: Patricia R Sparks Membership Secretary/ Treasurer: Brian Hawkins Editor of the Journal Howard F. Gregg Annual membership Subscription due 1st January (personal, Meetings and Quaker Institutions in Great Britain and Ireland) raised in 2004 to £12 US $24 and to £20 or $40 for other institutional members. Subscriptions should be paid to Brian Hawkins, Membership Secretary, Friends Historical Society, 12 Purbeck Heights, Belle Vue Road, Swanage, Dorset BH19 2HP. Orders for single numbers and back issues should be sent to FHS c/o the Library, Friends House, 173 Euston Road, London NW1 2BJ. Volume 60 Number 2 2004 (Issued 2005) THE JOURNAL OF THE FRIENDS HISTORICAL SOCIETY Communications should be addressed to the Editor of the Journal c/o 6 Kenlay Close, New Earswick, York YO32 4DW, U.K. Reviews: please communicate with the Assistant Editor, David Sox, 20 The Vineyard, Richmond-upon-Thames, Surrey TW10 6AN EDITORIAL The Editor apologises to contributors and readers for the delayed appearance of this issue. Volume 60, No 2 begins with John Punshon's stimulating Presidential Address, exploring the nature of historical inquiry and historical writing, with specific emphasis on Quaker history, and some challenging insights in his text. -

Redeeming Beowulf and Byrhtnoth

Redeeming Beowulf: The Heroic Idiom as Marker of Quality in Old English Poetry Abstract: Although it has been fashionable lately to read Old English poetry as being critical of the values of heroic culture, the heroic idiom is the main, and perhaps the only, marker of quality in Old English poetry. Considering in turn the ‘sacred heroic’ in Genesis A and Andreas, the ‘mock heroic’ in Judith and Riddle 51, and the fiercely debated status of Byrhtnoth and Beowulf in The Battle of Maldon and Beowulf, this discussion suggests that modern scholarship has confused the measure with the measured. Although an uncritical heroic idiom may not be to modern critical tastes, it is suggested here that the variety of ways in which the heroic idiom is used to evaluate and mark value demonstrates the flexibility and depth of insight achieved by Old English poets through their apparently limited subject matter. A hero can only be defined by a narrative in which he or she meets or exceeds measures set by society—in which he or she demonstrates his or her quality. In that sense, all heroic narratives are narratives about quality. In Old English poetry, the heroic idiom stands as the marker of quality for a wide range of things: people, artefacts, actions, and events that are good, respected, desirable, and valued are marked by being presented with the characteristic language and ethic of an idealised, archaic warrior-culture.1 This is not, of course, a new point; it is traditional in Old English scholarship to associate quality with the elite, military world of generous war-lords, loyal thegns, gorgeous equipment, great acts of courage, and 1 The characteristic subject matter and style of Old English poetry is referred to in varying ways by critics. -

Profile for the Parishes Of

Profile for the Parishes of St. Nicholas with St Mary’s Great Wakering Foulness and All Saints with St Mary’s Barling Magna Little Wakering The Profile for the Parishes of Great Wakering with Foulness Island and Barling Magna with Little Wakering 1.0 INTRODUCTION The Priest-in-Charge of our parishes since 2008 has recently assumed the additional role of Priest-in-Charge of the nearby parish of St Andrews Rochford with Sutton and Shopland and taken up residence in the Rochford Rectory. We are looking for an Associate Priest and Team Vicar designate to live in the Great Wakering Vicarage and to work with our Priest-in-charge in the care, support and development of all the parishes. This is a response to the ‘Re-imagining Ministry’ document passed by the Diocesan Synod in March 2013. Our Parishes are close to Shoeburyness and Southend-on-sea. Both have good rail links to London, which is about an hour away and used by commuters. Shoeburyness has the historic Shoebury Garrison, now vacated by the army and re-developed as a residential village which retains the original character. Shoeburyness also has two popular beach areas for bathing, walking or water sports. There are a number of shops and businesses and an Asda supermarket which is served by a bus from Great Wakering. Southend-on Sea is the nearest town. It has two commuter rail lines and an expanding airport. It has the usual High Street stores and new library and university buildings in the town centre. Its long pier is a local attraction and renowned as the longest pleasure pier in the world. -

The Last Kingdom

PRESS RELEASE THE LAST KINGDOM A CARNIVAL FILMS & BBC AMERICA co-production for BBC TWO An adaptation of Bernard Cornwell’s best-selling series of books by BAFTA nominated and RTS award-winning writer Stephen Butchard The Last Kingdom, a new historical 8x60 drama series launches on BBC Two and BBC America in October. Made by Carnival Films, the Golden Globe® and Emmy® award- winning producers of Downton Abbey, the show airs on BBC America on 10 October, 2015 and later the same month on BBC Two. BAFTA nominated and RTS award-winning writer Stephen Butchard, (Good Cop, Five Daughters, House of Saddam), has adapted Bernard Cornwell’s best-selling franchise “The Saxon Stories” for the screen. Cornwell is also known for his much-loved “Sharpe” novels that became the long- running TV series of the same name starring Sean Bean. The series cast is headed up by Alexander Dreymon (American Horror Story, Blood Ransom), playing Uhtred of Bebbanburg, with Emily Cox (Homeland) as Brida, Rutger Hauer (Blade Runner, Galavant) as Ravn, Matthew Macfadyen (The Enfield Haunting, Ripper Street) as Lord Uhtred, David Dawson (Peaky Blinders) as Alfred, Rune Temte (Eddie the Eagle) as Ubba, Ian Hart (Boardwalk Empire) as Beocca and Adrian Bower (Mount Pleasant) as Leofic. Set in the year 872, when many of the separate kingdoms of what we now know as England have fallen to the invading Vikings, the great kingdom of Wessex has been left standing alone and defiant under the command of King Alfred the Great. Against this turbulent backdrop lives our hero, Uhtred.