The Philippines: Breakthrough in Mindanao

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court Professor Herminio Harry L

The PHILJA Judicial Journal The PHILJA Judicial Journal is published twice a year by the Research, Publications and Linkages Office of the Philippine Judicial Academy (PHILJA). The Journal features articles, lectures, research outputs and other materials of interest to members of the Judiciary, particularly judges, as well as law students and practitioners. The views expressed by the authors do not necessarily reflect the views of either the Academy or its editorial board. Editorial and general offices are located at PHILJA, 3rd Floor, Centennial Building, Supreme Court, Padre Faura Street, Manila. Tel. No.: 552-9524 Telefax No.: 552-9628 Email: [email protected]; [email protected] CONTRIBUTIONS. The PHILJA Judicial Journal invites contributions. Please include author’s name and biographical information. The editorial board reserves the right to edit the materials submitted for publication. Copyright © 2012 by The PHILJA Judicial Journal. All rights reserved. For more information, please visit the PHILJA website at http://philja.judiciary.gov.ph. ISSN 2244-5854 SUPREME COURT OF THE PHILIPPINES CHIEF JUSTICE Hon. MARIA LOURDES P. A. SERENO ASSOCIATE JUSTICES Hon. ANTONIO T. CARPIO Hon. PRESBITERO J. VELASCO, Jr. Hon. TERESITA J. LEONARDO-DE CASTRO Hon. ARTURO D. BRION Hon. DIOSDADO M. PERALTA Hon. LUCAS P. BERSAMIN Hon. MARIANO C. DEL CASTILLO Hon. ROBERTO A. ABAD Hon. MARTIN S. VILLARAMA, Jr. Hon. JOSE P. PEREZ Hon. JOSE C. MENDOZA Hon. BIENVENIDO L. REYES Hon. ESTELA M. PERLAS-BERNABE Hon. MARVIC MARIO VICTOR F. LEONEN COURT ADMINISTRATOR Hon. JOSE MIDAS P. MARQUEZ DEPUTY COURT ADMINISTRATORS Hon. RAUL B. VILLANUEVA Hon. ANTONIO M. EUGENIO, Jr. -

Between Rhetoric and Reality: the Progress of Reforms Under the Benigno S. Aquino Administration

Acknowledgement I would like to extend my deepest gratitude, first, to the Institute of Developing Economies-JETRO, for having given me six months from September, 2011 to review, reflect and record my findings on the concern of the study. IDE-JETRO has been a most ideal site for this endeavor and I express my thanks for Executive Vice President Toyojiro Maruya and the Director of the International Exchange and Training Department, Mr. Hiroshi Sato. At IDE, I had many opportunities to exchange views as well as pleasantries with my counterpart, Takeshi Kawanaka. I thank Dr. Kawanaka for the constant support throughout the duration of my fellowship. My stay in IDE has also been facilitated by the continuous assistance of the “dynamic duo” of Takao Tsuneishi and Kenji Murasaki. The level of responsiveness of these two, from the days when we were corresponding before my arrival in Japan to the last days of my stay in IDE, is beyond compare. I have also had the opportunity to build friendships with IDE Researchers, from Nobuhiro Aizawa who I met in another part of the world two in 2009, to Izumi Chibana, one of three people that I could talk to in Filipino, the other two being Takeshi and IDE Researcher, Velle Atienza. Maraming salamat sa inyo! I have also enjoyed the company of a number of other IDE researchers within or beyond the confines of the Institute—Khoo Boo Teik, Kaoru Murakami, Hiroshi Kuwamori, and Sanae Suzuki. I have been privilege to meet researchers from other disciplines or area studies, Masashi Nakamura, Kozo Kunimune, Tatsufumi Yamagata, Yasushi Hazama, Housan Darwisha, Shozo Sakata, Tomohiro Machikita, Kenmei Tsubota, Ryoichi Hisasue, Hitoshi Suzuki, Shinichi Shigetomi, and Tsuruyo Funatsu. -

Reproductive Health Bill

Reproductive Health Bill From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Intrauterine device (IUD): The Reproductive Health Bill provides for universal distribution of family planning devices, and its enforcement. The Reproductive Health bills, popularly known as the RH Bill , are Philippine bills aiming to guarantee universal access to methods and information on birth control and maternal care. The bills have become the center of a contentious national debate. There are presently two bills with the same goals: House Bill No. 4244 or An Act Providing for a Comprehensive Policy on Responsible Parenthood, Reproductive Health, and Population and Development, and For Other Purposes introduced by Albay 1st district Representative Edcel Lagman, and Senate Bill No. 2378 or An Act Providing For a National Policy on Reproductive Health and Population and Development introduced by Senator Miriam Defensor Santiago. While there is general agreement about its provisions on maternal and child health, there is great debate on its key proposal that the Philippine government and the private sector will fund and undertake widespread distribution of family planning devices such as condoms, birth control pills(BCPs) and IUDs, as the government continues to disseminate information on their use through all health care centers. The bill is highly divisive, with experts, academics, religious institutions, and major political figures supporting and opposing it, often criticizing the government and each other in the process. Debates and rallies for and against the bill, with tens of thousand participating, have been happening all over the country. Background The first time the Reproductive Health Bill was proposed was in 1998. During the present 15th Congress, the RH Bills filed are those authored by (1) House Minority Leader Edcel Lagman of Albay, HB 96; (2) Iloilo Rep. -

Philippine Weeklyphilippine Update

Philippine WeeklyPhilippine Update WEEKLY UPDATE WE TELL IT LIKE IT IS VOLUME VI, NO. 19 May 18 - 22, 2015 _______ ___ _ ____ __ ___PHIL. Copyright 2002 _ THE WALLACE BUSINESS FORUM, INC. accepts no liability for the accuracy of the data or for the editorial views contained in this report.__ Political "Quotes VP Binay willing to answer AMLC allegations in court of the Week" The camp of Vice President Jejomar Binay is willing to appear in court and face allegations stemming from the Anti-Money Laundering Council's (AMLC) report. The AMLC earlier published a report listing 242 bank accounts, investments and insurance policies under the “It’s not about politics. It’s about name of Vice Pres. Binay, his family and his friends. Vice Pres. Binay’s camp is set to oppose the application of the rules in the the freeze order of the Court of Appeals over his alleged anomalous bank accounts. His camp Senate.” also maintained that publishing the AMLC report was illegal and should not be used as an instrument for political harassment. According to them, the AMLC report is misleading since Presidential Spokesperson Vice Pres. Binay only owns 5 of the 242 listed bank accounts. Edwin Lacierda on the accusation made by the Vice President’s camp Binay slams LP for arrest of 14 aides that the administration was behind The Senate on Tuesday ordered the arrest and detention within 24 hours of 14 aides and the Senate’s arrest order. business associates of Vice President Jejomar Binay for snubbing hearings into corruption allegations against him. -

Censeisolutions.Com Or Call/Fax +63-2-5311182

Strategic Analysis and Research by the THE CENTER FOR STRATEGY, ENTERPRISE & INTELLIGENCE It is the rising political awareness of our people that we regard as our greatest triumph. … once we get into Parliament we will be able to work towards genuine democratization SEI ~ Nobel Peace laureate Aung San Suu Kyi speaking on Myanmar's parliamentary cen elections after a year of democratic reforms Report Life is tough here. We make just enough to survive. We just hope she can improve our lives ~ Father of four on democracy icon Aung San Suu Kyi's impending election victory Volume 2 - Number 13 • April 2-8, 2012 NATION 4 The Long Struggle to Silence the Guns After half a century of insurgency and counter-insurgency, are the government and the communists and separatists any closer to ending the bloodletting? Here’s a review of the long and winding trail to the elusive peace agreements. • 1968: A year of global revolutionary fervor spurs socialist and Muslim rebels in the Philippines • The ARMM Solution: Making peace in Mindanao under the Republic and the Constitution • Bangsamoro: Will awarding Muslim ancestral domains pacify the MILF? • Reds underground: From Hukabalahap to New People’s Army, the communists took on colonial and Filipino forces 11 Making Mining Serve Nation and Nature The government finds itself between a ton of rocks and a bunch of hard places • Academicians wondering aloud: The Ateneo School of Government asks a host of tough questions that are anything but academic WORLD 20 Now, Say Hello to Generation C Meet the wired and wireless global community of social-networked, BBM-and-SMS- connected, bandwidth-hungry multitaskers who live and love, work and play via their phones, tablets and PCs. -

Focus on the Philippines Yearbook 2010

TRANSITIONS Focus on the Philippines Yearbook 2010 FOCUS ON THE GLOBAL SOUTH Published by the Focus on the Global South-Philippines #19 Maginhawa Street, UP Village, Diliman, Quezon City, Philippines Copyright@2011 By Focus on the Global South-Philippines All rights reserved. The contents of this publication may be reproduced, quoted or used as reference provided that Focus, as publisher, and the writers, will be duly recognized as the proper sources. Focus would appreciate receiving a copy of the text in which contents of this publication have been used or cited. Statistics and other data with acknowledged other sources are not properties of Focus Philippines, and thus permission for their use in other publication should be coordinated with the pertinent owners/offices. Editor Clarissa V. Militante Assistant Editor Carmen Flores-Obanil Lay-out and Design Amy T. Tejada Contributing Writers Walden Bello Jenina Joy Chavez Jerik Cruz Prospero de Vera Herbert Docena Aya Fabros Mary Ann Manahan Clarissa V. Militante Carmen Flores-Obanil Dean Rene Ofreneo Joseph Purruganan Filomeno Sta. Ana Researcher of Economic Data Cess Celestino Photo Contributions Jimmy Domingo Lina Sagaral Reyes Contents ABOUT THE WRITERS OVERVIEW 1 CHAPTER 1: ELECTIONS 15 Is Congress Worth Running for? By Representative Walden Bello 17 Prosecuting GMA as Platform By Jenina Joy Chavez 21 Rating the Candidates: Prosecution as Platform Jenina Joy Chavez 27 Mixed Messages By Aya Fabros 31 Manuel “Bamba” Villar: Advertising his Way to the Presidency By Carmina Flores-Obanil -

Pcdspo-Report-On-Disaster-Response-Unified-Hashtags.Pdf (PDF | 780.63

PCDSPO Report on Standard Hashtags for Disaster Response Standard Hashtags for Disaster Response I. Background The Presidential Communications Development and Strategic Planning Office (PCDSPO) and the Office of the Presidential Spokesperson (PCDSPO-OPS) have used and have promoted the use of unified hashtags to monitor, track, and consolidate information before, during, and after a natural disaster strikes. This report is an overview of this. It concludes with an assessment of the effectiveness of using unified hashtags. The Official Gazette and PCDSPO Twitter accounts are used to coordinate information dissemination, relief, and rescue efforts with netizens, the private media, and concerned agencies of the government (who also operate on Twitter). Personal Twitter accounts of Presidential Spokesperson Edwin Lacierda, Undersecretary Manolo Quezon, and Deputy Presidential Spokesperson Abigail Valte also actively promoted the responsible use of the hashtags. The following are the official Twitter accounts of the Official Gazette and PCDSPO, as well as the officials of the OPS and the PCDSPO who are considered public figures, and who have Twitter handles with large followings: · Official Gazette - @govph · PCDSPO - @pcdspo · Sec. Edwin Lacierda - @dawende · Usec. Manuel L. Quezon III - @mlq3 · Usec. Abigail Valte - @abi_valte II. Origin We recognized that Twitter is a useful platform for disseminating government advisories, esp. to private media organizations, which can disseminate a message across media, social strata, and geographic location with speed and efficiency. Twitter is also useful for collecting information from the ground, especially at times of disaster in places where a relatively large portion of the population is online (i.e., the capital). The hashtags #rescuePH and #reliefPH were first used in August 2012, when the country was experiencing storm-enhanced monsoon rains. -

May 3 , 2013), Dispatch for May 6 , 2013 (Monday), 23 Photonews , 4 Weather Watch, 6 Regl.Watch , 2 OFW Watch , 18 Online News

Aguinaldo Shrine Pagsanjan Falls Taal Lake Antipolo Church Lucban Pahiyas Feast PIA Calabarzon 4 PRs ( May 3 , 2013), Dispatch for May 6 , 2013 (Monday), 23 Photonews , 4 Weather Watch, 6 Regl.Watch , 2 OFW Watch , 18 Online News Weather Watch 3 hours ago near Quezon City, Philippines PAGASA weather forecaster Fernando Cada on DZMM: -Kahapon po sa Metro Manila ay nakapagtala po tayo ng umabot sa 36 degrees Celsius. -Ang pinakamainit po na naitala natin kahapon ay bandang 1:50pm. -Buwan po kasi ng Mayo, usually po may mga thunderstorm sa hapon after nun mawawala rin. -Ang normal po, sa ikalawang linggo ng Mayo hanggang unang linggo ng June ang ating pagsapit ng panahon ng tag-ulan at iyon po ay kasabay din ng ating Habagat. Weather Watch 4 hours ago near Quezon City, Philippines ABS-CBN: Ayon sa PAGASA, hanggang Biyernes pa ng madaling araw maaaring masaksikan ang meteor shower na parte ng kometang Halley. Sa May 10 naman ay masasaksihan ang partial solar eclipse na makikita naman sa southern portion ng bansa. Weather Watch 4 hours ago near Quezon City, Philippines GMA resident weather forecaster Nathaniel Cruz: -Easterlies na lang ang umiiral sa silangang bahagi ng bansa. -Bahagyang huhupa ang pag-ulan kaya sa Luzon ay magiging mainit at maalinsangan ang panahon maliban sa central section hanggang Bicol region. -Sa Metro Manila, may posibilidad ang mahinang pag-ulan na mararanasan lalo na sa hapon o gabi pero mananatili pa rin ang alinsangan na tatagal sa loob ng 5 araw. -Sa Visayas, mainit at maaraw pa rin ang panahon. -

Pmah Holds Is New Dotc

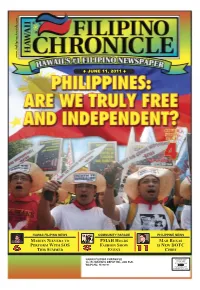

JUNE 11, 2011 HAWAII FILIPINO CHRONICLE 1 ♦ FEBRUARY♦ JUNE 11, 19, 2011 2011 ♦ ♦ HAWAII-FILIPINO NEWS COMMUNITY PARADE PHILIPPINE NEWS MARTIN NIEVERA TO PMAH HOLDS MAR ROXAS PERFORM WITH SOS FASHION SHOW IS NEW DOTC THIS SUMMER EVENT CHIEF HAWAII FILIPINO CHRONICLE PRESORTED STANDARD 94-356 WAIPAHU DEPOT RD., 2ND FLR. U.S. POSTAGE WAIPAHU, HI 96797 PAID HONOLULU, HI PERMIT NO. 9661 2 HAWAII FILIPINO CHRONICLE JUNE 11, 2011 EDITORIAL FROM THE PUBLISHER t just occurred to me that the year is Publisher & Executive Editor Charlie Y. Sonido, M.D. Freedom is Not Exclusive nearly half over. It seems only yes- his week, Filipinos worldwide will celebrate the 113th terday that we were toasting the Publisher & Managing Editor anniversary of the Declaration of Philippine Inde- New Year and making those impos- Chona A. Montesines-Sonido pendence. I sible-to-keep resolutions. While That fateful day in Kawit, Cavite, was an impor- most forget their New Year’s goals, Associate Editors Dennis Galolo a handful of us do manage to follow T tant turning point in the history of the Philippines. It Edwin Quinabo was the first time when Filipinos proclaimed them- through. If that’s you, then we absolutely hate selves a nation, as a people with a purpose and a di- you. All kidding aside, congratulations on your achievements and Creative Designer Junggoi Peralta rection. One can only imagine the bliss of those present when Gen. keep up the good work! Emilio Aguinaldo unfurled the first Three Stars and a Sun, and Speaking of good work, our cover story for this issue was sub- Design Consultant when the Marcha Nacional Filipina — a vibrant, poetic paean ex- mitted by contributing writer Gregory Bren Garcia in time for the Randall Shiroma tolling the valor of Filipinos and declaring love for the Mother- 113th Anniversary of the Philippine Declaration of Independence. -

Sun May 31 11:12:53 2020 SOURCE: Content Downloaded from Heinonline

DATE DOWNLOADED: Sun May 31 11:12:53 2020 SOURCE: Content Downloaded from HeinOnline Citations: Bluebook 20th ed. Antonio G. M. La Vina, Nico Robert R. Martin & Josef Leroi Garcia, High Noon in the Supreme Court: The Poe-Llamanzares Decision and Its Impact on Substantive and Procedural Jurisprudence, 90 Phil. L.J. 218 (2017). ALWD 6th ed. Antonio G. M. La Vina, Nico Robert R. Martin & Josef Leroi Garcia, High Noon in the Supreme Court: The Poe-Llamanzares Decision and Its Impact on Substantive and Procedural Jurisprudence, 90 Phil. L.J. 218 (2017). APA 7th ed. La Vina, A. G., Martin, N. R., & Garcia, J. (2017). High noon in the supreme court: The poe-llamanzares decision and its impact on substantive and procedural jurisprudence. Philippine Law Journal, 90(2), 218-277. Chicago 7th ed. Antonio G. M. La Vina; Nico Robert R. Martin; Josef Leroi Garcia, "High Noon in the Supreme Court: The Poe-Llamanzares Decision and Its Impact on Substantive and Procedural Jurisprudence," Philippine Law Journal 90, no. 2 (January 2017): 218-277 McGill Guide 9th ed. Antonio GM La Vina, Nico Robert R Martin & Josef Leroi Garcia, "High Noon in the Supreme Court: The Poe-Llamanzares Decision and Its Impact on Substantive and Procedural Jurisprudence" (2017) 90:2 Philippine LJ 218. MLA 8th ed. La Vina, Antonio G. M. , et al. "High Noon in the Supreme Court: The Poe-Llamanzares Decision and Its Impact on Substantive and Procedural Jurisprudence." Philippine Law Journal, vol. 90, no. 2, January 2017, p. 218-277. HeinOnline. OSCOLA 4th ed. Antonio G M La Vina and Nico Robert R Martin and Josef Leroi Garcia, 'High Noon in the Supreme Court: The Poe-Llamanzares Decision and Its Impact on Substantive and Procedural Jurisprudence' (2017) 90 Phil LJ 218 -- Your use of this HeinOnline PDF indicates your acceptance of HeinOnline's Terms and Conditions of the license agreement available at https://heinonline.org/HOL/License -- The search text of this PDF is generated from uncorrected OCR text. -

(GPH) and Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF) Peace Negotiations

Young People and their Role in the Government of the Philippines (GPH) and Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF) Peace Negotiations Michael Frank A. Alar* Summary Young people (ranging from ages 21 to 32 when they entered the process) have been playing various roles in the peace negotiations between the Philippine government and the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF) since the process formally started in 1997. They have not only made up the bulk of the secretariat of both Peace Panels providing administrative and technical support, they have also been involved in shaping the content and language of agreements and in providing the necessary informal back channels that reshaped the dynamics and relationships across the negotiating table. Young people’s motivations for joining the process ranged from a sense of duty (religious, familiar, and tribal) owing to their being born into the armed struggle, a desire to contribute and become part of the solution, and to the practical need to engage in gainful employment that would later find deeper meaning. Among the factors that facilitated their participation in the peace process are: inspiration born out of awareness and understanding of the conflict; the institutionalization of the peace process within the government bureaucracy thus providing a natural entry point for young professionals; trust born out of confidence in young people’s abilities, as a function of security especially among the rebels, and in the ability of their peers as young people themselves opened up spaces for other young people to participate; young people’s education, skills and experience; and the energy, dynamism and passion that comes with being young. -

State of the Nation Address of His Excellency Benigno S. Aquino III President of the Philippines to the Congress of the Philippines

State of the Nation Address of His Excellency Benigno S. Aquino III President of the Philippines To the Congress of the Philippines [This is an English translation of the speech delivered at the Session Hall of the House of Representatives, Batasang Pambansa Complex, Quezon City, on July 27, 2015] Thank you, everyone. Please sit down. Before I begin, I would first like to apologize. I wasn’t able to do the traditional processional walk, or shake the hands of those who were going to receive me, as I am not feeling too well right now. Vice President Jejomar Binay; Former Presidents Fidel Valdez Ramos and Joseph Ejercito Estrada; Senate President Franklin Drilon and members of the Senate; Speaker Feliciano Belmonte, Jr. and members of the House of Representatives; Chief Justice Maria Lourdes Sereno and our Justices of the Supreme Court; distinguished members of the diplomatic corps; members of the Cabinet; local government officials; members of the military, police, and other uniformed services; my fellow public servants; and, to my Bosses, my beloved countrymen: Good afternoon to you all. [Applause] This is my sixth SONA. Once again, I face Congress and our countrymen to report on the state of our nation. More than five years have passed since we put a stop to the culture of “wang-wang,” not only in our streets, but in society at large; since we formally took an oath to fight corruption to eradicate poverty; and since the Filipino people, our bosses, learned how to hope once more. My bosses, this is the story of our journey along the Straight Path.