HUMAN MUTUAL SECURITY and VULNERABILITY AN

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Science Fiction in Argentina: Technologies of the Text in A

Revised Pages Science Fiction in Argentina Revised Pages DIGITALCULTUREBOOKS, an imprint of the University of Michigan Press, is dedicated to publishing work in new media studies and the emerging field of digital humanities. Revised Pages Science Fiction in Argentina Technologies of the Text in a Material Multiverse Joanna Page University of Michigan Press Ann Arbor Revised Pages Copyright © 2016 by Joanna Page Some rights reserved This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution- Noncommercial- No Derivative Works 3.0 United States License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, 171 Second Street, Suite 300, San Francisco, California, 94105, USA. Published in the United States of America by the University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America c Printed on acid- free paper 2019 2018 2017 2016 4 3 2 1 A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Names: Page, Joanna, 1974– author. Title: Science fiction in Argentina : technologies of the text in a material multiverse / Joanna Page. Description: Ann Arbor : University of Michigan Press, [2016] | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2015044531| ISBN 9780472073108 (hardback : acid- free paper) | ISBN 9780472053100 (paperback : acid- free paper) | ISBN 9780472121878 (e- book) Subjects: LCSH: Science fiction, Argentine— History and criticism. | Literature and technology— Argentina. | Fantasy fiction, Argentine— History and criticism. | BISAC: LITERARY CRITICISM / Science Fiction & Fantasy. | LITERARY CRITICISM / Caribbean & Latin American. Classification: LCC PQ7707.S34 P34 2016 | DDC 860.9/35882— dc23 LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2015044531 http://dx.doi.org/10.3998/dcbooks.13607062.0001.001 Revised Pages To my brother, who came into this world to disrupt my neat ordering of it, a talent I now admire. -

IHP News 560 : a Clash of Flawed Governance “Models”

IHP news 560 : A clash of flawed governance “models” ( 21 Feb 2020) The weekly International Health Policies (IHP) newsletter is an initiative of the Health Policy unit at the Institute of Tropical Medicine in Antwerp, Belgium. Dear Colleagues, Some terms seem to be a lot less in vogue these days than just a few years ago (like ‘Grand Convergence’ or ‘Cosmopolitan moment’) whereas others are rapidly gaining momentum - say, 'Age of extinction' or ‘The Great Unraveling’. Against an increasingly dire planetary backdrop, the new WHO-UNICEF-Lancet Commission, A future for the world's children? comes not a day too soon, in other words. Let’s hope the SDG agenda gets a much needed shot in the arm “by placing children, aged 0–18 years, at the centre of the SDGs: at the heart of the concept of sustainability and our shared human endeavour.” The report repositions every aspect of child health through the lens of our rapidly changing climate and other existential threats. Which seems damned right. Back in the real world, however, quite a few billionaires still think they can promise to ‘Save the World’ while standing at the same time for a very harsh model of neoliberal globalization and economic system (which includes for them, more often than not, top-notch “tax optimization”). Jeff Bezos is no doubt one of the worst examples of this, but there are a few others as well, well versed in “tactical philantropy”, who think they can just buy the world (and elections). The prospect of a US presidential race between 2 oligarchs makes my stomach turn - and I’m being diplomatic here. -

Sarajevo 1967 ° "' 1 '"

Grondmaster ayme, lefl, explafntnq the qallle 01 d»eu to 80"011, c.nter, and USSR Champion Stein, Byrne later floated SteIn 10 anOfher leuon o"er the board. accountmq tor Sleln's only lou 01 lhe lournamenl, SARAJEVO 1967 I 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 A 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 W L D !: ~~::: :::::::::::::::::::::.:.... .::: :' .' ...: . ~ ~~, ---.-~;.-.::~;--:~;-"~,==~: =~~f. =~"tl =j~~=;~t="ii"'\'----;.~:;:--;"-;-·I - ::- -;:===-;~'----;~'---";:""~=- 10 ~ .4- ~ 3. tknko , If.! Y.i: % 0 I 0 1 1 I ~ I \ _ ;-1 _~'~ ,;--;;-, - \1)-5 x 1h 'h ':-l - '--'' 1 I I 1 'h I 0 I ,';-,,'c-- -:';-_-- 1().5_ °1 '""' 1h x 0 0 n 1 n I ¥, I 1 1 I ,..' .....;:3_ ~ 9Ik.5 ~ h 1 x I,i h ~ 1 n h I I,i 1;.--:1_ _ 5 1 9 9h . ~~ ° "1 h 1 I,i x 0 I 'h 0 1 "':"''-''''7----:-1 t 6" 5'- - 8'7 .6% o o lit liz 1 x 1,1: .., .., 1 "':t I t ¥l -.' , 2 ~ 81.1 f1lh 1 0 0 n 0 If. :< 0 0 1 J I n _ -;-I _ ';--;-6_ ,_ _ ,.. - 11 Duc1n tcin .. .. .... ... n ~ ~ ~ ~ : ~ "~'- : : ~ ~ ~ --,~,,-:~:-~ ----.-~ :: ~! 12. Ja.noS('vic .... ... ... ... .. ~_-;";... _~ ~ _Ifl "1 ;;:0'--;,;..0 _ 0,,-:"':-"''7--;;:''--''''' 1 ~"''-.;.I _ _.;:-' _ ;!i 8 f.. 9 13. Pict%.Sch ................................... \o!t Vr 'tit;. _ ";. ,-~O:- 0 n 'fl 0 0 . __1 'h x 0 1:'.1 0 1 6 --;8- - - 5- 10 14. Bogdanuvic .. .................. Y.t 0 0 0 0 lit Yt 0 0 Yt 1 0 I x 0 h 2 8 5 _ _ " "1.100" :~ : ~:~;:~. -

Collaborative Consumption: Sharing Our Way Towards Sustainability?

COLLABORATIVE CONSUMPTION: SHARING OUR WAY TOWARDS SUSTAINABILITY? by SAMUEL COUTURE-BRIÈRE A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE AND POSTDOCTORAL STUDIES (Political Science) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) December 2014 © Samuel Couture-Brière, 2014 ABSTRACT Collaborative consumption (CC) refers to activities surrounding the sharing, swapping, or trading of goods and services within a collaborative consumption community. First, this MA thesis evaluates the factors contributing to the rapid increase of CC initiatives. These factors include technology, personal economics, environmental concerns, and social interaction. Second, the thesis explores the prospects and limits of CC in terms of sustainability. The most promising prospect is that CC seems to generate social capital and initiate a value shift away from ownership. However, institutional forces promoting growth limit this potential. The thesis concludes that CC itself is not enough to achieve sustainability, and therefore, more political solutions are needed. The paper ends with a critical discussion on the future of our growth-based economic model by suggesting that certain forms of CC could represent the roots of a “post- growth” economy. ii PREFACE This thesis is original, unpublished, independent work by the author, S. Couture-Brière. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT ............................................................................................................................................... -

Re:Imagining Change

WHERE IMAGINATION BUILDS POWER RE:IMAGINING CHANGE How to use story-based strategy to win campaigns, build movements, and change the world by Patrick Reinsborough & Doyle Canning 1ST EDITION Advance Praise for Re:Imagining Change “Re:Imagining Change is a one-of-a-kind essential resource for everyone who is thinking big, challenging the powers-that-be and working hard to make a better world from the ground up. is innovative book provides the tools, analysis, and inspiration to help activists everywhere be more effective, creative and strategic. is handbook is like rocket fuel for your social change imagination.” ~Antonia Juhasz, author of e Tyranny of Oil: e World’s Most Powerful Industry and What We Must Do To Stop It and e Bush Agenda: Invading the World, One Economy at a Time “We are surrounded and shaped by stories every day—sometimes for bet- ter, sometimes for worse. But what Doyle Canning and Patrick Reinsbor- ough point out is a beautiful and powerful truth: that we are all storytellers too. Armed with the right narrative tools, activists can not only open the world’s eyes to injustice, but feed the desire for a better world. Re:Imagining Change is a powerful weapon for a more democratic, creative and hopeful future.” ~Raj Patel, author of Stuffed & Starved and e Value of Nothing: How to Reshape Market Society and Redefine Democracy “Yo Organizers! Stop what you are doing for a couple hours and soak up this book! We know the importance of smart “issue framing.” But Re:Imagining Change will move our organizing further as we connect to the powerful narrative stories and memes of our culture.” ~ Chuck Collins, Institute for Policy Studies, author of e Economic Meltdown Funnies and other books on economic inequality “Politics is as much about who controls meanings as it is about who holds public office and sits in office suites. -

Hypermodern Game of Chess the Hypermodern Game of Chess

The Hypermodern Game of Chess The Hypermodern Game of Chess by Savielly Tartakower Foreword by Hans Ree 2015 Russell Enterprises, Inc. Milford, CT USA 1 The Hypermodern Game of Chess The Hypermodern Game of Chess by Savielly Tartakower © Copyright 2015 Jared Becker ISBN: 978-1-941270-30-1 All Rights Reserved No part of this book maybe used, reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any manner or form whatsoever or by any means, electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the express written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews. Published by: Russell Enterprises, Inc. PO Box 3131 Milford, CT 06460 USA http://www.russell-enterprises.com [email protected] Translated from the German by Jared Becker Editorial Consultant Hannes Langrock Cover design by Janel Norris Printed in the United States of America 2 The Hypermodern Game of Chess Table of Contents Foreword by Hans Ree 5 From the Translator 7 Introduction 8 The Three Phases of A Game 10 Alekhine’s Defense 11 Part I – Open Games Spanish Torture 28 Spanish 35 José Raúl Capablanca 39 The Accumulation of Small Advantages 41 Emanuel Lasker 43 The Canticle of the Combination 52 Spanish with 5...Nxe4 56 Dr. Siegbert Tarrasch and Géza Maróczy as Hypermodernists 65 What constitutes a mistake? 76 Spanish Exchange Variation 80 Steinitz Defense 82 The Doctrine of Weaknesses 90 Spanish Three and Four Knights’ Game 95 A Victory of Methodology 95 Efim Bogoljubow -

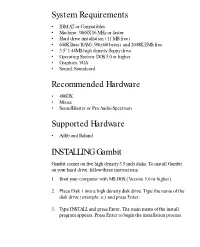

System Requirements Recommended Hardware Supported Hardware

System Requirements • IBM AT or Compatibles • Machine: 386SX 16 MHz or faster • Hard drive installation (11 MB free) • 640K Base RAM (590,000 bytes) and 2048K EMS free • 3.5” 1.44MB high density floppy drive • Operating System: DOS 5.0 or higher • Graphics: VGA • Sound: Soundcard Recommended Hardware • 486DX • Mouse • SoundBlaster or Pro Audio Spectrum Supported Hardware • Adlib and Roland INSTALLING Gambit Gambit comes on five high density 3.5 inch disks. To install Gambit on your hard drive, follow these instructions: 1. Boot your computer with MS-DOS (Version 5.0 or higher). 2. Place Disk 1 into a high density disk drive. Type the name of the disk drive (example: a:) and press Enter. 3. Type INSTALL and press Enter. The main menu of the install program appears. Press Enter to begin the installation process. 4. When Disk 1 has been installed, the program requests Disk 2. Remove Disk 1 from the floppy drive, insert Disk 2, and press Enter. 5. Follow the above process until you have installed all five disks. The Main Menu appears. Select Configure Digital Sound Device from the Main Menu and press Enter. Now choose your sound card by scrolling to it with the highlight bar and pressing Enter. Note: You may have to set the Base Address, IRQ and DMA channel manually by pressing “C” in the Sound Driver Selection menu. After you’ve chosen your card, press Enter. 6. Select Configure Music Sound Device from the Main Menu and press Enter. Now choose your music card by scrolling to it with the highlight bar and pressing Enter. -

Exploring the Hip-Hop Culture Experience in a British Online Community

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2010 Virtual Hood: Exploring The Hip-hop Culture Experience In A British Online Community. Natalia Cherjovsky University of Central Florida Part of the Sociology of Culture Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Doctoral Dissertation (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Cherjovsky, Natalia, "Virtual Hood: Exploring The Hip-hop Culture Experience In A British Online Community." (2010). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 4199. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/4199 VIRTUAL HOOD: EXPLORING THE HIP-HOP CULTURE EXPERIENCE IN A BRITISH ONLINE COMMUNITY by NATALIA CHERJOVSKY B.S. Hunter College, 1999 M.A. Rollins College, 2003 A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of English in the College of Arts and Humanities at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Spring Term 2010 Major Professor: Anthony Grajeda © 2010 Natalia Cherjovsky ii ABSTRACT In this fast-paced, globalized world, certain online sites represent a hybrid personal- public sphere–where like-minded people commune regardless of physical distance, time difference, or lack of synchronicity. Sites that feature chat rooms and forums can offer a deep- rooted sense of community and facilitate the forging of relationships and cultivation of ideologies. -

The Commitments of Bel for Sustainable Development

The commitments of Bel for sustainable development Communications, Public Affairs and Corporate Social Responsibility Direction Editor Laura Mouliade 06/15/2012 Creation date : 06/15/2012 Checker Frédérique Gaulard 06/15/2012 Modification date : - Approving Guillaume Jouët 06/15/2012 Document for internal & external use Communications, Public Affairs and Corporate Social Responsibility Direction POLICY The commitments of Bel for sustainable development Message from the CEO The Bel Group of tomorrow is being built upon our Corporate Social Responsibility Our corporate social responsibility policy lies at the heart of a business model that the Group has adhered to since its creation more than 140 years ago. This is the model of a company driven by the desire to give meaning to its actions, to take into account the interests of its customers, employees and the communities in which it operates. In a time of great economic uncertainty, our increasing sales are a sign of the strong relationships—founded on trust, quality and pleasure—that our brands have forged with their consumers. The Bel Group has undeniable assets for continued growth: the specific nature and strength of our brands and our proximity to our markets are the results of our strategy to internationalize and our Corporate Social Responsibility policy, which guides our actions and ensures our constant growth. Our CSR policy, a commitment that unites Our mission—to bring smiles to all families through the pleasure provided by our products made with dairy goodness—and our values enrich our Corporate Social Responsibility policy. This policy is at the heart of our development strategy and influences all our operations. -

Seduction, Coercion, and an Exploration of Embodied Freedom

SEDUCTION, COERCION, AND AN EXPLORATION OF EMBODIED FREEDOM Jeanne Marie Kusina A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY August 2014 Committee: Donald M. Callen, Advisor Scott C. Martin Graduate Faculty Representative Marvin Belzer Michael P. Bradie © Copyright 2014 Jeanne Marie Kusina All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Donald Callen, Advisor This dissertation addresses how commodification as a seductive practice differs from commodification as a coercive practice, and why the distinction is ethically significant. Although commodification is often linked with technological progress, it has nonetheless been the focus of critiques which assert that many commodification practices can be considered coercive and, as such, are ethically suspect. Markedly less philosophical attention has been devoted to seductive practices which, despite their frequency of occurrence, are often overlooked or considered to be of little ethical concern. The thesis of this essay is that, in regard to commodification, the structural discrepancies between seduction and coercion are such that in widespread practice they yield different degrees of ethical ambiguity and without proper consideration this significant difference can remain undetected or ignored, thus establishing or perpetuating systems of unjust domination and oppression. I argue that a paradigm shift from coercion to seduction has occurred in widespread commodification practices, that seduction is just as worthy of serious ethical consideration as coercion, and that any ethical theory that fails to take seduction into account is lacking a critical element. Drawing on Theodor Adorno’s aesthetic methodology as an approach to working with coercion and seduction within the framework of commodification, I begin by clarifying the main concepts of the argument and what is meant by the use of the term “critical” in this context. -

Great Recession and Us Consumers' Bulimia

GREAT RECESSION AND U.S. CONSUMERS’ BULIMIA: DEEP CAUSES AND POSSIBLE WAYS OUT∗ Stefano Bartolini University of Siena, Italy and CEPS/INSTEAD, Luxembourg Luigi Bonatti University of Trento, Italy Francesco Sarracino CEPS/INSTEAD, Luxembourg May 6, 2012 ∗Luigi Bonatti is grateful to the CEPS/INSTEAD for its generous financial support. He also thanks the CEPS/INSTEAD and the IGS at the University of California Berkeley for their hospitality. We benefited from comments by Giuseppe Di Palma and Andrea Fracasso. Stefano Bartolini is grateful to CEPS/INSTEAD for financial support. The usual disclaimer applies. 1 Abstract This paper attempts to shed light on some aspects of the U.S. consumers’ apparent bulimia that was at the origin of the recent global crisis. We seek to show how different characteristics of the American society and economy, which are usually considered separately, are consistently related to such a multifaceted phenomenon. Hence, we illustrate some structural features of the U.S. economy and public policies that may contribute to create a differ- ence, in terms of patterns of consumption and participation in market activ- ities, between the U.S. and some other advanced economies (in particular, the major economies of continental Europe). We then proceed by presenting some explanations of the U.S. hyper-consumerism. We do so by introducing concepts and analyses elaborated by psychologists and sociologists that may help relating this phenomenon to the decline in subjective well-being and so- cial capital documented in the U.S. over the period preceding the crisis. More- over, we discuss how the NEG (Negative Endogenous Growth) paradigm can account for the recent U.S. -

An Analysis of the Segment Jeanswear

Comunicação e Sociedade, vol. 24, 2013, pp. 251 – 268 The relationship between sustainability and contemporary fashion design: an analysis of the segment jeanswear Mónica Moura e Mariana Dias de Almeida [email protected], [email protected] Faculdade de Arquitetura, Artes e Comunicação, Universidade Estadual Paulista (UNESP) Abstract Fashion is one of the reflexes that best expresses the dynamics of contemporary, and sustainability is one of the questioner agents of the concept and approach of fashion and fash- ion design, this way, the purpose of this paper is to present a critical analysis of the relationship between fashion and sustainability, with the aim of comparing and verifying the discourses of advocated by jeanswear segment companies and the development of its garments, called “sus- tainable”. The reasoning begins from literature review of these areas added to field research with structured interviews, application of questionnaires and later analysis of companies. Keywords Contemporary Fashion; sustainability; jeanswear 1. Introduction Fashion is creation, expression, language, identity; it promotes identity and stream- lines its artistic and cultural production from an economic system that continuously generates objects of consumption for different segments of national and international market. Fashion is in tune and, often, speeds up the time in which we live. “A good ex- ample of this particular experience of time that what we call contemporary is fashion” (Agamben: 2009: 66)1 Fashion goes through many temporal changes, builds new meanings and satisfies social, aesthetic and cultural demands (Simmel, 1971). New shapes that fashion has ac- quired in the last twenty years directly influenced the change of values, and some of these values has demonstrated and acted as questioner agents, such as sustainability.