Chapter 2 Constitutional History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nandita Kathiresan the Forgotten Voices

Nandita Kathiresan The Forgotten Voices in the Fight to Suffrage Political cartoons are unique in the sense that they allocate many interpretations regarding a critical matter based on an individual's outlook of their environment. People of all backgrounds have a special ability to interpret these visuals differently which presents the issue, such as the effects of slavery, in diverse ways as opposed to words on paper. To begin, since the colonization of the United States, slavery was a broad topic that encompassed most, in not all parts of living during the time period. African-American men and women were restricted basic rights up until the end of the Civil War, where they were considered citizens, yet lacked the privilege of suffrage. After the 15th amendment, all men were granted this right, yet women were not presented with such a freedom. Consequently, during the time period of the mid-1800s, women within the country decided to share their voice surrounding the topic of suffrage. The rapidly changing environment in the country gave women the power and strength to fight for this piece of freedom during the Reconstruction Era in numerous marches, such as the Women’s Suffrage Procession. However, it is merely assumed that all women contributed as an equal voice to this important cause, yet black women fell short asserting their voices. This was not due to a lack of passion—rather is the suppression of the freedom of speech covered up by the white, female protesters. Despite living in a country with rapid, positive changes in society, black women were often the forgotten voices fighting for suffrage despite their hidden voice pleading for reform in the late 1800s. -

Coloured’ Schools in Cape Town, South Africa

Constructing Ambiguous Identities: Negotiating Race, Respect, and Social Change in ‘Coloured’ Schools in Cape Town, South Africa Daniel Patrick Hammett Ph.D. The University of Edinburgh 2007 1 Declaration This thesis has been composed by myself from the results of my own work, except where otherwise acknowledged. It has not been submitted in any previous application for a degree. i Abstract South African social relations in the second decade of democracy remain framed by race. Spatial and social lived realities, the continued importance of belonging – to feel part of a community, mean that identifying as ‘coloured’ in South Africa continues to be contested, fluid and often ambiguous. This thesis considers the changing social location of ‘coloured’ teachers through the narratives of former and current teachers and students. Education is used as a site through which to explore the wider social impacts of social and spatial engineering during and subsequent to apartheid. Two key themes are examined in the space of education, those of racial identity and of respect. These are brought together in an interwoven narrative to consider whether or not ‘coloured’ teachers in the post-apartheid period are respected and the historical trajectories leading to the contemporary situation. Two main concerns are addressed. The first considers the question of racial identification to constructions of self-identity. Working with post-colonial theory and notions of mimicry and ambivalence, the relationship between teachers and the identifier ‘coloured’ is shown to be problematic and contested. Second, and connected to teachers’ engagement with racialised identities, is the notion of respect. As with claims to identity and racial categorisation, the concept of respect is considered as mutable and dynamic and rendered with contextually subjective meanings that are often contested and ambivalent. -

Reflections on Apartheid in South Africa: Perspectives and an Outlook for the Future

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 415 168 SO 028 325 AUTHOR Warnsley, Johnnye R. TITLE Reflections on Apartheid in South Africa: Perspectives and an Outlook for the Future. A Curriculum Unit. Fulbright-Hays Summer Seminar Abroad 1996 (South Africa). INSTITUTION Center for International Education (ED), Washington, DC. PUB DATE 1996-00-00 NOTE 77p. PUB TYPE Guides Classroom Teacher (052) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC04 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *African Studies; *Apartheid; Black Studies; Foreign Countries; Global Education; Instructional Materials; Interdisciplinary Approach; Peace; *Racial Discrimination; *Racial Segregation; Secondary Education; Social Studies; Teaching Guides IDENTIFIERS African National Congress; Mandela (Nelson); *South Africa ABSTRACT This curriculum unit is designed for students to achieve a better understanding of the South African society and the numerous changes that have recently, occurred. The four-week unit can be modified to fit existing classroom needs. The nine lessons include: (1) "A Profile of South Africa"; (2) "South African Society"; (3) "Nelson Mandela: The Rivonia Trial Speech"; (4) "African National Congress Struggle for Justice"; (5) "Laws of South Africa"; (6) "The Pass Laws: How They Impacted the Lives of Black South Africans"; (7) "Homelands: A Key Feature of Apartheid"; (8) "Research Project: The Liberation Movement"; and (9)"A Time Line." Students readings, handouts, discussion questions, maps, and bibliography are included. (EH) ******************************************************************************** Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. ******************************************************************************** 00 I- 4.1"Reflections on Apartheid in South Africa: Perspectives and an Outlook for the Future" A Curriculum Unit HERE SHALL watr- ALL 5 HALLENTOEQUALARTiii. 41"It AFiacAPLAYiB(D - Wad Lli -WIr_l clal4 I.4.4i-i PERMISSION TO REPRODUCE AND DISSEMINATE THIS MATERIAL HAS BEEN GRANTED BY (4.)L.ct.0-Aou-S TO THE EDUCATIONAL RESOURCES INFORMATION CENTER (ERIC) Johnnye R. -

Bram Fischer and the Meaning of Integrity Stephen Ellman

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of North Carolina School of Law NORTH CAROLINA JOURNAL OF INTERNATIONAL LAW AND COMMERCIAL REGULATION Volume 26 | Number 3 Article 5 Summer 2001 To Live Outside the Law You Must Be Honest: Bram Fischer and the Meaning of Integrity Stephen Ellman Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.unc.edu/ncilj Recommended Citation Stephen Ellman, To Live Outside the Law You Must Be Honest: Bram Fischer and the Meaning of Integrity, 26 N.C. J. Int'l L. & Com. Reg. 767 (2000). Available at: http://scholarship.law.unc.edu/ncilj/vol26/iss3/5 This Comments is brought to you for free and open access by Carolina Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in North Carolina Journal of International Law and Commercial Regulation by an authorized editor of Carolina Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To Live Outside the Law You Must Be Honest: Bram Fischer and the Meaning of Integrity Cover Page Footnote International Law; Commercial Law; Law This comments is available in North Carolina Journal of International Law and Commercial Regulation: http://scholarship.law.unc.edu/ncilj/vol26/iss3/5 To Live Outside the Law You Must Be Honest: Bram Fischer and the Meaning of Integrity* Stephen Ellmann** Brain Fischer could "charm the birds out of the trees."' He was beloved by many, respected by his colleagues at the bar and even by political enemies.2 He was an expert on gold law and water rights, represented Sir Ernest Oppenheimer, the most prominent capitalist in the land, and was appointed a King's Counsel by the National Party government, which was simultaneously shaping the system of apartheid.' He was also a Communist, who died under sentence of life imprisonment. -

~I~I ~I~ ~I~ Dfa-Aa

Date Printed: 02/05/2009 JTS Box Number: 1FES 52 Tab Number: 10 Document Title: NATIONAL CIVIC REVIEW: THE VOTING RIGHTS ACT AT THIRTY Document Date: 1995 Document Country: USA Document Language: ENG 1FES 1D: EL00754 ~I~I ~I~ ~I~ * 5 6 DFA-AA * WHEN REFORMED LOCAL GOVERNMENT DOESN'T WORK CINCINNATI CITIZENS DEFEND THE SYSTEM .......-VIEW THE C1 ; CONTENTS ________..... V.. OL,.UM __ E.. 84'''' ... NU... M iiiBE_R4 FALL-WINTER 1995 CHRISTOPHER T. GATES THE VOTING RIGHTS ACT Publisher DAVID LAMPE AT THIRTY Editor EDITORIAL BOARD Long considered the most successful civil rights refonn Itgislation o/the 19605, the Voting Rights Act Jaceson CHARLES K. BENS uncertain future as it enters its fourth decade. The principal Restoring Confidence assault involves challenges to outcome-based enforcement of BARRY CHECKOWAY the Act intended to ensure minority representation in addition Healthy Communities to electoral access. DAVID CHRISLIP Community Leadership PERRY DAVIS SYMPOSIUM Economic Development 287 ELECTION SYSTEMS AND WILLIAM R. DODGE REPRESENTATIVE DEMOCRACY Strategic Planning By Joseph F. Zimmerman LEONARD j. DUHL Healthy Communities An overoiewofthe key prouisionsojthe Act and major amendments (1970, 1975 and 1982), with PAUL D. EPSTEIN discussion of landmark judicial opinions and their Government Performance impact on enforcement. SUZANNE PASS Government Performance 310 TENUOUS INTERPRETATION: JOHN GUNYOU SECTIONS 2 AND 5 OF THE Public Finance VOTING RIGHTS ACT HARRYHATRY By Olethia Davis Innovative Service Delivery A discussion of the general pattern of vacilla ROBERTA MILLER tion on the part of the Supreme Court in its interpre Community Leadership tation of the key enforcement provisions of the Act, CARL M. -

Women in Twentieth Century South African Politics

WOMEN IN TWENTIETH CENTURY SOUTH AFRICAN POLITICS: WOMEN IN TWENTIETH CENTURY SOUTH AFRICAN POLITICS: THE FEDERATION OF SOUTH AFRICAN WOMEN, ITS ROOTS, GROWTH AND DECLINE A thesis submitted for the Degree of Master of Arts at the University of Cape Town October 1978 C.J. WALKER ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to express my appreciation to my supervisor, Robin Hallett, and to those friends who helped and encouraged me in numerous different ways. I also wish to acknowledge the financial assistance I received from the following sources, which made the writing of this thesis possible: Human Sciences Research Council Harry Crossley Scholarship Fund H.B. Webb Gijt. Scholarship Fund University of Cape Town Council. The views expressed in this thesis are those of the author alone. CONTENTS List of Abbreviations used in text Introduction CHAPTER 1 : The Position of Women, 1921-1954 CHAPTER 2 : The Roots of the FSAW, 1910-1939 CHAPTER 3 : The Roots of the FSAW, 1939-1954 CHAPTER 4 : The Establishment of the FSAW CHAPTER 5 : The Federation of South African Women, 1954-1963 CHAPTER 6 : The FSAW, 1954-1963: Structure and Strategy CHAPTER 7 : Relationships with the Congress Alliance: The Women's Movement and National Liberation CHAPTER 8 : Conclusion APPENDICES BIBI,!OGRAPHY iv V 1 53 101 165 200 269 320 343 349 354 ABBREVIATIONS USED IN TEXT AAC AllAfricanConvention AME American Methodist Episcopal (Church) ANC African National Congress ANCWL African National Congress Women's League APO African People's Organisation COD CongressofDemocrats CPSA Communist Party -

Stellenbosch and the Muslim Communities, 1896-1966 Stellenbosch En Die Moslem-Gemeenskappe, 1896-1966 ﺳﺘﻠﻴﻨﺒﻮش و اﻟﺠﻤﺎﻋﺎت اﻟﻤﺴﻠﻤﺔ ، 1966-1896 م

Stellenbosch and the Muslim Communities, 1896-1966 Stellenbosch en die Moslem-gemeenskappe, 1896-1966 ﺳﺘﻠﻴﻨﺒﻮش و اﻟﺠﻤﺎﻋﺎت اﻟﻤﺴﻠﻤﺔ ، 1896-1966م. Chet James Paul Fransch ﺷﺎت ﻓﺮاﻧﺴﺶ Thesis presented in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts (History) at the University of Stellenbosch Supervisor: Prof Sandra Scott Swart March 2009 Declaration By submitting this thesis electronically, I declare that the entirety of the work contained therein is my own, original work, that I am the owner of the copyright thereof and that I have not previously, in its entirety or in part, submitted it for obtaining any qualification. Date: 3 March 2009 Copyright © Stellenbosch University All rights reserved i Abstract This study intends to investigate a facet of the race relations of the town of Stellenbosch within the context of state ideology and the reaction of the various local communities towards these policies. Against various internal and external forces, certain alliances were formed but these remained neither static nor constant. The external forces of particular concern within this study are the role of state legislation, Municipal regulations and political activism amongst the elite of the different racial groups. The manner in which the external forces both mould and are moulded by identity and the fluid nature of identifying with certain groups to achieve particular goals will also be investigated. This thesis uses the case study of the Muslim Communities of Stellenbosch to explain the practice of Islam in Stellenbosch, the way in which the religion co-existed within the structure of the town, how the religion influenced and was influenced by context and time and how the practitioners of this particular faith interacted not only amongst themselves but with other “citizens of Stellenbosch”. -

A Teachers Guide to Accompany the Slide Show

A Teachers Guide to Accompany the Slide Show by Kevin Danaher A Teachers Guide to Accompany the Slide Show by Kevin Danaher @ 1982 The Washington Office on Africa Educational Fund Contents Introduction .................................................1 Chapter One The Imprisoned Society: An Overview ..................... 5 South Africa: Land of inequality ............................... 5 1. bantustans ................................................6 2. influx Control ..............................................9 3. Pass Laws .................................................9 4. Government Represskn ....................................8 Chapter Two The Soweto Rebellion and Apartheid Schooling ......... 12 Chapter Three Early History ...............................................15 The Cape Colony: European Settlers Encounter African Societies in the 17th Century ................ 15 The European Conquest of Sotho and Nguni Land ............. 17 The Birth d ANC Opens a New Era ........................... 20 Industrialization. ............................................ 20 Foundations of Apartheid .................................... 21 Chapter Four South Africa Since WurJd War II .......................... 24 Constructing Apcrrtheid ........................... J .......... 25 Thd Afriqn National Congress of South Africa ................. 27 The Freedom Chafler ........................................ 29 The Treason Trid ........................................... 33 The Pan Africanht Congress ................................. 34 The -

AD1844-Bd8-3-3-01-Jpeg.Pdf

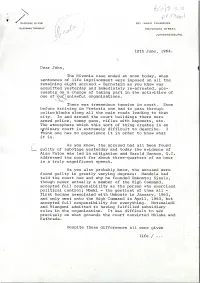

h(d\h 3 . 5 pi 621 INNES CHAMBERS, PRITCHARD STREET, JOHANNESBURG. ,12th June, 1964. Dear John, The Rivonia case ended at noon today, when sentences of life imprisonment were imposed on all the remaining eight accused - Bernstein as you know was acquitted yesterday and immediately re-arrested, pre sumably on a charge of taking part in the activities of one of our"unlawful organizations. 'v- ^ There was tremendous tension in court. Even before arriving in Pretoria one,had to pass through police blocks along all the main roads leading to that city. In and around the court buildings there were armed police, tommy guns, rifles with bayonets, etc. The atmosphere which this sort of thing creates in an cprdinary court is extremely difficult to describe. I tfhink one has to experience it in order to know what it is. /' As you know, the accused had all been found I— guilty of sabotage yesterday and today the evidence of Alan Paton was led in mitigation and Harold Hanson, Q.C. addressed the court for about three-quarters of an hour in a truly magnificent speech. As you also probably know, the accused were found guilty in greatly varying degrees: Mandela had told the court how and why he founded Umkonto; Sisulu, though never actually a member of the High Command, accepted full responsibility as the person who exercised political control; Mbeki - the gentlest of them all - first became associated with Umkonto in January, 1963, and only went onto the High Command in April, 1963, but accepted full responsibility for everything. -

Black Suffrage

BLACK SUFFRAGE: THE CONTINUED STRUGGLE by Danielle Kinney “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal.“ (1) These words, penned by Thomas Jefferson in America's famed Declaration of Independence, are widely known to all, and are thought by many to be at the heart of what it means to be American – to be equals. But in many regards, and speaking in a historical context, this equality has been much more difficult to achieve than it was so simply, and aptly, stated in 1776. Though the issue of equality, or historic lack thereof, can be viewed through the lens of nearly any fundamental and constitutional right, the issue can be seen perhaps at its clearest when applied to suffrage: the right to vote. “One person, one vote“ (2) upon the nation’s founding did not apply to all citizens and was, in fact, a privilege reserved only to the nation’s landholding elite—white, hereditarily wealthy males. Women and the black population, by contrast, had to work tirelessly to achieve this level of equality. While the path to women’s suffrage was without a doubt a struggle, no single demographic faced more of an arduous uphill climb towards that self- evident truth that “all men are created equal“ than America’s black population. From being held in the bondage of slavery, to becoming free yet still unequal, to finally having voting equality constitutionally protected only but a half- century ago, the path to voter equality—and equality in general—has been one met with constant challenge. -

Ida B. Wells, Catherine Impey, and Trans -Atlantic Dimensions of the Nineteenth-Century Anti-Lynching Movement

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by The Research Repository @ WVU (West Virginia University) Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2003 Ida B. Wells, Catherine Impey, and trans -Atlantic dimensions of the nineteenth-century anti-lynching movement Brucella Wiggins Jordan West Virginia University Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Recommended Citation Jordan, Brucella Wiggins, "Ida B. Wells, Catherine Impey, and trans -Atlantic dimensions of the nineteenth- century anti-lynching movement" (2003). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 1845. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/1845 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Ida B. Wells, Catherine Impey, and Trans-Atlantic Dimensions of the Nineteenth Century Anti-Lynching Movement Brucella Wiggins Jordan Dissertation submitted to the Eberly College of Arts and Sciences at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History Amos J. -

Download File

Fisher 1 The Votes of the “Privileged Fair”: Women’s Suffrage in New Jersey, 1776-1807 Louis Fisher Senior Thesis April 2011 Advisor: Professor Emma Winter Second Reader: Professor Evan Haefeli Word Count: 15,608 (20,558 including footnotes) Fisher 2 Acknowledgments The completion of this project represents the capstone of my undergraduate studies, and there are many people who deserve thanks for their contributions and advice. I would first like to thank all of the excellent professors with whom I have had the privilege to study at Columbia. These teachers introduced me to many exciting ideas, challenged me in my development as a student of history, and repeatedly demonstrated why the study of history remains an important intellectual pursuit. I am especially indebted to Professor Emma Winter for her advice and encouragement in seminar, and for reading numerous drafts, followed by helpful and discerning comments each time. Professor Evan Haefeli also provided vital criticisms, which improved both the outcome of this project and my understanding of historical writing. I am also grateful to Mike Neuss for his support and interest in discussing this thesis with me in its earliest stages. My friends and fellow thesis writers also deserve recognition for offering to read drafts and for taking an interest in discussing and challenging my ideas as this project took shape—my friends and colleagues at Columbia have undoubtedly contributed in many ways to my intellectual development over the past four years. Finally, I would like to thank both of my parents and my family for their love and support, and for providing me with the opportunity to pursue all of my academic goals.