Building Inclusive Neighborhoods: Assessing the Socio-Spatial Implications of Transit-Oriented Development in St

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Proof of Payment Ordinance

Proof of Payment Ordinance BOARD OF DIRECTORS MEETING OCTOBER 26, 2017 What is Proof of Payment? 2 Proof of Payment means that passengers must present valid fare media, anywhere in the paid area of the system, upon request by authorized transit personnel. Why Proof of Payment 3 Estimated Revenue Annual Loss: $15M - $25M At least $6M loss supported by data Another $9M - $19M likely Currently, enforcement can only occur at “barrier” locations BPD must directly observe OR Employee or rider must: Witness and be willing to place offender under Citizens Arrest and BPD must be nearby and Offender must be contacted In short, without proof of payment, fare evaders are only concerned at the brief moments when they are sneaking in or out 3 Who Else Uses Proof of Payment? 4 California Other States SMART Dallas Area Rapid Transit Baltimore Light Rail San Francisco MTA Buffalo Metro Rail Santa Clara VTA Charlotte LYNX Cleveland Red Line Heavy Rail Sacramento RTA St. Louis Metro Link Seattle Sounder Commuter Rail and Central Los Angeles MTA Link Light Rail ACE Portland Tri-Met NJ Transit Hudson Bergen & River Lines Caltrain Houston Metro Rail San Diego Trolley Denver RTD Rail Who Uses BOTH Proof of Payment & Station Barriers? 5 SEPTA Philadelphia City Center stations Los Angeles MTA Purple and Red Lines Greater Cleveland RTA Red Line Montreal Metro BC Transit, Vancouver SkyTrain Proof of Payment Protocol 6 Inspections will be fair and non-biased. Police Officers and/or CSO’s will perform inspections within the paid area of the stations and on board non-crowded trains. -

The Bulletin R-42S MAKE THEIR FINAL, FINAL RUN Published by the Electric Railroaders’ Association, Inc

ERA BULLETIN — MARCH, 2020 The Bulletin Electric Railroaders’ Association, Incorporated Vol. 63, No. 3 March, 2020 The Bulletin R-42S MAKE THEIR FINAL, FINAL RUN Published by the Electric Railroaders’ Association, Inc. P. O. Box 3323 Grand Central Station New York, NY 10163 For general inquiries, or Bulletin submissions, contact us at bulletin@erausa. org or on our website at erausa. org/contact Editorial Staff: Jeffrey Erlitz Editor-in-Chief Ronald Yee Tri-State News and Commuter Rail Editor Alexander Ivanoff North American and World News Editor David Ross Production Manager Copyright © 2019 ERA This Month’s Cover Photo: Second Avenue Elevated, looking north from 34th The R-42s are seen at Hammels Wye on the last trip northbound from Far Rockaway-Mott Av to Inwood-207 St. Street in about 1937, pho- Marc A. Hermann photograph tographer unknown. MTA New York City Transit retired the last thusiasts joined MTA Chairman and CEO remaining R-42 subway cars from service Patrick J. Foye and NYC Transit President today, ending a 51-year run. The cars have Andy Byford riding the last R-42 in passen- been used on two dozen lines, each traveling ger service. more than seven million miles. They had a “These cars have served the MTA well as a memorable role in an iconic car-vs.-train reliable fleet over the last 50 years,” said Sal- In This Issue: chase in the classic 1971 film French Con- ly Librera, Senior Vice President, Department LIRR Main Line nection. of Subways for New York City Transit. “As Third-Track The final run followed a send-off ceremony technology advances, we’re looking to mod- at the New York Transit Museum, and was ernize our fleet of subway cars to best serve Project Update scheduled to proceed through a final trip on New Yorkers.” …Page 3 the A line from Euclid Av to Far Rockaway (Continued on page 2) to 207 St, before returning to Euclid Av to close its doors for the last time. -

Syracuse Transit System Analysis

Syracuse Transit System Analysis Prepared For: NYSDOT CENTRO Syracuse Metropolitan Transportation Council January 2014 The I‐81 Challenge Syracuse Transit System Analysis This report has been prepared for the New York State Department of Transportation by: Stantec Consulting Services, Inc. Prudent Engineering In coordination with: Central New York Regional Transportation Authority (CENTRO) Syracuse Metropolitan Transportation Council The I‐81 Challenge Executive Summary of the Syracuse Transit System Analysis I. Introduction The Syracuse Transit System Analysis (STSA) presents a summary of the methodology, evaluation, and recommendations that were developed for the transit system in the Syracuse metropolitan area. The recommendations included in this document will provide a public transit system plan that can be used as a basis for CENTRO to pursue state and federal funding sources for transit improvements. The study has been conducted with funding from the New York State Department of Transportation (NYSDOT) through The I‐81 Challenge study, with coordination from CENTRO, the Syracuse Metropolitan Transportation Council (SMTC), and through public outreach via The I‐81 Challenge public participation plan and Study Advisory Committee (SAC). The recommendations included in this system analysis are based on a combination of technical analyses (alternatives evaluation, regional modeling), public survey of current transit riders and non‐riders/former riders, meetings with key community representatives, and The I‐81 Challenge public workshops. The STSA is intended to serve as a long‐range vision that is consistent with the overall vision of the I‐81 corridor being developed as part of The I‐81 Challenge. The STSA will present a series of short‐term, mid‐term, and long‐ term recommendations detailing how the Syracuse metropolitan area’s transit system could be structured to meet identified needs in a cost‐effective manner. -

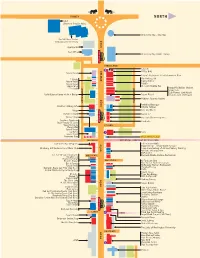

2017 Loop Map Web.Indd

COCA (Center of Creative Arts) University City - City Hall The 560 Music Center of Washington University Apartments Post Office University City Public Library Salon K U-City Grill Future Retail Cicero's Restaurant & Entertainment Plex T-Mobile The Melting Pot Future Retail Jimmy John's Future Retail Público Which Wich St. Louis Bubble Tea L The Vault OOP NOR Randolfi’s Italian Kitchen Seoul Taco Club Fitness (2nd floor) Craft Alliance Center of Art + Design Future Retail Answers.com (3rd floor) TH Midtown Farmers Market PrettiKat Boutique McArthur’s Bakery Cafe Enigma Tattoos Pitaya Sole and Blues Commerce Bank Corner 17 Vintage Vinyl Joy Luck Chinese Express Sunshine Daydream Starbucks Snow Factory St. Louis Vapor Exchange Wong’s Wok Future Retail Taj Mahal Fitz’s Future Retail Shawarma King Chuck Berry Statue CENTENNIAL GREENWAY BICYCLE PATH Side Street Hair Designers Salt + Smoke BBQ Copper Hinge - Small Batch Eyeware Blueberry Hill Restaurant and Music Club Compônere Gallery of Art and Gallery Framing Artisans at Compônere GoMusicSTL Carl Safe Design Consultants Ranoush Middle Eastern Restaurant Doughocracy Avalon Exchange Wizard’s Wagon Al-Tarboush Deli Ben & Jerry's Blue Ocean Sushi Restaurant Future Retail El Maguey Mexican Restaurant Benjamin Evans Law Firm (2nd floor) Phoenix Rising Rocket Fizz Soda Pop & Candy Shop FroYo Create Space DK & Co. Three Dog Bakery Baked T’s OSO: A Style Lab Hats-N-Stuff The Silver Lady Parking Garage H.S.B. Tobacconist Future Retail This! Tivoli Theatre Iron Age Tattoo Fleur de Lou Three Kings Public -

CITIZENS for REGIONAL TRANSIT NEWS Published by Citizens Regional Transit Corporation P.O

CITIZENS for REGIONAL TRANSIT NEWS published by Citizens Regional Transit Corporation P.O. Box 1186, Buffalo, NY 14231-1186 [email protected] http://citizenstransit.org/ Volume #7 Issue # 8 October 2006 Fatal Attraction ‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡ Admit it--an automobile is a beautiful thing. For many of us, the car may be CRTC Monthly Meeting the most beautiful, luxurious item we own. And for many people, their car is an emotional extension of themselves, as well as a cherished pesonal space. To purchase a car is to be attracted to a Tuesday, October 17 vehicle that promises much, including entry into the privilege of job access, 12:00 Noon opportunity for personal solitude on the highway and glimpses of glamour as the night-life crowd cruises the streets. “Eliminating the Theater Station??” But the very vehicle which sates our desires and provides access to many of our needs is fatal to our health. a discussion led by Nationally, car crashes accounted for 43,443 deaths in 2005.* At a rate of 14.6 Chris Hawley per 100,000 population, that’s about 146 fatalities in the Buffalo-Niagara region. Assistant Director, Furthermore, the miles traveled each year Campaign for Greater Buffalo Architecture, History is steadily rising, as is the numbers of vehicles on the road. and Culture Compounded with the effects of air pollution, our fascination with the The Final Design Report for the Preliminary Design of the “Cars Sharing Main automobile truly becomes a fatal Street” project has been posted by the City of Buffalo. In the report, the design attraction. team insists that the Theater Station should be eliminated in order to accommodate cars on Main Street in downtown Buffalo. -

Stone Consulting, Inc. Historic Trolley Projects

Stone Consulting, Inc. Historic Trolley Projects 324 Pennsylvania Avenue West, P. O. Box 306, Warren PA 16365 Phone: 814.726.9870 Fax: 814.726.9855 The Kenosha Transit Electric Streetcar Circulator Harborpark is a new community on the shores of Lake Michigan that would not exist without the streetcar. This redeveloped 69-acre site of a former Nash Engine Plant has approximately 450 new residential units consisting of condominiums, townhouses, garden apartments, and Pike Creek Plaza offers shops, outdoor cafes, and a seasonal farmers’ market Celebration Place is a 12-acre major gathering place Fountain Plaza is a major water feature which serves as Harborpark’s focal point Harborwalk Promenade – an 8’-wide walkway along the water’s edge A mile-long multi-purpose trail with a 7-acre recreational area Added more than $50,000,000 in assessments to the tax rolls A natural history museum was completed in 2001 Stone Consulting, Inc. (Stone) was chosen by the City of Kenosha to provide the prelimi- nary and final design for the track, overhead wire, and the rectifier package for this two-mile historic trolley system connecting the harborfront development with the commuter rail station. The two-mile trolley is an urban connector providing transportation for both tourists and residents. It connects Harborpark to the existing central city area, the METRA commuter rail station, and the city bus transfer station. The presence of the streetcars enhances the character of the area while providing needed mobility and reliability. Kenosha is the first city in Wisconsin to reintroduce an electric trolley system for public transportation. -

Transit Oriented Development Plan for the DELMAR LOOP and FOREST PARK–Debaliviere METROLINK STATIONS

Transit Oriented Development Plan For the DELMAR LOOP and FOREST PARK–DeBALIVIERE METROLINK STATIONS prepared by H3 Studio for the City of Saint Louis Final Report September 2013 Acknowledgements CLIENT GROUP PLANNING TEAM The City of Saint Louis H3 Studio Lead Consultant Honorable Francis G. Slay Mayor Don Roe Director of Planning, Planning & Urban Design John Hoal, Ph.D., AICP Principal-In-Charge Agency Timothy Breihan, A.AIA Major Project Manager Connie Tomasula Urban Designer, Planning & Urban Design Laura L. Lyon, VP, CNU Project Manager Agency Bryan Taylor Robinson, AICP Sustainability Planner Project Manager St. Louis Development Corporation Courtney Cushard, LEED AP Urban Designer Angie Hristova Urban Researcher Otis Williams Executive Director Jonathan Stitelman Urban Designer Amy Lampe Major Project Manager Christopher Liao Technical Staff Reed Miller Technical Staff Andrew Luy Technical Staff TECHNICAL ADVISORY COMMITTEE Bernardin, Lochmueller & Associates Cheryl Adelstein Director of Community Relations & Local Transportation Sub-Consultant Government Affairs, Washington University in St. Louis Douglas Shatto, PE, PTOE Transportation Services Todd Antoine Director for Planning, Manager Great Rivers Greenway District Christopher Beard, PE, PTOE Project Engineer Gary Boehnke Director, Skinker DeBaliviere Community Christopher Joannes Traffic Planner Housing Corporation Ryan Bumb Traffic Engineering Mary Campbell Assistant Vice Chancellor for Real Estate, Specialist Washington University in St. Louis Robert Innis Principal, Kim -

January–June 2003 • $10.00 / Las Vegas Monorail • Transport for London, Part 2

January–June 2003 • $10.00 / Las Vegas Monorail • Transport for London, Part 2: London’s Jubilee Line Extension The Magazine of Electric Railways Published since 1939 by the Electric Railroaders’ Association, Inc. erausa.org/headlights Contents Staff editor and art director January–June 2003 Sandy Campbell Volume 66, Number 1–6 contributors Raymond R. Berger, James N. J. Henwood, John Linden, Raymond J. Mercado, Frank S. Miklos, Chris Slaight and William Vigras COVER STORY Electric Railroaders’ Viva Las Vegas Association, Inc. Raymond R. Berger and Raymond J. Mercado show us how a modest 13 casino shuttle using ex-Disneyworld monorail cars has been transformed E into a world class transportation showcase. Officers & Directors president FEATURE Frank S. Miklos first vice president Charles A. Akins London’s Jubilee Line Extension returns to London with a fascinating photo essay second vice president; corresponding secretary Sandy Campbell 26 Raymond R. Berger of one of the world’s most modern subways. third vice president; recording secretary William K. Guild director Randy Litz treasurer Michael Glikin librarian Richard C. Evans trip & convention chairman Jack May membership secretary Lewis Hitch National Headquarters Grand Central Terminal A-Tower, Room 4A New York City Mailing Address P.O. Box 3323 Grand Central Station New York, N.Y. 10163-3323 Subscriptions 1996 Jubilee Line units stable at Headlights is sent free to members of the ERA. Stratford Market Depot. 26 An application for ERA membership can be found on our website, or we will gladly mail one to you michael pead, wikipedia upon request. Back Issues COLUMNS Back issues of Headlights may be ordered from our website. -

MAKING HISTORY 50 Years of Trimet and Transit in the Portland Region MAKING HISTORY

MAKING HISTORY 50 Years of TriMet and Transit in the Portland Region MAKING HISTORY 50 YEARS OF TRIMET AND TRANSIT IN THE PORTLAND REGION CONTENTS Foreword: 50 Years of Transit Creating Livable Communities . 1 Setting the Stage for Doing Things Differently . 2 Portland, Oregon’s Legacy of Transit . 4 Beginnings ............................................................................4 Twentieth Century .....................................................................6 Transit’s Decline. 8 Bucking National Trends in the Dynamic 1970s . 11 New Institutions for a New Vision .......................................................12 TriMet Is Born .........................................................................14 Shifting Gears .........................................................................17 The Freeway Revolt ....................................................................18 Sidebar: The TriMet and City of Portland Partnership .......................................19 TriMet Turbulence .....................................................................22 Setting a Course . 24 Capital Program ......................................................................25 Sidebar: TriMet Early Years and the Mount Hood Freeway ...................................29 The Banfield Project ...................................................................30 Sidebar: The Transportation Managers Advisory Committee ................................34 Sidebar: Return to Sender ..............................................................36 -

Combined Meeting of the Operations Committee & Audit, Finance And

Combined Meeting of the Operations Committee & Audit, Finance and Administration Committee January 24, 2020 8:30 AM Open Session Agenda Notice of Meeting and Agenda Bi-State Development Combined Operations Committee and Audit, Finance and Administration Committee Meeting Friday, January 24, 2020 at 8:30 a.m. Headquarters - Board Room, 6th Floor One Metropolitan Square, 211 N. Broadway, Suite 650 St. Louis, Missouri 63102 This location is accessible to persons with disabilities. Individuals with disabilities needing information or communication accommodations should call Bi-State Development at (314) 982-1400, for TTY access, call Relay 711. Sign language interpreter services or other accommodations for persons with hearing or speech disabilities will be arranged if a request for such service is made at least two days in advance of the meeting. Large print material, Braille material or other formats will also be provided upon request. Agenda Disposition Presentation 1. Call to Order Approval Chair Holman 2. Roll Call Quorum M. Bennett 3. Public Comment Information Chair Holman 4. Approval of the Minutes of the October18, 2019 Approval Chair Holman Combined Operations and Audit, Finance & Administration Committees, Open Meeting 5. Loop Trolley – Approval of Sustainability Plan and Approval T. Roach / Management Agreement Mokhtee Ahmad, FTA Regional Administrator for Region VII 6. Contract Award – Microtransit Pilot Project Approval J. Mefford-Miller / L. Jackson / J. Gershman 7. Contract Award – Gillig, To Purchase 4 Battery Electric Approval J. Mefford-Miller / Buses L. Jackson / D. Curry 8. Contract Award – Construction of Charging Infrastructure Approval C. Poehler / G. Smith for Battery Electric Buses 9. Contract Award – Transit and MetroLink Station Approval T. -

Date: December 11, 2013 To: Board of Directors From

Date: December 11, 2013 To: Board of Directors From: Neil McFarlane Subject: RESOLUTION 13-12-73 OF THE TRI-COUNTY METROPOLITAN TRANSPORTATION DISTRICT OF OREGON (TRIMET) AUTHORIZING THE TRANSFER OF VINTAGE TROLLEY CARS 511 AND 512 TO THE ST. LOUIS LOOP TROLLEY TRANSPORTATION DEVELOPMENT DISTRICT ___ 1. Issue or Purpose of Item. The purpose of this item is to request that the TriMet Board of Directors (“Board”) authorize the General Manager to execute an agreement with the St. Louis Loop Trolley Transportation Development District (“Loop Trolley”) transferring Vintage Trolley cars 511 and 512 to the Loop Trolley, subject to approval by the Federal Transit Administration (“FTA”). 2. Reason for Board Action. Board authorization for this transfer is required by FTA Circular 5010.1D, Grant Administration Requirements. The attached Resolution authorizing this transfer includes specific content required by Chapter IV, Section 3(l)(7)(b) of FTA Circular 5010.D. 3. Background. In August 2013, Loop Trolley contacted TriMet, expressing interest in using TriMet's Vintage Trolley cars for operation on the new Loop Trolley Project (“Project”), which will bring heritage streetcar service to downtown St. Louis. The Project is scheduled to begin construction in early 2014 and begin operations in mid-2015, and will run 2.2 miles along Delmar Boulevard and DeBaliviere Avenue in downtown St. Louis, with 10 stops, including two connecting with St. Louis MetroLink light rail. The Project has $25 million of FTA grant funding, and a total Project budget of $43 million. Loop Trolley representatives visited TriMet early in September 2013 to assess the suitability of TriMet's Vintage Trolley cars for the Loop Trolley. -

Tip/Stip 2020-2024

2020 – 2024 Transportation Improvement Program (TIP) October 1, 2019 – September 30, 2024 This report was prepared with financial assistance of the U.S. Department of Transportation. However, the contents represent only the view of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the review or approval of the U.S. Department of Transportation. GBNRTC GBNRTC Policy Committee (Policy) Representatives Planning and Coordinating Committee (PCC) Representatives Member Agency Eligible Voting Representative Member Agency Eligible Voting Representative NYSDOT Planning & Program Manager NYSDOT Regional Director NFTA Manager, Grants and Government Affairs Planning & Program Manager Manager, Service Planning NFTA Executive Director Assistant Manager, Grants and Government Affairs Director, Public Transit NYSTA Manger of Permits and Traffic Manager, Grants and Government Affairs Division Director Manager, Service NYSTA Division Director Erie County Commissioner DPW Director of Engineering Erie County County Executive City of Buffalo Acting Commissioner DPW Commissioner DPW City Engineer Director of Engineering City of Buffalo Mayor Niagara County Commissioner DPW Deputy Comm. DPW Commissioner DPW Commissioner Economic Dev. City Engineer Niagara County County Legislature Chair City of Niagara Falls Director of Planning, Environment & Economic Development Senior Project Designer Commissioner Public Works City Engineer City of Niagara Falls Mayor Director of Planning, Environment & Economic Development Senior Project Designer 2020-2024 GBNRTC TIP - Page 2